City of Brotherly Love

Essay

When naming a newborn, you feel the weight of the decision, the fond hope that the right name might provide a push along a hoped-for path.

Even as names seek to nudge destiny, sometimes they merely set up irony: Faith, the fiery atheist; Victor, the embittered failure.

We can’t know all the thoughts that coursed through William Penn’s mind when he chose Philadelphia as the name for his new city, tucked onto the peninsula between the Delaware River and the Schuylkill. What we do know is that he chose boldly, aiming for the vault of heaven, daring irony to strike. The name he gave his city combined the Greek words for love (phileo) and brother (adelphos), setting up the enduring civic nickname: the City of Brotherly Love. Then Penn gave his city a street grid, a charter and a diplomatic first act that he hoped would enable it to live up to that name.

So how did it turn out, this Holy Experiment?

In modern popular culture, the verdict is often rendered with a sneer. “City of Brotherly Love” has turned into a phrase invoked more often in sarcasm than admiration.

In 1994, a Gallup Poll named Philadelphia America’s most hostile place. The most durable stereotypes about the city cluster around its fans’ penchant for booing and the colorfulness of its crime and corruption.

So William Penn’s choice can sometimes seem less destiny than irony.

But that judgment is neither complete nor fair. It ignores so much evidence.

Thanks to its founder’s impetus, and to the furthering energy of citizens from Benjamin Franklin to Richard Allen, from Lucretia Mott to John Wanamaker, from Richardson Dilworth to Mary Scullion, Philadelphia has remained one of America’s most inventive laboratories for exploring the civic potential of brotherly love and sisterly affection.

Destiny vs. Irony

Its history can be read as a long duel between destiny and irony, each vying to seize the upper hand in interpreting City of Brotherly Love. Philadelphia hosts a continuing dialogue about what brotherly love looks like in the civic sphere.

Be clear on this: It won’t do to reduce the notion of brotherly love to saccharine sentiment, to feelings only tender and soft.

Brotherly love does not imply the absence of conflict. Have you ever seen young brothers together? Their bond, strong as cement though it might be, gets expressed often as not through competing, jousting, gibes, and dares.

Anger is also a way to express caring, and in Philadelphia’s long history, a common one. Even today, some of Philadelphia’s best rowhouse citizens, who work doggedly to keep blocks decent and children safe, regard their hometown with what can only be called an angry love. It is loyal, it endures – but it has spikes and edges.

Like the nation that chose this city (and not by accident) as the spot to declare, then define, itself, Philadelphia has struggled to define brother. Who is inside the circle, who not?

The city’s story follows a cycle: high aspiration thwarted by weakness, strife, and division, then redeemed by a new round of noble struggle, which broadens understanding and widens the circle.

Penn himself, while nobly distinguished among colonizers for his fair and respectful relations with the native Lenape, had a blind spot about blacks. He owned slaves, and excluded blacks from many of the protections of Pennsylvania’s charter. While he founded his city upon a writ of religious tolerance that made it a rare and fruitful haven, he still excluded Catholics, Jews, and Muslims from the franchise.

Some Quakers later on repaired the lapses of Penn and other forebears, becoming leaders of the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad. Richard Allen and Absalom Jones helped advance Penn’s vision of religious freedom by insisting that it extended to the black person as well.

Abolitionist Lucretia Mott also sounded the clarion call that women, too, deserved a full role in America’s civic drama – that in fact, they were vital to bringing phileo to the polis.

As Philadelphia thrived, thanks in no small part to Penn’s legacy of openness, immigrants poured in. The inevitable backlash flared, especially in the nineteenth century. The Nativist riots of 1844 in Kensington were anti-Catholic bias at its ugliest. But in the long run the disorder helped make the case for the consolidation of the city into a larger, more governable but also more diverse whole.

Back and forth through the decades the dialogue flows around the city’s public squares, noisily and sometimes violently: Will the City of Brotherly Love embrace the destiny of its name, or reject it with cruel irony?

Along with dark moments – riots and beatings and tribal corruptions – Philly has birthed great testaments to shared civic bonds, from Fairmount Park to the settlement houses to the Free Library to the Mural Arts Program.

