Cumberland County, New Jersey

Essay

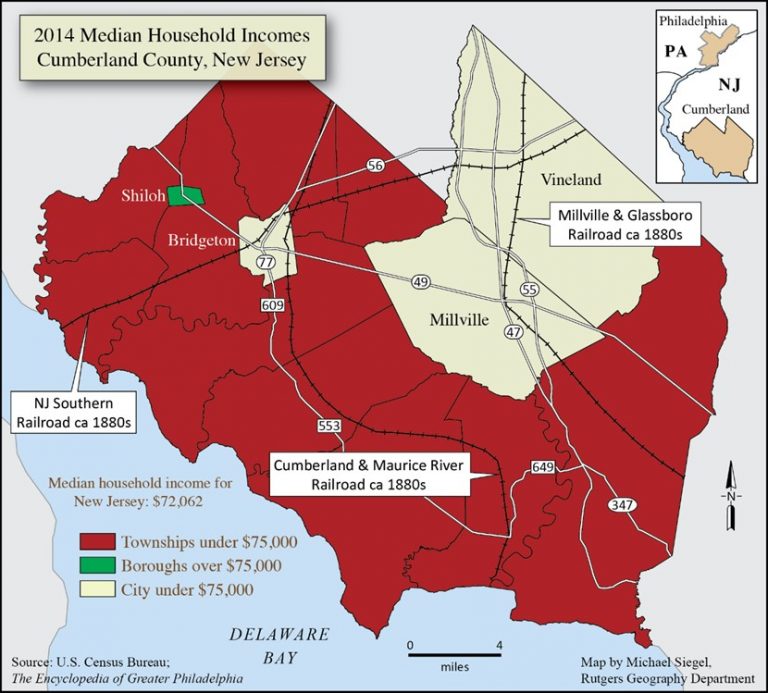

Cumberland County, New Jersey, located on the Delaware Bay about thirty-five miles south of Philadelphia, was formed from the southeastern part of Salem County in 1748. Its location and natural attributes led to a three-faceted economy that bridged centuries: rich farmland supported agriculture; two tidal rivers and the Delaware Bay provided a maritime economy; and deposits of silica sand fostered a glass industry. A diversity of immigrants, from Quakers, Presbyterians, and Baptists seeking religions freedom in the seventeenth century, to German glassblowers in the eighteenth, and Mexican and Central American agricultural workers in the twenty-first, generated three primary population centers, Bridgeton, Millville, and Vineland, separated by farmland interspersed with smaller settlements. As several industries declined in the second half of the twentieth century, they were only partially replaced economically making Cumberland the poorest county in New Jersey.

The area that became Cumberland County was first inhabited by the Lenni Lenape, whose settlements clustered along the rivers. Archaeology revealed evidence of ten thousand years of continuous occupation at the Indian Head Site in Deerfield Township. The Lenni Lenape population plummeted after settlement by the Dutch and Swedes, and the Indians claimed two of their people died for every Christian who arrived. About nine thousand people with ancestral links to the Lenni Lenape lived in Cumberland in the twenty-first century, and in 2018 New Jersey formally recognized the existence of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation.

John Fenwick (1618-83) established Salem in 1675, the first English settlement in West Jersey, but Swedes and Dutch had already been living in the area for forty years. The nucleus of the Swedish settlement was northwest of what became Cumberland County, but Swedes hunted and cut lumber along the Maurice River without obtaining title to the land. Swedish family names remained common in the area.

From the beginning, Fenwick planned to found a second town on the Cohansey River, fifteen miles southeast of Salem. He intended for it to be called Cohansey, but settlers renamed it Greenwich, probably after Greenwich, Connecticut. It was not until three years after Fenwick died that his executors laid out the town and began selling sixteen-acre lots.

Early colonists included Quakers, Presbyterians, and Baptists, attracted by the religious tolerance of Fenwick’s colony. The first settlers in Greenwich were Quakers from Salem, beginning in 1686. Sometime between 1680 and 1685, Presbyterians from Fairfield, Connecticut, and Long Island established New England Town on the east side of the Cohansey. About the same time, Baptists from Rhode Island and from Ireland also settled on the east side of the Cohansey, and Welsh Baptists came to Bowentown, between Greenwich and Bridgeton, by way of Swansea, Massachusetts.

