Fairmount Park Commission

Essay

The Fairmount Park Commission (FPC), constituted by the Pennsylvania state legislature in the Park Acts of 1867 and 1868, administered the city’s public park system from 1867 to 2010. Consisting of six municipal officials or their delegates and ten private citizens appointed by the courts to five-year terms, the FPC had authority to expropriate land throughout the city for recreational use and to protect the municipal watersheds. The commission was semi-autonomous, with its own territories, budget, and (until 1972) police force. The commissioners hired park staff, wrote and enforced regulations, and supervised park improvements and maintenance including the opening of roads, trails and streetcar lines, and the licensing of public transit through park areas.

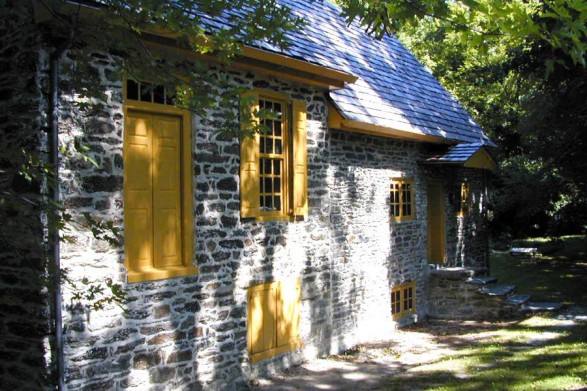

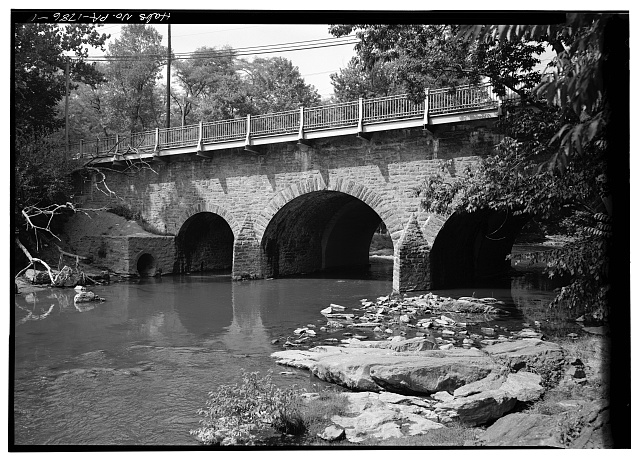

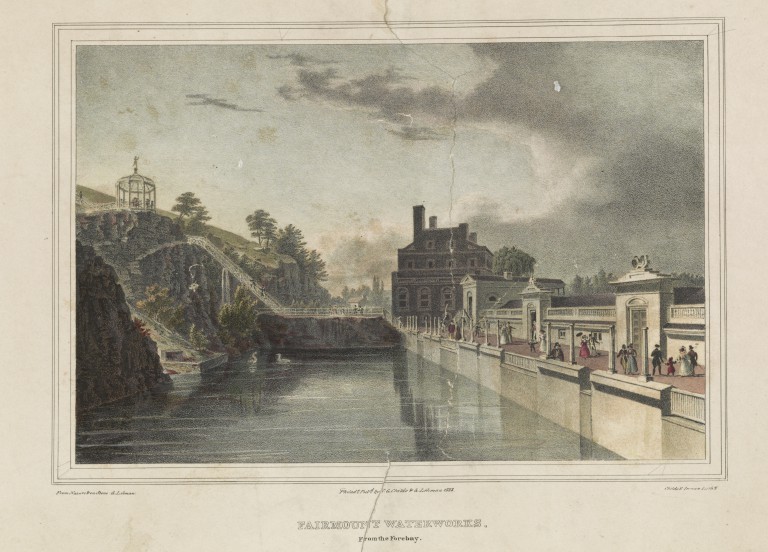

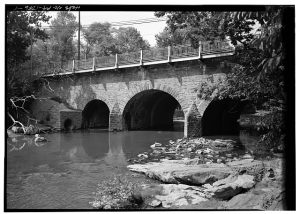

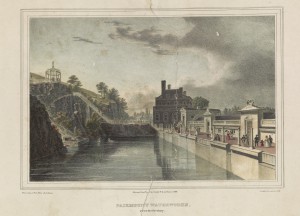

Appointing commissions to implement public works projects was a longstanding practice in England that William Penn (1644-1718) and his associates brought to the colony of Pennsylvania by the beginning of the eighteenth century. Other commissions created in Philadelphia opened streets, managed markets and wharves, ran the gas works, and supervised the construction of city hall. Over the course of its existence, the FPC developed a citywide system of parks and recreation sites, including a network of parks along sections of the Schuylkill and Delaware River watersheds. It also built major roads and parkways, including the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Roosevelt Boulevard, and Cobb’s Creek Parkway and took an active role in administering historic sites and cultural institutions such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Zoo, and the Fairmount Waterworks. At the time of its disestablishment, the FPC managed more than sixty-three parks covering ten percent of Philadelphia’s area or roughly 10,000 acres.

As a result of the FPC’s considerable, albeit ostensibly nonpartisan, authority, appointment to the commission was highly desirable. Although officially appointed to five-year terms, many of commissioners actually served for life. Influential civic and business leaders who served on the FPC included publisher Morton McMichael (1807-79), military commander George Gordon Meade (1815-72), attorney John G. Johnson (1841-1917), investment banker Edward Stotesbury (1849-1938), radio personality Mary Mason, and attorney Robert N. C. Nix III. Multiple generations of the Price and Widener families served on the FPC, including Eli Kirk Price (1797-1884), a founding commissioner, and his grandson Eli Kirk Price Jr. (1860-1933). Industrialist P.A.B. Widener (1834 -1915) served on the commission from 1889 to his death; his great-grandson Fitz Eugene Dixon (1923-2006) was president of the commission from 1983 to 2002.

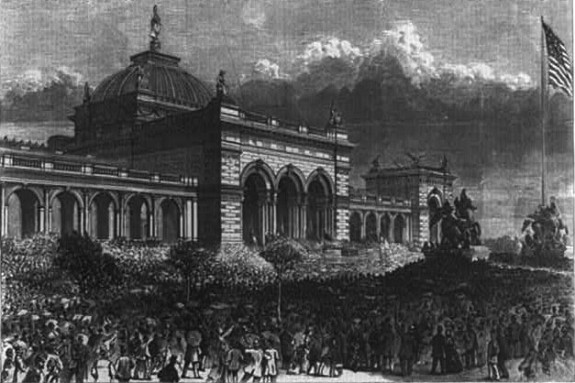

