City of Firsts

Essay

The Convention and Visitors Bureau touts Philadelphia as “a city of firsts.” The Independence Hall Association lists five pages of “Philadelphia Firsts” on its website. A walking tour of the city links “Philadelphia Firsts” to its home page. George Morgan may have been the first to title a book on Philadelphia The City of Firsts, in 1926, but even that far back he acknowledged the research of others who had been tracking those firsts for “many years past.”

The firsts did not begin with Ben Franklin. Philadelphia was a vision before it was a city, and its grandest innovations were in place before Franklin was even born. The ideas that revolutionized the West, religious freedom and political democracy, were proclaimed by William Penn and put into practice by the first sturdy settlers of his colony.

Franklin did do mighty work. But he never did it alone, and the work went on after he left the city and even after he died. Together, in the years before 1800, Philadelphians organized almost all the essential institutions of the modern America that emerged in the nineteenth century. They created the country’s first banks, first insurance companies, and first stock exchange. The first daily newspaper, the first magazine, the first political cartoon, and the first public library. The first patent and the first trade show. The first turnpike and the first steamboat. The first non-sectarian college and the first university, and the first night school. The first hospital, the first medical school, and, maybe more tellingly, the first asylum for the insane. The first law firm and the first formal teaching of the law. The first labor organization and the first strike. The first protest against slavery, the first anti-slavery society, and the first independent African American church. The Army, the Navy, and the Marines, and for that matter the nation itself, and its first flag besides.

The pace of invention scarcely slowed after 1800. In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia claimed America’s first automobile, electric car, advertising agency, collegiate school of business, museums of science and of art, telephone, photograph, professional schools for women, books and magazines for the blind, municipal waterworks, Newman Club, rabbinic college, religious newspaper, YMCA, and more. In the twentieth century, it had the country’s first radio license, television station, modern skyscraper, airmail delivery, scientific management, black-owned-and-operated shopping center, computer, and more.

Fanciful Firsts, Too

And the city birthed not only those great engines of progress but also inventions of delight: the nation’s first circus, balloon flight, merry-go-round, ice cream, soda (and then, inevitably, ice cream soda), pencil with eraser, Girl Scout cookie, western novel, bubble gum, zoo, movie, revolving door, Slinky, uniforms with numbers to identify players, and more.

Still, the census did announce that New York surpassed Philadelphia in population in 1800, and Washington did displace Philadelphia as the national capital at the same time. Later commentators have speculated with numbing regularity that Philadelphians developed an incorrigible inferiority complex after those losses and that the sense of inferiority came naturally to a city of Quakers.

But those speculations are rubbish. Philadelphia was never a city of Quakers – by 1800, Friends were less than a tenth of its population – and Quakers were never so modest. In William Penn’s portrait, he wore a gleaming suit of armor. He turned to Quakerism to temper his pride and try to turn it to love. And the non-Quaker majority was never modest either. Ben Franklin expected that Philadelphia would become the capital of the British Empire and that king and Parliament would in time relocate from the Thames to the Delaware.

When the 1800 census counted more people in New York than in Philadelphia, arrogant Philadelphians simply refused to credit the count. Even in 1810, when the next tally found New York’s advantage increasing, Philadelphians still maintained that their city was larger. By 1820, they did finally concede that New York might have more inhabitants, but they insisted that Philadelphia excelled its upstart rival in law, medicine, science, art, architecture, and every other amenity of cosmopolitan culture.

Discouraging Pattern

Philadelphians did eventually grow discouraged competing with the emerging colossus to the north. After decades, even generations, of primacy, they did ultimately reconcile themselves to second place in the American urban pecking order. And when they did – when they gave up measuring themselves against New York – they launched on their most distinctive and most marvelous innovation of all.

Others cities followed New York, and in boosting and boasting they still do. Long before the nineteenth century was out, Philadelphia ceased to be an American city in that sense. It gave up braggadocio as a way of life.