Philadelphia Connections

Commercial connections with Philadelphia were extensive from the beginning. By the turn of the eighteenth century, Greenwich had become one of three official ports of entry in New Jersey. From 1695 until 1765, the West Jersey Assembly authorized Greenwich to hold semiannual fairs, in April and October, where anyone could peddle wares. Each fair attracted as many as twenty ships from Philadelphia, laden with goods to sell.

Cumberland County came into existence when the Tenth Assembly of New Jersey (after the unification of East and West Jersey in 1702) passed an act forming a new county from the southern part of Salem County on January 19, 1748. The act responded to citizens’ petitions, which objected to the inconvenience of all official business being carried out in Salem, at the extreme western edge of the county. The new county was named for the Duke of Cumberland (1721-1765), a contemporary hero credited with defeating Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie, 1720-1788) at the battle of Culloden in 1746.

Greenwich was the primary settlement at the time, and its citizens were so confident it would become the county seat they neglected to vote in a referendum to locate a new courthouse. The handful of residents of Bridgeton (then Cohansey Bridge) outvoted them, claiming the courthouse site, and, by default, designation as the county seat, to the consternation of the Greenwich inhabitants.

The rest of the area remained largely unpopulated in 1748 except for farms scattered along the two main rivers, the Cohansey and the Maurice, and a tavern located where Port Elizabeth was eventually laid out, on the Maurice in the southeastern section of the county. Of the 677 square miles that comprised the county, 484 were land and the rest water. The tidal Cohansey and the Maurice (pronounced Morris) Rivers drained toward the Delaware River, while the Tuckahoe River, a rare northern blackwater river, flowed toward the Atlantic Ocean. The high point in the county, 140 feet above sea level, was located in what became Upper Deerfield Township. At sea level, salt marshes bordered the Delaware River and the tidal reaches of the Cohansey and Maurice.

Slavery existed in Cumberland County, though not to the extent found farther north in the state. The estimate for 1790 was 120 slaves, decreasing to 75 by 1800; by 1830, only two people remained in slavery.

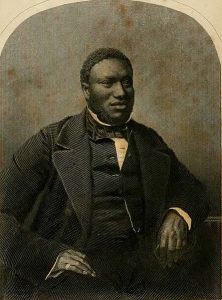

Cumberland County was a destination for slaves escaping from the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, accessible by boat across the Delaware Bay. The presence of abolitionist Quakers and free Black people created a haven. As the Underground Railroad evolved, one of the three main routes north through New Jersey became known as the Greenwich line, named for its southern terminus. While many escapees continued north, some settled in Cumberland, especially in the village of Springtown, in Greenwich Township, populated by five or six hundred freeborn and Black people who had escaped slavery. The settlement was operated as an armed camp, allowing in no unknown whites and subjecting all unknown Black people to questioning by a tribunal. According to Rev. Thomas C. Oliver (1818-1900), an Underground Railroad agent, “The strongest settlement among the colored people that I knew of was Greenwich. None were ever taken out of that place. The fugitives were as safe there as if they were in Canada.”

Quakers Set the County’s Tone

The Quakers set an egalitarian tone for the county. In 1843, when Philadelphia historian John Fanning Watson (1779-1860) visited Greenwich, his ancestral village, he noted that farmers ate at a common table with hired hands, both Black and white. It may have been the tolerant atmosphere promulgated by the Quakers that made possible the founding of Gouldtown, a historically prosperous settlement of free, mixed race people—primarily African American and white—that was established east of Bridgeton between 1755 and 1774, when Benjamin Gould (c. 1702–77) purchased a 249-acre tract. According to oral tradition, free Black men from the West Indies settled there and married women of Dutch and Finnish descent. Their descendants continued to inhabit the village, which survived as an unincorporated village in Fairfield Township, into the twenty-first century, when Philip Roth (1933-2018) made Gouldtown the hometown of his protagonist Coleman Silk in his 2000 novel The Human Stain.

The presence of Quakers and free Black people probably accounted for the county’s strong support of the Union during the Civil War. The attack on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, initiated an outpouring of patriotic fervor in the county, where “towns and villages…were decked with the starry banner, and every cross-road of any importance…had its flag waving in the air.” The first company of volunteers to be raised was the “Cumberland Grays,” (Company F of New Jersey’s Third Regiment); the company set off to war by way of Philadelphia on the steamer Patuxent. Many more companies were formed over the course of the war, and none was ever short of volunteers, some encouraged to join by the bounties offered by various towns and townships.