Its National League ball team once taunted Jackie Robinson most shamefully, but the Phillies now boast two beloved African American MVPs, whose jerseys are proudly worn on backs white as well as black.

Penn’s Legacy Persists

Through it all, the legacy of William Penn, his dreams, wisdom and example, still hums in the city’s blood – despite our cantankerous failings, our ritual suspicions about the latest bidders to join the circle of brothers and sisters.

Philadelphia, by its very name, is an unfinished dream of civic feeling and common purpose, an audacious wager upon the better angels of our nature.

We, the heirs and inhabitants of a city named for love, remain quick to anger, prickly and prideful, wary of the new.

It is our way, and God knows we have some reason for it.

But we are also stubborn in love, fierce in loyalty, and our embrace of those we let inside the circle is warm, protective and unfailing.

We need to let more in, and more easily, with fewer tests.

But we Philadelphians are young, still, in this Holy Experiment, and still learning.

May the Spirit that inspired civic heroes such as William Penn, Absalom Jones, Barnard Gratz and St. Katharine Drexel to the heights of brotherly love and sisterly affection continue to guide us.

Chris Satullo is Executive Director of News and Civic Dialogue at WHYY. (Author information current at time of publication.)

This essay, which also appeared in the Currents section of the Philadelphia Inquirer on March 20, 2011, and on Newsworks.org, is published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.

Related Topics: Tolerance, Intolerance, and Cooperation

Themes

Locations

- Northwest Philadelphia

- Center City Philadelphia

- North Philadelphia

- Northeast Philadelphia

- South Philadelphia

- Southwest Philadelphia

- West Philadelphia

Essays

- France and the French

- Gray Panthers

- Nationalities Service Center

- LOVE (Sculpture)

- Underground Railroad

- Philadelphia (Film)

- American Friends Service Committee

- Mennonites

- International Peace Mission Movement and Father Divine

- Black Power

- Poverty

- Liberty County

- Prisons and Jails

- South Asians

- Dogfighting

- Dogs

- Dispensaries

- Nativism

- SPHAS

- Women’s Clubs

- Orphanages and Orphans

- Armstrong Association of Philadelphia

- Magdalen Society

- Koreans and Korea

- Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

- Free Black Communities

- Boarding and Lodging Houses

- Nursing

- MOVE

- Twist (The)

- Social Dancing

- Mexicans and Mexico

- Freemasonry

- Roman Catholic Parishes

- Greek War for Independence

- Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans

- Historical Societies

- Pennsylvania Prison Society

- Working Men’s Party

- New Year’s Traditions

- United States Colored Troops

- TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)

- City Merchant (The); or, The Mysterious Failure

- Reminder Days

- Civil Defense

- Girard’s Bequest

- Trade Unions (1820s and 1830s)

- House of Refuge

- Kwanzaa

- Liberians and Liberia

- Bloody Fifth Ward

- Police Department (Philadelphia)

- Sports Fans

- Mummers

- Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

- Loyalists

- Free African Society

- Religious Society of Friends (Quakers)

- Quaker City (The); Or, the Monks of Monk Hall

- Country Clubs

- Fugitives From Slavery

- Philadelphia Award

- Almshouses (Poorhouses)

- Puerto Rican Migration

- Mormons (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints)

- ODUNDE Festival

- Saint Patrick’s Day

- Union League of Philadelphia

- Vagrancy

- Greater Philadelphia Movement

- Co-Working Spaces

- Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton’s Experiments

- Alien and Sedition Acts

- Educational Reform

- Vigilance Committees

- Garies (The) and Their Friends

- Native American-Pennsylvania Relations 1681-1753

- Treaty Negotiations with Native Americans

- Law and Lawyers

- Gothic Literature

- Riots (1830s and 1840s)

- Papal Visits

- Martin Luther King Jr. Day

- Christiana Riot Trial

- Modern Chivalry: Containing the Adventures of Captain John Farrago, and Teague O’Regan, his Servant

- Pennsylvania Hall

- Junto

- Native and Colonial Go-Betweens

- Mount Airy (West)

- Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens

- Duffy’s Cut

- Killers (The): A Narrative of Real Life in Philadelphia

- General Strike of 1910

- Walking Purchase

- Murder of Octavius Catto

- Friends Neighborhood Guild

- Indian Rights Associations

- Columbia Avenue Riot

- Crime

- Playgrounds

- Immigration and Migration (Colonial Era)

- Lynching

- Gayborhood

- Fort Wilson

- Philadelphia Plan

- Education and Opportunity

- Treaty of Shackamaxon

- African American Migration

- Byberry (Philadelphia State Hospital)

- Settlement Houses

- Public Baths and Bathing

- Immigration (1790-1860)

- Immigration (1930-Present)

- Animal Protection

- Nativist Riots of 1844

- Delaware Avenue (Columbus Boulevard)

- Pennhurst State School and Hospital

- Ladies Association of Philadelphia

- Abolitionism

- Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition (1913)

- Octavia Hill Association

- Civil War Sanitary Fairs

- Greeks and Greece (Modern)

- Anglican Church (Church of England)

- Northwest Philadelphia

- Lutherans and the Lutheran Church

- Missionaries

- African American Museum in Philadelphia

- Episcopal Church

- Buddhism

Map

Philadelphia’s long connection with France and the Francophone world took shape over several centuries. In 1889, French Philadelphians commissioned the Saint Joan of Arc statue on Kelly Drive.

Jonathan Demme's 1993 film 'Philadelphia' attempted to reform the public understanding of AIDS at a time of prejudice and hate. In the context of the film, the Mellon Bank Building housed the law firm of protagonist Andy Beckett.

American Friends Service Committee

The AFSC, founded by Philadelphia Quakers in 1917, coordinated pre- and postwar relief projects across the world starting in the twentieth century. Many members attended the Germantown Friends Meeting House.

German Mennonites were among the first settlers in Philadelphia in the early 1680s. The 1770 Germantown Meetinghouse remains open as a museum and historic site.

International Peace Mission Movement and Father Divine

The religious Peace Mission Movement was known for its civil rights activism as well as its 'cultic' qualities. The Divine Lorraine Hotel in North Philadelphia hosted many of the Mission's social welfare activities.

The Black Power movement came to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s. From a storefront headquarters, the Philadelphia Black Panther Party distributed free lunches and information about the organization.

The Northeast Municipal Services Center, relocated from Roosevelt Boulevard and Welsh Road in 2016, was opened in 1985 by Mayor Wilson Goode. The Center was Goode's way of addressing the concern of Northeast Philadelphia residents that felt resources were being focused in other parts of the city and municipal services.

Philadelphia was at the center of the early prison reform movement, first introducing individual cells at Walnut Street Prison and later solitary confinement. The city's prisons later became notorious for conducting experiments on prisoners and a high rate of incarceration.

South Asians arrived in Philadelphia after changes in immigration policy, lured by university and skilled employment. Here they established businesses, cultural organizations, and religious centers, including several suburban Hindu Temples.

Free clinics known as dispensaries served the “working poor” from the eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries. The Philadelphia Dispensary for the Medical Relief of the Poor, considered the nation’s first, opened in 1786 and erected a new building on Fifth Street in 1801.

Although initially focused on self-improvement, women’s clubs in the Philadelphia region, like the New Century Club, quickly extended their goals to include community activism.

By the early nineteenth century in Philadelphia, private groups established orphanages to care for children whose parents could not support them because of poverty or death. One such institution was Girard College, founded in 1848.

Armstrong Association of Philadelphia

The Armstrong Association of Philadelphia, an interracial organization that aided African Americans with job placement and adequate housing, operated a learning and social center at the Thomas Durham Public School.

Founded in 1800 and located at Twenty-First and Race Streets, the Magdalen Society of Philadelphia was the first institution in the United States concerned with caring for and reforming “fallen women.”

Koreans became one of the top ten new immigrant groups in the Philadelphia region by 1970. Korean businesses grew in Montgomery County communities such as Elkins Park and Cheltenham.

Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

Founded in 1882 to address social issues in Philadelphia, the Children's Aid Society of Pennsylvania merged in 2008 with the Philadelphia Society for Services to Children and formed Turning Points for Children.

Mother Bethel church in Philadelphia is the oldest AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church in the United States. Churches were staples for black communities and continue to hold places of leadership.

