Cradle of Liberty

By Gary B. Nash

Essay

Philadelphians snort at the idea that a building in Boston—Faneuil Hall, a marketplace and meeting place–should presume to be called “the cradle of liberty” just because James Otis gave a fiery anti-British speech there in 1761. How can that compare to a city where the Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the United States were drafted, debated, revised, and signed—both in a brief period of eleven years?

Pride of place, if we can be generous for a moment, can be shared. Mark Twain once called Switzerland the Cradle of Liberty because alpine-born democracy had roots there too. Indeed the world is full of cradles of liberty, and some are now being violently rocked by young people hooked into social media as the Arab Spring turns the Middle East upside down.

Yet, Philadelphia is a special cradle of liberty.

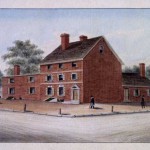

It not only was where the Continental Congress and Constitutional Convention did their epic work. Indeed, a century and more before, it was the city imagined by the visionary William Penn as a place where people of all classes, cultures, and ancestral backgrounds would learn to live together. Penn and his Quaker followers were determined to establish a unique colony free of the violence, intolerance, and corruption that were widespread on both sides of the Atlantic. Just a generation before, Puritans in Massachusetts were hanging Quakers on the Boston Common, and only a few years before Penn arrived they were bent on eradicating Wampanoag people from the Bay Colony

Religious and Ethnic Tolerance

Philadelphia—to be called the “city of brotherly love”—never entirely lived up to its visionary founding principles; but nowhere else in the hemisphere did colonizing Europeans display such substantial toleration for religious and ethnic differences and such peaceful relations with Native Americans. “I deplore two principles in religion,” Penn wrote memorably; “obedience upon authority without conviction and destroying them that differ with me for Christ’s sake.” Most European visitors were astounded at such words and at how they took hold.

For a while, Penn’s vision of “putting the power in the people” was realized in good measure. And then, nearly a century after Penn’s arrival, Philadelphia was the place where those stirring words that ricocheted around the world—“inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” and “we the people”—were written and enshrined. For generations to come, a storm of strangers would cherish Philadelphia as the place where these founding documents were written and ratified.

But many of the strangers came unfree and involuntarily. From Africa, they would wait a long time before they saw Philadelphia as a cradle of liberty. But they insisted that liberty should be theirs as well and were not shy about invoking the principles espoused in the nation’s founding documents. “Search the legends of tyranny and find no precedent.” thundered James Forten, accomplished sailmaker, businessman, church leader, and philanthropist, in 1813. “It has been left for Pennsylvania to raise her ponderous arm against the liberties of the black, whose greatest boast has been that he resided in a state where civil liberty and sacred justice were administered alike to all.” Shaking the cradle of liberty, he warned, in his effort to ward off vicious laws restricting free black men and women, that “the story will fly from the north to the south, and the advocates of slavery, the traders in human blood, will smile contemptuously at the once boasted moderation and humanity of Pennsylvania.”

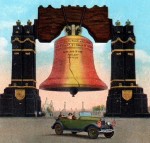

Two decades later, when “the cradle of liberty” motto was gaining currency, abolitionists in Boston and New York, seizing on the words from Leviticus inscribed on the brim of Philadelphia’s old State House bell, “Proclaim liberty throughout the land to all the inhabitants thereof.” Rechristening the bell as “the Liberty Bell,” they shamed Philadelphia for lagging behind in the crusade to cleanse the nation of its deep-dyed sin of chattel bondage.

Clash of Liberty and Slavery

This put Philadelphia on the defensive, its cradle of liberty motto under attack. “Shame on you,” shouted one abolitionist pamphlet with the Liberty Bell on its cover. “Is it to be tyrants amid slaves that Americans, with liberty glowing on every page of their history, and the glorious Declaration of Independence upon their lips, have been found willing to degrade themselves?” Another charged: “Hitherto, the bell has not obeyed he inscription: and its peals have been a mockery, while one sixth of all inhabitants are in abject slavery.”

And with that, the bell tarnished, the cradle of liberty needed repairs. That came as Philadelphians of different political persuasions paraded their own brand of liberty—Protestant nativists who put the Liberty Bell on a pedestal, literally, in Independence Hall in 1855 while attacking Catholics; pro-labor advocates such as the wildly popular journalist George Lippard, who fought to protect blue collar liberty from exploitative capitalists; and black Philadelphians struggling for social justice and the right to vote. In a fast-growing, immigrant-filled city many wanted to claim part of the cradle.