Those in the minority who sided with the Confederacy were sometimes treated harshly by the Unionists. Though New Jersey as a whole voted in 1860 and 1864 for Lincoln’s opponents, Cumberland County overwhelmingly supported him in both elections, by 58.58 percent and 56.75 percent respectively.

Following the initial seventeenth-century settlement, immigrants continued to be attracted to the county. The failure of the 1848 democratic revolution in Germany instigated a massive migration of Germans over the next decade, a sizable number of whom settled in Cumberland. Some worked in the glass factories and some started businesses. Italian farmers were recruited by Charles Landis when he founded Vineland in 1861 to realize his vision of a grape industry, and Italian migration continued well into the twentieth century. Many Italian families remained active in agriculture in the county.

The 1881 pogroms against Jews in southwest Russia initiated a worldwide relocation effort funded by wealthy Jewish philanthropists. Expanses of vacant land were purchased in South Jersey. Settlements were clustered on the Salem-Cumberland border, west of Vineland, with Rosenhayn (1883) and Carmel (1882) located in Cumberland. Farming was a struggle, as many of the settlers came from urban backgrounds. Many turned to clothing manufacturing to supplement their income, first under contract with manufacturers in Philadelphia and New York, and eventually with their own factories in Bridgeton, Millville, and Vineland.

African American Farm Labor

Farm labor in the first half of the twentieth century was provided by African Americans who moved north each year from Florida as crops were ready for harvest, and by Philadelphians of Italian descent whom labor brokers transported down for the season; members of both groups settled permanently in the county. Mid-century saw a rise in migrant laborers coming to the county from Puerto Rico, many of whom remained, particularly in Vineland. In the twenty-first century, farm laborers immigrated from Mexico and Central America. Bridgeton became a residential center for Hispanic immigrants, whose proportion of the population approached fifty percent. Some of the migrants commuted as much as an hour away for work in the fields.

Other significant immigrant groups included Ukrainians, Russians, and Greeks. To deal with a World War II labor shortage, Seabrook Farms, about three miles north of Bridgeton, recruited interned Japanese Americans and Latin Americans of Japanese descent, eventually relocating a population of three thousand. After the war, the corporation brought Europeans, primarily Estonians, from displaced persons camps. Eventually, five thousand workers and their families, from twenty-five countries, speaking thirty languages, formed the cohesive community of Seabrook, a rural global village.

Agricultural Economy

Ancient geological forces combined to give Cumberland a thriving agricultural economy from the beginning. A large river system, often referred to as the “proto-Hudson,” flowed in from the north, followed what became the Delaware River valley from Trenton, New Jersey, then curved back across southern New Jersey’s interior. Waterways cut into the earlier marine sands of the local Cohansey Formation to lay down the fluvial deposits known as the Bridgeton Formation, thus building the county’s surface deposits. During the Ice Age windblown silt known as “loess” enriched the sandy-gravelly deposits of the Bridgeton Formation, which accounted for the increased productivity of soils found in the western part of the county and along the Delaware Bay.

Agricultural development of this prime farmland and timber harvest were the initial commercial enterprises. Products shipped to market by water. As early as the 1690s, the Cohansey sawmill of Richard Hancock (ca.1640-89), previously Fenwick’s surveyor general, supplied Philadelphia with cedar.

The Revolution Intervenes

The American Revolution interrupted Cumberland’s growing prosperity. The area suffered during Philadelphia’s occupation by the British during 1777-78, when it served as prime territory for foraging troops. Farmers were afraid to leave their houses to plow or sow crops, and the population faced an increasingly dire situation until the British evacuated Philadelphia in June 1778.

Shipbuilding began in 1780 when the schooner Governor Livingston was constructed at Bridgeton. Unfortunately, on her first homeward voyage, she was captured by a British frigate, discouraging further shipbuilding for another fifteen years, until John Lee (c. 1765-1840) established a shipyard in 1795 in what became Leesburg. Prior to a decline around World War II, 583 ships were built in Cumberland County, with Bridgeton (153 ships), Dorchester (100), and Leesburg (71) dominating the industry.