Philadelphia's boarding and lodging houses provided affordable, if less than desirable, living quarters and meals to their inhabitants. They were also a means for recent immigrants and women to support themselves and their families.

Chubby Checker ushered in a new dance craze with his recording of 'The Twist.' He is celebrated, together with other South Philadelphia musicians, in a mural at Broad and Tasker Streets.

From the minuets and waltzes of the city's early years to jazz, swing, and the tango, social dance has been an active part of the Philadelphia area's social scene. Dance schools pepper the region, including one on Rittenhouse Square.

Mexicans became the region’s second-largest immigrant group in the early twenty-first century, impacting the region's culture and economy. The Mexican Cultural Center of Philadelphia is in the Bourse Building, near Independence Hall.

Philadelphia was one of the first American cities with a branch of the fraternal society known as the Freemasons, whose ornate temple in Philadelphia is one of the most prominent in all of Freemasonry.

Philadelphia has been home to Catholic parishes since the colonial era. Despite declines in recent decades, the church maintains a strong presence. Old St. Joseph's on Willings Alley opened in 1733.

During the Greek War for Independence (1821-28), Philadelphians helped arouse public sentiment in favor of the Greeks and raised money and provisions to aid the cause. The Second Bank was modeled on the Parthenon of Athens.

Relations between Philadelphia and Puerto Rico reach back to colonial times. Today, North Fifth Street's “El Bloque de Oro,” or “Golden Block,” remains a vibrant neighborhood of Latino culture and commerce.

Since the early nineteenth century, a number of historical societies have called Philadelphia home, from small religious and local history groups to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Spurred by reports of deplorable conditions at the Walnut Street Jail, a nondenominational group of religiously motivated activists set out to reform Philadelphia's prisons. Their reforms soon spread to prisons around the world.

Rooted in a trade union coalition that formed near this location, the Working Men's Party organized the city's laboring class, gained seats in city government, and pressured the city and state to change laws that impacted poor and working-class citizens.

From a quiet holiday for visiting friends, to Mummers and fireworks, Philadelphians have always loved to celebrate New Year's. With new immigrants came new holiday traditions. The Mummers Museum is on 'Two Street.'

Over 10,000 African Americans from the Philadelphia area enlisted in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War and trained at Camp William Penn. Some earned the highest military accolades for their service.

TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)

Local record label Philadelphia International Records scored a #1 hit when they records 'TSOP' -- The Sound of Philadelphia -- for the national television program Soul Train.

City Merchant (The); or, The Mysterious Failure

A fictional account of real events, The City Merchant by John Beauchamp Jones blames the tumultuous events of the antebellum period on abolitionists and unscrupulous real estate deals. The Second Bank of the United States is part of the plot.

The annual Reminder Days demonstration at Independence Hall predated the Stonewall riots and stand among the first gay rights demonstrations in the United States.

From colonial militias to Cold War fallout shelters and nuclear bomb drills, Philadelphia's citizens have prepared for disaster throughout the city's history. Civil Defense remnants still show up, including fallout shelter signs at City Hall.

Stephen Girard left most of his fortune to Philadelphia for charitable causes. His estate funded infrastructure works, residential developments, and schools—most famously, Girard College for white orphan boys.

Philadelphians organized trade unions and supported one of the most successful labor demonstrations in the antebellum period, the General Strike of 1835. Soon after the strike began, protesters filled the Merchants' Exchange on Walnut Street.

Established in 1826 at the later intersection of Fairmount and Ridge Avenues, the Philadelphia House of Refuge provided an alternative to prisons for incarcerating juvenile delinquents and child vagrants.

Greater Philadelphia has had close links to Liberia since free blacks and abolitionists helped colonize Liberia’s founding in the early nineteenth century. In recent times, many Liberians fled violence at home, and for some the escape route led to 'Little Monrovia” along Woodland Avenue near Sixty-Sixth Street.

Philadelphia’s Fifth Ward, south of Chestnut near the Delaware River, became infamous in the late nineteenth century for election-day riots among Irish, Black people, and the police. In the twentieth century, the area was cleaned up and rebranded as Society Hill.