The FPC’s financial history is complex. It had executive power but no authority to collect taxes; most revenue from park operations went to the city’s general fund. On the one hand, the FPC was able to obtain loans as well as gifts of land to pursue an expansionist strategy of park development, adding hundreds of acres to create the citywide system by the mid-twentieth century in an effort to realize William Penn’s vision of a “green country town” and to protect watersheds. On the other hand, unlike many American cities where a percentage of tax income is earmarked for park development and maintenance, the FPC had to request maintenance appropriations annually from city administrations that typically resisted providing more funds to improve or upgrade park landscapes and facilities. In contrast to park administrations in other American cities that operated more transparently as municipal departments, the FPC’s operations became increasingly opaque. Between 1876 and 1899, for example, the FPC issued only one annual report.

Growing concerns among city and state legislators about the FPC’s finances led to a 1937 legislative report that recommended the FPC be abolished. Investigators noted that none of the commissioners were trained in parks management and that important decisions often were made without a quorum because many commissioners failed to attend meetings. As a result, the FPC frequently overpaid for unnecessary land purchases and questionable policy decisions. The report also criticized the FPC for focusing too much on land acquisition and for failing to establish recreational facilities on a par with other American cities. In response, the FPC created a committee on recreation and began to add more recreational facilities, though the outbreak of World War II delayed extensive upgrades.

The FPC affirmed its resiliency when it emerged without change under the new Home Rule Charter enacted in 1951. Although nominally assigned to the reorganized Department of Recreation, the commission continued to operate independently, though its effectiveness had started to weaken. Among notable setbacks was the FPC’s failure to prevent construction of the Schuylkill Expressway through West Fairmount Park. Railroads already traversed many sections of the city’s parklands, and an alternate route farther to the west would have been more expansive and politically difficult because it entailed demolishing residential homes. However, there were some notable successes. During the 1960s, the FPC effectively defeated attempts to build an industrial facility in Fernhill Park and a plan to convert East River (now Kelly) Drive to a limited-access highway. In the 1970s, the FPC secured the cancellation of the Pulaski Expressway (PA 90) project that threatened the Tacony and Pennypack Creek watersheds. During the 1980s, it commissioned comprehensive master plans for the conservation of natural systems in the park system, funded by a grant from the William Penn Foundation.

