Southwest Philadelphia

Essay

Southwest Philadelphia, which along with adjacent Tinicum Township, Delaware County, is the location of the Philadelphia International Airport, greets many visitors to the city. Yet, Southwest Philadelphia, often described as “far” Southwest, is quite possibly the least-known area of the city, even to Philadelphians. Kingsessing, as this vicinity was originally named, was the first section of Philadelphia settled by Europeans and in the twentieth century came to national attention as the Eastwick Urban Renewal Project. Since the early twentieth century, when this seemingly remote location in the city became useful for an airport and other industrial activities, the possible contributions of Southwest Philadelphia to the metropolitan economy have often overshadowed the needs of neighborhood residents.

Southwest Philadelphia is the southern portion of the city lying west of the Schuylkill River. The northern boundary is roughly marked by Baltimore Avenue, Fiftieth and Forty-Ninth Streets; on the west by Cobbs and Darby Creeks, which separate Philadelphia and Delaware Counties; on the south by the Philadelphia International Airport, and on the east by the Schuylkill River. Southwest Philadelphia encompasses the city’s Fifty-First and Fortieth Wards and includes the neighborhoods of Kingsessing, Elmwood, Paschall, and Eastwick; below Seventy-Fourth Street, Eastwick is known to residents as “the Meadows.” Large nonresidential tracts are occupied by the Heinz wildlife preserve, the Philadelphia International Airport, industrial parks, the Southwest Sewage Treatment Plant, and, adjacent to the Schuylkill River, tank farms and oil refineries.

This landscape includes the lowest-lying land within the city, some of it below sea level. The southernmost portion was at one time crisscrossed by a network of creeks. Mud, Hog, Carpenter’s, Minquas (Mingo), Province (later State), and Boon’s Islands were some of the largest of the Schuylkill River delta islands indicated on early maps. These well-watered meadowlands produced luxuriant grass and weeds for grazing livestock and fertile soil for plowing without the arduous task of removing trees, explaining their attraction for early European farmers.

Europeans Arrivals

Kingsessing, from a Delaware Indian word most frequently translated as “a place where there is a bog meadow,” became the center of Swedish occupation in 1643 when Governor Johann Printz (1592-1663) moved the Swedish headquarters to big Tinicum Island. The Swedes built two forts in lower Kingsessing to control the final leg of the Great Minquas Trail (Island Avenue), used by the Susquahannock (Minquas) beaver traders traveling from the Susquehanna Valley to the Schuylkill River. The Dutch and then the English claimed this vicinity—and the valuable beaver trade. William Penn created the township of Kingsessing, corresponding approximately with the later Fortieth and Fifty-First Wards.

Upper Kingsessing provided a convenient link between Philadelphia and points south, while lower Kingsessing seemed more remote. In 1696, the King’s Highway (later Darby Road) was laid out from Gray’s Ferry (the Lower Ferry), becoming the main artery from Philadelphia to Baltimore and the southern colonies. During the Revolution, an extension through William Hamilton’s estate, the Woodlands, linked the road (renamed Woodland Avenue) with the Market Street Ferry. Penrose’s Ferry from lower Kingsessing to South Philadelphia was not established until 1742, when a pest house (quarantine hospital) was constructed on Fisher’s Island (renamed Province, then State Island) to isolate contagious diseases. This ferry was finally replaced with a bridge in 1853; the fourth bridge, constructed in 1949, was renamed the George C. Platt Bridge.

During the War for Independence, Mud Island, adjacent to Province Island, became the site of a significant battle in the Philadelphia Campaign. In November 1777, the British wrested control of the island’s Fort Mifflin from American defenders. The victory helped the British to secure the Delaware River, allowing supply ships to reach Philadelphia.

The imperial struggles punctuating the early history of Kingsessing gave way to a peaceful agricultural landscape of farms and country estates for the next century. Limited industrial development occurred in isolated pockets adjacent to throughways and the larger creeks. Cobbs Creek provided water power for the Passmore Textile Mill on Woodland Avenue. Paschalville, laid out in 1810, was inhabited by the mainly British immigrant mill workers. At mid-century, the entire township contained only about 1,800 residents. Just after the Civil War, the Angora Woolen Mill and a small village were established just below Baltimore Pike.

Slow-Growing Kingsessing

The 1854 Act of Consolidation incorporated Kingsessing Township as the Twenty-Seventh Ward of Philadelphia but made little difference: Kingsessing, as it was still called, remained the slowest-developing section of the city for several more decades. Even the Philadelphia Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad linking Philadelphia to Baltimore through Kingsessing prior to consolidation did little to foster growth. The rural landscape made accessible by the railroad did encourage sporting activities, though. In the 1860s, the Suffolk Park Race Track and Hotel, with races reported in the New York Times, was established adjacent to Bell Road Station, the sole station in southern Kingsessing. In the next decade, the Belmont Cricket Club was located in the northern part of the ward. The Pennsylvania Railroad had closed the Bell Road Station by the time investors began subdividing tracts below Seventy-Second Street in the 1880s.

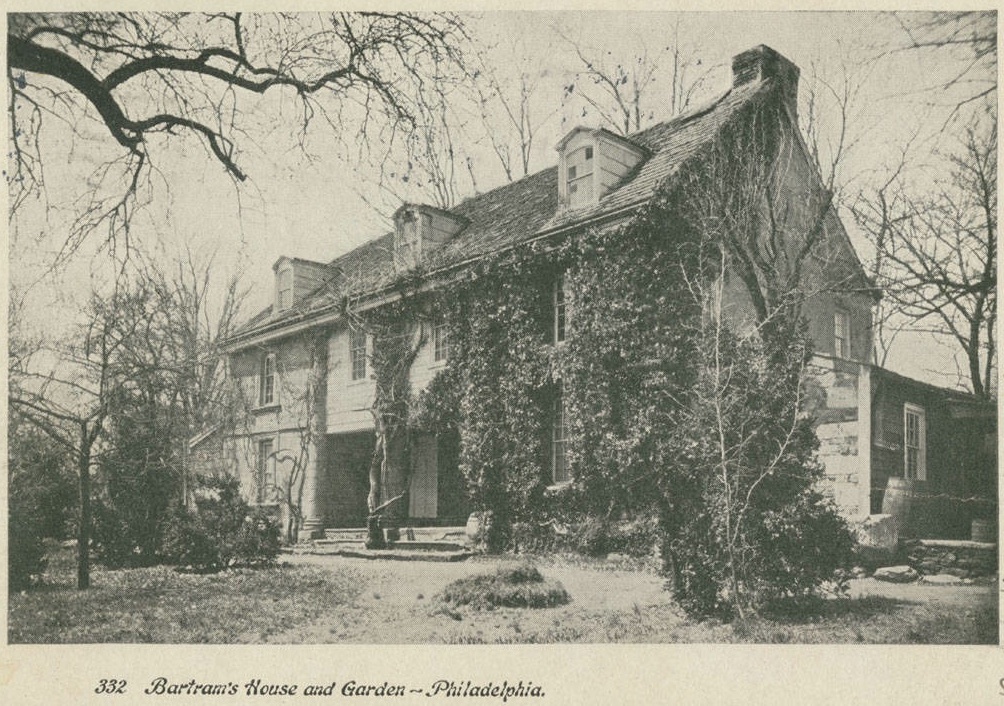

Perhaps Kingsessing is most important in American history for its famous garden nurseries and seed farms, which also benefited from the combination of a rural landscape and a railroad. Street names such as Botanic, Bartram, Dick’s, Lyon’s, and Buist commemorate this important local economy. In the eighteenth century, John Bartram (1699-1777) created what became the oldest surviving botanic garden in the United States. Railroad industrialist Andrew McCalla Eastwick (1811-1879) purchased the house and garden as a private park for his own country house, designed by Samuel Sloan.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Helendale Nurseries established by John Dick (1814-1903) included thirty greenhouses with more than 100,000 square feet of glass. The most famous Kingsessing nurseryman, Robert Buist (1805-1880), created one of the first great nurseries in the United States at Rosedale. Buist was the center of a trans-Atlantic horticultural exchange and is also credited with introducing the poinsettia to the United States from Mexico. One of his books, The Rose Manual (1844), was the first American gardening book devoted to roses.

This horticultural economy was made possible by the growing numbers of wealthy Americans who established country estates, as well as the rural cemetery and urban park movements. Mt. Moriah, located in Kingsessing and Yeadon, Delaware County, became the third of Philadelphia’s great cemeteries, along with Laurel Hill and the Woodlands.

Industries Move to Southwest

Southwest Philadelphia saw sustained residential and industrial development from the 1880s through the 1920s. Consequently, Ward 40 was made a separate ward before the turn of the century. In the 1890s, several important industries moved to Southwest. Joseph Fels built the Fels Naptha (laundry soap) factory on the site of the old Passmore mill. The J. G. Brill Company in Kingsessing and Baldwin Locomotive, which relocated from Spring Garden to adjacent Delaware County, both employed thousands of local residents.

Immigrant and native-born workers followed the opportunity for industrial employment. Irish, German, Lithuanian, Polish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants built detached and semidetached dwellings, often purchasing extra lots for large gardens. Once families located in the area, they tended to stay for generations. Below Seventy-Fouth Street, some truck and pig farms survived into the mid-twentieth century. The northern area just below Baltimore Pike developed in the first two decades of the twentieth century as home to native-born and northern European immigrants who worked in West Philadelphia or commuted to Center City. This more densely developed residential area was eventually separated from Ward 40 as the city’s Fifty-First Ward. As neighborhoods developed, trolley-served Woodland Avenue became an important retail district.

More dramatic changes were wrought by World War I, when the federal government authorized the American International Shipping Corporation to build Hog Island, the world’s largest shipyard. The site virtually became a town, with barracks to house almost 15,000 male workers. New railroad and trolley tracks transported an additional 20,000 workers and materials to and from the shipyard. The war initiated a significant demographic change: White and Black southern families found wartime an opportunity to move out of the South. In 1920, Black residents accounted for about 25 percent of the population of about 10,000 (excluding Hog Island dormitories) living below Seventy-Fourth Street at a time when Black residents accounted for about 27 percent of the total population of Philadelphia.

Greater Eastwick Improvement Association

The shipyard, closed in 1921, brought Southwest Philadelphia to the attention of City Hall in the competition for funding of transportation and municipal services. Real estate developer David E. Triester named the Fortieth Ward Eastwick and created the Greater Eastwick Improvement Association (GEIA) to obtain more comprehensive municipal services. Seeing the lesson of Hog Island, GEIA leaders, supported by the Southwest Globe Times, tied their future to the city when they successfully lobbied for a Southwest airport rather than a Northeast or Camden facility. Charles Lindbergh dedicated the new Southwest airport in 1927, but the muddy landscape proved challenging; for more than a decade the airport was moved to Camden. In the 1930s, Mayor S. Davis Wilson negotiated with the federal government for the Hog Island Shipyard site to bring the airport back to Southwest. Works Progress Administration workers filled in the area and built runways as part of Philadelphia’s share in the New Deal.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the GEIA less successfully and more controversially publicized the need for modern sewage systems and additional diking along the surviving network of creeks after several hurricanes seriously flooded homes and businesses. Some residents contended the association’s publicity created negative views of the area and discouraged investment in modern sewage facilities. Despite this, more residential development occurred in the 1920s than in the three previous decades. The 1920s building boom was so extensive that by the early 1930s sociologist William Weaver predicted the Tinicum Marsh would disappear. By that time, though, Philadelphia residents evicted from houses and apartments in other areas of the city erected shacks in the still largely undeveloped lower marshy areas.

After World War II, the Fortieth Ward once again gained public attention, some of which resulted in improved infrastructure—but not for longtime residents. In 1954, Philadelphia’s Mother of the Year, Jennie Harley Cook, was a homemaker from the Meadows (below Seventy-Fourth Street). Just a few years later, though, Harley and her family along with thousands of other Southwest families received eviction notices when Eastwick was condemned as a slum. Lack of modern sewage services and Depression-era shanties were featured in official city publications and city newspapers. The Philadelphia City Planning Commission had envisioned a “New Eastwick” to support the developing post-industrial service economy. In 1950, the Eastwick Urban Renewal Project began when much of Ward 40, about 3,000 acres, was declared “blighted.” Plans to reduce residential and farm use included creating space for an East Coast highway (I-95, which crosses the Schuylkill over the two-tiered Girard Point Bridge) and a hub of transportation and light industry centered on an enlarged international airport. The long-projected Southwest Sewage Treatment Plant was finally constructed as, despite residents’ protests, neighborhood demolition began in 1960.

Ongoing Challenges

Following the demolition, light industrial parks, shopping centers, and some replacement housing were built, but large tracts remained vacant. In 2002, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission certified a forty-block area of Kingsessing as “blighted.” Squatting and gap-tooth syndrome (empty lots between dwellings) had become common, and environmental problems continued to plague many residents, especially in the lower area. Despite the 1997 opening of SEPTA’s Eastwick Station and the relocation of Philadelphia’s main post office to Eastwick, in 2006 the entire Eastwick Urban Renewal Area was recertified as a blighted district.

In the decades at the turn of the twenty-first century, Southwest Philadelphia faced serious challenges to neighborhood stability, leaving high crime and vacancy rates in an area formerly characterized by high levels of home ownership and middle class apartment houses. Most Southwest neighborhoods experienced an overall decline in population after 1990, but they developed greater diversity—and racial tension—with an influx of new immigrant groups, primarily West African with some new Vietnamese and Hispanic residents.

The Elmwood neighborhood experienced some of the most serious racial tensions in the city in recent decades. This area was predominantly home to Polish and Irish American families centered on Roman Catholic parishes, but the disintegration of the manufacturing economy left many unemployed. In 1985, when two houses were sold to an African American family and an interracial couple, some white neighbors reacted violently, destroying property with axes and arson. Mayor Wilson Goode declared a state of emergency. Between 1990 and 2000 the white population of Elmwood decreased by almost 70 percent, while the African American population increased. Vietnamese and West African immigrants added to the racial picture. In 2008, John Bartram High School was placed in lockdown when a fight between African American and African students turned into a school riot.

Eastwick Stability

Eastwick, with a longer history of diversity, has not seen the dramatic population shifts of other neighborhoods, although by 2014 African American residents accounted for 76 percent of the residents. Eastwick residents have higher average education levels and homeownership rates than many other neighborhoods in Southwest, perhaps providing more economic and social stability for residents.

Eastwick residents, however, contend with worsening environmental justice issues compounded by episodic flooding, the consequences of incomplete redevelopment, and controversial plans for the future development of vacant areas. Environmental problems, always a challenge in this low-lying vicinity, have worsened with changing land use. Tinicum Marsh, once reduced to about 200 acres, was preserved by a 1972 Act of Congress because it contained the last remaining freshwater tidal marsh in the state. Renamed the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum, it encompasses 1,000 acres. But periodic flooding has increased since much of the vicinity was rezoned for industrial use. Large vacant tracts have attracted illegal dumping of hazardous substances that seep into the ground. Cleanup of former industrial sites has not always been conscientious. In the 1990s, environmental problems caused by nearby oil refineries led to a partly successful lawsuit for improvements to protect local residents. The airport expanded and became the cornerstone for planning development. Thus, the struggles of Southwest Philadelphians to achieve livable family neighborhoods continued in the early twenty-first century.

Neighborhoods in Southwest Philadelphia

Eastwick

Kingsessing

Elmwood

Paschall

The Meadows

Clearview

Penrose

Anne E. Krulikowski holds a Ph.D. in American history with a concentration in material culture/preservation from the University of Delaware. She teaches at West Chester University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Looking at SW Philly fire tragedy through the eyes of the city's Liberian community (WHYY, July 15, 2014)

- Liberian Women's Chorus for Change using music to heal in Southwest Philly (WHYY, July 17, 2014)

- PHL airport expansion to include extended runway, longer routes (WHYY, March 24, 2015)

- Reviving historic flower garden to help cultivate Philadelphia's connection with river (WHYY, July 14, 2016)

- New path for Eastwick opens up one year after termination of urban-renewal agreement (WHYY, December 28, 2016)

- Eastwick starts community-oriented planning process hoping to rewrite the history of urban renewal (WHYY, January 31, 2017)

- Bartram's Mile trail aims to connect Southwest Philly neighbors to river and city beyond (PlanPhilly via WHYY, April 21, 2017)