High School Sports

Essay

Originating in the nineteenth century, high school sports accompanied the spread of secondary schooling and became a nationwide phenomenon as students initiated team competitions and schools instituted physical education programs. In the Philadelphia region, early scholastic sports gained legitimacy from mentoring provided by the area’s many colleges and from the School District of Philadelphia’s commitment to a comprehensive, exemplary program of physical education. As college attendance became more prevalent, high school and college sports became mutually sustaining and fortified despite the uneven opportunities of secondary schooling in the region.

High school sports emerged at a time when “muscular Christianity”—which aligned physical training and manliness with the development of good morals—justified sport for shaping good habits and character of young men. In that spirit, schoolboys at Philadelphia’s Central High School played baseball in the 1860s modeled after adult clubs and football in the 1870s modeled on college programs. Increasingly, sports became part of high school life in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. High school boys initiated competitive basketball and tennis by the end of the nineteenth century. Contests crossed state lines to include suburban and rural opponents, public and private high schools, non-scholastic organizations, and a mix of secondary and higher educational institutions.

While school leaders sometimes provided playing venues, students managed these nascent sports largely on their own. Student organizers selected high schools for “league” membership in order to crown champions. In 1887, student managers in Philadelphia private high schools organized the Interscholastic Academic League (Inter-Ac), the first in the nation, and area Quaker schools organized a league for Friends’ schools in 1890. Public school boys organized the Philadelphia Public League in 1901. A Southern New Jersey League formed by 1911, and a Camden Suburban League began in 1928. John Bonner (1890-1945), vice-rector of Roman Catholic High School in Philadelphia, guided the creation of the Catholic League in 1919. Eventually, across the region schoolgirls began to compete with the same league opponents as their male counterparts.

Influence of Colleges

In the late nineteenth century, college athletic programs influenced sports for both high school boys and girls. Mimicking colleges, boys formed football squads. They interacted more directly with institutions of higher education in track meets dubbed “Interscholastics.” Swarthmore College, Haverford College, West Chester Normal School, Rutgers College, Princeton University, and Delaware College all sponsored interscholastic track meets for boys. The University of Pennsylvania’s Relay Carnival, a fund-raiser for its Athletic Association, became known as the Middle States Championship and had the longest influence on high school track in the area. At the inaugural relays in 1895, ten colleges and eight public and private high schools sent teams. Into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, high school boys continued to assemble teams to compete at the Penn Relays and similar meets. Penn also hosted a National Swimming Championship for high school boys from 1903 until the early 1920s. Historically Black colleges played a similar role for African American students by opening opportunities for college athletic careers through sponsoring interscholastic track meets and basketball tournaments.

Colleges also offered guidance for athletic associations, referred to as AAs, the organizing backbone of early school sport. From the 1880s to the 1920s, following the example set by colleges, high school students organized sports through AAs. With some administrative support for spaces and permission, AAs managed school sport with student leadership, membership dues, and ticket sales.

For high school girls, the collegiate influence came from teachers who had experienced physical education in their college days and, after 1892, competitive games of basketball. At first, Philadelphia’s secondary school for girls, Girls’ High and Normal School, made space for health reformist ideas. Beginning in 1869, girls had classes in the Dio Lewis System of Gymnastics. During the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, visitors toured the basement of the new Girls’ High building at Seventeenth and Spring Garden Streets that was dedicated in part to gymnastics and touted as a model facility for modern female education. In latter decades, Friends’ schools in the region employed former “YMCA men” as gymnasium instructors for their co-ed students. Philadelphia public schoolboys did not have physical education until 1903, when Pennsylvania mandated its addition to the curriculum.

Basketball, incorporated into high school girls’ compulsory physical education classes, introduced competitive sports. Initially only intraclass games were played, but soon girls across the region seized the chance to play basketball on teams representing their high schools. Interest in volleyball, baseball, track, and tennis followed. Constance Applebee (1873-1981), who introduced field hockey to the United States in 1903, became athletic director at Bryn Mawr College the following year. Her status and influence, including her field hockey summer camp in Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania, for high school girls (1922-94), made the sport prominent in the region.

