General Trades Union Strike (1835)

Essay

The first general strike in the United States occurred in Philadelphia in 1835 when the short-lived General Trades’ Union (GTU) of the City and County of Philadelphia led a citywide general strike to demand a ten-hour workday. The successful action set a precedent followed by other labor organizations in the nation later in the nineteenth century.

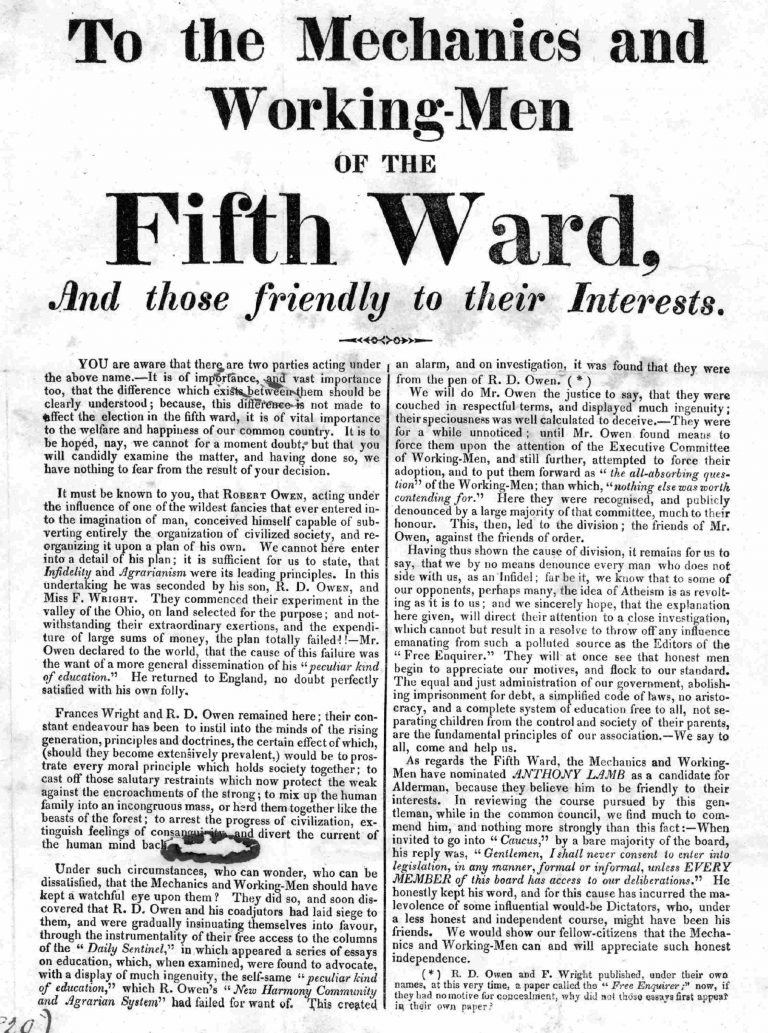

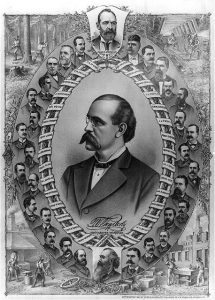

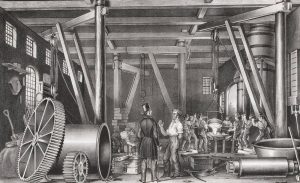

The GTU strike occurred after several failed attempts to organize working people through the creation of a Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations and a Working Men’s Party. In 1833 Philadelphia labor leaders met in hopes of reigniting the city’s nascent labor movement, and they created the GTU the following spring. The GTU, which broke barriers as one of the first labor organizations to accept unskilled workers, became the most remarkable citywide union of its time.

