Banking

By Michael A. Martorelli | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Greater Philadelphia’s banking roots go deeper than those of any region in the country. Philadelphia was the home of the first commercial bank (1782), the first national bank (1791), the first savings bank (1816), and the first savings and loan association (1831). Until the mid-1980s, celebrated local institutions such as First Pennsylvania, Girard, and Provident dominated the region. By the late twentieth century, however, historic regulatory changes led to acquisitions by out-of-town giants and changed the face of the banking industry both locally and nationally.

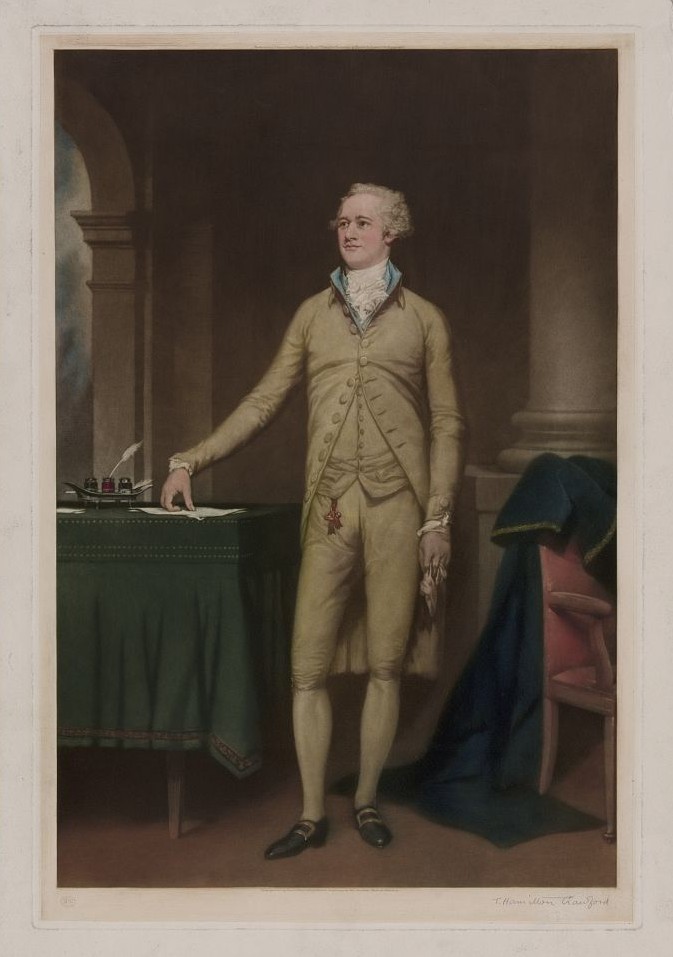

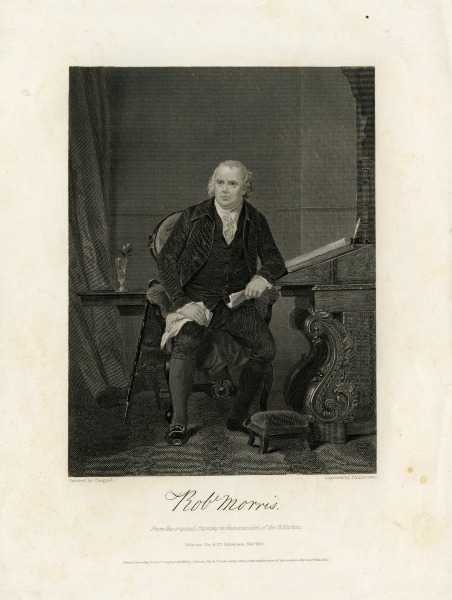

The region’s prominence in banking began with the creation of the Bank of North America in 1781, when Philadelphia was the largest and most important city in North America. In February 1781, even as the War for Independence still raged, the Continental Congress appointed as its Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris, a partner in a successful mercantile house and one of the city’s best-known businessmen. Shortly after, and building on both his ideas and those of the precocious Alexander Hamilton, Morris received congressional approval to establish the first commercial bank in the country. At first it was difficult to attract capital, but by early 1782, the Bank of North America was ready to open for business. The BNA loaned money to the federal and state governments as well as to many of the city’s businesses, thereby facilitating commerce among the colonies and between the United States and other countries.