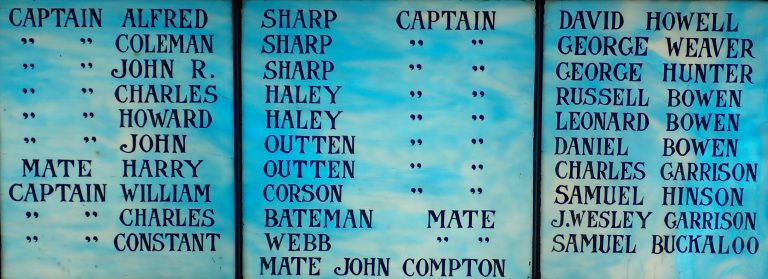

In another facet of maritime commerce, in the nineteenth century, schooners from the Maurice River plied the coastal trade, transporting goods up and down the East Coast from Nova Scotia to the West Indies and South America, and even to Europe. Mauricetown served as the home port for most of the captains, and their homes remained in what subsequently became the Mauricetown National Register Historic District.

Fishing and oystering made up the third aspect of maritime business. The Cumberland County shore and river mouths were ideal oyster habitat, which thrived in a mix of fresh and salty waters. The Lenape harvested oysters at low tide, and they became a food source for settlers in the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century, oysters became the nation’s fast food, and in Philadelphia were “sold by dozens and hundreds up to ten o’clock at night in the streets.” In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the national oyster harvest became centered on the Delaware Bay, and in particular the Maurice and Cohansey Rivers. By 1874, 372 oyster boats were listed in Cumberland County. Some of the oysters shipped by boat, but a direct railroad line to Bridgeton, the Cumberland and Maurice River Railroad (completed in 1875), offered an alternative form of transporting the oysters to market. At the height of the industry in the 1920s, seven thousand boxcars left Bivalve on the Maurice River alone, with 58,800 tons of oysters shipped in shell during 1923.

The tiny settlement of Caviar on the Delaware Bay in Greenwich Township briefly became the center of the world’s caviar production in the 1880s, after the sturgeon of Russia and Germany were fished almost to extinction. The industry was so profitable a new rail line, the New Jersey Southern Railroad, was built between Caviar and New York City. At the height of the fishing season, fifteen rail cars full of caviar left daily for the city, where most was sent on to Europe, including Russia. Overfishing decimated the Delaware Bay sturgeon population, which declined in the 1890s and crashed to almost nothing in 1900.

The county’s land-based economy transformed around the turn of the nineteenth century, when local entrepreneurs implemented developing hydropower technology by damming both the Cohansey and the Maurice Rivers. Earlier saw and grist mills had used more primitive forms of water power, but the new dams were intended to drive emergent industries. In Millville, Philadelphians Henry Drinker (1734-1809) and Joseph Smith formed the Union Company in 1790 to purchase twenty-four thousand acres in the eastern part of the county. Drinker and Smith built a dam and mills to use the waterpower. Five years later, they sold out to Joseph Buck (1753-1803) and partners, and Buck laid out the town of Millville, producing a plan that reserved the land bordering the river for mills, with residential areas on higher land away from the river.

R.D. Wood & Co.

David Cooper Wood (1781-1859) of Greenwich Township constructed an iron foundry and furnace in Millville in 1814, first manufacturing stoves and iron posts for gaslights and eventually specializing in water pipes. Thirty years later, with the foundry in trouble, David’s half-brother Richard Davis Wood (1799-1869) came to his aid; in 1850, he bought David out and formed R.D. Wood & Co. Richard expanded the available water power and diversified the industries, adding a cotton mill, a bleach and dye works, and a glass factory. The combined industries were managed in Philadelphia, eventually becoming R.D. Wood & Sons. In 1890 Richard’s son George (1842-1926) moved to Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and formed Wawa Dairy Farms as a hobby. The hobby became a business that began selling milk from its own stores in 1964, and in 1968 the two businesses merged as Wawa Inc. From 1971 until 2009, Wawa Inc.’s regional headquarters were located in David C. Wood’s 1814 house in Millville.

