Delaware River

By Carolyn T. Adams | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

For centuries the Delaware River supplied its region with water, food, transportation, and water power to run mills to saw timber and produce grain, paper, and textiles. As the largest undammed river in the United States east of the Mississippi, its bounty seemed limitless. William Penn (1644-1718) recognized its value when he located his port city of Philadelphia on its banks in a place that would give European settlers access to the Atlantic Ocean and enable trade with Europe and the Caribbean. Unfortunately, like many environmental assets held in common, the river’s resources eventually suffered from overuse by the population along its banks. So great was the strain on this natural resource that in the mid-twentieth century political leaders launched new regional institutions to clean the river and coordinate water usage by the many jurisdictions along its banks.

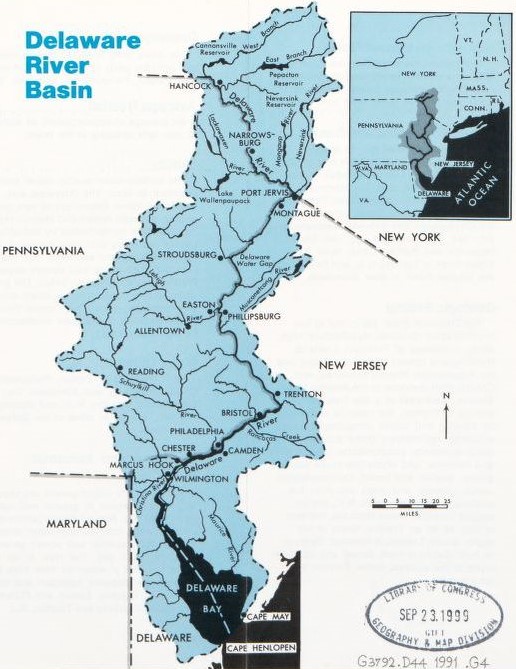

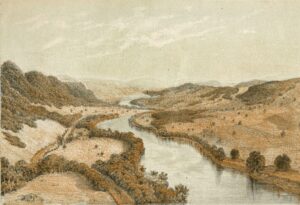

Issuing from two neighboring locations in the Catskills region of New York state, the Delaware flows for 330 miles to the Atlantic Ocean. The West Branch of the river starts in the town of Jefferson southwest of Albany, New York, while the East Branch springs from a small pond nearby in the village of Grand Gorge. Those two headwaters join together to flow southward, picking up additional water from tributaries, including the Lehigh River, the Schuylkill River, and the Brandywine Creek, before finally emptying into the Delaware Bay.

The river’s massive watershed—covering 13,539 square miles of territory within the states of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware—was once the homeland of the Lenape, who based their collective identity as a people on the fact that they all fished in its waters, drank from its feeder streams, and relied on its currents to transport their canoes over long distances. They called it “Lenape Wihittuck,” meaning the rapid stream of the Lenape. So closely did the early Europeans identify the indigenous people with the great river that, once they had renamed the river for the English Lord De La Warr (1577-1618) in the mid-1600s, the newcomers began referring to the native inhabitants as the Delaware people.

Henry Hudson Arrives

Among the first Europeans to encounter the Lenape, the English navigator Henry Hudson (c. 1565-c. 1611) arrived at Delaware Bay while sailing up the coast of North America for the Dutch. In 1640 the Dutch established their first trading post at Fort Nassau (near present-day Gloucester City, New Jersey), exchanging Dutch cloth and goods for beaver pelts.

When in 1682 the English Quaker William Penn arrived with his charter from Charles II (1630-85), making him sole proprietor of the colonial territory, he deliberately sited his commercial center of Philadelphia where it could serve the needs of settlements up and down the river, but also connect the colony to more distant markets. Early settlers quickly began to produce commodities, not just to support their own needs, but also for export.

They built ferries across the river to enable easy travel over large stretches of the province. The Quaker village of Bristol was established in 1697 as a market town for Bucks County farmers. The ferry there took passengers from the Pennsylvania side to Burlington, New Jersey. Eventually, Bristol grew into an important commercial and ship-building center. Farther north on the New Jersey side of the river, the town of Lambertville began as the site where in 1733 Coryell’s Ferry connected New Jersey travelers to the Pennsylvania village of New Hope. Lambertville gradually developed across the centuries into a manufacturing center for paper, rubber, spokes, and wheels.

Undoubtedly, the most famous crossing was George Washington‘s (1732-99) daring decision to transport his troops across the river at McConkey’s Ferry on Christmas night 1776 and lead them to a successful surprise attack against the Hessian troops quartered at Trenton, New Jersey, the morning of December 26.