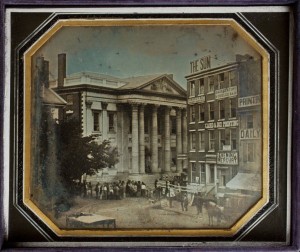

Soon after ratification of the Constitution of the United States in summer 1788, commercial banks sprouted in more than a dozen other cities. The Bank of Pennsylvania (1793) was the second founded in Philadelphia, and the Delaware legislature chartered the Wilmington-based Bank of Delaware in 1795. Meanwhile, in 1791, Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton followed through on one of his long-standing ideas – a national bank whose main purposes would be to collect taxes, hold government funds, and make loans to the government and other worthy borrowers. While it would be a private institution with a twenty-year charter from Congress, the Bank of the United States would be more national than local in scope. Four years after its founding, it moved to Third and Chestnut Streets, where a new Greek revival building with a Roman portico and Corinthian columns suggested solidity and stability.

The first decade of the nineteenth century saw the establishment of several more banks in Philadelphia. Adding to the earlier institutions that largely served the needs of governments, upper class merchants, lawyers, and influential businessmen, the Philadelphia Bank (1803), Farmers and Mechanics Bank (1809), Commercial Bank (1810), and Mechanics Bank (1810) were formed by and for artisans, farmers, mechanics, and manufacturers. In 1810, the leaders of the District of Northern Liberties, just north of Vine Street but not served by the Philadelphia banks, formed the Bank of Northern Liberties. Another innovation occurred in 1816 when a group of businessmen, inspired by the success of savings institutions in England and Scotland, established the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society to cater to small depositors not targeted by commercial banks. The depositors owned this “mutual” savings bank, and shared in its profits. Long after the bank’s demise, the iconic PSFS sign atop the re-purposed skyscraper at 1200 Market Street continued to light the Center City sky.

Local Banks Arise

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, citizens in Delaware and New Jersey also established banks for their own use. In 1807, Delaware authorized the Farmers Bank of the State of Delaware and established its headquarters in Georgetown, enabling it to serve the farming communities in the state’s southern townships. During the following ten years, the state authorized three more banks in Wilmington. New Jersey established its first banks in Newark and Trenton in 1804. In 1812, it chartered six more banks, including the State Bank at Camden, the first in the southern portion of the state.

