AIDS and AIDS Activism

By Dan Royles | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Doctors in Philadelphia diagnosed the first local case of what would later become known as AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) in September 1981, just months after the Centers for Disease Control first reported mysterious outbreaks of pneumocystis pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma among gay men in New York and Los Angeles that marked the beginning of the recognized AIDS epidemic in the United States. Since pneumocystis pneumonia is rarely seen in healthy patients but common to those with weakened immune systems, and Kaposi’s sarcoma is a skin cancer otherwise seen among elderly Mediterranean men, the presence of these diseases in otherwise healthy young men signaled the potential for a serious public health crisis. Researchers later discovered the cause of AIDS to be the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which replicates in the human body by killing cells that are vital to immune function, over time depressing the ability of the host body to fight off infections.

Although the number of new cases in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco multiplied quickly over the first two years of the epidemic, at first the number of people with AIDS in Philadelphia rose slowly. Within the first year, only seven cases were reported locally, but by early 1983 trends in Philadelphia seemed to be catching up to the rapidly growing epidemic witnessed in New York and California. The disease also appeared in New Jersey, particularly in the urban corridors between Philadelphia and New York and between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, and in Delaware.

As gay men watched their friends and lovers die in increasing numbers, they organized in response. Philadelphia Community Health Alternatives (PCHA, later known as the Mazzoni Center), a health clinic founded in 1979 to serve the local lesbian and gay community, formed the Philadelphia AIDS Task Force to provide social services to those affected and offer information about AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases through a local hotline. Meanwhile, social clubs like the Gay Men’s Chorus and Girlfriends Motorcycle Club joined forces to raise funds for PCHA’s education and prevention efforts.

Spread of AIDS

By the middle 1980s public health authorities recognized that the AIDS epidemic had grown beyond the communities of gay men in which doctors first identified the disease. Researchers in the United States and France had identified HIV as the cause of AIDS in 1983, and thus definitively determined that the disease could be transmitted through blood-to-blood contact, including needle-sharing among intravenous drug users, blood transfusions, and from an infected mother to her unborn child. At the same time, in cities around the country, reports showed the growing incidence of HIV and AIDS among African Americans and Latinos, particularly within networks of intravenous drug users and among their sexual partners and young children. Although those in this “second wave” of new cases had likely been infected for some time, their low access to medical care combined with the long latency period of HIV, during which time the virus spreads throughout a patient’s system but does not produce symptoms, to initially mask the prevalence of AIDS within communities of color.

In Philadelphia, by 1985 African Americans made up almost half of all reported AIDS cases, and the majority of cases among people under twenty five years old. David Fair, a longtime local gay activist and secretary-treasurer of a local predominantly Black health care workers’ union, and Rashidah Hassan, a nurse who had worked with PCHA and its AIDS Task Force, became dissatisfied with the groups’ failure to effectively reach out to African Americans at risk of contracting HIV. To stem the rising tide of new infections in Philadelphia’s Black community, in 1986 they founded Blacks Educating Blacks About Sexual Health Issues (BEBASHI), one of the nation’s first Black AIDS service organizations. Perceiving that the AIDS Task Force’s efforts to reach out to the Black community had been undercut by its reputation as an all-white organization, BEBASHI representatives worked through existing social institutions like African American churches so that their education and prevention messages that would resonate with Black audiences. In New Jersey, Project IMPACT (Intensive Mobilization to Promote AIDS Awareness through Community-based Technologies) also reached out to African American leaders in urban areas.