It did, to be sure, mount the Centennial of 1876. It did send the Liberty Bell on promotional tours of the nation for decades. But it did so in its own chastened way. As observers as different as Henry James and Lincoln Steffens said, it became a city peculiarly contented with itself. It did not imbibe modesty from its Quaker founders, but it did not imbibe the American disease of belief in divine blessing from them either. Quaker egalitarianism precluded such a sense of chosenness. Quakers considered themselves merely a people among peoples. They lived well, but they did not trumpet that they lived better than anyone else.

In the nineteenth century, in New York, the Four Hundred made fabulous fortunes while the Four Million scrambled to escape the city’s tenements and slums. In Philadelphia, the American Dream that Franklin first formulated actually touched the masses. As one observer put it, in 1877, the city “exceeded in comfort within the reach of the poorest classes any other city in the world.” At a time when barely a fifth of New Yorkers did, most Philadelphia families owned their own homes. The city’s people were skilled workers who made good wages, not de-skilled employees whose labor made their bosses rich. In significant numbers, they even had vacation homes in the mountains or down the shore, a full generation or two before unions and the New Deal brought such benefits to workers elsewhere.

When Philadelphia ceased to be the first city, it took to itself the title of city of firsts. The title was at once a harmless expression of pride and a profound expression of identity. It signified a place that could look backward and appreciate its past as New York never did. A city civilized in an un-American way. A city urbane as well as urban. A city of well-being as well as wealth. A city that could be an object of affection as well as an arena of ambition. Perhaps, as Penn hoped, a city of love. Certainly, a city to love.

Michael Zuckerman is Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

This essay is published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.

Related Topics: Innovations and "Firsts"

Themes

Essays

- Basketball (Professional)

- Aeronautics and Aerospace Industry

- Dinosaurs and Paleontology (Study of Fossils and Prehistoric Life)

- Fire Escapes

- Gospel Music (African American)

- Community Colleges

- Street Numbering

- Paper and Papermaking

- Pharmaceutical Industry

- Soccer

- Textile Manufacturing and Textile Workers

- Mennonites

- Dispensaries

- PSFS

- Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

- Armories

- Toy Manufacturing

- Botany

- Magdalen Society

- Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

- Bartram’s Garden

- Clocks and Clockmakers

- Classical Music

- Telephones

- Nursing

- Literary Societies

- ENIAC

- Roman Catholic Parishes

- Furnituremaking

- Single Tax Movement

- General Trades Union Strike (1835)

- Historical Societies

- Pennsylvania Prison Society

- Cricket

- Locomotive Manufacturing

- Cordwainers Trial of 1806

- Helicopters

- Hail, Columbia

- Chemistry

- Artisans

- Chemical Industry

- Root Beer

- Meteorology (Study of the Atmosphere)

- Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

- Peale Family of Painters

- Art of Dox Thrash

- Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania

- Military Bases

- Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

- Scientific Societies

- American Philosophical Society

- Home Remedies

- Staircase Group (The)

- Coal

- Women’s Education

- University City Science Center

- Astronomy

- Pennsylvania (Founding)

- Radio (Commercial)

- Fairmount Water Works

- Philadelphia Orchestra

- Entomology (Study of Insects)

- Bank of the United States (First)

- Slinky

- College of Physicians of Philadelphia

- Sports Cards

- Herpetology (Study of Amphibians and Reptiles)

- Vegetarianism and Veganism

- Model Cities

- Cartoons and Cartoonists

- Dentistry and Dentists

- Dewey’s Lunch Counter Sit-In

- Prehistoric Native Peoples and Archaeology

- Bank War

- Thanksgiving

- Monopoly

- U.S. Presidency (1790-1800)

- Godey’s Lady’s Book

- Gothic Literature

- Printmaking

- U.S. Mint (Philadelphia)

