Football (Professional)

By John Maxymuk | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

From the 1950s onward, pro football’s Eagles ruled the sports roost in Philadelphia, having built a dedicated fan base that filled the stadium each week and careened emotionally from each gridiron success and failure. Moreover, fierce play on the field was echoed by unbridled passion in the stands. That did not change even as the fan base drew more from the suburbs and corporate clients watched the game from the comfort of stadium luxury boxes. The Eagles were the local face of a multibillion-dollar industry, but the appeal remained basic and earthbound. With their intense following, the Eagles dominated media attention all year long as the one team most associated with the city. That is a far cry from the early days of football in the region.

The game of American football developed over the last three decades of the nineteenth century at elite colleges throughout the northeastern United States and then at Midwestern schools in the early twentieth century. Locally, the football power was the University of Pennsylvania, which claimed seven national championships in the sport, including six from 1894 to 1908. Penn still plays at venerable Franklin Field, built as a wooden structure in 1895 with a seating capacity of 30,000, which the institution asserts is the oldest continuously-used football stadium in the country. The stadium was rebuilt as a concrete structure in 1922, with seating increased to 78,000 in 1925. Penn remained a national power throughout the first half of the twentieth century and several times led the nation in football attendance. However, attendance for Penn football fell in subsequent years, generally running about 10,000 per game recently, while the professional game flourished.

The roots of pro football are exceedingly humble and date from the 1890s in western Pennsylvania. Postgraduate football in Philadelphia had its beginnings generally with teams representing organizations from other sports, such as two bicycle clubs, the Century Wheelmen and the Park Avenue Wheelmen. The first all-professional team, formed as the Philadelphia Football Club in 1901, was founded by Charles “Blondy” Wallace (1880-1937), a former tackle for Penn. When the Phillies baseball club assumed sponsorship of the team in 1902, Wallace formed his own team representing the rival Athletics baseball team. The addition of a team from Pittsburgh enabled the formation of the first National Football League (NFL). The three teams played a round-robin schedule that allowed both Pittsburgh and the Athletics to claim the league title.

Slow but Steady Growth

That initial NFL disbanded after a single season, but pro football slowly continued to grow, primarily throughout Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the Midwest over the next two decades. In the Philadelphia region, semipro football teams represented local athletic clubs, and the most successful ones were the Union Club and the Frankford Athletic Club.

Formed in 1907, the Union Club assembled a juggernaut independent team in 1920 managed by Leo Conway (1886-1939) that boasted former stars from Penn and Lafayette, several of whom doubled as members of the Buffalo All-Stars of the new American Professional Football Association (renamed the NFL in 1922). Because Pennsylvania blue laws forbade pro sports on Sundays, several players performed for the Unions on Saturday and Buffalo on Sunday, a practice that later was disallowed. After an undefeated 1920 season, the Unions claimed to be the U.S. professional champions. With the Phoenixville club striving to cut costs in 1921, Conway formed a separate team in Philadelphia with most of the same players, and the unaffiliated Union Quakers claimed to be city champions that year.

As the Quakers faded from prominence, the Frankford Yellow Jackets emerged as the local professional power under the sponsorship of the Frankford Athletic Association, founded in 1899 as the sponsor of a variety of sports. The club disappeared within a decade, but some members formed the Loyola Athletic Club in 1909, changing the name back to the Frankford Athletic Association in 1912, and directing all profits to local charities. By 1922, Frankford was the top independent football team in the area with an undefeated record. For $100,000 that year, the club erected the 12,000-seat Frankford Stadium on Dyre Street in northeast Philadelphia. After another successful independent season in 1923, the Yellow Jackets joined the NFL in 1924.

Because of Pennsylvania’s blue laws, Frankford played more games than any other team in the league. Often after a Saturday game, they would travel to the home of that day’s opponent to play again on Sunday to mark two games on one weekend. In other instances, Frankford’s Saturday opponent would travel to nearby Pottsville to play the Maroons on Sunday because the blue laws were not well-enforced in the coal regions. Frankford reached its apex in 1926 by winning the NFL championship with a 14-1-1 record, ensuring sufficient profits to pay for a new coal heater for the Frankford Day Nursery.