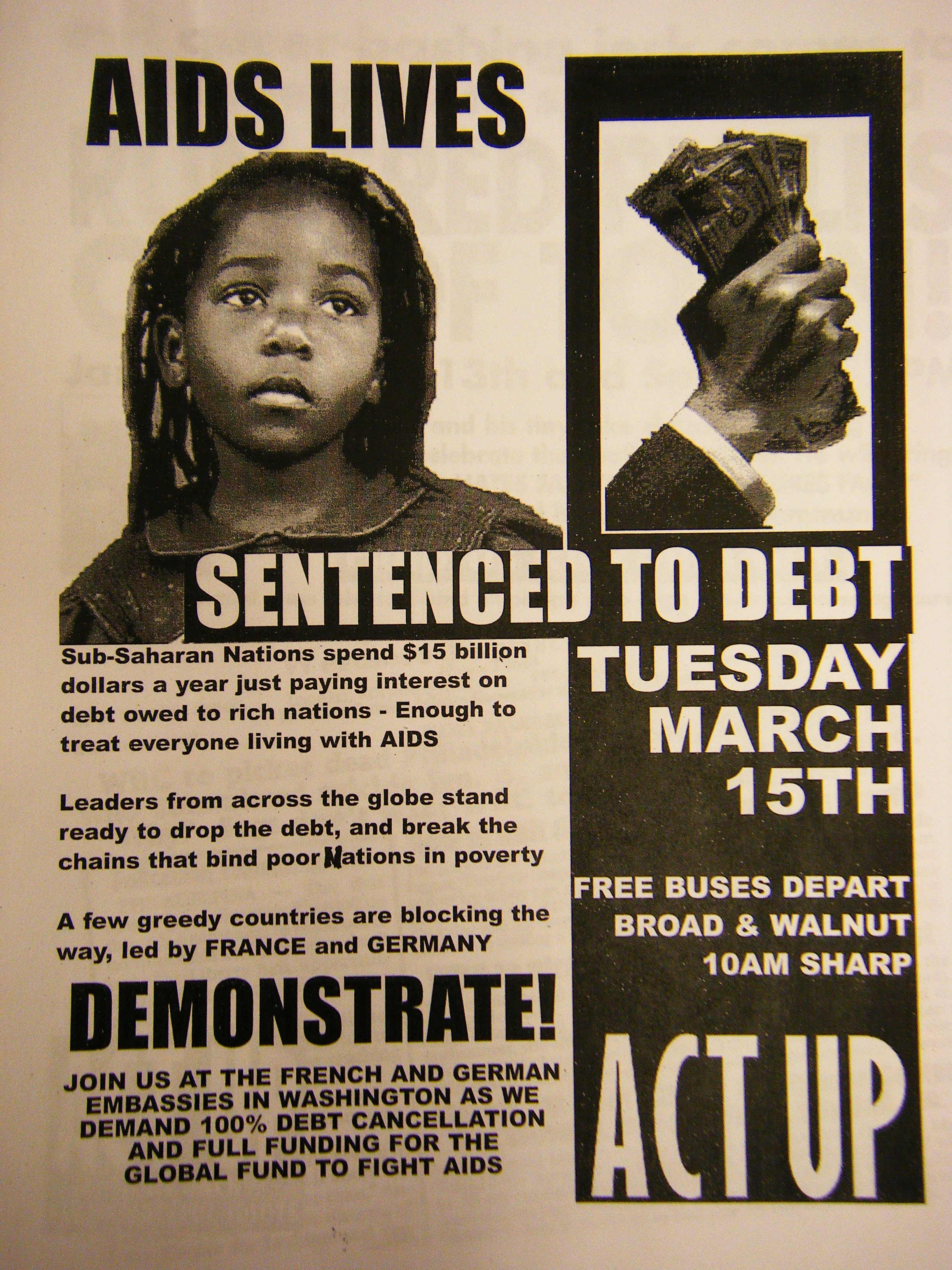

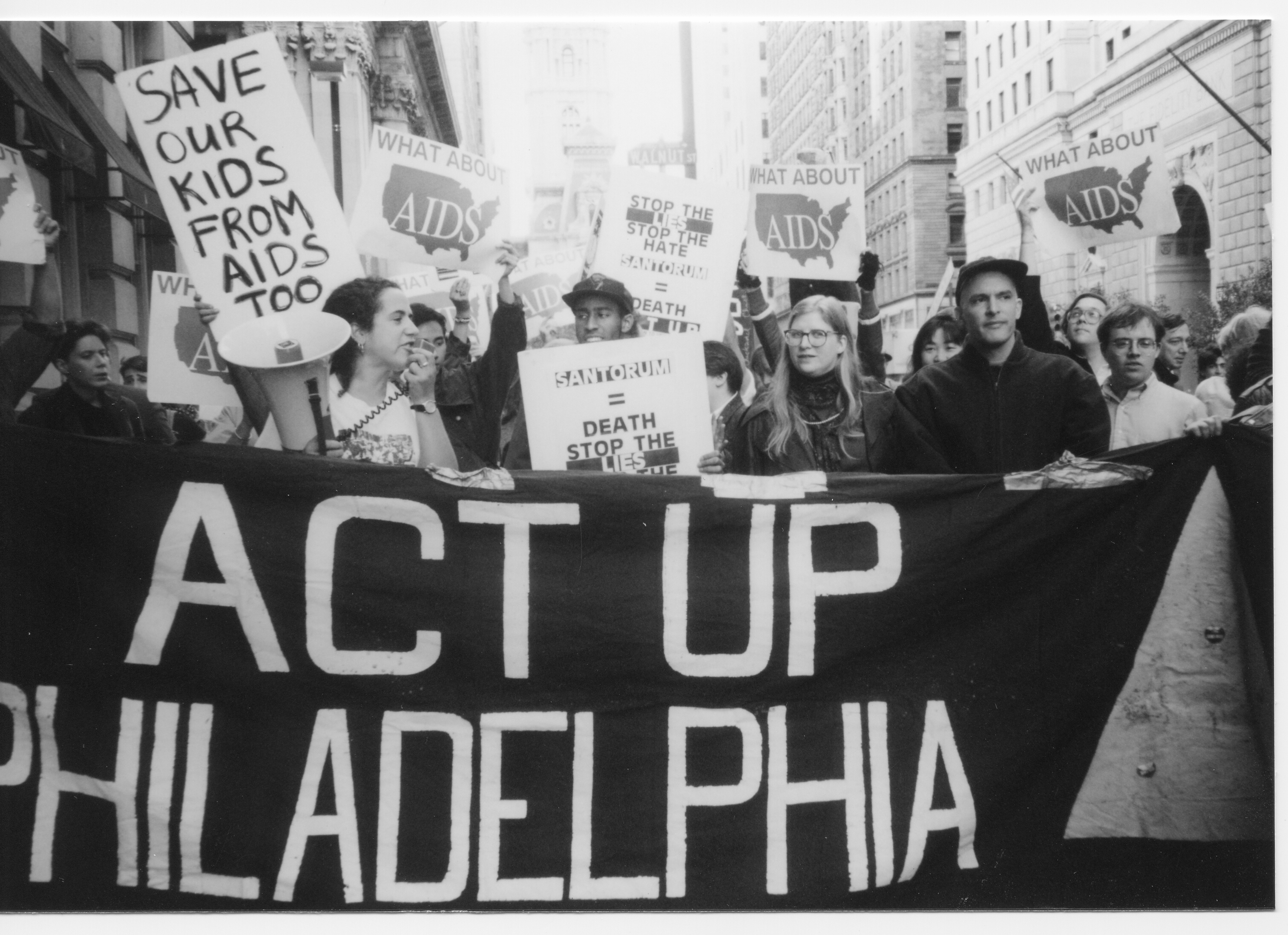

In 1987, as the AIDS community nationwide became frustrated with the dearth of effective treatments and President Ronald Reagan’s reticence on the epidemic, grassroots AIDS politics took a radical turn. In March, a group of New York activists founded the inaugural chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), an organization whose protest actions became the public face of AIDS advocacy in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The group quickly spawned a network of chapters in cities across the country and abroad, including Philadelphia, South Jersey, and Delaware.