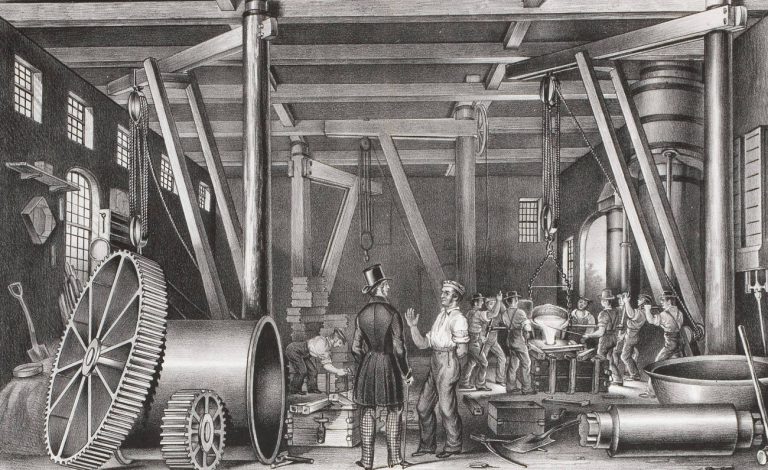

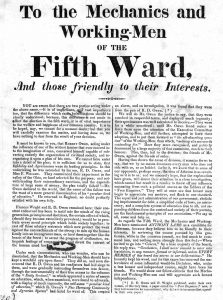

The strike began as an impromptu affair in late May 1835 when coal heavers of the Schuylkill docks went on strike for a ten-hour day. As they paraded down the streets of the city on June 3, cordwainers, carpenters, and other tradesmen followed with the shouts of “We are all day laborers!” Throughout the week leaders of the GTU used labor presses, posters, and parades complete with drum and fife corps demanding a ten-hour day, to rally Philadelphia workers to join their brethren in the fight. By June 10 over forty trades and nearly twenty thousand workers, including city employees, joined the strike. Shortly after city workers struck, the Common Council announced that workers employed under the authority of the City Corporation would be granted a ten-hour day. By the end of June, most laborers received the concessions they asked for, and membership in the GTU soared.

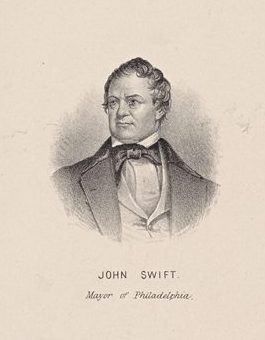

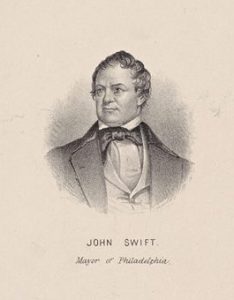

With this initial success, worker solidarity expanded to include unskilled workers, traditionally omitted from unionizing efforts. In the spring of 1836 Schuylkill dockers clashed with coal merchants when they sought a wage advance from their employers. When dockers struck, merchants won the assistance of Mayor John Swift (1790-1873), who had eight day laborers arrested and set their bail at an exceedingly high rate of $2,500 in hopes of breaking the strike. Swift’s plan backfired, however, as the high bail made martyrs of those arrested. The GTU came to their aid, admitted the dockers into the organization, and helped fund their defense, which proved successful when they were acquitted of both breaching the peace and of charges of conspiracy.

GTU power helped to organize the city’s labor and gained the workers of Philadelphia the ten-hour day. Every strike funded and supported by the GTU in the seven months following the general strike ended in victory for the workers, including that of the unskilled dockers. But the organization met a sad end. Many who joined the union left once concessions were made. Workers also faced a backlash from employers who formed masters associations to defeat striking workers. By 1837 only thirty unions remained, down from fifty-one in 1836. That year the first effects of the Panic of 1837 were felt by city workers, and within a year the organization was dead.

While the GTU of Philadelphia proved short-lived, its significance to organized labor movements reached into the next century. The General Strike of 1835, the nation’s first general strike, proved successful and was employed by other American labor movements in the postbellum years, most notably in St. Louis in 1877 and throughout the nation in 1919. By admitting unskilled dockers into their union, the GTU of Philadelphia set a precedent not replicated until after the Civil War when it became a primary objective of the Knights of Labor. Together, the general strike and the inclusion of unskilled laborers in unions ultimately proved effective for organized labor during another dire period for American workers: the Great Depression.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University who is writing his dissertation entitled “The Duty of the State: Policing the State of Pennsylvania from the Coal and Iron Police to the Establishment of the Pennsylvania State Police Force, 1866–1905.” He has been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The formation of the Workingmen's Party of the United States : proceedings of the Union Congress, held at Philadelphia, July 19-22, 1876. (Archive.org)

- Chant of the Coal Heavers: “From Six to Six” (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Labor's Struggle to Organize (ExplorePAHistory.com)