Colleges also mentored high school sport across the region through the attendance of many college coaches and athletes at year-end high school sports banquets as motivational speakers and honored guests. These collegiate emissaries bestowed prestige along with their advice on skills, practice methods, and programs and encouraged many girls and boys to aspire to play on college teams.

Influence of the Philadelphia School District

In 1907 William Albin Stecher (1858-1950), an activist in nineteenth-century physical culture and editorial board member of the national journal Mind and Body, became the first director of the Philadelphia School District’s newly created Department of Health and Physical Education (DHPE). He instituted a comprehensive, hierarchical, physical education program for elementary to secondary students. The department organized playgrounds, indoor and outdoor meets, and play days for thousands of district students. Capping the program were high school interclass and interscholastic games leading to school and city championships, respectively.

In 1912, the DHPE took major control of sport from students by creating a Supervisory Committee to govern all athletic activities. Similarly across the region, school administrators began to impose eligibility rules based on academic standards and school attendance. From the administrators’ perspective, “playing to win” fit well in the merit-based hierarchy of schooling, but student control did not. The conviction that sport had a place in the curriculum also gained support from the formation of Fathers’ Associations and the awarding of perpetual trophies sponsored at significant expense by the DHPE. Stecher and his successor in 1935, Grover Mueller (1893-1987), a founding member of the American College of Sports Medicine (1954), made Philadelphia a leader in the field of physical education and school sport. Twice, in 1918 and 1932, the school district hosted the national conventions of the American Physical Education Association, which Stecher also cofounded.

As the Philadelphia School District added sixteen high schools between 1908 and 1939, each quickly started girls’ and boys’ sport programs. The district’s commitment to sport had influence beyond its own schools. Outside of Philadelphia, student athletes compared themselves to the larger and older city programs and consistently sought the well-supported Philadelphia teams to fill out their schedules.

At a time when schooling in general aspired to statewide standards, state-level control of athletics emerged amid concern that the teams could be prone to practices incompatible with educational purposes. The Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association (PIAA) formed in 1913, followed by the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association (NJSIAA) in 1918. (Delaware did not have a state organization until 1946.) Together with greater oversight by school administrators, state associations eliminated national championships and competition against non-high school opponents and established state championships instead. NJSIAA sponsored a state championship for football in its first year and the following year for baseball, basketball, and track. The PIAA established most of Pennsylvania’s state championships for boys between 1920 and 1941, adding soccer, football and lacrosse in 1973, 1988 and 2009, respectively. Girls did not compete in state championships until after the federal legislation known as Title IX, which banned discrimination on the basis of sex in any federally-funded activity, changed expectations for girls in sport.

Issues in Girls’ Sport

The earliest contests among schoolgirls, a mix of interclass and interscholastic games, followed the boys’ model but with greater adult supervision to oversee proper demeanor and guard against overexertion. Special girls’ rules reflected cultural concerns about physical exertion and potential overexposure to spectators.

In the feminist milieu of the 1920s, track and field for girls gained impetus from the 1922 “Women’s Olympics” held in Paris. Philadelphia elementary schoolgirls had been competing in running events at district-sponsored field days since around 1903, but inspired by the Women’s Olympics, female students at the seven Philadelphia high schools inaugurated an Interscholastic Track Meet that continued until 1931. From 1921 until at least 1928, Wilmington (Delaware) High School girls ran in a schoolwide track and field meet, and Woodbury, New Jersey, girls started their track team in 1923. Many suburban schools arranged single, dual, and triple meets, and a Delaware County Meet began in 1924.