Bridgeton’s industrial development began in 1815, when brothers Benjamin (1779-1844) and David (1793-1871) Reeves of Deptford Township, great-grandsons of John Reeves (1674-1748), exclusive operator of the early eighteenth-century ferry between Burlington, New Jersey, and Philadelphia, purchased water power to operate the Cumberland Nail Works, which became Bridgeton’s major industry for the rest of the century.

Steam power had replaced water power by the time Oberlin Smith (1840-1926) left his job at Cumberland Nail and Iron and founded the Ferracute Machine Company in Bridgeton. He and his partners specialized early on in making can presses for local food processers. By the end of the century, Ferracute was shipping presses around the world, including an entire mint to China. At its height during World War II, Ferracute employed as many as seven hundred people. The automobile industry became the mainstay of the company, and Ford Motor Company was the major client until Ferracute closed in 1968.

The nineteenth century also saw the development of the glass industry. Cumberland was an ideal location because of the presence of weathered quartz sands of the Cohansey Formation, used in making glass. Also present were molding sands, aggregates of sand and clay, used for making cast-iron molds for the glass. The industry began as early as 1799, when James Lee (1771-1820) built a factory in Port Elizabeth. Lee moved his operation to Millville in 1806, but the Port Elizabeth factory survived under various owners through most of the nineteenth century. In 1838, John Whitall (1800-1877) of Philadelphia became a partner in Lee’s Millville factory in 1838 and was joined by his brother Israel Franklin Whitall (1795-1873) in 1845. The brothers continued to live in Philadelphia and run the company headquarters. The factory specialized in bottles, jars, and vials, many custom-made for Philadelphia pharmacies. Whitall, Brother & Company evolved into Whitall Tatum Company. After 1938 the business went through a series of owners until it closed in 1999, having survived for 193 years.

The first glass factory in Bridgeton, Stratton, Buck and Co., began operations in 1836. Eventually, the town supported twenty glass operations. Cumberland Glass Manufacturing, formed in 1880, evolved into Owens Illinois Inc., one of the largest glass manufactories in the country and Bridgeton’s major employer until it ceased operations in 1984. Owens Illinois closed the plant because the equipment was outdated, and the decreased need for glass containers in the era of plastic did not warrant the expense of modernization.

A Processing and Transportation Center

While Cumberland County as a whole prospered in the nineteenth century, and Bridgeton became the processing and transportation center for the agricultural products of the western side of the county, the poorer soil toward the northeast was left fallow and appropriated for open cattle range. Before the Civil War, the population in that area amounted to only about two hundred people. Charles K. Landis (1833-1900), born in Philadelphia and educated as a lawyer, had already participated in the founding of Hammonton, Atlantic County, New Jersey, when he purchased twenty thousand acres from Richard D. Wood in 1860; further acquisitions brought the total to about fifty-three thousand acres.

Landis, a liberal thinker who supported abolition and votes for women, planned a utopian agrarian community and hoped that Vineland would attract progressive thinkers as well as farmers and grape growers. To this end he banned alcoholic beverages from the start, which appealed to women in the suffragist movement, many of whom also promoted prohibition. He advertised nationally starting in 1861, and though some called him a charlatan for selling unproductive farmland, he had many buyers. Advances in agriculture meant that with much effort and investment, the poor soil could be made productive. In 1866 alone, over twelve hundred buildings were constructed, and by the end of the decade, there were over seven thousand residents.

Vineland soon became a center for the suffragist movement; during the 1868 election, women brought their own ballot box to the poll and proceeded to vote, knowing their votes would not be counted. From the beginning, Vinelanders were sensitive to the uniqueness of their community, and founded the Vineland Historical Society in 1864, when the city was just three years old.

To encourage the agricultural aspect of his community, Landis reached out to Italian grape growers, offering a twenty-acre property in exchange for building a house within a year, and clearing and cultivating the land for vineyards. In the 1860s and 1870s northern Italians moved to Vineland; in the 1870s and 1880s immigration shifted to southern Italy. Vineland continued to attract Italian immigrants up to the 1920s. The vineyards, orchards, and berry patches flourished, contributing to Vineland’s prosperity and Cumberland’s agricultural economy.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Cumberland County bay-shore became a vacation destination, supplementing the existing industrial, maritime and agricultural economy. A forty-room hotel, the Warner House, was built in 1877 at Sea Breeze, south of the mouth of the Cohansey, to accommodate Philadelphians leaving the Chestnut Street wharf on the steamer John A. Warner. The resort boasted a pier, a toboggan slide, a boardwalk and a bowling alley, and an occasional clam bake and yacht regatta. Attractions at East Point, near Heislerville, included a hotel and a tavern, and the Fortescue Hotel offered lodgings in Fortescue, a fishing resort between Sea Breeze and East Point along the bay shore. Railroad access from Philadelphia to the ocean resorts diminished the appeal of the bay destinations by the time of World War I, and Sea Breeze and Fortescue catered mainly to county residents after that.