Police Department (Philadelphia)

The Philadelphia Police Department was created in 1854, and since 1962 has been headquartered in the Police Administration Building also known as 'The Roundhouse' on Race Street.

Philadelphia is known for the enthusiasm of its sports fans, and Citizens Bank Park, which opened in 2004 as home of the Philadelphia Phillies baseball team, is a hotspot of cheers and jeers during the baseball season.

Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

Military veterans began organizing during the waning days of the Revolutionary War and continued to form organizations such as the Philadelphia Veterans Advisory Commission, established in 1957 and located in City Hall.

A nondenominational mutual aid society, the Free African Society was founded in 1787 by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. Jones also led the the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, originally located at Fifth and Adelphi Streets (St. James Place).

Philadelphia was Quaker William Penn's 'holy experiment' in founding a colony of virtuous Quakers. The influence of the church can still be felt today, and the Arch Street Meeting House still stands.

Quaker City (The); Or, the Monks of Monk Hall

The Quaker City, a Gothic novel written in the 1840s by George Lippard, is set in part along the Delaware River waterfront, later developed as Penn's Landing.

Country clubs originated in the 1890s as elite, family-oriented havens usually emphasizing golf. Among the earliest clubs was the Philadelphia Country Club, now located in Gladwyne.

Because of its abolitionist posture, Pennsylvania became a haven for fugitive slaves from neighboring states. Slave catchers and abolitionists tangled, and some cases were decided by hearings in what came to be known as Independence Hall.

The Philadelphia Award, founded in 1921 to annually honor a citizen for service that advances 'the best and largest interests of Philadelphia, was presented at the Academy of Music on Broad Street until 1950, when the ceremony moved to the Barclay Hotel.

The Friends Almshouse, operated by the Quakers in 1713, provided poor relief for Quakers. Over time, almshouses evolved from being run by voluntary associations to ones operated by government.

Puerto Ricans migrated to the Philadelphia region in search of economic opportunity. The clustering of Puerto Rican-owned businesses around Fifth Street and Lehigh Avenue developed into the “Golden Block” (El Bloque de Oro) retail area.

Drawing inspiration from African cultural heritage, specifically the Oshun Festival of the Yoruba people in Nigeria, the annual ODUNDE Festival draws thousands to South Philadelphia.

Once a religious holiday and a political parade, Saint Patrick’s Day transformed over two centuries into a largely secular celebration reflecting the changing culture of Philadelphia’s Irish population and of the city at large.

During the Civil War, a group of pro-Union Republicans founded the Union League. Since then, it has transformed into the city's premier social club.

After nearly 70 years of domination by the Republican Party, Democrats formed the Greater Philadelphia Movement, whose influence led to reforms and improvements such as the Food Distribution Center in Southwest Philadelphia.

Dozens of co-working spaces opened (and some failed) in the early decades of the twenty-first century in Greater Philadelphia, including the pioneering Indy Hall on North Third, offering shared work space designed to foster a collaborative atmosphere

Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton’s Experiments

Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton's Experiments, by Sarah Josepha Hale, advocated colonizing free African Americans in Liberia. The Pennsylvania Colonization Society once occupied an office on a street opposite of Washington Square.

Passed while Congress met in Philadelphia, the Alien and Sedition Acts created a political backlash during the presidency of John Adams.

The Friends Select School has helped make education accessible to every student, continuing a legacy that started with the first Quaker 'select school' in 1689.

Vigilance Committees (sometimes called Vigilant Committees) formed to protect fugitives and potential kidnap victims. Robert Purvis was one of Philadelphia's most prominent abolitionists. His home at Ninth and Lombard Streets had a secret area for hiding slaves.

The central event in the novel, 'The Garies and Their Friends,' is a graphically-rendered race riot, evoking the historical riots of 1834, 1838, 1842, and 1849. One of these riots, the Lombard Street Riot, has a historical marker located at Sixth and Lombard Streets.

Native American-Pennsylvania Relations 1681-1753

The 1737 Walking Purchase in Bucks County is just one example of interaction between colonists and the Lenapes, or Delawares, who had been dealing with Dutch and Swedish colonists for decades.

Treaty Negotiations with Native Americans

From the arrival of Europeans in the seventeenth century through the era of the early republic, treaties were an important tool in diplomacy between native nations, colonial Pennsylvania, and the federal government.

