Inner Suburbs

Essay

Presenting a varied and complicated patchwork of both thriving and distressed communities, Philadelphia’s inner suburbs developed during different eras to serve different purposes and populations. European influence predated the Revolutionary War with English, Swedish, Dutch, and Welsh settlers establishing tight-knit farming communities in what were then outlying areas of William Penn’s Philadelphia. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries of slow but steady population increase, stately mansions were built in many of these well-positioned borderland communities as summer homes for wealthy Philadelphians while other communities were setting the foundation to become vibrant industrial towns. Beyond a common penchant toward small-town life and local allegiance, during the twentieth century these communities acquired different identities ranging from upscale hamlets with storied histories of housing wealthy families for more than a century, to working-class towns rooted in manufacturing, to post-World War II suburbs whose middle-class housing began to lose value by the end of the century. These early suburban communities represented a critical juncture in metropolitan dynamics as the first places outside of the city limits to experience rapid population growth during the twentieth century such that their residents were still essentially connected to the urban core while adopting new localized daily routines that began to disconnect them functionally from an urban sensibility.

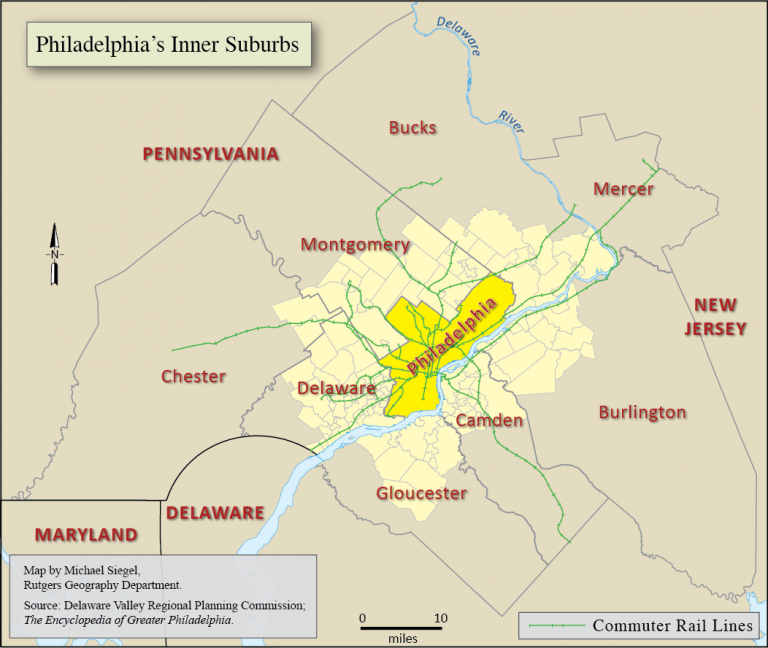

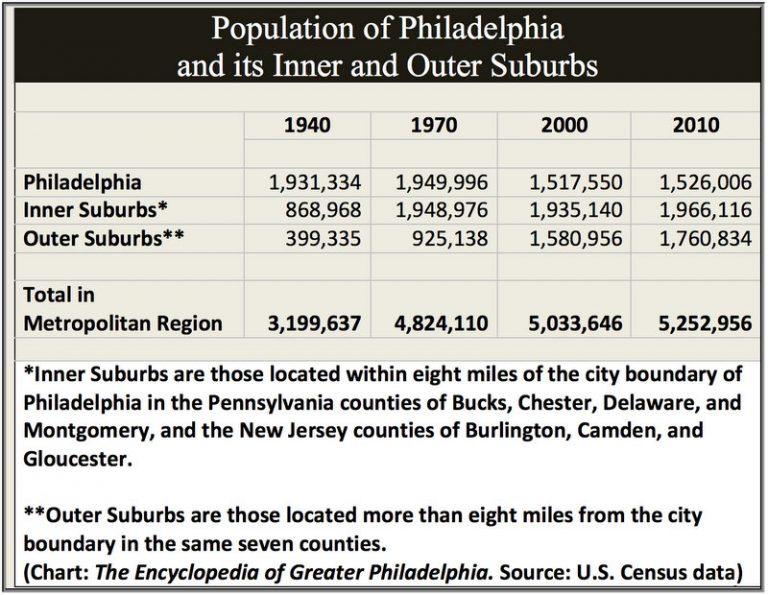

Clustered around the city boundaries, the inner suburbs formed a contiguous ring of older jurisdictions within which the majority of housing dated to 1970 or before. This buffer, extending out approximately eight miles from Philadelphia’s city limits, corresponded roughly to the service area of the region’s popular commuter rail system along which early suburban development coalesced. As such, the region’s inner suburbs could be considered to include the townships, boroughs, and a few cities within eight miles of Philadelphia’s border in Pennsylvania’s Delaware, Chester, Montgomery, and Bucks Counties as well as New Jersey’s Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester Counties. U.S. Census population figures attested to an enduring attraction of inner suburbs to the region’s residents. During the post-World War II era of mass suburbanization, migration flowed mainly to the inner suburbs that grew to be almost equal to the population of Philadelphia by 1970. At the close of the twentieth century, population in the inner suburbs well exceeded that in either the city or the outer suburbs.

During the nineteenth century, many towns along waterways developed as centers of manufacturing in the era of industrialization and became working-class suburbs. Water power and transportation influenced development in places such as Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, where the abundance of creeks and streams allowed for the development of mill towns. Along the Delaware River, Chester, Pennsylvania, became known for its shipyards and factory work in the early 1900s. Paulsboro, New Jersey, home to the Port of Paulsboro, developed its capacity for petroleum transfer and manufacturing. Industrial parks were situated in Pennsauken, on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River. The boroughs of Conshohocken and West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, along the Schuylkill River, became centers for steel and iron production.