Just as the girls’ opportunities looked like they would match the boys’, a nationwide effort emerged to eliminate interscholastic sports for high school girls. Women’s physical education professionals saw the increasing publicity and heightened tensions associated with winning competitions as injurious to the players and sought to eliminate the bad effects and expand the good. In 1923, future first lady Lou Henry Hoover (1874-1944), president of Girls Scouts of the USA, first female board member and president of the Women’s Division of the National Amateur Athletic Federation, led a national conference that formulated a new platform for girls’ and women’s sports. In place of interscholastic games, physical educators provided robust intramural programs with point systems for earning the all-important school letter—the same award sought by schoolboy athletes. For decades to follow in cities across the region, intramural programs defined sport opportunities for public high school girls. Philadelphia and some New Jersey high schools developed annual traditions for girls such as “The Annual Demonstration,” the “Gym Contest,” “The Frolic,” and “Sports Night.” These required months of preparation, including the crafting of unique class songs and cheers. For many girls these one-day extravaganzas offered a singular opportunity to demonstrate athletic prowess in front of spectators.

While city public schools purposefully eliminated opportunities for girls to play for spectators and attract media coverage, in Philadelphia’s Catholic High Schools things were quite different. Under the guidance of sport enthusiast John Bonner (1890-1945), interschool competition for girls continued and Catholic girls competed for the Catholic League championship. Philadelphia’s Catholic schoolgirls went to all-girl high schools and reveled in interscholastic basketball games widely supported by classmates, families, school faculty, and administrators. Rivalries developed and gained in importance as generations added to the legacy. In the mid-1940s thousands of spectators filled Convention Hall and later the Palestra—iconic venues for college and professional men’s contests—to watch Catholic schoolgirls in Friday night double-headers play some of the best basketball, college or high school, in the nation. Talented Catholic schoolgirls during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s graduated to collegiate play at the region’s many Catholic colleges and other colleges with strong physical education programs. When national collegiate basketball championships for women began in the late 1960s and 1970s, teams rooted in Catholic schoolgirl basketball were in a position to compete and win, most famously the “Mighty Macs” of Immaculata College.

Although a city school, Delaware’s Howard High School in Wilmington also did not suppress girls’ interscholastic competition. At Howard, the only high school for Black Delawareans, the girls’ basketball team reportedly played “boys’ rules,” not the special “girls rules” devised by professional educators to protect girls from the excesses of sport.

Philadelphia’s numerous suburban communities also continued interscholastic competitions for girls. Country clubs shaped notions of suburban female sportsmanship; competitive athleticism was social competency, not a social concern as it was in the city. While interscholastic competition was eliminated in city schools, suburban and Catholic schoolgirls continued to experience the culture of interscholastic competitions.

Twentieth-Century Transformations

Interest in high school sports expanded after World War II, an era of high birth rates, increasing focus on the family, and expanding suburbanization. New suburban community identities formed around rooting for high school teams, and gendered pageantry accompanied the games. In an era that strictly defined gender roles, cheerleading, once an activity for boys and girls, became female-only. Majorettes and flag girls accompanied the band at football half-time shows. Football teams, once only eleven to twenty players, increased to dozens of students. Students were just the athletes, fully organized, monitored, and coached by school personnel.