The law profession in Philadelphia dates back to the days of William Penn. Over the city's three centuries, it has evolved into a diverse and vital aspect of the city community.

Philadelphia is the birthplace of gothic literature in America. One of its early purveyors was Edgar Allan Poe, who lived in Philadelphia for six years. His home at 530 N. Seventh Street is a national historical site.

Increased job competition among ethnic and racial groups, in particular between Irish and Black workers, brought intermittent fighting that exploded into a full-scale riot in August 1842, with its focus point at Sixth and Lombard Streets.

The public Mass held by Pope John Paul II on Logan Circle on October 3, 1979, drew more than a million people, by police estimates, stretching on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway from City Hall to the Art Museum and beyond.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day observances have been held annually in Philadelphia since the 1970s. A focal point is Girard College, where King held a rally in 1965, as well as a ceremony at the Liberty Bell.

In 1851, an attempt to recapture escaped slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania, turned into a riot in which one man was killed. The trial of one of the participants at the Old State House (Independence Hall) reflected growing abolitionist sentiment.

The novel <i>Modern Chivalry</i> was published in installments from 1792 to 1815, wryly documenting life in the new republic. One episode targets pretensions at the American Philosophical Society.

Tension over abolition led to a number of riots, one of the most notable being the 1838 destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, a meeting place for antislavery groups on Sixth Street about two blocks north of Independence Hall.

Native and Colonial Go-Betweens

In the colonial era, as conflict between the Europeans and displaced Native American tribes rose, go-betweens helped soothe tensions. Native Americans and Europeans met near Second and Market Streets in 1728 in response to tension on the western frontier.

West Mount Airy is an economically thriving middle-class neighborhood known for being one of the most racially integrated communities in the country.

'Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens'

Musical Fund Hall is where a convention altered the Pa. Constitution to disallow voting by black residents, a move that inspired the essay 'Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Philadelphia,' which argued against ratification.

At Duffy’s Cut, a railroad construction site in Chester County, Pennsylvania, fifty-seven Irish immigrant railroad workers died amid a cholera epidemic in the summer of 1832 and were buried in a mass grave.

Killers (The): A Narrative of Real Life in Philadelphia

Site of California House tavern, where a gang attack on October 9, 1849, led to the two days of violence that became known as the California House Riot, leaving four dead. In 1849, Rodman was known as St. Mary Street.

The Callowhill Depot built by the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company to house their fleet of streetcars.

The Walking Purchase, in which three 'walkers' started at this point and traveled for a day and a half northeast, defrauded the Delaware Indians out of a vast amount of land.

On October 10, 1871, during a tumultuous and racially polarized Election Day in Philadelphia, Ocatvius V. Catto was shot around here on south street, a block away from his home. Catto spent his life fighting against segregation and discrimination.

The Quaker-Founded settlement house and neighborhood center, the Friends Neighborhood Guild, operates out out of this building to provide the adjacent community with a variety of services and educational opportunities.

Indian Rights Organizations (Nineteenth Century)

In Philadelphia, an incubator for reform movements, women and religious organizations led the way in considering the plight of Native Americans.

On Friday, August 28, 1964, a scuffle with police at this intersection of Twenty-Second Street and Columbia Avenue sparked a three-day riot involving hundreds of people hurling bottles at police and looting stores.

The influence of the American Playground Movement in the 1880's changed neighborhoods across Philadelphia, creating outdoor environments designed and equipped to facilitate children's play.

Immigration and Migration (Colonial Era)

Diverse peoples immigrating or migrating from Europe, Africa, and other American colonies before the Revolutionary War turned Philadelphia into colonial America's largest city.

Although only officially titled in 2005, the Gayborhood has served a vital role in the social and political struggles of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) peoples of Philadelphia since the 1940s.

On October 4, 1779, the house of James Wilson went from being the residence of a wealthy Philadelphia merchant to becoming a stronghold against a rowdy group of militiamen taking action against war profiteers.

Dubbed the “Philadelphia Plan,” the program requiring federal contractors to practice nondiscrimination in hiring tested the liberal coalition formed in the aftermath of the New Deal in Philadelphia and nationally.