- Eastern State Penitentiary

- Tun Tavern

- Plantations

- Lewis and Clark Expedition

- Junto

- Constitutional Convention of 1787

- Philadelphia Social History Project

- Cast Iron Architecture

- Scientific Management

- Gallery at Market East

- Television

- Hoagies

- Medical Publishing

- Arboretums

- Insurance

- Recording Industry

- Knights of Labor

-

Roman Catholic Education

(Elementary and Secondary) - Fox Hunting

- Centennial Exhibition (1876)

- Banking

- Department Stores

- Mother Bethel AME Church: Congregation and Community

- Cycling (Sport)

- Settlement Houses

- National Constitution Center

- Lutherans and the Lutheran Church

- African American Museum in Philadelphia

- Methodism and Methodist Churches

Map

Professional basketball has a long history in the Philadelphia region, from the first professional league, formed in 1898, to the NBA. During the 1940s, the Warriors drew crowds to the Philadelphia Arena at Forty-Fifth and Market Streets.

The Philadelphia area has played a major part in paleontology, yielding discoveries that have helped to illuminate millions of years of existence. Fossils found at the former Inversand Quarry in Sewell, N.J., date to the Cretaceous Period.

Philadelphia enacted the first municipal law mandating fire escapes on all sorts of buildings and is associated with a design innovation: Philadelphia fire tower, as seen near Thirteenth and Walnut Streets.

Two-year, public colleges—commonly known as community colleges—became a fixture in the Philadelphia area in the second half of the twentieth century. The Community College of Philadelphia opened in 1965.

Philadelphia played a key role in the birth of the American pharmaceutical industry during the early nineteenth century. The Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (now USciences) was the nation's first pharmacy college.

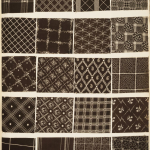

Textile Manufacturing and Textile Workers

Textile production bolstered Philadelphia's economy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Factories like Manayunk's Washington Print Works, which produced the patterns at right, shipped goods nationwide.

German Mennonites were among the first settlers in Philadelphia in the early 1680s. The 1770 Germantown Meetinghouse remains open as a museum and historic site.

Free clinics known as dispensaries served the “working poor” from the eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries. The Philadelphia Dispensary for the Medical Relief of the Poor, considered the nation’s first, opened in 1786 and erected a new building on Fifth Street in 1801.

Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

Philadelphia's connections to the Pacific World are as old as the city itself, including early participation in the China Trade and the first Japanese gardens in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition.

Philadelphia helped define the toy industry in the United States with simple yet engaging toys that became beloved by generations. Schoenhut's Humpty Dumpty Circus featured a camel, which is now housed at the Philadelphia History Museum at Atwater Kent.

Founded in 1800 and located at Twenty-First and Race Streets, the Magdalen Society of Philadelphia was the first institution in the United States concerned with caring for and reforming “fallen women.”

Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

Founded in 1882 to address social issues in Philadelphia, the Children's Aid Society of Pennsylvania merged in 2008 with the Philadelphia Society for Services to Children and formed Turning Points for Children.

Established in 1729 by John Bartram, Bartram's Garden is the oldest botanical garden in the United States.

Clockmakers beginning in the colonial era have made clocks that have become Philadelphia landmarks, including the Thomas Stretch clock at Independence Hall.

Philadelphia has been home to prestigious classical music groups, venues, and schools like the Settlement Music School. Composers in Philadelphia also wrote the first classical pieces penned in the American colonies.

The telephone was first demonstrated at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Since then Philadelphia has been home to many telephone innovations and several telephone companies, including Bell Telephone, which built offices at 1827 Arch Street.

Literary Societies provided Philadelphia's elite with a place for intellectual and artistic discourse. Some, like the Acorn and Rittenhouse Clubs, remained active in the twenty-first century.

Philadelphia has been home to Catholic parishes since the colonial era. Despite declines in recent decades, the church maintains a strong presence. Old St. Joseph's on Willings Alley opened in 1733.