In time, the city cemented its claim as the cradle of liberty. The millions who thronged to celebrate the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in1876 had plenty of encouragement in reaffirming that Penn’s green country town was the cradle of liberty. Ownership of the cradle was strengthened as surging crowds paraded down Broad Street for the centennial of the Constitutional Convention in 1887.

Then into the twentieth century people of all political persuasions came to Philadelphia to embrace the Liberty Bell as the preeminent talisman of freedom. Among them were women suffragists during the Great War for whom the “cradle of liberty” terminology was dishonestly used while women were denied the suffrage.

Ideals vs. Realities

Similarly, when he was working to establish a National Freedom Day on which Americans could annually measure the distance between the nation’s glittering ideals and the somber realities on the ground, Richard R. Wright Sr., who had been born in slavery, knew just where to come. By laying a wreath in 1942 at the feet of the Liberty Bell, he furthered the notion of mending a splintered cradle of liberty. Civil rights activists repeated this ritual in the 1960s and 1970s by conducting sit-ins and demonstrations at Independence Hall

After World War II, leaders from newly independent countries—David Ben Gurion from Israel, Jomo Kenyetta from Kenya, a Ghanaian delegation, and many others—came not to New York or Boston but to Philadelphia, where they stood in Independence Hall and before the Liberty Bell to honor freedom’s birthplace that inspired their own quests for freedom. Cold War statesmen followed: Albert Tarchiani, the Italian ambassador to the U.S. in 1948; Ernst Reuter, mayor West Berlin, and Mohammed Mossedeq, premier of Iran, in 1951; Clement Atllee, prime minister of England in 1952; Nicholas Kallay and Mario Scelba, premiers of Hungary and Italy respectively in 1955.

The stream of international figures coming to pay their respects to Philadelphia as the cradle of liberty continues to the present day as they partake in the city’s historic role in building the nation. Yet the cradle still has cracks and blemishes. Perfecting it and keeping it in good repair requires an ongoing commitment to shoulder the responsibility of living up to the motto. This is the work of citizens, organizations, institutions, and politicians. Boasting about Philadelphia as the cradle of liberty is one thing; cradling liberty is another.

Gary B. Nash is Professor of History Emeritus at UCLA and the author of many books, including First City: Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.

Related Topics: Freedom, Revolutions, and Social Justice

Time Periods

Essays

- Gray Panthers

- Occupy Philadelphia

- Lawnside, New Jersey

- 1776

- Underground Railroad

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (The)

- Mennonites

- Black Power

- Liberty County

- Cold War

- Nativism

- Civil Rights (African American)

- Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

- Scots Irish (Scotch Irish)

- Woman Suffrage

- Freedom Train

- Whig Party

- Free Black Communities

- Crowds (Colonial and Revolution Eras)

- Militia

- General Trades Union Strike (1835)

- Greek War for Independence

- United States Colored Troops

- Reminder Days

- Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges

- British Occupation of Philadelphia

- Trade Unions (1820s and 1830s)

- Artisans

- Privateering

- Presidents of the United States (Presence in Region)

- Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

- Loyalists

- Civil Rights (LGBT)

- Price of a Child (The)

- Fugitives From Slavery

- Lafayette’s Tour

- Tourism

- Grand Federal Procession

- Dewey’s Lunch Counter Sit-In

- Vagrancy

- Alien and Sedition Acts

- Articles of Confederation

- Vigilance Committees

- Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) Strike

- Law and Lawyers

- Philadelphia Lawyer

- Revolutionary Crisis (American Revolution)

- Philadelphia (Warship)

- U.S. Presidency (1790-1800)

- Meschianza

- Martin Luther King Jr. Day

- Eastern State Penitentiary

- Christiana Riot Trial

- Modern Chivalry: Containing the Adventures of Captain John Farrago, and Teague O’Regan, his Servant

- Fries Rebellion

- Common Sense

- Whiskey Rebellion Trials

- Philadelphia Campaign

- Constitutional Convention of 1787

- Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens

- Capital of the United States (Selection of Philadelphia)

- Forts and Fortifications

- Murder of Octavius Catto

- Seven Years’ War

- Trenton and Princeton Campaign (Washington’s Crossing)

