New Sweden

Essay

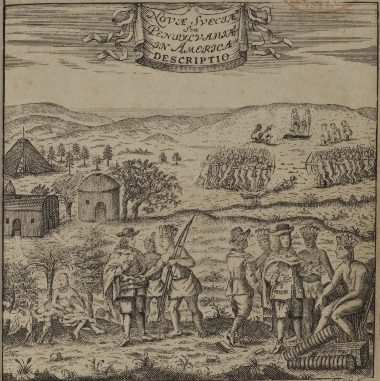

Founded in 1638, the colony of New Sweden survived less than twenty years and at its peak numbered only about four hundred people, most of whom lived along the western bank of the Delaware River between what became Philadelphia and New Castle, Delaware. As small and short-lived as it proved to be, New Sweden had important effects that persisted long after its conquest by Dutch forces in 1655. It was the first lasting European settlement in the Delaware Valley and transformed relationships between native peoples and Europeans. It also affected the process of European colonization in North America and had a decisive influence on the cultural development of the greater Philadelphia region.

The idea of planting a Swedish colony in the Delaware Valley came from Peter Minuit (c. 1585-1638), a native of the German city of Wesel on the Lower Rhine. Before becoming involved in the New Sweden venture, Minuit had served six years as the director of New Netherland, a colony established by the Dutch West India Company (WIC) in 1624. After being recalled for squabbling with New Netherland’s Reformed minister, Minuit sought out the patronage of Samuel Blommaert (1583-1654), a high official in the WIC who had entered the service of the Swedish government. Soon afterward Blommaert began pushing Minuit’s idea for a colony called Nova Sweediae. Eager to demonstrate its status as a great power in Europe, the Swedish government granted its approval and by early 1637 plans for the first voyage began to take shape.

New Sweden was designed to be a miniature copy of New Netherland, the Dutch colony centered on the Hudson River (later English New York). Like New Netherland, it would be a company-owned colony whose main goal was to make a profit by exchanging European-manufactured goods such as cloth, beads, tools, and weapons for furs and skins provided by Indian suppliers. The colony’s merchants would also purchase tobacco and other commodities from neighboring colonies for resale in Europe. New Sweden would have a small but significant agricultural base so that it could sustain itself and produce its own goods (including tobacco) for trade or sale.

Native Trading Partners

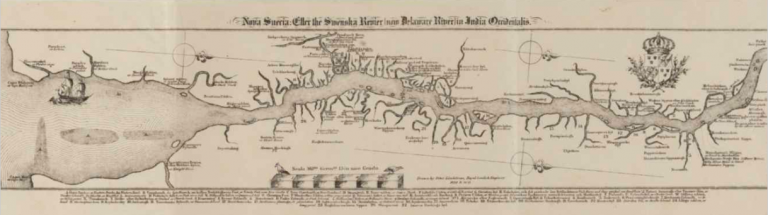

From the start, New Sweden depended for its success upon its relationships with neighboring native peoples. When Minuit and his small Swedish and Dutch crew sailed up the Delaware River for the first time in the spring of 1638, they made important agreements with several sachems belonging to the Lenapes and the Susquehannocks (or “Minquas”). The Lenapes, who numbered several thousand people at the time, occupied a string of independent communities along the river and were considered by all to be the owners of the lands adjoining it. The Susquehannocks lived farther west in the Susquehanna Valley, where they were just as populous. They were the region’s main fur suppliers and had staged destructive attacks on Lenape communities just a few years before. Both sets of peoples welcomed the Swedish colony as a new source of trade goods and a new source of power in their own relations with other Indians in northeastern North America.

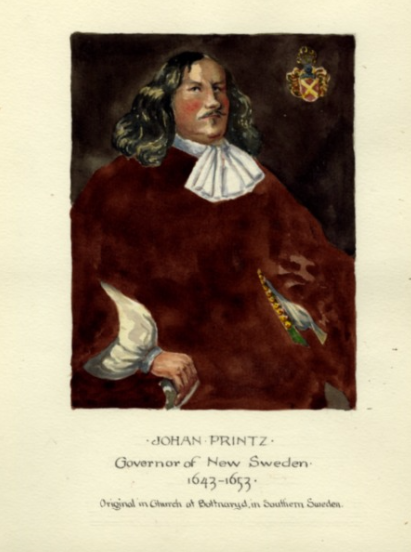

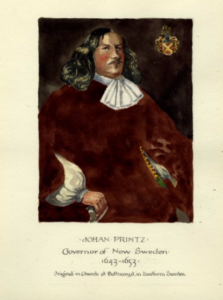

With the permission of the Lenape and Susquehannock sachems, Minuit’s men erected a small fort (Fort Christina) at the mouth of the “Minquas Kill” (Christina River in modern-day Wilmington, Delaware). Over the next decade, especially under its longest-serving governor, Johan Printz (1592-1663), the colony extended its reach by establishing small fortified trading posts and farming settlements on both sides of the lower Delaware Valley. The main purpose of New Sweden’s forts was to deter trade and settlement by its European rivals, especially the WIC, which asserted that New Netherland’s limits extended from the Delaware Bay to New England. However, it was only after Pieter Stuyvesant (1612-72) became director-general of New Netherland in 1647 that WIC officials began to press their claims more strongly. Although occasional groups of English colonizers also attempted to trade and plant along the river, arguing that the territory belonged to the English Crown, none was able to secure a permanent foothold.

During the 1640s New Sweden’s population grew to about two hundred people. Seven ships arrived from Sweden during that decade, bringing soldiers, company servants, a few dozen free settlers, and a handful of Lutheran priests. Most of the servants and freemen were single men but a few families came over, as well. Nearly all were Swedish or Finnish, although in the early years the colony included a small number of English and Dutch settlers, too. Recruiting free settlers proved to be very difficult for the Swedish government, and many of the colony’s inhabitants were sent there as a form of punishment. The flow of settlers stopped abruptly in 1648 and did not restart until six years later. After putting down a mutiny in 1653, Printz left for Sweden, joined by a group of settlers. A mass desertion seems to have followed once they departed. By the time a ship bearing new colonists and a new governor finally arrived in 1654, New Sweden’s population had dwindled to about 130 people. Supplemented by the new arrivals, the colony’s population rose to about four hundred. This sudden growth caused its own problems, especially in securing enough food for the newcomers.

Swedish Defenses Decline

During the early years of his governorship, Printz had overseen the construction of several new forts, the expansion of agricultural settlement, and successful participation in the fur trade. By the time he left, the colony had abandoned many of the peripheral forts and could no longer protect itself. Indeed, Printz had been powerless to prevent Stuyvesant from establishing a new fort (Fort Casimir, in contemporary New Castle, Delaware) just downriver from Fort Christina. The colony seemed to revive when Printz’s replacement, Johan Risingh (1617-72), arrived in 1654. His soldiers captured Fort Casimir (renaming it Fort Trefaldighet), and he and his officers confirmed the colony’s alliances with its Lenape and Susquehannock partners. New Sweden’s officers also promised the numerous freemen in the colony that they would finally be able to gain title to the company lands that they worked. These promises were not fulfilled. When WIC officials in Amsterdam learned Fort Casimir had been captured, they dispatched a heavily-armed warship and two hundred men to New Netherland expressly to conquer the Swedish colony. Within a year, Stuyvesant led a fleet to the Delaware River and forced New Sweden’s officers to surrender.

Risingh and 36 settlers, soldiers, and officials departed for Europe shortly after the fall of the colony, but most of New Sweden’s inhabitants stayed behind in the Delaware Valley, now under Dutch rule. They remained the majority of the European population along the river for the next quarter century. During this era they strengthened their close relationship with the Lenapes, whose population had been reduced by disease but still numbered in the thousands. After the English takeover of New Netherland in 1664 Swedes and Finns often served as mediators between English officials and the Lenapes. Other Europeans also came to rely on the Swedes and Finns for their knowledge of the land. Some scholars believe the iconic American log cabin may have been introduced to North America by so-called “Forest Finns” who had settled in New Sweden.

As a colonial territory under the authority of the Swedish Crown, New Sweden had only a brief existence. But the influence of Swedish and Finnish settlers in the Delaware Valley lasted much longer. Indeed, in the years after conquest, their community seemed to gain greater coherence as new arrivals and old settlers worked out a new form of collective identity under Dutch and then English rule. Even after English colonists began arriving by the thousands in the 1670s and 1680s, Swedes and Finns retained a distinctive place in the diverse Delaware Valley. Supported from afar by the Church of Sweden, their local Lutheran churches ensured that their linguistic and religious attachments survived well into the eighteenth century. A visible reminder of the colony’s original influence and lasting impact is the Gloria Dei Church, or Old Swedes’ Church, in South Philadelphia. Constructed during the last years of the seventeenth century, its religious services continued more than three hundred years later.

Mark L. Thompson is an American historian who teaches at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. His book The Contest for the Delaware Valley: Allegiance, Identity, and Empire in the Seventeenth Century (2013) won the Pennsylvania Historical Association’s Philip S. Klein Book Prize for the best book in Pennsylvania history in 2012-14. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Tall ships ply waters off Philadelphia for weekend Seaport Festival (WHYY, October 5, 2012)

- Swedish King and Queen to visit Delaware in May (WHYY, January 16, 2013)

- Wilmington mayor hosts Swedish dignitaries as Delaware prepares for royal visit [video] (WHYY, May 9, 2013)

- Swedish royalty celebrate 375 years of history in Delaware (WHYY, May 11, 2013)

- Old Swedes Church joins First State National Park [video] (WHYY, May 11, 2015)

Links

- The Search for Fort Casimir (Blogging Delaware History)

- Governor Prinz Park Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Tinicum Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory)

- New Sweden Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Charter of the Dutch West India Company: 1621 (Avalon Project at Yale School of Law)

- American Swedish Museum

- The Swedish Colonial Society