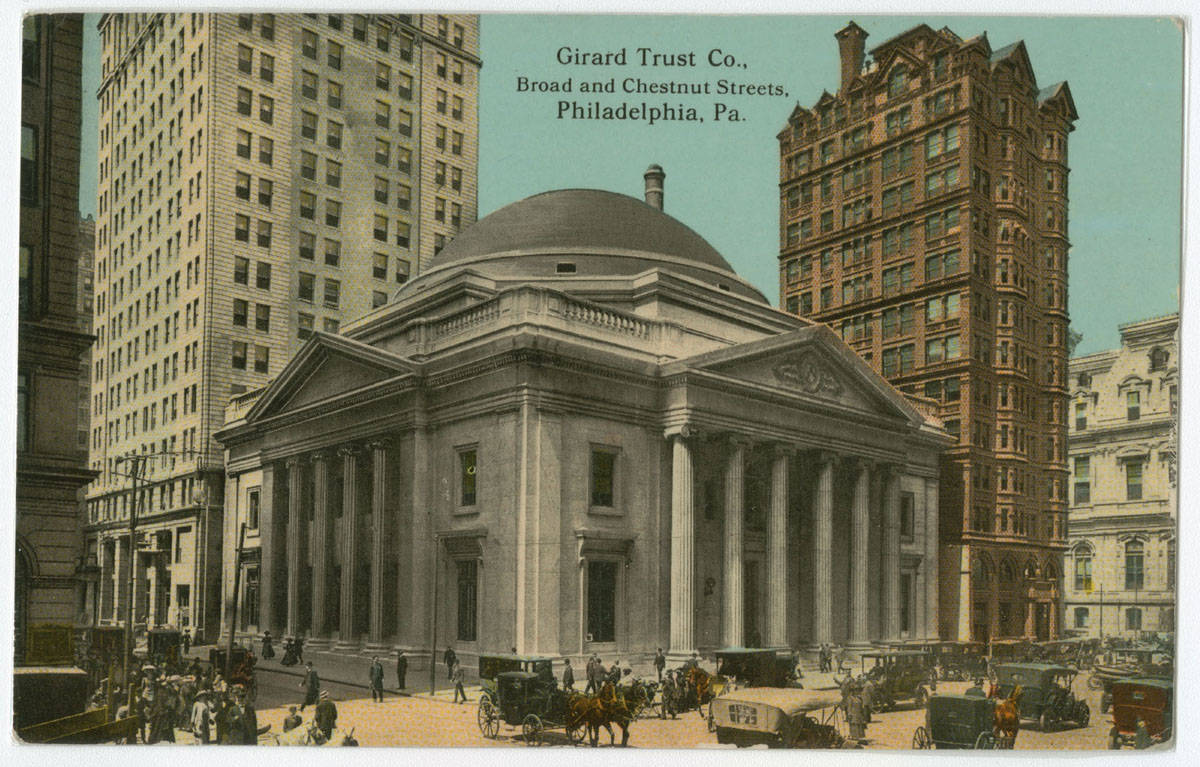

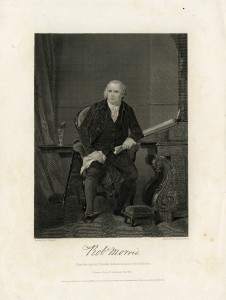

Although Philadelphia was no longer the nation’s capital after 1800, the presence of the Bank of the United States kept the city at the center of controversies about the nation’s finances. In 1811, anti-banking forces in Congress refused to extend its charter. Republicans believed the bank was unconstitutional, and that it benefitted only the moneyed class at the expense of all others. Local merchant and trader Stephen Girard acquired its building and fixed assets, and used his own capital to establish the Bank of Stephen Girard as the country’s first private bank, a bank with no publicly traded shares and no mandated service to customers.

Philadelphia became home to a national bank once again in 1816, following the wreckage to the economy caused by the War of 1812 (1812-15) with Great Britain. Congress realized the need for another national bank to help regulate the supply of credit and expedite the financial dealings of the federal government. Philadelphia was still a leading financial center, so it was no surprise when Congress decided to headquarter the Second National Bank of the United States among the other banks on Chestnut Street. The bank operated out of Carpenters’ Hall for five years, and then opened in 1824 in its new Greek Revival structure modeled on the Parthenon, a symbol of strength and permanence.

Banking in Pennsylvania expanded after the Commonwealth’s Omnibus Banking Act of 1814 divided the state into twenty-seven banking districts and approved charters for forty-one banks. Banking was a profitable business; businessmen across the Commonwealth urged the legislature to authorize the formation of more institutions. Citizens quickly organized banks in Bristol, Chester, Germantown, Norristown, and West Chester. The law imposed several new financial requirements on the institutions. One robbed the banks’ managers of the ability to make loans in any amount, to any worthy borrower, in any location. That restriction failed to recognize the law of supply and demand for credit. Many new banks freely supplied more credit than was demanded by worthy borrowers, and maintaining that excess supply of money was not sustainable. Within a few years, more than 40 percent of the new banks in Pennsylvania failed.

Stronger Banks’ Role in Commerce

Philadelphia’s long-established banks survived, and they became important cogs in the state’s attempts to battle New York and Baltimore for commercial supremacy during the next two decades. As early as the 1760s, some of the city’s political leaders understood the need to augment Philadelphia’s strong position in overseas commerce with expanded business ties with inland areas to the north and west. In particular, they believed the city needed to build stronger transportation connections with central Pennsylvania and its fertile Susquehanna Valley. State officials finally embarked on a crash program to create those much-needed commercial corridors. Throughout the 1830s, banks seeking the mandated renewals of their charters were compelled by law to loan the state the funds to execute that program.

Although the state got its canals and turnpikes, most were unprofitable because they could not prevent lucrative commercial traffic from using other transportation corridors to the ports of New York and Baltimore. Pennsylvania’s revenue decreased even as its debt level ballooned. Bank creditors forced to finance those construction projects throughout the 1820s and 1830s suffered financially when the state suspended interest payments on its debt in 1841 and then demanded that the banks extend even more loans.

