Knights of Labor

By Patrick Grubbs | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

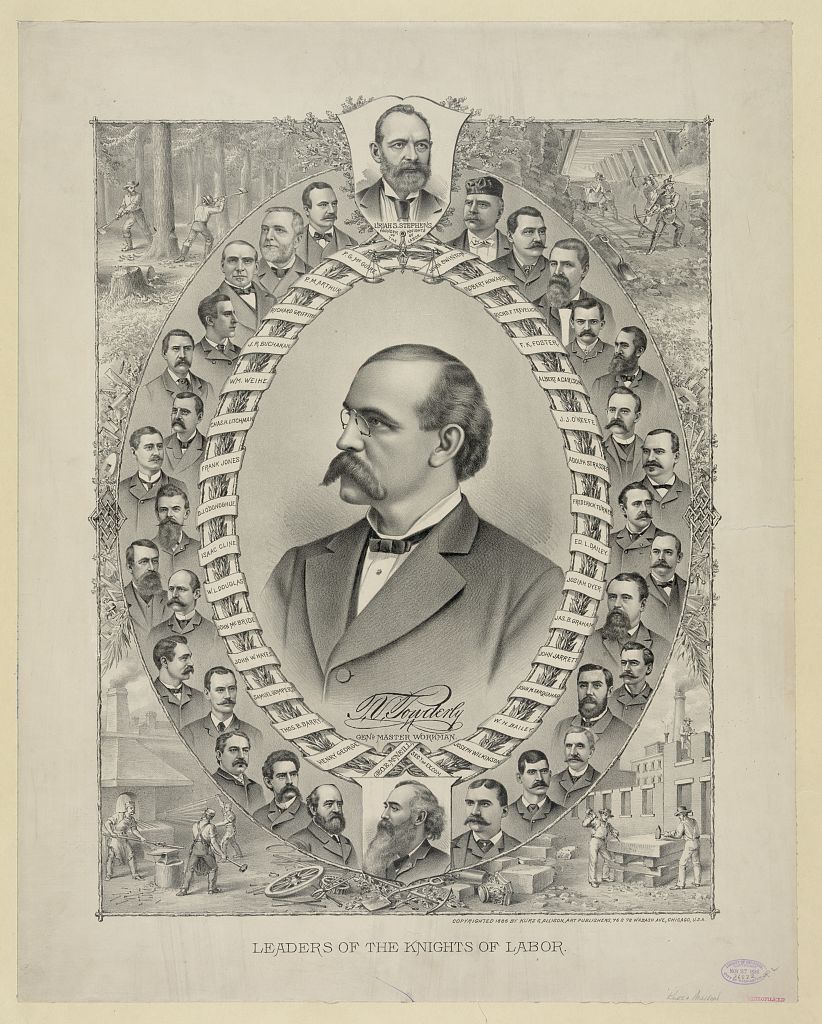

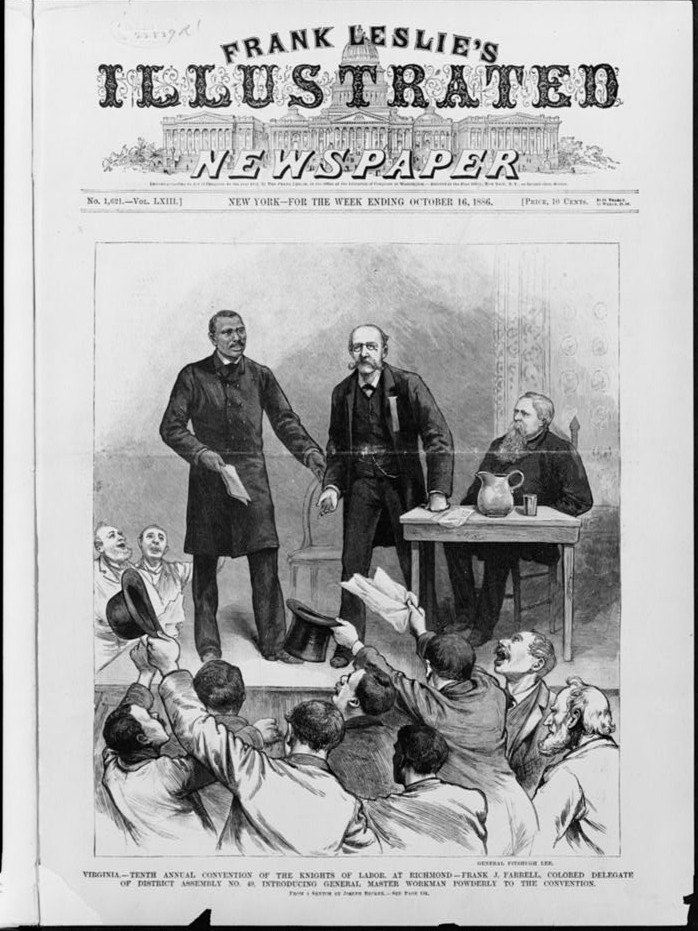

The Knights of Labor, the first national industrial union in the United States, was founded in Philadelphia on December 9, 1869, by Uriah Stephens (1821-82) and eight other Philadelphia garment cutters. Intended to overcome the limitations of craft unions, the organization was designed to include all those who toiled with their hands. By mid-1886 nearly one million laborers called themselves Knights, making the organization the largest and most influential labor union in nineteenth century America.

Originally called the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, the Knights began as a replacement for the failed Garment Cutters Association of Philadelphia. To sustain the organization, Stephens insisted on a high level of secrecy and fraternalism. Not referred to by name until 1879, the organization chalked symbols on sidewalks and buildings to call meetings. For example, the symbol 8 = 415/1 meant Local Assembly (LA) No. 1 would meet on April 15, at 8 o’clock.

Stephens aspired to unite all wage-earners into a single organization regardless of skill, race, or sex. The organization excluded liquor dealers, lawyers, bankers, and professional gamblers. Stephens stressed the importance of solidarity within the ranks of labor in order to meet the power of capital. He did not limit the organization’s goals to increased wages and lower hours, but believed that workers should strive to build co-operatives to gradually replace the prevailing capitalistic system. Because of this outlook the slogan for the organization became “an injury to one is the concern of all.” Despite this lofty goal early membership in the Knights consisted primarily of skilled, male workers. Even LA 1, Stephens’ garment cutters assembly, admitted only garment cutters and no women. Women were not initiated into the Knights until 1882.

Philadelphia Had Most Assemblies

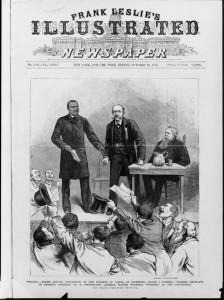

Between December 1869 and April 1875 the Knights made few gains outside of the city. During that time eighty-five local assemblies were established, seventy within the Philadelphia region. After the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 membership expanded and the first national officers were initiated after a convention in Reading, Pa., in 1878. In 1879 Terence V. Powderly (1849-1924), a native of Carbondale, Pa., replaced Stephens as Grand Master Workman after Stephens resigned the position. Powderly, who also served as the socialist mayor of Scranton from 1878-84, led the Knights until 1893.