Although places that formed this suburban inner ring had unique longstanding histories, the introduction of rail lines in the mid-1800s shaped modern municipal demarcations. One string of affluent inner suburban communities, encompassing parts of Lower Merion and Radnor, Pennsylvania, acquired its moniker as “the Main Line” because the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad ran through these towns. These “bourgeois utopias” with their ample supply of sprawling estates remained prosperous and prestigious areas. In Camden County, New Jersey, a pair of high-income suburbs with lengthy histories similarly retained their appeal for wealthy residents. Haddonfield and Haddon Heights were built as classically laid-out towns with large homes that drew affluent professionals. Railroad connections were integral to the plans of both communities, initially to the Camden and Atlantic Railroad and by 1969 to the PATCO high speed line.

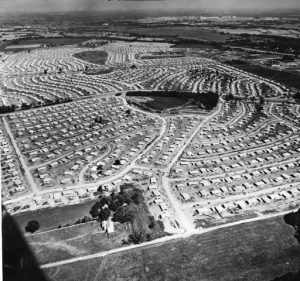

The region’s suburban footprint changed dramatically with the mass suburbanization that defined the post-World War II period. Tract housing subdivisions transformed many of Greater Philadelphia’s inner ring agricultural areas into middle- and working-class bedroom suburbs to mirror the nationwide trend. Levitt and Sons builders chose Greater Philadelphia’s inner suburbs for two of its iconic Levittown communities, one spanning four jurisdictions in Pennsylvania’s Lower Bucks County and the other in Willingboro, New Jersey. Population in the inner suburbs mushroomed. For example, in Lower Moreland, Pennsylvania, a 1940 resident count of 1,451 grew to 11,665 by 1970. In Deptford, New Jersey, a 1940 resident count of 4,738 grew to 24,232 by 1970. With the construction of an extensive network of highways and roads, inner suburbs drew middle- and working-class households seeking the quintessential American dream of owning a single-family home in a neighborhood with good schools, a safe and community-oriented environment, and easy automobile access to anywhere in the metropolitan region. White flight from city neighborhoods fueled the dramatic population increases in the inner suburbs between 1945 and 1970.

After 1970, African Americans began moving into suburbs where a pattern of disinvestment in aging homes had lowered prices enough to make them affordable. Typically, declining housing conditions preceded the arrival of minority buyers, yet many white residents assumed the reverse—namely, that the arrival of minority residents caused housing conditions to deteriorate. In an effort to stem the racial animosity that such transitions prompted, citizens in some racially changing suburbs like Pennsauken, New Jersey, as well as Lansdowne and Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, formed organizations to support minority homebuyers and combat racial discrimination in housing. After 1970, however, some inner suburbs experienced population decline, especially losing white households to outer suburbs and, starting around 2000, to Philadelphia’s downtown. The racial makeup of inner suburbs grew more varied than in outer suburbs whose residents continued to identify predominantly as “white alone” in U.S. Census figures. In a few of the region’s distressed inner suburbs such as Chester and Yeadon, Pennsylvania, racial integration could not be maintained and a process of resegregation into predominantly minority communities ensued by the end of the twentieth century.