An abundance of local and imported woods, a large immigrant population, and a bustling port combined to make Philadelphia one of the centers of American furniture making in the Colonial and Early Republic eras. Many examples are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Philadelphia helped give birth to the single tax movement, popularized by economist and Philadelphia native Henry George, whose birthplace is on South Tenth Street.

General Trades Union Strike (1835)

The General Trades Union Strike of 1835 was the nation's first general strike, prompted by coal heavers working along the Schuylkill River and demanding a ten-hour day.

Since the early nineteenth century, a number of historical societies have called Philadelphia home, from small religious and local history groups to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Spurred by reports of deplorable conditions at the Walnut Street Jail, a nondenominational group of religiously motivated activists set out to reform Philadelphia's prisons. Their reforms soon spread to prisons around the world.

Baldwin Locomotive dominated the steam-locomotive business. In 1906 alone, the Baldwin Locomotive Works produced 2,666 steam locomotives and employed more than eighteen thousand workers at its facilities on North Broad Street.

Philadelphia was the cradle of the nation's rotary-wing aviation in the twentieth century. The Piasecki Aircraft Corporation, formed in 1955 and located in Essington, produced the world’s first shaft-driven compound helicopter in 1962.

Joseph Hopkinson lived on Spruce Street while he was drafting the lyrics to 'Hail, Columbia,' which for many years served as the unofficial national anthem.

Greater Philadelphia was a chemical center from the eighteenth century. In 1864, Harrison Brothers opened a massive facility on Gray's Ferry Avenue. In 1917, DuPont purchased the entire Harrison Brothers enterprise.

Meteorology (Study of the Atmosphere)

Philadelphians have pursued significant scholarly and popular interests in meteorology since the eighteenth century. The National Weather Service provides local forecasts from its base in Mount Holly, N.J.

Since the early nineteenth century, the Academy of Natural Sciences has sought to fulfill a dual mission of scientific discovery and the diffusion of knowledge.

For over 125 years, the family headed by Charles Willson Peale formed a prolific artistic dynasty. Their homes included Belfield farm, purchased by Peale in 1810 and later part of La Salle University.

Dox Thrash developed his skills as a printmaker under at the Graphic Sketch Club, which in 1944 became the Samuel S. Fleischer Art Memorial.

Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania

The first medical school in the world for women authorized to award them the M.D., Woman's Medical College moved to this location In 1862.

Since the American Revolution era, military bases have shifted in size and economic impact during times of war and peace. The Naval Shipyard in South Philadelphia, where 22,000 workers once built ships, became The Navy Yard office park.

Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

Military veterans began organizing during the waning days of the Revolutionary War and continued to form organizations such as the Philadelphia Veterans Advisory Commission, established in 1957 and located in City Hall.

Since the colonial era, Philadelphia scientists have formed scientific societies. Many, including the Wagner Free Institute of Science in North Philadelphia, still exist and operate museums.

American Philosophical Society

Established in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin and John Bartram to 'promote useful knowledge,' the American Philosophical Society brought renown to colonial scientists. It continues its intellectual pursuits on Fifth Street near Walnut.

From the earliest days of Philadelphia, local residents have used plants, tonics, and Native American wisdom to avoid a visit to the doctor's office. 'Curative' soda has roots at the Physick House on Fourth Street

Originally displayed in Philosophical Hall on Independence Square, this trompe l'oeil double portrait by Charles Willson Peale gained new attention after its display in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the twentieth century.

The Philadelphia region provided pioneering models in women’s education, including the Philadelphia High School for Girls, at 1400 W. Olney Avenue since 1958.

University City Science Center

University City Science Center, the nation's first urban research park was conceived as an ambitious urban renewal project, but ignited racial tensions in a city marred by poverty. After a slow start, the Science Center eventually prospered.

In 1681 the king of England granted William Penn a charter to found Pennsylvania, but the colony did not evolve exactly as Penn had foreseen it. Among the First Purchasers were Germans who called their section Germantown.

Philadelphia had many roles in the growth of commercial radio, including the manufacture of radios. For a few years, Atwater Kent, with a plant on Wissahickon Avenue, was the country's top radio maker.