- U.S. Congress (1790-1800)

- National Colored Convention Movement

- Gayborhood

- Fort Wilson

- Valley Forge

- Philadelphia Plan

- Sullivan Principles

- Knights of Labor

- Haitian Revolution

- Bicentennial (1976)

- Animal Protection

- American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

- Political Parties (Origins, 1790s)

- Centennial Exhibition (1876)

- Pennhurst State School and Hospital

- Ladies Association of Philadelphia

- Slavery and the Slave Trade

- Abolitionism

- Spanish-American Revolutions

- French Revolution

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition (1913)

- National Freedom Day

- Constitution Commemorations

- Continental Congresses

- Declaration of Independence

- Sesquicentennial International Exposition (1926)

- Girard College

- Independence National Historical Park

- Independence Hall

- Liberty Bell

- Mother Bethel AME Church: Congregation and Community

- Women’s Education

- Salt Making

- National Constitution Center

- Museum of the American Revolution

- U.S. Supreme Court

- Civil Rights (Persons With Disabilities)

- Black Lives Matter

- Jews and Judaism

- Civil Rights (Women)

- Indentured Servitude

- Atlantic World

Artifacts

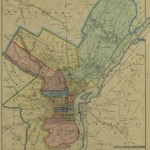

Map

Lawnside, New Jersey, has been one of only a handful of jurisdictions in the United States that has maintained a primarily African American population throughout its existence.

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Over eighteen years, from 1771 until his death, Benjamin Franklin composed his autobiography. His legacy is immortalized at the Benjamin Franklin Museum in Center City.

German Mennonites were among the first settlers in Philadelphia in the early 1680s. The 1770 Germantown Meetinghouse remains open as a museum and historic site.

The Black Power movement came to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s. From a storefront headquarters, the Philadelphia Black Panther Party distributed free lunches and information about the organization.

The Northeast Municipal Services Center, relocated from Roosevelt Boulevard and Welsh Road in 2016, was opened in 1985 by Mayor Wilson Goode. The Center was Goode's way of addressing the concern of Northeast Philadelphia residents that felt resources were being focused in other parts of the city and municipal services.

Civil Rights (African American)

Black Philadelphians have fought for civil rights since the nineteenth century and even before. In 1966, demonstrations led to the desegregation of Girard College, established in 1848 as a school for poor, white orphan boys.

Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

Philadelphia's connections to the Pacific World are as old as the city itself, including early participation in the China Trade and the first Japanese gardens in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition.

Presbyterian minister William Tennent founded this school in 1726 to train evangelically minded clergy. Critics mocked Tennent for attempting to educate poor country boys, derisively referring to his academy as the “Log College.”

Mill-Rae was the home of Philadelphia suffragist Rachel Foster Avery and a meeting place for activists in the early twentieth century. Serving as Cranalieth Spiritual Center since 1996, the home also is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Carrying artifacts and documents of American History, the Freedom Train left from Broad Street Station on a journey to unify the American people against the encroaching threat of communism.

The Whigs, the opposition party to Andrew Jackson and the Democrats during the antebellum era, gave Zachary Taylor their nomination for President at the Chinese Museum, located here in 1848.

Mother Bethel church in Philadelphia is the oldest AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church in the United States. Churches were staples for black communities and continue to hold places of leadership.

Crowds (Colonial and Revolution Eras)

Ordinary people helped shape the political culture by engaging in public celebrations, civil disorder, and, occasionally, collective violence. Crowds in the State House yard, for instance, heard and cheered the Declaration of Independence.

General Trades Union Strike (1835)

The General Trades Union Strike of 1835 was the nation's first general strike, prompted by coal heavers working along the Schuylkill River and demanding a ten-hour day.

During the Greek War for Independence (1821-28), Philadelphians helped arouse public sentiment in favor of the Greeks and raised money and provisions to aid the cause. The Second Bank was modeled on the Parthenon of Athens.

Over 10,000 African Americans from the Philadelphia area enlisted in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War and trained at Camp William Penn. Some earned the highest military accolades for their service.

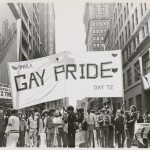

The annual Reminder Days demonstration at Independence Hall predated the Stonewall riots and stand among the first gay rights demonstrations in the United States.

Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges

In 1701 before William Penn left Pennsylvania for the last time, he granted the Charter of Privileges which granted the legislature the ability to govern itself. Pennsbury Manor was Penn's home in Pennsylvania.

British Occupation of Philadelphia

On September 26, 1777, the British army marched into Philadelphia, beginning an occupation that lasted until the following spring. For nearly seven weeks, British resupply was impeded by Fort Mifflin on the Delaware.

Philadelphians organized trade unions and supported one of the most successful labor demonstrations in the antebellum period, the General Strike of 1835. Soon after the strike began, protesters filled the Merchants' Exchange on Walnut Street.

Philadelphia's large port made it a hotbed for privateering, the legal capture of enemy ships by private citizens. This career could be lucrative and some privateers built large estates with their earnings.

Presidents of the United States (Connections to Region)

U.S. presidents have long visited Philadelphia to invoke the historic values of the country's founding documents. Independence Hall has been the backdrop for many such visits, beginning in 1833 with Andrew Jackson.

Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

Military veterans began organizing during the waning days of the Revolutionary War and continued to form organizations such as the Philadelphia Veterans Advisory Commission, established in 1957 and located in City Hall.

From 1965 through 1969, activists marched for gay rights each July Fourth in front of Independence Hall on July fourth. A historical marker at Sixth and Chestnut Streets commemorates the demonstrations, which became known as Annual Reminders.

Because of its abolitionist posture, Pennsylvania became a haven for fugitive slaves from neighboring states. Slave catchers and abolitionists tangled, and some cases were decided by hearings in what came to be known as Independence Hall.

The Grand Federal Procession, a Philadelphia parade celebrating the ratification of the Constitution, began at South and Third Streets on July 4, 1788.

In 1965, discriminatory treatment at a Dewey's restaurant on South Seventeenth Street spurred the first such protest by the LGBT community. Faced with days of protest, the restaurant changed its policy.

Passed while Congress met in Philadelphia, the Alien and Sedition Acts created a political backlash during the presidency of John Adams.

After the work of Independence, the Second Continental Congress worked on drafting the Articles of Confederation, the first Constitution of the United States, at this location.

Vigilance Committees (sometimes called Vigilant Committees) formed to protect fugitives and potential kidnap victims. Robert Purvis was one of Philadelphia's most prominent abolitionists. His home at Ninth and Lombard Streets had a secret area for hiding slaves.

Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) Strike

After the Philadelphia Transportation Company strikes of 1944, the company was bought and taken over by SEPTA, which today has a museum at 1234 Market Street.

The law profession in Philadelphia dates back to the days of William Penn. Over the city's three centuries, it has evolved into a diverse and vital aspect of the city community.

The nineteenth-century phrase 'puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer' means to pose a difficult problem only an expert could solve. Today, Philadelphia lawyers can be seen at work in the Criminal Justice Center on Filbert Street.

Revolutionary Crisis (American Revolution)

On the night of September 16, 1765, a large mob gathered at the State House to target individuals associated with the Stamp Act, including Ben Franklin.

Philadelphians raised money in one week during June 1798 to build the USS Philadelphia to help increase American naval power to protect commerce. The frigate was built at Humphrey’s & Wharton Shipyard on the Delaware River.

Although the federal government under the U.S. Constitution went into operation in New York, the capital moved to Philadelphia in 1790. George Washington lived in the President's House, as did John Adams when he succeeded Washington.

The Meschianza, an elaborate send-off for Gen. William Howe, was held on a plain between the Delaware River and the Walnut Grove estate at what is now Washington Avenue and South Fifth Street.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day observances have been held annually in Philadelphia since the 1970s. A focal point is Girard College, where King held a rally in 1965, as well as a ceremony at the Liberty Bell.

Eastern State Penitentiary, considered by many to be the world’s first full-scale penitentiary, opened in Philadelphia in 1829 and closed in 1971.

In 1851, an attempt to recapture escaped slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania, turned into a riot in which one man was killed. The trial of one of the participants at the Old State House (Independence Hall) reflected growing abolitionist sentiment.

The novel <i>Modern Chivalry</i> was published in installments from 1792 to 1815, wryly documenting life in the new republic. One episode targets pretensions at the American Philosophical Society.