In Philadelphia, meanwhile, the Second Bank of the United States became the flashpoint for the national political conflict known as the “Bank War.” Soon after his election as President in 1828, Andrew Jackson made clear his displeasure with banks in general and the Second Bank of the United States in particular. In his view a large central bank, controlled and operated by the moneyed class, limited the growth of the hundreds of state banks that had sprouted in the previous quarter century. During the closing months of 1831, and in anticipation of the election of 1832, President Jackson tempered his arguments against the Bank. However, Bank President Nicholas Biddle was emboldened by the December 1831 recommendation for re-chartering the Bank by the Secretary of the Treasury. Spurred on by leading Philadelphia businessmen Biddle unwisely sought to forcefully blunt Jackson’s campaign against his institution by applying for a new charter in 1832, some four years before its first charter expired. Congress passed this re-charter bill, but was unable to override Jackson’s veto. The re-elected President then emasculated the bank by first transferring government funds to other banks, then convincing his allies in Congress to refuse another re-chartering effort. As the bank wound down its affairs, the contraction of loans, discounts, exchanges, and deposits led to severe economic dislocations before the bank closed its doors in 1836. Following that closing, and searching for still more funds to finance internal improvements, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania immediately granted a state charter to a successor bank that promised both to loan the state additional sums and to pay a bonus for the privilege of operating. Working under such onerous restrictions, the new United States Bank of Pennsylvania failed only five years later – and took six other Philadelphia banks with it.

Banks Multiply Despite Panics

Philadelphia’s banks suffered proportionately in the financial panics that gripped the nation in 1837 and 1857. Yet, throughout the period, entrepreneurs continued to establish new banks. Most of the action occurred in outlying districts of the city such as Kensington, Moyamensing, Southwark, and Spring Garden. Before and after the Civil War, political lending became less important as most of the city’s institutions sought to finance a growing number of railroads and manufacturers. After the Panic of 1873, many mergers among the surviving banks enabled those institutions to serve the needs of local and national firms during the manufacturing boom of the industrial revolution. A handful of these acquisitive institutions evolved into such stalwarts of the twentieth century as Fidelity, Girard, and Provident, joining the successors of the Philadelphia Bank (Philadelphia National) and the Bank of North America (the Pennsylvania Company, later First Pennsylvania) as market leaders. After the turn of the twentieth century, many of the region’s banks further expanded their business with a nationwide clientele. Their appetite for acquisitions remained strong; as a result of merger activity, the number of banks in Philadelphia declined from 1900 to 1914.

During the years immediately after World War I, the banking franchise broadened to involve more businesses and citizens than ever. Corporations (such as Gimbel Brothers), unions (such as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers), and the community leaders of various minority, ethnic, and religious groups established commercial banks, mutual savings banks, and trust companies throughout the region. The largest commercial banks continued their merger and acquisition sprees, and they supplied the capital that funded the growth of utility and industrial companies.

The Great Depression devastated the banking community, particularly in the working-class neighborhoods. One-third of Philadelphia’s banks failed, including such high-profile institutions as Bankers Trust, with more than 100,000 depositors. Institutions in North and South Philadelphia, areas with high percentages of immigrant and working-class customers, collectively lost as much as 45 percent of their deposits. The losses were closer to 15 percent for banks doing business in the Northwest sections of the city or the central business district. One prominent survivor was the Citizens and Southern Bank at Nineteenth and South Streets, founded in 1921 by the civil rights advocate and entrepreneur Richard R. (“Major”) Wright Sr. as the only African American-owned bank in the North. Indeed, his conservative lending policies helped the bank become one of the first in the nation to open after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1933 bank holiday. (His successors sold the bank in 1957.) Market leaders such as Fidelity, Girard, and Provident also survived the Depression but made few acquisitions throughout the period. The result was the emergence of a smaller but more stable banking community by the 1940s.

Philadelphia’s banks prospered along with the city in the first two decades after the end of World War II. Competition among the institutions that served Philadelphia and its contiguous counties was constrained; branch banking had long been severely limited, and interstate banking was prohibited. But in the 1970s, firms such as American Express, General Motors, Merrill Lynch, and Sears Roebuck began offering loan and deposit services that made such longstanding banking restrictions less relevant. Regulations governing the banking business were seriously eroded by new technologies and new entrants to the marketplace. Competition became even more intense during the early 1980s, when Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware joined other states in allowing statewide branching and then intra-state mergers. In 1994, Congress passed the Riegle Neal Act, removing all restrictions on inter-state banking. Finally, in 1999 President William Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act; it removed all remaining barriers between commercial banks, savings banks, investment banks, and other types of lending and depository institutions, thus remaking the landscape of the financial services industry.