Powderly eliminated the secrecy of the Knights and membership grew to more than 750,000 by the summer of 1886. From 1879 to 1886 the Philadelphia region maintained a high national percentage of Knight membership and established a meeting house across the street from Independence Hall at 505 Chestnut Street. The Knights in the city also participated in numerous actions on behalf of labor, such as organizing a successful shoemakers strike, striking in sympathy with female carpet makers in 1884, and formulating a local assembly of Italian barbers in 1886.

The Knights declined after 1886, due in part to internal discord in the aftermath of the disastrous violence that erupted during a labor protest in Haymarket Square in Chicago; strong opposition from capital; and competition from the trades unions of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). In 1893 the Knights removed Powderly as its national leader and staggered into the twentieth century after Daniel DeLeon’s failed attempted to make the Knights a Marxist organization. When DeLeon and his followers left the organization in 1895, Knight membership declined and the organization went back into secrecy. Despite its decline, the influence of the Knights continued into the twentieth century. In 1903 labor organizer Mary “Mother” Jones (1837-1930), who was inspired to fight for labor while attending Knights meetings in Chicago in the 1870s, came to Philadelphia to encourage striking textile workers in the Kensington district.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. student of American labor history at Lehigh University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

National History Day Resources

- John M. Davis, "A Defense of the Knights of Labor," 1875 (ExplorePaHistory.com)

- Platform of the Knights of Labor, 1878 (Learn North Carolina)

- Constitution of the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor, 1888 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Thirty Years of Labor, 1859-1889 by Terrence V. Powderly (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)