In 1798, a new federal tax and the Alien and Sedition Acts sparked resistance in several counties near Philadelphia. Ringleader John Fries was convicted of treason but pardoned. One clash between federal agents and resisters was at a tavern in Quakertown.

Written by Thomas Paine and published by Robert Bell's print shop at this location on January 10, 1776, the pamphlet Common Sense helped rally support for independence.

While it was the U.S. capital, Philadelphia was site of the first convictions of American citizens of treason—two of ten men tried for participation in the Whiskey Rebellion, which began in 1791 as a protest against an excise tax levied on domestic whiskey. The trial was at Old City Hall in 1795.

Having already captured New York in 1776, British General Sir William Howe devised a campaign to capture Philadelphia in 1777. Howe was able to occupy the city on September 26 of that year. Fort Mifflin, located on Mud Island, was bombarded to open a supply line to the occupied city.

Constitutional Convention of 1787

The Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787, at Independence Hall (then known as the Pennsylvania State House) to draft the United States Constitution.

'Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens'

Musical Fund Hall is where a convention altered the Pa. Constitution to disallow voting by black residents, a move that inspired the essay 'Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Philadelphia,' which argued against ratification.

As the national capital from 1790 to 1800, Philadelphia was the seat of the federal government for a short but crucial time in the new nation’s history.

Forts and other defenses on the Delaware River and, later, along the Atlantic coast guarded Philadelphia and other commercial centers during times of military jeopardy. Fort Mifflin and other surviving forts serve as reminders of the key role forts played in the region's economic, political, and social history.

On October 10, 1871, during a tumultuous and racially polarized Election Day in Philadelphia, Ocatvius V. Catto was shot around here on south street, a block away from his home. Catto spent his life fighting against segregation and discrimination.

By supplying provisions to British military troops or providing safety in the form of row houses on Pine Street for 450 Acadians fleeing Nova Scotia, Philadelphia played a significant role in the Seven Years' War.

Trenton and Princeton Campaign

One of the most significant events in the Revolutionary War was the Continental Army’s crossing of the Delaware River, which preceded three crucial American victories that reignited the virtually extinguished Patriot cause.

The U. S. Congress met in Philadelphia for ten years, testing the endurance of the Constitution and set the groundwork for future political practice.

National Negro Convention Movement

National Negro Conventions held from 1830 to 1864 brought together African Americans to debate and adopt strategies to elevate the status of free Blacks in the North and promote the abolition of slavery.

Although only officially titled in 2005, the Gayborhood has served a vital role in the social and political struggles of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) peoples of Philadelphia since the 1940s.

On October 4, 1779, the house of James Wilson went from being the residence of a wealthy Philadelphia merchant to becoming a stronghold against a rowdy group of militiamen taking action against war profiteers.

Preserved for its eighteenth-century significance as an encampment of the Continental Army during the American Revolution, Valley Forge has a more extensive past and continues to play an integral role in the region’s history and environment.

Dubbed the “Philadelphia Plan,” the program requiring federal contractors to practice nondiscrimination in hiring tested the liberal coalition formed in the aftermath of the New Deal in Philadelphia and nationally.

Philadelphia civil rights leader Leon H. Sullivan first came to Philadelphia to pastor Zion Baptist Church. The Global Sullivan Principles represent one of the twentieth century’s most powerful attempts to effect social justice through economic leverage.

The Knights of Labor, the first national industrial union in the United States, was founded in Philadelphia on December 9, 1869. By mid-1886 nearly one million laborers called themselves Knights.

During the decade the federal capital was in Philadelphia, United States policy toward St. Domingue changed substantially. Important policy decisions emanated from the presidential residence.

An estimated two million visitors attended Bicentennial celebrations, but the summer of ’76 ultimately failed to fulfill the dreams of the city and its planners. Completed projects included a new visitor center for Independence National Historical Park.

Moral doubt over the cruel usage of animals has a long history in Philadelphia.With roots in the late nineteenth century, the PSPCA is among the most active in the nation.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

The American Civil Liberties Union, a national legal organization, organized in Philadelphia in 1951.

Political Parties (Origins, 1790s)

Long considered the “cradle of liberty” in America, Philadelphia was also the “cradle of political parties” that emerged in American politics during the 1790s.

Modeled after the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition in London, the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 exhibited national pride and belief in the importance of education and progress through industrial innovation.