Setbacks and Suspension

That year Philadelphia had two football champions when Leo Conway’s reconstituted Philadelphia Quakers won the championship in the short-lived original American Football League. However, Frankford’s determination to rein in expenses resulted in the departure of star player-coach Guy Chamberlin (1894-1967) and the ultimate decline of the team. The mostly-rookie 1930 Yellow Jackets dropped to 4-13-1. The following year the stadium burned down, and the team, rendered insolvent by the Depression, was suspended by the league.

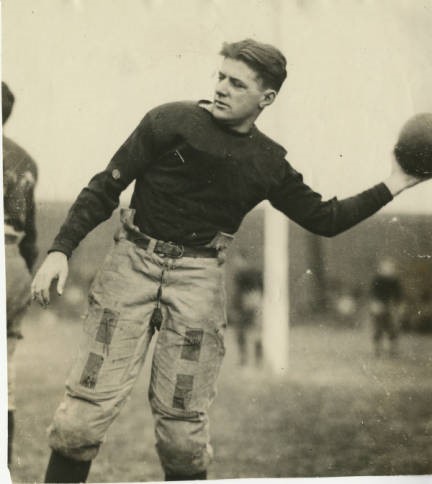

A year later, professional football in Philadelphia found its champion in De Benneville “Bert” Bell (1895-1959). The blue-blooded Philadelphian was the son of the state Attorney General John C. Bell, and his brother John Jr. would serve for a brief time as governor of Pennsylvania. Bell was a colorful character—quarterback of Penn’s 1917 Rose Bowl team and a member of the 1920 Union Quakers—and one who knew how to get things done. Using his connections, he was instrumental in lifting the state’s prohibition of Sunday football. He and lifelong friend and Penn classmate Lud Wray (1894-1967) purchased a new NFL franchise for Philadelphia in 1933 by assuming the debts of the defunct Yellow Jackets. Bell named the team after the symbol of Franklin Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration, the eagle. Wray was the first coach, with Bell filling in all other administrative roles.

For the team’s first decade, attendance was abysmal at 13,680 per game, while the team played at the Phillies’ cramped Baker Bowl (at Broad and Lehigh) through 1935, and in cavernous Municipal Stadium from 1936 to 1939. Despite Bell devising the NFL draft that allowed the poorest teams to go first in choosing college seniors, the Eagles remained a terrible team, going 19-65-3 from 1933 through 1940. Bell tried what he could to interest the public in his team, such as televising team practice to the Franklin Institute in 1934 and recruiting convicted felon Edwin Collins “Alabama” Pitts to play shortly after his release from Sing Sing Prison in 1935, but nothing was successful. Bell even postponed the team’s 1939 home opener due to “threatening weather” on a day baseball’s A’s managed to play a doubleheader.

Following the 1-10 1940 season, Bell and struggling Pittsburgh Steelers’ owner Art Rooney (1901-88) discussed merging their two teams as the Pennsylvania Keystoners. Instead, Rooney sold the Steelers franchise to 28-year-old millionaire playboy Lex Thompson (1911-54) and purchased half of Bell’s Eagles franchise in December 1940. The players of the two teams were reshuffled between the franchises. Then in April 1941, Rooney and Bell moved their franchise to Pittsburgh, and Thompson moved his to Philadelphia, with the Steelers now the Eagles and the Eagles now the Steelers. Thompson, a Yale man, hired Yale assistant coach Alfred “Greasy” Neale (1891-1973) as the Eagles new head coach. Neale was the first NFL coach to copy the Chicago Bears’ new T-formation offense and formulated his own 5-4-2 defensive alignment that became known as the Eagle Defense and was adopted throughout the league.