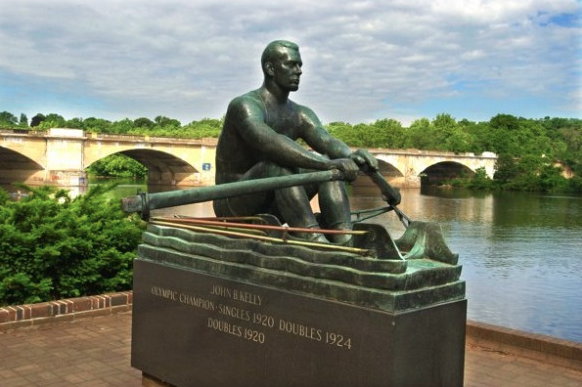

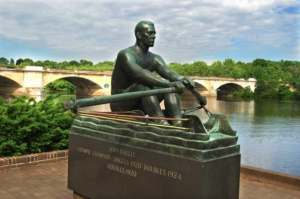

Further efforts by such commissioners as John B. Kelly (1889-1960) and Fredric R. Mann (1903-87) to improve maintenance and recreational programming, and Ernesta Drinker Ballard (1920-2005) who championed natural lands conservation and historic preservation, extended the commission’s legacy. Throughout the FPC’s existence, most commissioners endeavored to fulfill the founding mandate to provide adequate green space and to protect Philadelphia’s water supply. But because the criteria for appointment to the FPC and the actual workings of the commission were unclear, many residents assumed that the city’s parks were adequately managed by well-intentioned stewards who nonetheless were unaccountable to voters. As the city’s tax base diminished with the decline of industry, park appropriations dwindled.

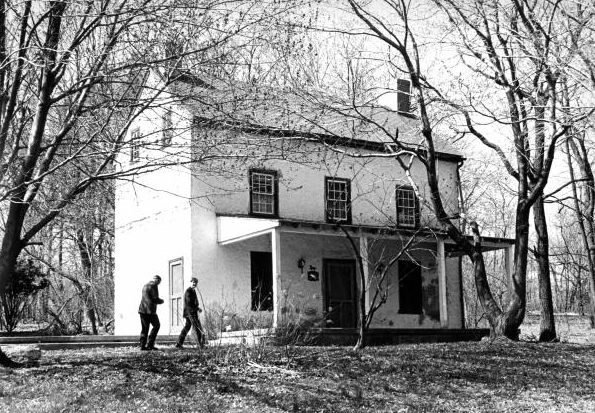

The diminishing effectiveness of the commission was most clearly demonstrated in 2007 when City Council attempted to grant the Fox Chase Cancer Center a long-term lease on a section of Burholme Park in northeast Philadelphia donated to the city in 1896 by Robert Ryerss (1831-96). The majority of commissioners supported the lease because it promised much-needed funding, but this was later nullified when the courts determined that any lease of parkland to a private, commercial entity for nonrecreational use abrogated the public trust doctrine. Pennsylvania’s Commonwealth Court upheld this decision, reiterating that the municipal government has a duty to hold the property “in trust for its originally intended use as parkland.” The decision cost the FPC what remained of its credibility, and in a 2008 referendum Philadelphians voted to disestablish the commission and the Home Rule Charter was duly amended. In the commission’s place, city parks fell under the administration of Philadelphia Parks & Recreation (PPR), led by a commissioner appointed by the mayor, charged with working with an advisory Commission on Parks and Recreation, appointed by City Council to draft and implement policies and standards governing the use of Philadelphia’s parks and recreational facilities.

Elizabeth Milroy is Professor and Department Head of Art & Art History at the Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, Drexel University. She is the author of The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places, 1682-1876 (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Audacious New Plan Unveiled for Fairmount Park (WHYY, May 14, 2014)

- MLK Drive Trail wins $500,000 grant for restoration (WHYY, June 1, 2016)

- Fairmount Park Conservancy launches new guide for enjoying Fairmount Park (WHYY, August 15, 2016)

- Fall construction start for Centennial Commons park ‘porches’ in West Parkside (WHYY, August 16, 2016)