Inner suburbs increasingly became a destination of choice for immigrants to the region. By the twenty-first century, immigrant settlement in the inner suburbs followed class divisions as educated professionals chose upper-class enclaves and working-class immigrants gravitated to the more affordable working-class areas with easily accessible public transit. Inner suburbs recorded disproportionate shares of elderly residents, although the trajectory was decidedly upward for both inner and outer suburbs. And poverty began to rise in the inner suburbs, mirroring national trends as well as the trajectory of Philadelphia’s inner city neighborhoods. The public schools in distressed suburbs came to be counted among the worst performing in the region. In under-funded Pennsylvania school districts like William Penn School District, Southeast Delco School District, Norristown Area School District, and Bristol Borough, over 90 percent of fifth graders tested “Not Proficient” on the state’s standardized tests for Math and English in 2021.

A number of factors explained these trends of population decline, demographic change, and increased poverty in Greater Philadelphia’s inner suburbs as well as under-performing schools in certain places. Outdated post-World War II housing stocks and aging infrastructure made many older suburbs less appealing to homebuyers. The regional tide of deindustrialization undermined working-class manufacturing suburbs. In addition, the region’s governmental fragmentation, assigning each suburb responsibility for taxation and service delivery within its boundaries, played a role as small suburban jurisdictions struggled to fund services on a stagnating tax base. The most threatened were bedroom communities that lacked commercial property to bolster tax revenues. For example, the William Penn School District was created in 1972 to serve six small boroughs clustered together near Delaware County’s border with Philadelphia. All were residential communities with little commercial tax base, so the full weight of paying for local services and schools fell on homeowners. Thus inequalities widened among inner suburbs as prosperous communities strategized effectively to strengthen their amenities and advantages with a focus on commercial and office park development as well as educational and medical infrastructure, leaving more vulnerable places to decline. Struggling inner suburbs were thus caught in a “policy blind spot,” overlooked in policy debates that contrasted flourishing outer suburbs with declining cities.

Even as some inner suburbs declined, however, others possessed qualities that positioned them to prosper. Many smaller boroughs offered the charm, walkability, sense of community, and main street orientation that the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission touted in its promotional campaign for the region’s treasured “Classic Towns.” Boroughs such as Narberth and Media in Pennsylvania, and Collingswood in New Jersey, began drawing people to their independently owned main street shops and restaurants as well as their robust community life centered on festivals and public events. Conshohocken successfully capitalized upon its traditional town layout to reinvent itself as a major hub of the region’s knowledge economy. The ample inventory of older housing built before 1939 offered stately and unique architectural features increasingly of interest to homebuyers.

The Philadelphia region’s densely settled inner suburbs exhibited far greater variation than its outer suburbs. In this complicated metropolitan mosaic, pockets of distressed places developed side-by-side with prospering ones. But all shared the continuing geographic advantage of easy access to central Philadelphia in an era when sprawled development patterns shifted growing numbers of suburban residents farther away from, and less able to sustain, connections with the region’s core.

Suzanne Lashner Dayanim holds a Ph.D. in Geography and Urban Studies from Temple University. Her dissertation measured the value of community facilities to inner ring suburban resilience. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Hybrid supermarket-pantry to rise in Chester 'food desert' (WHYY, November 15, 2011)

- How are New Jersey public schools doing? Depends on where you live (WHYY, March 9, 2012)

- Paulsboro residents getting help but not always answers (WHYY, December 5, 2012)

- Can Act 47 finally fix tiny Colwyn's big problems? (WHYY, December 16, 2015)

- Pitching plan for education funding, Wolf visits Upper Darby school (WHYY, May 21, 2015)

- The cold realities of education in a poor Pennsylvania school district (WHYY, April 24, 2016)

- More than 15 years in the making, Port of Paulsboro receives its first shipment (WHYY, March 3, 2017)

- Chesco residents urge officials to reject development plan for contaminated site (NewsWorks, April 25, 2017)

Links

- Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Levittown PA: Building the American Dream (State Museum of Pennsylvania)

- Chester, Pennsylvania : A History of its Industrial Progress and Advantages for Large Manufactures (Archive.org)

- Media Historical Society

- West Philadelphia: A Suburb in a City (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Powelton Avenue: The First Stop on the Main Line? (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Classic Towns of Greater Philadelphia

- Philly Gets Richer, its Suburbs Get Poorer, and the Middle Class… Vanishes? (Philadelphia Magazine)

- Rocking the Suburbs: How the City’s Boom Will Create Regional Balance (Technical.ly Philly)