Bird Hunting for Sport

Railbirding—hunting small waterfowl known as rail—appealed to wealthier Philadelphians. In order to pursue the sport, a few, such as the Wetherill family, owned houses along the Cohansey, and many were members of the Sora Gun Club. Probably the Cohansey’s most famous Philadelphia visitor was artist Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), who travelled regularly throughout the 1870s and 1880s to his family’s “fish house” in Fairfield Township. Eakins first came with his family and later brought his students with him. The Cohansey was the inspiration for some of his best-known works, including “Starting Out After Rail” (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and “Pushing for Rail” (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

In the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Cumberland’s economy continued to depend in large part on the three components of agriculture, maritime activities, and glass manufacturing. Agriculture, and the related industries of processing and distribution, were still the mainstay of the county’s economy. Founded near Bridgeton in 1933, Seabrook Farms Corporation was a national leader in the development of frozen foods, and in 1955 Life magazine called it “the greatest vegetable factory on Earth.” The tomato and asparagus fields in western Cumberland in the mid-twentieth century gave way, for the most part, to corn and soybeans. The original Seabrook Farms closed in 1976, but in 1978 grandsons of the founder, Charles F. Seabrook (1881-1964), built a new frozen vegetable processing plant in Upper Deerfield, freezing snap beans, spinach, collards, mustard greens, peppers, peas, and lima beans, 95 percent of which were grown within the county. In the twenty-first century, much of the farmland was bought or leased by nurseries, as rising land values in central New Jersey forced growers to seek less-expensive acreage. Around Vineland, farmers specialized in growing vegetables and herbs, particularly for ethnic cuisines.

Oystering reached its peak in the early twentieth century, but two parasites, commonly known as “MSX” and “Dermo,” devastated the oyster population and the industry at mid-century. Research in management of the parasites, conducted, in part, at Rutgers University’s Haskin Shellfish Laboratory in Bivalve, led to a slow but steady revival of the industry in the twenty-first century. Concurrently, the Bayshore Center, home of restored oyster schooner A. J. Meerwald, New Jersey’s official tall ship, celebrated and interpreted the industry.

In the late twentieth century, the glass industry declined as plastic supplanted glass for many uses. The loss of the major glass manufacturers—Owens Illinois in Bridgeton and Whitall Tatum and the major operations of Wheaton Glass in Millville—eliminated glassmaking as the county’s major industry but did not end it altogether. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, the glass industry employed close to three thousand people, with eight companies in operation. Most concentrated on specialized products for medicinal and laboratory needs, but the largest, Durand Glass, produced a variety of hollowware.

Cumberland County was fully engaged in national events in the first half of the twentieth century. Fortescue, on the Delaware Bay between the Cohansey and Maurice Rivers, was a focus of activity during Prohibition when it acted as a major port for landing whiskey brought to the three-mile international limit by ships from Canada and Jamaica. Tenders brought the liquor into the bay, and many local ship captains transported it to shore and hid it in the marshes until it could be transported north by truck. A light on the roof of the eight-story Cumberland Hotel in Bridgeton signaled when it was safe for the trucks to pass through town. Local residents, including law enforcement, were aware of what was going on, but kept silent out of sympathy, fear, or remuneration.

The Millville Airport, begun as a civilian airport in 1939, expanded to become an airfield capable of hosting fighter planes as World War II engulfed Europe. Leon Henderson (1895-1986), a Millville native serving as head of the U.S. Office of Price Administration, was instrumental in having the airfield dedicated as “America’s First Defense Airport” in August 1941. It opened as a gunnery school for fighter pilots in 1943. For most of the war, training was done on the P-47 Thunderbolt, with about 1,500 pilots passing through the program.