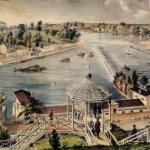

Built in the early nineteenth century to supply the growing city of Philadelphia with water, the Fairmount Waterworks property became cornerstone of one of the biggest city-run parks in North America.

Founded in 1900, the Philadelphia Orchestra developed into an iconic organization for Philadelphia and cultural ambassador to the world. The orchestra's home is the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts.

Naturalists and illustrators helped make Philadelphia a center for the study of insects—entomology—as early as the eighteenth century. The butterfly collection of Titian Peale today resides in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

Bank of the United States (First)

Originally located in Carpenters' Hall, the First Bank of the United States relocated to 116 S. Third Street in 1797.

College of Physicians of Philadelphia

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia was founded in 1787 “to advance the science of medicine and to thereby lessen human misery.” It created professional standards and provided for the exchange of medical knowledge, while also establishing a renowned medical library and medical museum.

Sports card collecting has strong ties to Philadelphia, where three companies--American Caramel, Fleer Corporation, and Bowman Gum--were pioneers. Fleer's final plant before it closed was on Tenth Street in the Olney section.

Herpetology (Study of Amphibians and Reptiles)

Amphibians and reptiles fostered rich scientific discussions among early Philadelphia naturalists, including William Bartram and Charles Willson Peale, and the Academy of Natural Sciences published research on the subject.

U.S. vegetarianism got its start in Philadelphia—Ben Franklin practiced it for a time. In the twenty-first century, the restaurant Vedge on Locust Street brought cutting edge vegan fare to Philadelphia.

The Model Cities program called for federal services to redevelop the nation’s poorest communities. In 1967, North Philadelphia was designated for renewal, but efforts faltered and goals changed, with a textile company moved from North Broad Street to Spring Garden and Seventh Street.

As political, economic, and cultural capital of the early U.S., Philadelphia became a center for producing political cartoons and humorous caricatures, starting with Benjamin Franklin's widely reprinted 'Join, or Die' cartoon.

Innovative dentists in Philadelphia helped to shape dental care, procedures, and tools. The S.S. White firm, with a factory located here in the 1880s, became a premier manufacturer of dental tools.

In 1965, discriminatory treatment at a Dewey's restaurant on South Seventeenth Street spurred the first such protest by the LGBT community. Faced with days of protest, the restaurant changed its policy.

Prehistoric Native Americans and Archaeology

Since the late nineteenth century, archaeologists have been digging for remnants of Native American life in the Philadelphia area, including a rural site in Pilesgrove Township, Salem County, N.J.

Thanksgiving Day traditions evolved over time while retaining themes of early thanks-giving feasts. Philadelphia, home to the first Thanksgiving Day Parade, contributed to many traditions as they came to be practiced across the nation. In Philadelphia, the parade goes up Franklin Parkway to the Art Museum.

Although the federal government under the U.S. Constitution went into operation in New York, the capital moved to Philadelphia in 1790. George Washington lived in the President's House, as did John Adams when he succeeded Washington.

Godey’s Lady’s Book was the first successful women’s magazine and most widely circulated magazine in the antebellum United States, published on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia is the birthplace of gothic literature in America. One of its early purveyors was Edgar Allan Poe, who lived in Philadelphia for six years. His home at 530 N. Seventh Street is a national historical site.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia became a leading center of printmaking in the U.S., a legacy that lives on at sites such as the Brandywine Workshop on Broad Street.

United States Mint (Philadelphia)

Coins have been minted in Philadelphia as long as the federal government has produced legal tender coins. Since 1969, the mint has been located on the edge of Independence Mall, its fourth location in the city.

Eastern State Penitentiary, considered by many to be the world’s first full-scale penitentiary, opened in Philadelphia in 1829 and closed in 1971.