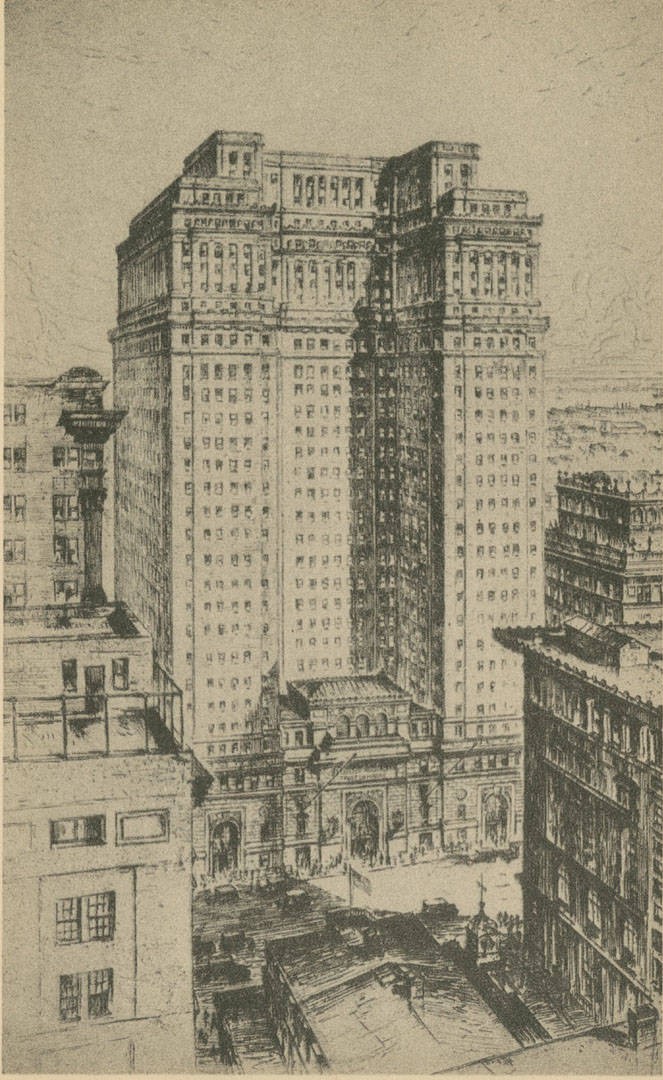

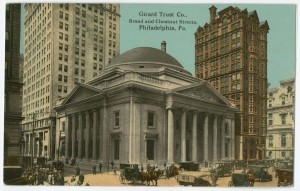

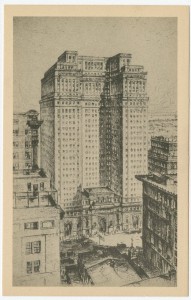

From 1983 to 1998, seven of the eight largest locally based institutions succumbed to acquisitive initiatives by larger so-called “super-regional” organizations. Those transactions robbed Philadelphia of its place as a headquarters city for prominent commercial banks. Philadelphia National Bank (PNB) emerged as the only locally based super-regional. It adopted the name CoreStates Financial and acquired banks in Lancaster, Reading, Trenton, and Philadelphia. Only the PNB sign atop the building at Broad and Chestnut Streets remained to hint of that institution’s legacy. (In 1998, Charlotte’s First Union Corporation acquired CoreStates, but a decade later First Union became part of Wells Fargo, headquartered in San Francisco.)

Among the dozens of institutions providing banking services to consumers and businesses in Greater Philadelphia, by 2010 only WSFS Bank in Wilmington could trace its founding as far back as 1832, when it was established as the Wilmington Savings Fund Society. Philadelphia’s Beneficial Bank, formed as a mutual savings bank, was established in 1853; and two other institutions headquartered in Philadelphia’s suburbs had legacies dating to the 1870s (Univest and National Penn Bancshares). Some newer organizations (including United Bank of Philadelphia and NOVA Bank ) were reminiscent of the limited-audience banks of the 1920s. However, the number of branch offices and the amount of deposits had become highly concentrated among national and international nameplates. Look carefully beyond those signs on the city’s old banking headquarters buildings, and you just might find the traces of their original tenants and the history of banking in Philadelphia.

Michael A. Martorelli is Director Emeritus at the investment banking firm Fairmount Partners in Radnor, and a frequent contributor to Financial History magazine. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- WSFS to acquire Philadelphia's Beneficial Bancorp in $1.5 billion deal (Delaware Business Now via WHYY, August 8, 2018)

- Wells Fargo will pay Philadelphia $10M to settle discriminatory lending lawsuit (WHYY, December 16, 2019)

- Regulators close Philadelphia-based Republic First Bank, first U.S. bank failure this year (Associated Press via WHYY, April 26, 2024)