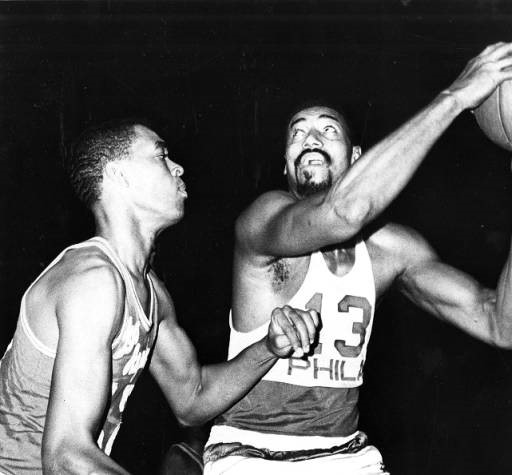

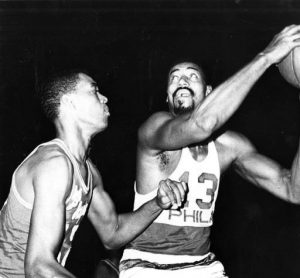

For schoolboys, athletic horizons expanded. A successful high school player could anticipate going on to college and, if successful there, advancing to a professional team. In Philadelphia, Wilt Chamberlain (1936-99), who graduated from Overbook High School in 1953, chose Kansas University from over two hundred offers, leading to his professional career.

After Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), representatives of the all-Black, multistate high school conference, the South Atlantic High School Conference begun in 1929, terminated the conference after awarding its final championships for boys in football, basketball, baseball, cross-country, tennis, track, golf and swimming. Thereafter, Black and white students in Delaware, Virginia, and Maryland competed together.

Philadelphia public schoolgirl interschool competitions slowly reemerged between the late 1940s and the 1960s, but their contests paled in comparison to the robust boys programs that culminated in the Public League and City Championships. The first Philadelphia public school championship for girls in this era took place in the 1969-70 school year for basketball, field hockey, softball, swimming, and tennis. Title IX spurred an expansion in women’s college athletics at a time when more teenage girls were going to college. Consequently, high school sports experience for girls became valuable for admission to college, much as it had for boys since the 1950s. At the state level, Pennsylvania offered the first state championship for girls, in swimming and diving, in 1972. New Jersey schoolgirls played for state championships for the first time in 1973.

While the 1970s expanded athletic opportunity for female high school athletes in metropolitan Philadelphia, “white flight” and other demographic and political changes increased racial segregation in city public schools and sequestered more Black high school athletes in a city league that did not participate in the state athletic association until 2003, and therefore did not compete for state championships. For many decades this was not a concern because in some sports the city championship and the City Title Series (begun in 1938, pitting the best public school boys’ team against the best Catholic school team) carried as much or more prestige than a state title. An indicator of change came when Kobe Bryant (b. 1978) selected suburban Lower Merion High School in 1991 to pursue his athletic aspirations, even though his father had played at Philadelphia’s John Bartram High School, a school with a proud basketball history that included Earl “the Pearl” Monroe (b. 1944) among its graduates.

To give student athletes in Philadelphia access to state championships and their potential impact on college admission, in 2003 the Philadelphia public schools joined the PIAA, and the Catholic schools followed in 2007. Two years later the Philadelphia City Title Series, dormant since a legal challenge to its all-boys policy in 1979, was also revived for both boys’ and girls’ teams. Even the privileged private schools made changes to include post-season laurels. For decades, private and Friends’ schools did not play beyond their regular season schedule, instead basing their league championships on the season’s win-loss records. In 2010 the Pennsylvania Independent Schools Athletic Association formed to provide post-season tournaments. In New Jersey and Delaware both private and public schools joined their state interscholastic athletic associations and competed for state titles.

High school sport in the region’s public, private, and religious schools grew from the deep roots of relationships cultivated by area colleges from the 1880s to the 1920s. By the early decades of the twenty-first century, colleges had long since relinquished their mentorship to local and state school educators. However, sports continued to be entrenched in the education system across the nation. Across gender, race, and religious boundaries, sports made it possible for adolescents in the Philadelphia area not only to compete but also to imagine and experience a relationship with higher education.

Catherine D’Ignazio holds a Ph.D. in Urban Education from Temple University. She is an Adjunct Professor of History at Rutgers University, Camden campus. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- High School Sports Coverage for South Jersey (NJ.com)

- High School Sports Coverage for Philadelphia (Philly.com)

- Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletics Association

- New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletics Association

- Delaware Interscholastic Athletics Association

- Overview of Title IX (U.S. Department of Justice)

- Pennsylvania Sports (ExplorePAHistory.com)