(Photograph by R. Kennedy for Visit Philadelphia)

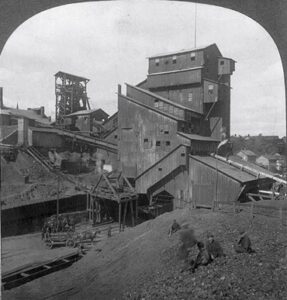

The River Underpins Industrialization

The creeks that fed into the Delaware River spawned some of the earliest water-powered mills in the area. Where the city of Trenton now stands, a gristmill was built in 1679 to process the grain produced by local farmers. Once milled, the grain was sent downriver to Philadelphia for export. In the eighteenth century iron mills and forges sprang up along the river, and by 1760 there was a thriving colonial iron industry that exploited the ore, wood, and water power found there. By the 1840s, sawmills were located at most of the major tributaries in the upper Delaware River Valley, rafting their lumber down the river.

To transport other commodities from the Upper Delaware, however, producers needed more than the swift flow of the river. Riverboats, barges, and rafts carrying lumber, produce, and other commodities to market had to make their way through a succession of rapids, falls, and shallows impassable during large parts of the year. The steep waterfall located at Trenton discouraged large boats from traveling from the Upper Delaware all the way south to Philadelphia.

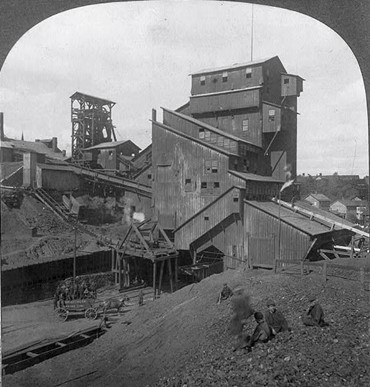

The pressure to overcome these obstructions increased dramatically with the discovery of valuable anthracite coal in northeastern Pennsylvania. That motivated the Pennsylvania legislature to build a canal alongside the Delaware River. By 1830 anthracite coal mined in northeastern Pennsylvania was gaining a growing market in Philadelphia because it burned hotter than other coals in factory furnaces. To connect the coalfields of northern Pennsylvania to urban manufacturers, builders completed the Delaware Division of the Pennsylvania Canal in 1832. That sixty-mile-long Delaware Canal ran from Bristol in lower Bucks County all the way north to Easton, along the right bank of the Delaware River, connecting at its north end to the Lehigh Canal and opening the anthracite coalfields to markets in Philadelphia. In fact, anthracite made up more than 90 percent of the Delaware Canal’s cargo.

(Library of Congress)

Early mills and lumberyards coexisted with abundant fish populations. During the colonial period, the river and bay boasted more than three hundred species of fish including catfish, lamprey, eel, trout, smelt, perch, and pike. Sturgeon and shad figured especially prominently in the diets of the colonists. For example, the shad was said to have saved George Washington’s troops from starvation. At the river’s southern extreme, Delaware Bay spawned a legendary oyster industry, which prospered until the end of the nineteenth century when harvests started shrinking. None of these aquatic populations remained as plentiful once the river became industrialized.

Railroads Arrive

Railroads gained popularity in the mid-1800s, reducing the waterway’s value for transporting goods and travelers. But at the same time, railroads enlarged the market area for the manufacturing plants that lined its banks. Gradually the stretch of river from Trenton south to the Delaware Bay became one of the most highly industrialized regions of the United States, producing textiles, rubber and leather goods, ships, railroad equipment, and steel. Early manufacturers clustered along the shore in industrial villages like Frankford, Kensington, and Bridesburg. In the 1870s Henry Disston developed the entire Tacony neighborhood surrounding his northeast Philadelphia saw works. In Camden, prior to the Civil War, factory owners built housing for workers close to their waterfront mills, sawmills, lumberyards, and railroad companies.

The industrial neighborhood of Frankford in Philadelphia offered a good example of the river’s role in Philadelphia’s industrial development. In the 1660s, Swedes built a gristmill on the northeast bank of Frankford Creek. Then in the early nineteenth century larger factories began to appear in Frankford, attracting more workers, which in turn led to the building of more housing, shops, and services. Like the majority of the factories in the rest of the city, many of those plants produced textiles. In the period just before World War I, Frankford boasted over 150 mills.

Many locations along the river developed industrial specialties. In 1848 German immigrant John Roebling (1806-69) built a plant in Trenton making wire rope that became one of New Jersey’s famed factories, building suspension bridges that included the Brooklyn Bridge. By 1904, when the business needed a larger site with access to the water, it built a new facility on the river at Kinkora, some ten miles from the Trenton plant. Bridesburg spawned a concentration of chemical companies during the Civil War that later became serious polluters.