Eagles + Steelers = Steagles

The Eagles continually improved through the war years, posting their first winning season in 1943, the year the Eagles and Steelers merged to form the Steagles. They played four home games in Philadelphia and two in Pittsburgh that season, while the players also worked in defense plants and lived in boardinghouses. Ultimately, 104 Eagle players as well as owner Thompson served in World War II, with two players dying on French battlefields. After three second-place finishes as the reconstituted Eagles from 1944 to 1946, Philadelphia started a string of three Eastern Division crowns in 1947, winning the NFL title in both 1948 and 1949.

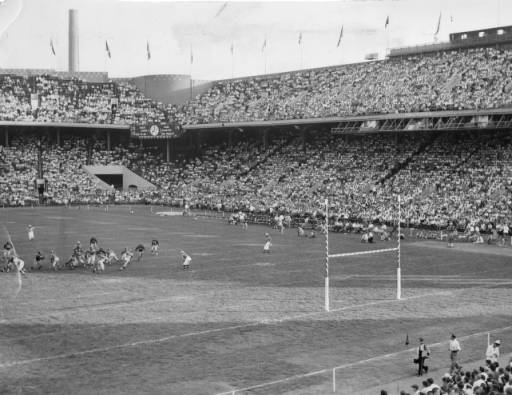

That rough-and-tumble Eagle team mirrored the city’s blue-collar fan base, but with an average home attendance of roughly 25,000 in dismal Shibe Park, the team struggled to make a profit competing for players with the rival All-America Football Conference (AAFC) in the postwar era. In 1949, Thompson sold the team to a consortium of 100 local businessmen dubbed the “100 Brothers.” Opening day of 1950 pitted the two-time NFL champs against Cleveland, the four-time champs from the newly-merged AAFC, to produce the Eagle’s highest attendance of the decade (71,000), but Philadelphia lost 35-10 in the clash that was something of a precedent to today’s Super Bowl.

While the team declined in the 1950s, it maintained a reputation for rough play that has been a staple in both good years and bad. Fights broke out in approximately 20 Eagles games throughout the 1950s, but after an October 1955 Life expose called “Savagery on Sundays,” two Eagle defenders successfully sued the magazine for libel. The decade also finally brought integration to Philadelphia pro sports with African Americans Ralph Goldston (1929-2011) and Don Stevens (1928-2000) joining the team in 1952, a year in which three other NFL teams integrated their rosters. At that point, less than half the teams in major league baseball had integrated—both the Phillies and A’s were still all white—while the Washington Redskins were the only NFL team yet to sign a Black player.

In 1958, the Eagles moved from Connie Mack Stadium (formerly Shibe Park) to Franklin Field and saw immediate attendance gains from moving to a nicer, larger home in a better neighborhood. After a 1960 title run marked by center/linebacker Chuck Bednarik’s (1925-2015) stellar two-way play, the Eagles cemented their bond with their fans—they have sold out almost every game since 1961. Challengers from rival leagues —the World Football League’s Bell in 1974-75 and the USFL’s Stars in 1984-85 —proved no competition to the fans’ devout attachment to the Eagles. Indoor Arena League Football also boasted a Philadelphia representative, the Soul, from 2004 to 2008 and since 2011. While the 2004-08 team averaged close to 16,000 in attendance over five years and won a championship in 2008 before the league disbanded, the resurrected Soul of recent times proved less successful on the field and at the gate.