For nearly a hundred years from 1693 to 1781, Tun Tavern served residents and visitors of Philadelphia near the Delaware River waterfront with food, spirits, and sociability.

Small farms and larger properties called plantations drove the Mid-Atlantic's colonial economy. The Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation is a living history site focusing on 1760-90 farm life in southeast Pennsylvania.

The American Philosophical Society, located here in Philosophical Hall, received specimens from Lewis and Clark's expedition to the West.

Constitutional Convention of 1787

The Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787, at Independence Hall (then known as the Pennsylvania State House) to draft the United States Constitution.

Philadelphia Social History Project

The Philadelphia Social History Project (PSHP) was an interdisciplinary project that played a central role in transforming the study of urban and social history by creating a computerized database to study the effect of industrialization and urbanization on Philadelphia’s minority populations between 1838 and 1880.

From 1840 through 1880, a commercial district of cast iron buildings developed in Center City, helping to define the downtown of the emerging modern city, clustered from the Delaware waterfront to Twelfth Street between Arch and Pine Streets. The Smythe Stores building is now a residential building.

The system of scientific management pushed companies to find the most efficient way to complete tasks. Frederick W. Taylor began to practice efficiency methods at Midvale Steel, located here, in the 1870s.

The Gallery at Market East attempted to revitalize Philadelphia’s deteriorating retail space by luring suburban shoppers to Market Street. The Gallery offered shoppers easy access to the city's public transportation and an indoor shopping space.

Philadelphia's role in the development of television began in the 1930s when solitary inventors and corporations began investigating the possibility of transmitting moving images over the air to a home receiver. Today, the Comcast building is the tallest in the city.

Washington Square in the early twentieth-century served as the nexus for three of Philadelphia's most prominent medical publishers. Medical students throughout the country read textbooks and manuals produced by these medical publishers.

The Philadelphia area is a recognized “hearth” of early American arboretums. Starting almost exclusively within a tight-knit community of Quaker botanists, early Philadelphia arboretums left a legacy of emphasis on native plants.

In Camden, New Jersey, the Victor Company in the early 1900s was nation’s largest manufacturer of musical recordings.

The Knights of Labor, the first national industrial union in the United States, was founded in Philadelphia on December 9, 1869. By mid-1886 nearly one million laborers called themselves Knights.

Roman Catholic Education (Elementary and Secondary)

For more than three centuries Parochial schools in the Philadelphia region have responded to the changing characteristics of the region’s Catholic population.

Fox hunting became a popular leisure activity in the Philadelphia region during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In October 1766, twenty-seven Philadelphia professionals founded the Gloucester Fox Hunting Club, the first of its type in America.

Modeled after the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition in London, the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 exhibited national pride and belief in the importance of education and progress through industrial innovation.

Led by John Wanamaker, Philadelphia's Market Street department stores became the national model. Known as the "Big Six," these businesses were close to the city's rail terminals and subway stations.

Mother Bethel AME Church: Congregation and Community

Established in the Revolutionary era, Mother Bethel AME Church is recognized as the genesis of Black religious organizing spirit.

The Philadelphia International Cycling Classic made famous the “Manayunk wall,” where thousands of spectators lined Lyceum Avenue to watch cyclists ascend the 285-foot climb with a 17 percent grade at its steepest segment.

The settlement house movement spread to Philadelphia in the 1890s as a large influx of needy immigrants and unsanitary conditions in the city attracted the attention of middle-class, college-educated reformers.

African American Museum in Philadelphia

The African American Museum in Philadelphia (AAMP) was the first major museum of Black history and culture established by an American city.

Timeline

Related Reading

Morgan, George. City of Firsts: Being a Complete History of the City from its Founding, in 1682, to the Present Time. Philadelphia: Historical Publication Society, 1926.

Zuckerman, Michael. “The Making and Unmaking of the Pennsylvanian Empire.” In Randall Miller and William Pencak, eds., Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2002.

Related Collections

George Morgan Papers, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, 181 S. College Avenue, Newark, Del.