Major shipyards along the Delaware River included the Cramp Yard in Kensington, the New York Shipbuilding Yard in Camden, and the Sun Shipyard in Chester. Other manufacturers on its banks included oil refineries, food-processing companies, and sugar refineries. In Wilmington, the DuPont Company chose to locate its heavily polluting Chambers Works in New Jersey across the Delaware River from Wilmington. There they produced dyes, petroleum chemicals, Freon, and other substances. Many of these companies chose the river location because it could supply large quantities of water used in production or to dispose of effluents easily and cheaply.

Recreation on the River

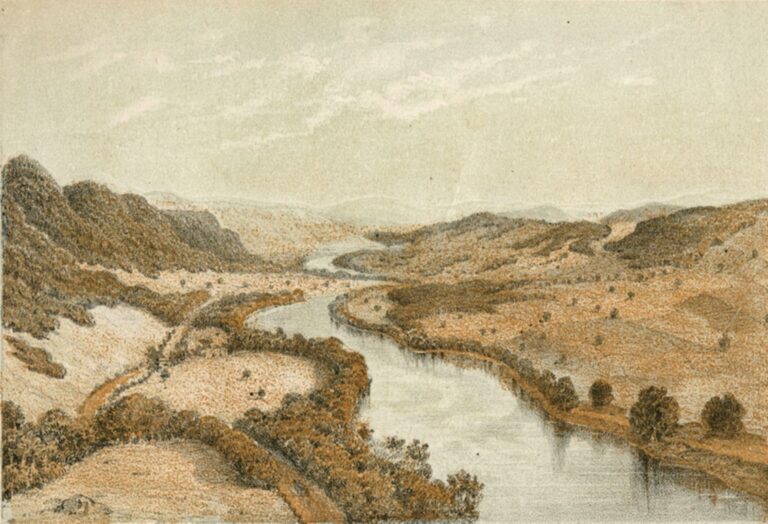

The coming of railroads served not only to transport goods, but also passengers, including some who rode the rails to enjoy the scenic beauty of the Delaware Water Gap, a notch that the Delaware River cut into the Kittatinny mountain ridge about seventy-five miles west of New York City. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, the Delaware Water Gap became one of the most popular summer resorts in the eastern United States. In 1856 the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railways opened a line from New York City when only one hotel served the water gap. Soon a dozen more hotels served visitors who came to enjoy the scenery, hiking, rafting and boating.

(Library Company of Philadelphia)

Closer to Philadelphia the river spawned an entirely different kind of recreation at the turn of the twentieth century when trolley companies invested in amusement parks as a way to increase their weekend traffic. The Delaware River became a favored spot for the popular new pastime, attracting many city dwellers. In Gloucester County, New Jersey, Lincoln Park opened in 1890, followed by Washington Park in 1895. For several decades, both attracted thousands of visitors. In Salem County, Riverview Beach Park opened in 1891 with picnic tables, a dance hall, carousel, and eventually a Ferris wheel; here, most visitors from Philadelphia and Wilmington came by river. In Burlington County, the owner of land on Burlington Island built a pier, pavilion, bathhouse for swimmers, and ice cream stand in 1900. This became the Island Beach Amusement Park whose roller coaster, “the Greyhound,” proved to be its most popular attraction.

Another popular recreation spot, the seventy-mile stretch of the Delaware and Raritan Canal, became a state park in 1974—a recreational corridor for canoeing, jogging, hiking, bicycling, fishing, and horseback riding. Built in the 1830s to connect the Delaware and Raritan Rivers in order to transport coal from Pennsylvania to New York City, the canal towpath ran from New Brunswick to Trenton; a canal towpath/rail trail from Trenton to Bull’s Island; and a rail trail from Bull’s Island to Frenchtown. Its wooden bridges and historic remnants of locks make this walkway an attraction for history lovers.

Environmental Degradation

From colonial days, run-off from tanneries and slaughterhouses contaminated the river. Down through several centuries, increasing numbers of people and enterprises along the river used it as a public sewer to carry untreated waste from their properties. With the growth of manufacturing, the danger to the river increased markedly. Sewers that mixed together stormwater and sewage in a single pipe emptied directly into the river, dumping industrial wastes. Waterborne diseases, particularly cholera and typhoid fever, sickened thousands of Philadelphians during the years between the Civil War and the beginning of the twentieth century. Especially deadly outbreaks of those diseases during the 1890s forced the city to open the Torresdale sand filtration plant in 1908 as a way to clean water taken from the Delaware. By 1912 the city was chlorinating all city water.