Succession of Owners

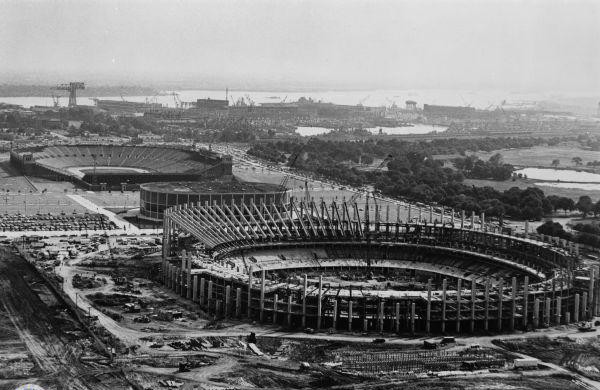

The 100 Brothers, since dwindled to 65, sold the team to construction kingpin Jerry Wolman (1927-2013) in 1963. Ironically, Bert Bell was considering stepping down from being NFL commissioner to repurchase the Eagles for his sons when he died watching the Eagles and Steelers play at Franklin Field in 1959. Both Wolman and subsequent owner Leonard Tose (1915-2003) went bankrupt, ushering in some really bad football (one winning season in 16 years) that encouraged the fans’ belligerent behavior, especially in Veterans Stadium, the publicly financed, multipurpose concrete tomb the team called home from 1971 to 2002. The one highlight there was workaholic coach Dick Vermeil (b. 1936) driving the Eagles to the Super Bowl for the 1980 season.

Locally-born car magnate Norman Braman (b. 1932) bought the team in 1985 and hired as coach boastful Buddy Ryan (b. 1934), who immediately became a fan favorite for his brash mouth and his angry, violent defenses that were notorious for their headhunting but revered in Philadelphia, despite consistently failing in the postseason. Jeffrey Lurie (b. 1951) bought the team in 1995, heading the franchise for the longest and most prosperous period in team history. Until 2018, his biggest achievement was building a new stadium, Lincoln Financial Field, that was largely publicly financed, costing $512 million to construct in 2003. In 2018, though, the Eagles finally ended a 57-year title drought and delivered a championship to Philadelphia by beating the New England Patriots in Super Bowl LII in Minneapolis on February 4, 2018. Four days later hundreds of thousands of fans witnessed a massive celebratory parade from Broad Street to the front of the Art Museum.

Five years later, in 2023 the Eagles returned to the Super Bowl behind a new coach, Nick Sirianni (b. 1981), and quarterback Jalen Hurts (b. 1998) to face the Kansas City Chiefs led by the familiar figure of former Eagles coach Andy Reid (b. 1958) and ace signal caller Patrick Mahomes (b. 1995). In a game noted for being the first championship showdown between two Black quarterbacks as well as the first to feature opposing brothers, Jason Kelce (b. 1987) for Philadelphia and Travis Kelce (b. 1989) for Kansas City, the Chiefs cancelled Philly’s plans for a second parade. Win or lose, the Eagles remained the people’s choice on the city’s ubiquitous sports talk radio stations and the team about which fans dispensed ardent opinions daily, even as local sportswriters and sportscasters devoted to them the most attention of any Philadelphia sports team or activity.

John Maxymuk is a reference librarian at the Paul Robeson Library on the Camden campus of Rutgers University. He is the author of 14 books–10 on football, including Eagles by the Numbers (2005), NFL Head Coaches (2012) and The Quarterback Abstract (2009). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Updated February 12, 2023.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Your brain on football (WHYY, January 20, 2011)

- Eagles star power peps up Germantown High football pep rally (WHYY, November 23, 2011)

- AP Source: NFL plans to change football handling guidelines (WHYY, May 16, 2015)

- Eagles fans meet players at season's first open practice (WHYY, August 5, 2015)

- Some Philly residents aren't happy about extended NFL visit (WHYY, April 7, 2017)

- Big crowds, hometown hero, loud boos give NFL Draft a distinctly Philly feel (WHYY, April 28, 2017)

- Hurts, Eagles clinch playoffs with 48-22 win over Giants (WHYY, December 11, 2022)

- Mahomes, Chiefs beat Eagles 38035 in Super Bowl LVII (Associated Press via WHYY, February 12, 2023)

Links

- Official Site of the Philadelphia Eagles

- Bell Of The Ball: Philadelphia’s Short-Lived Other Football Team (Hidden City)

- The Philadelphia Stars: Philadelphia’s Other Pro Football Team (PhillyHistory.org)

- Veterans Stadium Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory)

- Bert Bell Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory)