West Philadelphia

Essay

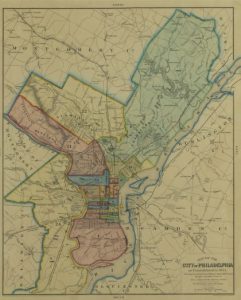

One of the single largest sectors of the city of Philadelphia at almost fifteen square miles between the Schuylkill River to the east and Delaware County to the west, West Philadelphia at its peak, in the early twentieth century, attracted an influx of new residents to its verdant, suburban-feeling neighborhoods. But over the course of the twentieth century, as the area became majority African American, it was hobbled by racist lending and employment practices. As a consequence, large swaths of the area became deteriorated and underpopulated, despite a vibrant Black political and cultural scene and, in the twenty-first century, a resurgent higher education and medical cluster.

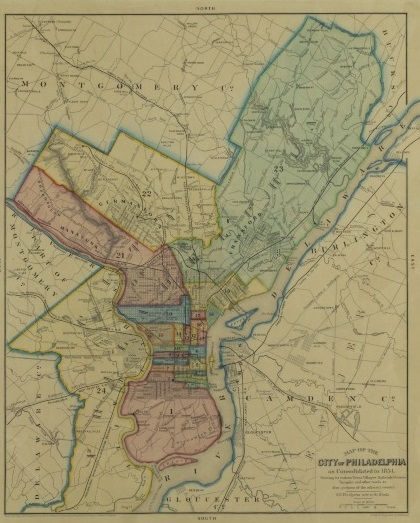

West Philadelphia did not exist until the middle of the nineteenth century. Although this part of the region witnessed small settlements of Lenape and Swedes who established Lutheran churches and log cabins on the west side of the Schuylkill, it was not included in the original plan of Philadelphia. William Penn wrote that the area “is likely to be a great part of the settlement of this age” and intended to expand settlement across the river. But he abandoned the idea by 1684, two years after his arrival.

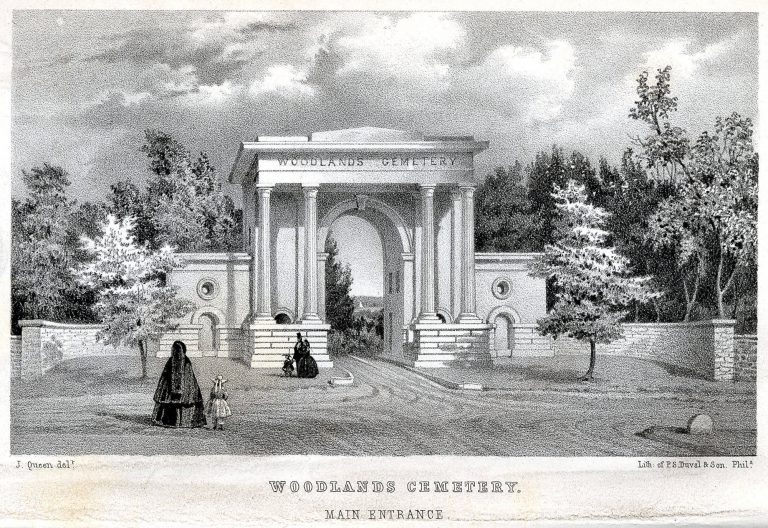

Throughout the eighteenth century much of what would become West Philadelphia remained sparsely populated farmland. Then on the far bank of the Schuylkill, port and mercantile infrastructure began to build up at this westward point of entry to the city. A major wagon route, Lancaster Pike, ran through the area, and in 1805 the first permanent bridge was built over the Schuylkill at Market Street. The Darby Road also ran up to this point, granting access to communities like Chester farther down the Delaware River. A few large estates were built during this time as well, most notably the Hamilton family’s Woodlands with its iconic Georgian mansion and that of John Bartram (1699-1777), the renowned botanist and Quaker who cultivated extensive gardens along the banks of the Schuylkill.

Bridge Promotes Growth

The new bridge spurred growth, prompting a network of industries, including stockyards, lumber mills, slaughterhouses, coal yards, foundries, and glass factories to serve the city across the river. Small communities began to spring up to support these businesses, like Hamiltonville in 1804. The then-scion of the family, William Hamilton (1745-1813), established the estate’s Georgian mansion and laid out

Hamiltonville as a continuation of Penn’s grid in Philadelphia proper. Other settlements followed, including Mantua Village, carved from the holdings of a local landowner, Judge Richard Peters (1743-1828), and laid out in 1809. Neither area proved popular at first, but as the city became more highly developed the lots began to sell. By the 1840s developers in Philadelphia, which was the second-largest city in the United States at the time, were already looking beyond the Schuylkill for fresh land. Abraham Brower’s innovative omnibus service, introduced to Philadelphia in 1831, allowed new settlers speedy access into the central city. At the time, the majority of residents were working class—about half immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and England—and settlements of any density tapered off at what would become the boundaries of Fortieth Street, with the wealthy clustered along Walnut and Chestnut near this westward extremis.

To accommodate the bourgeoning population, in 1844 Hamiltonville, Mantua, and Powelton joined together to incorporate as the borough of West Philadelphia, before being brought into the city proper with the consolidation of 1854. After that, the population exploded from eleven thousand in 1850 to twenty-three thousand in 1860. For the next half century at least, West Philadelphia largely became a suburb in the city—abetted by a series of advances in transportation technology, starting with the horsecars of the 1850s.

A bustling light industrial sector continued to grow south of Market Street on land adjacent to the river, relying on the Pennsylvania Railroad’s infrastructure around 30th Street Station to convey the sector’s goods efficiently. Some of the largest concerns included the metal workings at Job T. Pugh’s Auger Works, the Otto Gas Engine Manufacturing Company, and the Allison & Sons Car & Tube Works, one of the biggest wagon firms in the nation until its destruction by fire in 1872. Like the rest of the city’s manufacturing sector, West Philadelphia’s industry enjoyed great diversity. Everything from printers and bakeries to slaughterhouses and mirror manufacturers dotted this slice of the landscape.

Residential at First

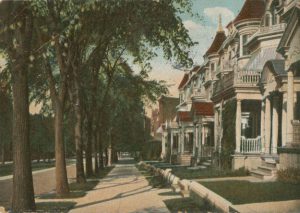

Despite the industry clustered along the area’s shores, development in this period remained largely residential in the rest of West Philadelphia. This set the living pattern apart from its counterparts in North and South Philadelphia, where row houses were interspersed with factories and warehouses. On the far side of the Schuylkill, the new housing developments were mostly marketed for the middle and upper classes, whose westward movement was further enabled by the replacement of the omnibus by horse cars in 1858. New routes into the city aided this movement too, like the Chestnut Street bridge completed in 1866.

Then in the 1870s the University of Pennsylvania left its cramped center city location for West Philadelphia, a move with enormous effect on the development of surrounding neighborhoods, especially during the second half of the twentieth century. After 1880 the larger houses closer to the river and the university, which dated to earlier in the century, began to be carved into smaller units. Apartment buildings—unusual in this row-house-dominated city—began to spring up as well. At the same time, new development moved beyond Forty-Fifth Street out to Cobb’s Creek, the border with Delaware County.

The introduction of electric streetcars in the 1890s further altered the area, as those with more resources moved farther out, leaving behind a more broadly based middle class. This process accelerated with the full extension of the Market-Frankford line in 1907, which boosted settlement, including that of immigrant and Black laborers living close to the line. By the twentieth century many of the wealthy residents who remained in West Philadelphia located away from the Market-Frankford elevated line or the multiplicity of trolley lines, further accelerating the growth of the Main Line suburbs in the process.

The district still had fewer than a hundred thousand people in 1890, but every new census revealed meteoric growth. In 1900 West Philadelphia had 148,548 residents, in 1910 the number grew to 247,928, and by 1920 there were 359,601. In 1923 the Philadelphia Bulletin estimated that at least half the population of the district commuted in to center city every day. Housing was at a premium, and due to the desirability of the area, the newspaper of record noted that more than any other section of the city, West Philadelphia encouraged the construction of apartment buildings and the subdivision of old mansions to accommodate the boom.

Soaring Ambitions

By the 1930s one of the more notable developments in West Philadelphia was the growing number of Black residents and the discriminatory pressures that boxed them into an intensely segregated area stretching south to Market Street, west to Fifty-Ninth Street, and bounded to the north and east by the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the river beyond it.

The process began during World War I, as Black migrants arrived in the city in increasing numbers. By the end of the 1920s, 220,000 African Americans lived in Philadelphia, and they desperately needed housing beyond the older Black ghetto in North Philadelphia. By the 1940s, the new area of settlement stretched from the river out to Fifty-Ninth Street and housed about forty-four thousand African Americans, from poor and working class by the water to the Black elite in the northwestern neighborhoods closest to the Main Line.

The Black population swelled again during World War II, breaking West Philadelphia’s racial boundaries by moving south of Market Street and west of Fifty-Ninth Street. As African Americans began living in more neighborhoods, the white population began fleeing to the expanding suburbs. By 1950, West Philadelphia had lost a quarter of its Irish-American and 11 percent of its Italian-American population, while the African American population increased by 72 percent. As the century wore on, the only corners of West Philadelphia that were not overwhelmingly Black were immediately around Drexel and Pennsylvania universities and in a band of neighborhoods to the west of the higher education cluster that remained racially mixed from the 1960s onward.

The Black residents of West Philadelphia were forced to contend with redlining and other discriminatory practices that limited access to capital and higher-paid employment for many residents. They were also discouraged, by legal means or by violence, from immediately following the white population into the growing suburbs. But during the early decades of majority-Black West Philadelphia, these challenges were attenuated by the growth of African American political power and the slowly declining, but still available, unionized industrial jobs.

Public sector employment in city government and the school district offered a wide range of employment opportunities for Black workers, from professional positions as managers and teachers to jobs that required less formal education, like sanitation and transportation. Many public sector unions became majority African American, or at least enjoyed large minorities of Black members, giving their neighborhoods larger political and economic anchors.

University Master Plan

As West Philadelphia became majority African American, the University of Pennsylvania began an ambitious expansion framed by its 1948 master plan (the university’s first update in almost half a century). A few African American neighborhoods close to campus were largely destroyed by eminent domain as a result, most famously the area known as Black Bottom that stood between the university and Powelton Village. The Black neighborhoods closest to the river, and therefore closest to Penn, tended to be those with the lowest income and the least political power. Farther west, African American neighborhoods tended to be more stable, with larger populations of public sector workers and private sector white collar workers, but that was little comfort to the displaced residents of Black Bottom.

The impetus for Penn’s expansion came from an infusion of government research funding along with the urban renewal dollars made available by the national Housing Act of 1949. During this period, the university adopted the moniker “University City” for the surrounding neighborhoods. Penn took full advantage of postwar federal largesse, competing successfully with its counterparts in higher education for research and development grants—especially after the flood of funding following the Soviet Union’s Sputnik success in 1957. Penn also competed with other parts of the city for urban renewal funds (much of the money allocated within West Philadelphia went to the university’s ends). The upgrades to campus were impressive. They were also necessary to create a more walkable environment and additional housing for a growing student body. But the expansion into surrounding residential neighborhoods embittered many residents.

In the latter decades of the twentieth century West Philadelphia kept changing as the white population continued to drain out of the city. The remaining African American neighborhoods continued to suffer discrimination in access to jobs and capital while many of the jobs that previously fostered economic stability were lost or undercut by the flight of manufacturing firms. This postindustrial economic vise resulted in the kind of divestment and shadow economy dealings that blighted many other inner city neighborhoods. In the 1980s some immigrants began to move into the area, chiefly African and Cambodian, although the latter population would almost entirely decamp for other parts of the city by the beginning of the twenty-first century.

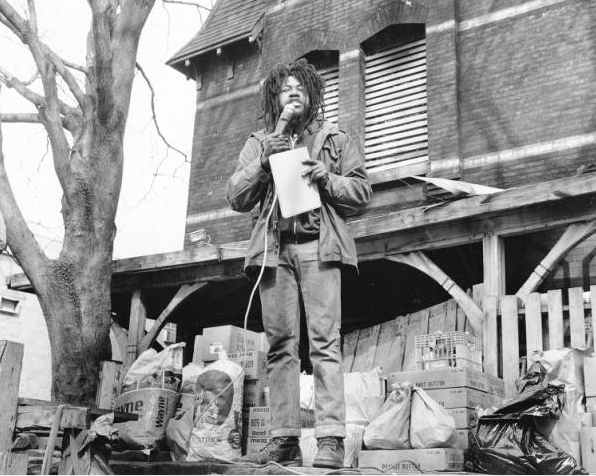

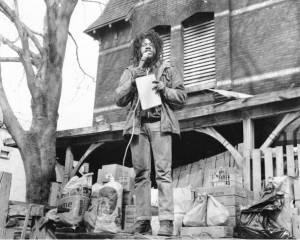

In the mid-1980s, crack cocaine reached West Philadelphia and wreaked havoc in many neighborhoods, resulting in a crime wave that scared off many middle-class African Americans and some of the remaining white families as well. The police department made matters worse by becoming the first U.S. law enforcement institution to bomb its own city. During a confrontation at the fortified compound of the anarcho-primitivist group MOVE in 1985, the police attempted to drop a high explosive on a bunker atop the radicals’ home. The resulting explosion sparked a conflagration that consumed much of the block and killed eleven people. In the following decade, farther to the east, general violence continued to rise, as it did in the rest of the country. After several high-profile murders of Penn graduate students living in the mixed- race neighborhoods beyond the campus borders, which had lost much of their white population during the 1990s, the university began to again be active in the community.

Under the guidance of university president Judith Rodin (b. 1944), who was born and raised in West Philadelphia, Penn promised to not repeat the aggressive steps taken in the 1950s and 1960s. Instead, it provided unarmed security services to patrol the area and exercised soft power to provide incentives to staff, from professors to janitors, to buy and repair homes in a catchment area around the university. Penn also invested in local public schools, founding the Sadie Alexander School, for pre-K through eighth grade. With other anchor institutions in the area, it supported development of the University City District to provide further amenities.

This activity resulted in the rejuvenation of the neighborhoods surrounding the university and the historically mixed-race neighborhood to its immediate west, which in 2010 became majority white for the first time since 1970. The university was not the only force at work; its efforts were aided by a nationwide decline in crime and marginal increase in the desire for urban living among a segment of the professional classes. Meanwhile, in many neighborhoods on the border of Delaware County and elsewhere, conditions worsened during the Great Recession and the subsequent decimation of the public sector workforce.

By the early twenty-first century West Philadelphia was about as populous as it had been in 1910, having lost more than a hundred thousand residents after 1950. It stood divided, like much of the city and the country, between the haves and the have nots. Its western majority African American neighborhoods were declining in population and median income. Much of the vacancy and crime that blighted West Philadelphia could be found in these areas, which were still cut off from legitimate employment and capital markets. This situation was counterpoised by the rise of University City, which was quickly becoming a rival for Center City in term of jobs and investment. It remained to be seen whether the ascendancy of the eastern section of West Philadelphia, where old industries and worker housing were giving way to new investment, would be enough to buoy the fortunes of the outlying, formerly middle class areas.

Jake Blumgart is a reporter for WHYY’s PlanPhilly. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Community leaders to unveil plans for a new West Philadelphia bicycle track (WHYY, May 5, 2012)

- Taking refuge in West Philadelphia's Clark Park (WHYY, July 26, 2012)

- Store front church a safe haven for kids in West Philly neighborhood (WHYY, August 3, 2013)

- Why parts of West Philly not getting the boost from attracting artists (WHYY, August 29, 2014)

- Philly Love Note: The 'Love Letters' of West Philly's El riders (WHYY, September 4, 2014)

- HUD chief tours West Philly 'Promise Zone' (WHYY, September 5, 2014)

- University City Science Center plans expansion that will double its size (WHYY, June 2, 2015)

- Area near Drexel in West Philly wins big school grant (WHYY, December 22, 2016)

- Historical marker coming to site of MOVE debacle (WHYY, March 31, 2017)

- New mural to honor Philly native Ed Bradley of '60 Minutes' (WHYY, May 3, 2017)

Links

- West Philadelphia Community History Center (University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center)

- West Philadelphia History Map

- West Philadelphia Italianate (PhillyHistory Blog)

- West Philadelphia: A Suburb in a City (PhillyHistory Blog)

- An Iron Baron's West Philadelphia Castle (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Decidedly Different West Philadelphia Twins (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- New Apartments, Old Glory in West Philadelphia (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- A Place for Enlightenment in Southwest Philadelphia (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- West Philly Home Still Sings the Praises of Paul Robeson (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: 4228 Walnut Street: Masjid al-Jamia (Historical Society of Philadelphia)

- I'm From Philly. 30 Years Later, I'm Still Trying To Make Sense Of The MOVE Bombing (National Public Radio)

- PhilaPlace: Association of Islamic Charitable Projects (AICP) — An Interview with Linda Hauber (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)