Despite such measures to treat the water taken out of the Delaware, the river itself remained an open sewer, filled with industrial and human wastes. In the early 1900s, Philadelphia’s sewers were dumping more than two hundred thousand tons of solids into the Delaware each year. A 1934 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer complained that the few remaining shad found in the river tasted like petroleum.

In 1948, Congress passed the federal Water Pollution Control Act making federal dollars available for river cleanup. That helped Philadelphia to construct three primary sewage treatment plants, the last of which was completed by 1953. Those plants removed solids from the city’s sewage going into the river, but did not eliminate the waterborne bacteria that continued to consume all the available oxygen, depriving fish of the oxygen they needed to thrive in the Delaware. Suburban growth during the 1950s and 1960s in popular riverside locations like the Levittown housing development and the nearby U.S. Steel Plant at Fairless Hills added to the load carried by the Delaware.

The largest water users were power plants. Other large water-using industries were steel, petroleum, chemicals, and paper. More water was used for cooling than for all other industrial purposes. And since warm water contains less dissolved oxygen than cooler water, fish and other aquatic life were suffering from rising water temperatures in addition to contaminants in the river water. Although the river’s defenders tried to mount clean-water campaigns in the early 1920s and late 1930s, industrial lobbyists resisted those efforts.

Managing Spillover Effects

Disputes arose when the actions taken in one state affected the citizens and enterprises located in other states. As the population of the basin increased over time, some of the most bitter disagreements involved droughts and floods. For example, in 1928 New York City started to draw water from several tributaries of the Delaware River, putting New York in direct conflict with villages and towns of New Jersey and Pennsylvania that were using the Delaware for their water supply. In 1929 New Jersey initiated (and Pennsylvania joined) a bill of complaint asking the U.S. Supreme Court to stop New York City from diverting water from the Delaware River basin. In 1931, the Supreme Court ruled that the interests of each of the four river-basin states—Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania—should be given equal consideration in the management of the shared waterway. The court allowed New York City to draw 440 million gallons of water a day from the Delaware and its upstream. That decision, however, did not resolve the competition for river water.

To resolve such disputes over the river’s shared resources, in 1936 the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and New York formed the Interstate Commission on the Delaware River Basin (Incodel) to control and prevent water pollution, plan the conservation of water supply for the use of the cities, and plan development along the banks of the entire river.

Incodel proceeded aggressively to press all four state legislatures to pass pollution-control measures. To support its campaign it prevailed on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to conduct scientific water pollution studies and to work with regional companies on a new voluntary plan to reduce oil and refuse dumping. However, industrial production during World War II reversed the modest improvements achieved during the 1930s. During the war years companies were allowed to dump more waste than at any other time in history. Regulators were unwilling to restrain producers supporting the war effort. The Port of Philadelphia became so vile that a number of ships simply refused to dock at their scheduled destination. Tests indicated that the river water entering the city’s water treatment plants was the most polluted of any major U.S. city.

Delaware River Basin Compact

Seeking a new approach to shared management of this critical resource, the four states in 1961 joined with the federal government to create a successor organization. In that year President John Kennedy (1917-63) signed the Delaware River Basin Compact creating the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), which absorbed the staff and assets of Incodel. In addition to the basin’s four state governors, the compact also included the regional U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—becoming the first equal partnership between federal and state governments in river basin management. The DRBC was not intended to coerce participating jurisdictions to comply with the majority preference, but to serve as a framework for negotiating tensions and conflicts in the management of the river.

As the first ever federal-state watershed compact, the DRBC was the first agency to specify load allocations for river polluters in 1968, holding them to standards more stringent than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued years later. The DRBC’s efforts were strengthened in 1972 when Congress passed the Clean Water Act, making it illegal to dump pollutants into the nation’s rivers without a permit from EPA and required wastewater treatment plants to improve their standards. The key to that law’s success in the Delaware watershed, as elsewhere in the U.S., was that Congress supplied 75 percent of the money needed to upgrade local plants. Between 1972 and 1990, over $1.5 billion was spent on wastewater treatment plants along the Delaware between Wilmington, Philadelphia, and Trenton, noticeably improving levels of dissolved oxygen.

In the 1960s and again in the early 1980s, the DRBC focused much of its effort on mediating among the states during a series of punishing droughts. Then in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the river experienced three major floods in three years (2004–2006) that severely damaged homes and land along the river banks. Enraged residents of towns along the Delaware, mainly from the Water Gap south to the Lambertville/New Hope area, blamed the floods on New York City leaders who insisted on keeping the water levels too high in the reservoirs that served their city, as a hedge against shortages. In response to the standoff the DRBC crafted a Flexible Flow Management Program in 2007. The plan allowed a seasonal drawdown of a specific volume of water from the reservoirs, based on forecasts of likely snowpack buildup during the winter.