Tourism as a Supporting Industry

Tourism continued to be a major supporting industry. The New Jersey Motorsports Park opened on five hundred acres in Millville adjacent to the airport in 2008. It featured two road courses, a go-karting complex and other amenities, which attracted fans and participants from across the country. In 2010 the surviving World War II buildings at the Millville Airport became the Millville Army Air Field Historic District in the middle of the still active airport, and were home to the Millville Army Air Field Museum and ancillary attractions

Nonprofit arts and culture organizations generated increasingly significant revenue, over $16 million in 2015 alone. In 1994 Millville developed the downtown Glasstown Arts District, a public art center with galleries and studios. Also in Millville, Wheaton Arts, and the Creative Glass Center of America, founded as Wheaton Village in 1968, featured a museum with a major collection of early American glass and working glass artists in a recreated nineteenth-century glass factory. Beginning early in the twenty-first century, the restored Landis Theater in Vineland and the reconstructed Levoy Theater in Millville provided live musical performances, and the Off Broad Street Players Theater Company and the Cumberland Players contributed live theater. Bridgeton reemphasized its century-old 1,100-acre city park and its amenities, such as a children’s splash park, boating on Sunset Lake, and the 1934 Cohanzick Zoo, with over forty species. Vineland was home to the last remaining drive-in theater in the state and the reconstructed Palace of Depression, the 1932 original of which was advertised as “The Strangest House in the World.”

Each year, fishing competitions in Fortescue, the February Eagle Festival in Mauricetown, Bay Day at East Point Lighthouse, an eighteenth-century-style Craft Faire in Greenwich, the Wheaton Arts Festival of Fine Craft, the Millville Army Air Field Museum Air Show, and the Cumberland County Fair provided activities for residents and visitors. The county’s cultural diversity made an additional contribution through a series of annual events such as Seabrook’s Japanese Obon Festival, Vineland’s Puerto Rican and Greek festivals, Bridgeton’s Cinco De Mayo Celebration, and the Friends of India Kite Festival.

The Prison Industry

In the twenty-first century, four prisons were a major source of jobs in the county, with over two thousand employees among them. Cumberland County hosted Bayside State Prison in Leesburg, Southern State Correctional Facility in Delmont, and South Woods State Prison in Bridgeton. In 1990, Fairton Federal Correctional Institution, a medium security prison for men, opened. Inexpensive land attracted the state and federal governments to build the prisons, and the county acquiesced on the promise of jobs. Other major employers were health and human services organizations and government agencies.

As the twenty-first century progressed, the county faced a serious threat to its continuing existence. The close proximity to the Delaware Bay with its rising sea level, exacerbated by sinking land (technically known as glacial forebulge subsidence), endangered the survival of the bay-shore communities. Thompsons Beach, Moores Beach, Money Island, Seabreeze, and parts of Fortescue, once thriving villages along the Delaware Bay shore, were bought out by the state’s Blue Acres program (a fund for buying property subject to increased flooding to discourage further habitation) and the buildings bulldozed. With sea level predicted to rise by as much as six feet threatening to inundate up to a third of the county by the end of the century, the continued long-term existence of large portions of the area was uncertain.

The county maintained many historic connections and patterns in the twenty-first century, as development evolved at a slower rate than in other parts of the region. With a county per-capita income of $21,883 according to the 2010 census, the search continued for new, compatible industry. Growing cultural diversity made Cumberland a majority-minority county (one in which no racial group makes up more than half the population), the only one in the southern part of the state. Cumberland County kept its historic connection to agriculture by purchasing preservation easements on twenty thousand acres of farmland, one-third of the remaining total. It grew 20 percent of New Jersey’s produce and 28 percent of the state’s horticultural product, making it by far the most productive agricultural economy in the Garden State. Agriculture and related industries provided more than four thousand jobs. Glassmaking endured as a viable industry. Commercial oystering, fishing, and crabbing continued at a diminished level, as the rivers and bay were used primarily for recreation. The lack of explosive economic development was a trade-off that many residents were willing to accept in return for a less-congested and more community-oriented quality of life.

Penelope S. Watson, AIA, is a Principal at Watson & Henry Associates, where she has worked as preservation architect for over thirty years. She has an undergraduate degree from Mt. Holyoke College, a professional degree from the Boston Architectural College, and a Master’s in Preservation Studies from Boston University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History