Dramatic Demonstrations

Members of the Philadelphia branch of ACT UP began staging theatrical “die-ins” and other dramatic demonstrations to highlight the human cost of high prescription drug prices and inadequate public health policy. To protest the Catholic Church’s opposition to condom use, in May 1991 around one hundred ACT UP Philadelphia members interrupted a prayer service for people with AIDS conducted by Archbishop Anthony Bevilacqua and tried to place wrapped condoms near his hands and feet, shouting, “These will save lives–your morals won’t.” In addition to public protests, ACT UP became well known for creating memorable visual messages to both educate people about AIDS and mobilize those affected by the epidemic. In this vein, during one holiday season the Philadelphia chapter circulated stickers featuring an HIV-positive Santa Claus with the tagline, “If only Reagan and Bush had told the truth, Santa wouldn’t have to die from AIDS.”

During the mid-1990s, ACT UP declined in national prominence as the white gay men who filled much of the organization’s ranks passed away, grew tired of activism, or gained access to the highly effective (but expensive) class of new antiretroviral drugs that became available due to advances in HIV treatment research. The Philadelphia chapter, however, remained vital due to the recruiting efforts of a core group of members, who reached out to lower-income people of color, among whom the nationwide AIDS epidemic continued to grow fastest. The changing membership in turn shaped the direction of the group’s activism, as it increasingly focused on affordable housing, HIV prevention in prisons, and access to medications for impoverished people in the United States and throughout the developing world. Working with Health GAP (Global Access Project), a coalition of AIDS activists and allied organizations, Philadelphia ACT UP members pressured the White House to move forward with a coordinated response to the worldwide AIDS pandemic. This effort, supported by numerous AIDS action groups in Philadelphia and the Cooper Early Intervention Program in Camden, culminated in 2003 with President George W. Bush’s announcement of the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a five-year, $15 billion commitment funding HIV prevention and drug access programs in Africa. In 2008, Congress reauthorized the program through 2013, and expanded its funding to almost $48 billion.

Four Decades

As the epidemic entered its fourth decade, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health estimated that 1.3% of the city’s population was living with HIV or AIDS, about three times the national average. Center City and the surrounding area had the greatest prevalence of cases in Philadelphia County, with additional areas of high concentration in the Northeast, West Philadelphia, and around Germantown. Despite the city’s relatively large percentage of people living with HIV and AIDS, local trends reflected patterns of infection for the United States as a whole, inasmuch as the epidemic in Philadelphia disproportionately affected African Americans, and in particular men who had sex with men and women, among whom the disease was growing fastest.

Regionally, statistics collected by the Centers for Disease Control from the beginning of the epidemic through 2008 showed New Jersey ranking fifth-highest in number AIDS diagnoses among the fifty states; Pennsylvania ranking seventh; and Delaware ranking thirty-third (although in rate of cases per thousand population, Delaware ranked eighth-highest in the nation). By 2010 Philadelphia accounted for the highest proportion of AIDS cases in Pennsylvania, surpassing other counties by far (20,411 diagnosed cases from 1980 to 2010, compared with 1,098 in Montgomery County, 1,743 in Delaware County, 802 in Bucks County, and 603 in Chester County). In South Jersey, by 2010 the disease was most prevalent in Atlantic County.

In light of these realities, activists reignited the search for an AIDS cure. In 2009 a group of veteran Philadelphia activists, many of whom had been part of ACT UP chapters around the country during the organization’s heyday, founded the AIDS Policy Project to advocate for funding and scientific research on treatments to not only slow the spread of HIV within a patient’s system, but eliminate it altogether. In this way, Philadelphians sought to lead the way to the end of the AIDS epidemic once and for all.

Dan Royles is a Ph.D. Candidate at Temple University. This essay is derived from his dissertation research on the political culture of African American AIDS activism. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, University of Pennsylvania Press

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- City of Philadelphia AIDS Research and Data (Phila.gov)

- 2010 Delaware HIV/AIDS Report (Delaware Health and Social Services) (pdf)

- Striving for Equality: LGBT Activism in Philadelphia (Greater Philadelphia Roundtable discussion program, March 10, 2010, William Way Community Center)

- ACT UP and the AIDS Crisis Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)