The educational opportunities in Philadelphia have expanded greatly for students throughout the twentieth century, but the result has been a greater inequality between public and private schools.

The Treaty of Shackamaxon, otherwise known as William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians or “Great Treaty,” is Pennsylvania’s most longstanding historical tradition.

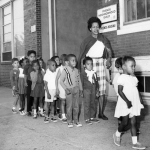

People of African descent have migrated to Philadelphia since the seventeenth century. Although African Americans faced discrimination, disfranchisement, and periodic race riots in the 1800s, the community attracted tens of thousands of people during World War I's Great Migration.

Byberry (Philadelphia State Hospital)

From the arrival of its first patients in 1911 to 1990, when the Commonwealth formally closed it down, the Philadelphia State Hospital, popularly known as Byberry, was the home for thousands of mental patients.

The settlement house movement spread to Philadelphia in the 1890s as a large influx of needy immigrants and unsanitary conditions in the city attracted the attention of middle-class, college-educated reformers.

Public bathing became a civil and social imperative in the Philadelphia region and elsewhere in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century.

The revival of immigration to Philadelphia and its surrounding region in the early nineteenth century provided one of the most powerful elements in reshaping the city's society. The German Society of Pennsylvania assisted German newcomers in finding jobs and housing.

For most of the decades since the United States’ immigration restriction acts of the 1920s, Philadelphia was not a major destination for immigrants, but at the end of the twentieth century the region re-emerged as a significant gateway.

Moral doubt over the cruel usage of animals has a long history in Philadelphia.With roots in the late nineteenth century, the PSPCA is among the most active in the nation.

On May 8, anti-immigrant mobs torched several private dwellings, a Catholic seminary, and two Catholic churches: St. Michael’s and St. Augustine’s.

Delaware Avenue (Columbus Boulevard)

Delaware Avenue played a significant role in the development of the city's maritime activity.

Pennhurst State School and Hospital

During eight decades of continuous operation, Pennhurst evolved from a model facility into the subject of tremendous public scandal and controversy before the federal courts ordered it closed.

Ladies Association of Philadelphia

In 1780, Esther De Berdt Reed penned a broadside titled “Sentiments of an American Woman” to rouse women to participate in the Revolutionary cause.

Few regions in the United States can claim an abolitionist heritage as rich as Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was founded in 1775 at the Rising Sun Tavern in Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition (1913)

The Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Octavia Hill Association of Philadelphia was founded in 1896 to provide clean dwellings at reasonable rents to some of the city’s poorest residents, who were often exploited by profit-hungry landlords.

Philadelphia's Civil War sanitary fairs represented the spirit of patriotic volunteerism that pervaded the city during the Civil War. These grassroots efforts climaxed at the Great Central Fair of 1864 in Logan Square.

Philadelphia's encounter with Modern Greece dates from the Greek War of Independence in 1821, and thousands of Greek immigrants arrived in the region beginning at the turn of the twentieth century. St. George's Greek Orthodox Cathedral was dedicated in 1921.

Anglican Church (Church of England)

Completed in 1753, Christ Church was a meeting place for Anglicans before the American War for Independence.

African American Museum in Philadelphia

The African American Museum in Philadelphia (AAMP) was the first major museum of Black history and culture established by an American city.

Christ Church was the site for discussions about the foundation of a new American church, separate from the Church of England.

Timeline

Related Reading

Dunn, Mary Maples and Richard S., Editors. The Papers of William Penn, 5 vols. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

Feldberg, Michael. The Turbulent Era: Riot and Disorder in Jacksonian America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Soderlund, Jean R., Editor. William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania: A Documentary History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983.

Related Collections

Charter of Privileges (digitized), American Philosophical Society, 105 S. Fifth Street, Philadelphia.

Penn Family Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia.

Links

- Recording of Greater Philadelphia Roundtable discussion program, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, March 23, 2011

- Has Philadelphia lived up to its reputation as the "City of Brotherly Love"? (Video by WHYY's Newsworks)

- "City of Brotherly Love" Discussion Summary, Greater Philadelphia Roundtable, March 23, 2011

- The Vision of William Penn (ExplorePAHistory.com)