Although this approach to meeting the conflicting goals of the state governments did not satisfy all parties equally, local governments along the river worked in association with DRBC and the Federal Emergency Management Agency to implement the plan.

Shared Governance of the Philadelphia Port

Like the river’s shared hazards, its infrastructure also called for coordinated management. Among the most important installations have been the bridges that connect Pennsylvania with New Jersey. In 1919 the two states created the Delaware River Bridge Joint Commission to build a bridge connecting central Philadelphia with downtown Camden and to collect tolls to maintain that bridge. To great fanfare, the Delaware River Bridge (later renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge) opened in 1926 just days before Philadelphia celebrated the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Over the decades, the agency renamed itself the Delaware River Port Authority (DRPA) and constructed three more bridges across the river—the Walt Whitman, Commodore Barry, and Betsy Ross—along with a bistate rail line (PATCO) to carry riders from the New Jersey suburbs into and out of Philadelphia.

(Photograph by Elevated Angles for Visit Philadelphia)

The mainly constructive relations between the two states within the DRPA hit a snag in the mid-1990s over a controversial plan to deepen the Delaware to forty-five feet by dredging the river bottom. Since 1941, the river’s main channel from Philadelphia and Camden southward to the mouth of the Delaware Bay had been maintained at a depth of forty feet. But in the final decade of the twentieth century, port planners recognized the ship channel needed to be deeper if Philadelphia’s port wanted to compete against other East Coast ports like Baltimore and Norfolk, Virginia, that could accommodate larger ships coming from Asia through the Panama Canal.

Political leaders in both Delaware and New Jersey strenuously opposed digging up the riverbed for fear that toxic dredge materials from the river bottom would be disposed of in their states. Prominent environmental groups including the Sierra Club also worked to block the project. To meet those objections, Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell (b. 1944), a champion of the project, agreed to allow those dredge spoils to be deposited in abandoned coal mines in Pennsylvania. Ultimately, the federal government made the decision, based on the principle of federal supremacy over navigable waterways. In October 2009 the Army Corps of Engineers decided to allow the project, and dredging began in March 2010. The project to deepen the Delaware River main channel to forty-five feet was completed in February 2020.

Despite periodic disagreements about how the river’s assets should be preserved, examples of regional cooperation like the Delaware River Basin Commission and the Delaware River Port Authority showed that broad consensus existed about the river’s value to all parts of the region.

However, government alone, even when working across jurisdictional boundaries, could not carry the entire burden of protecting the river. In 2014 the William Penn Foundation launched a Delaware River Watershed Initiative committing $100 million to coordinate the work of over sixty community associations and nonprofit organizations. All these nongovernmental groups agreed to work on land preservation and restoration projects on the river’s banks as a way to reduce runoff from farm fields, stem the loss of forests, and prevent the depletion of groundwater. The partners agreed to monitor water quality at five hundred sites in the watershed and share information.

In the Supreme Court decision of 1931 allocating rights to the waters of the great Delaware River to the four states comprising its watershed, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841–1935) remarked, “A river is more than an amenity, it is a treasure.” As a treasure held in common, the Delaware River provided those living on its banks with countless opportunities to make use of its bounty. In so doing, this treasure that crosses local, county, and state boundaries, tested the region’s capacity to cooperate in preserving its waters from overuse and even destruction. Through a combination of local initiative and federal resources, the region’s inhabitants largely proved themselves capable of meeting that challenge.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- How the Clean Water Act fixed the Delaware River’s pollution problem (WHYY, January 12, 2019)

- A battle brews over use of the Delaware River: Recreational vs. commercial (WHYY, March 28, 2022)

- The Delaware River’s invisible threats (WHYY, January 15, 2019)

- Could these simple ‘Seabins’ give us better information about the plastics hiding in Philly’s rivers? (WHYY, June 8, 2022)

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation announces $15 million for Delaware River watershed (WHYY, August 25, 2022)

- Life along the Delaware (WHYY)

Links

- Washington's Crossing Reenactment (annual event)

- Commentary on Emanuel Leutze’s Symbolic Scene of Washington Crossing the Delaware (National Endowment for the Humanities)

- Rising Nation River Journey event hosted by the Lenape Nation of PA (every four years)

- Delaware River Stories

- Back When We Burned Trash On The Delaware River (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Delaware River Waterfront Once A Hotspot For Millionaires (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Phantom Piers, Lost Raftsmen, and Deforestation on the Delaware River (Hidden City Philadelphia