Pennhurst State School and Hospital

During eight decades of continuous operation, Pennhurst evolved from a model facility into the subject of tremendous public scandal and controversy before the federal courts ordered it closed.

Ladies Association of Philadelphia

In 1780, Esther De Berdt Reed penned a broadside titled “Sentiments of an American Woman” to rouse women to participate in the Revolutionary cause.

Early Philadelphia, an Atlantic trading hub, became both a focal point for the slave trade and a community of enslaved Africans. The London Coffee House was sometimes a location for slave trading.

Few regions in the United States can claim an abolitionist heritage as rich as Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was founded in 1775 at the Rising Sun Tavern in Philadelphia.

As a port with longstanding commercial, cultural, and political connections with Spanish America, Philadelphia played a significant role in the era of Spanish-American revolutions and became a center for Hispanic studies.

The French Revolution of 1789 prompted many citizens to flee to the U.S. Most settled along the Delaware River in the Mulberry district of Philadelphia (an area between modern day Market Street, Arch Street, Second Street, and Columbus Boulevard).

Industrial Workers of the World

In the early 1900s thousands in greater Philadelphia belonged to the IWW. Local 8, which organized the city’s longshoremen, was the most powerful and racially inclusive branch in the Mid-Atlantic.

Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition (1913)

The Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Richard R. Wright Sr. founded Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company, as well as the National Freedom Day commemoration, celebrated February 1.

In Philadelphia, the site of the Constitutional Convention, commemoration of the document’s major anniversaries also has been complex and has reflected how regard for the Constitution and its connections to the city have evolved over time.

Representatives of twelve colonies assembled in Philadelphia in September 1774 at Carpenter's Hall in the First Continental Congress.

The Second Continental Congress worked through deep political divisions to create the Declaration of Independence, which was read to the public in Independence Square on July 8, 1776.

Sesquicentennial International Exposition (1926)

In 1926, Philadelphia hosted the Sesquicentennial International Exposition opened to great fanfare but failed to attract enough visitors to cover its costs.

The history of Girard College reflects the history of Philadelphia and the nation. Opened in 1848, Girard College was established under a bequest from wealthy philanthropist Stephen Girard (1750-1831).

Independence National Historical Park

Independence National Historical Park preserves and provides access to Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and other American Revolution and early American history sites.

Originally the Pennsylvania State House, this landmark is associated with the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and is now a treasured shrine, tourist attraction, and World Heritage Site.

For more than a century, the Liberty Bell has captured Americans’ affections and become a stand-in for the nation’s vaunted values: independence, freedom, unalienable rights, and equality.

Mother Bethel AME Church: Congregation and Community

Established in the Revolutionary era, Mother Bethel AME Church is recognized as the genesis of Black religious organizing spirit.

The Philadelphia region provided pioneering models in women’s education, including the Philadelphia High School for Girls, at 1400 W. Olney Avenue since 1958.

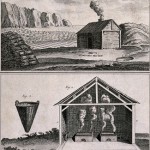

With the Revolution, the young nation lost its main source of salt--England--and needed a new supply. Pennsylvania turned to a scheme involving Toms River, New Jersey, to no avail.

Philadelphia has been at the forefront of women's civil rights activism from its inception to the 21st century. Paulsdale is the preserved childhood home of women's civil rights activist Alice Paul and location of the Alice Paul Institute.

Timeline

Related Reading

Beeman, Richard. Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. New York: Random House, 2009.

Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Mires, Charlene. Independence Hall in American Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

Nash, Gary B. Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720-1840. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Nash, Gary B. The Liberty Bell. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Related Collections

Independence National Historical Park Library and Archives, Merchants Exchange Building, 143 S. Third Street, Philadelphia.

Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, “Quakers and Slavery” online exhibition.

National Archives, The Charters of Freedom online exhibition.

Urban Archives, Temple University, “Civil Rights in a Northern City, Philadelphia” digital archive.

Links

- Video of Greater Philadelphia Roundtable discussion, June 23, 2011

- Time Lapse, The Liberty Bell, by WHYY's Newsworks

- "Cradle of Liberty" Discussion Summary, Greater Philadelphia Roundtable, June 23, 2011

- Researching Slavery and Freedom at the National Archives Mid-Atlantic Region (PDF)

- Charters of Freedom (National Archives)

- Quakers and Slavery (Swarthmore College and Haverford College)