Bank War

Essay

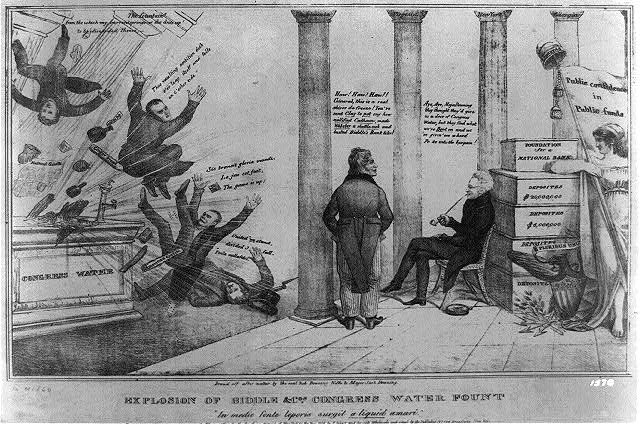

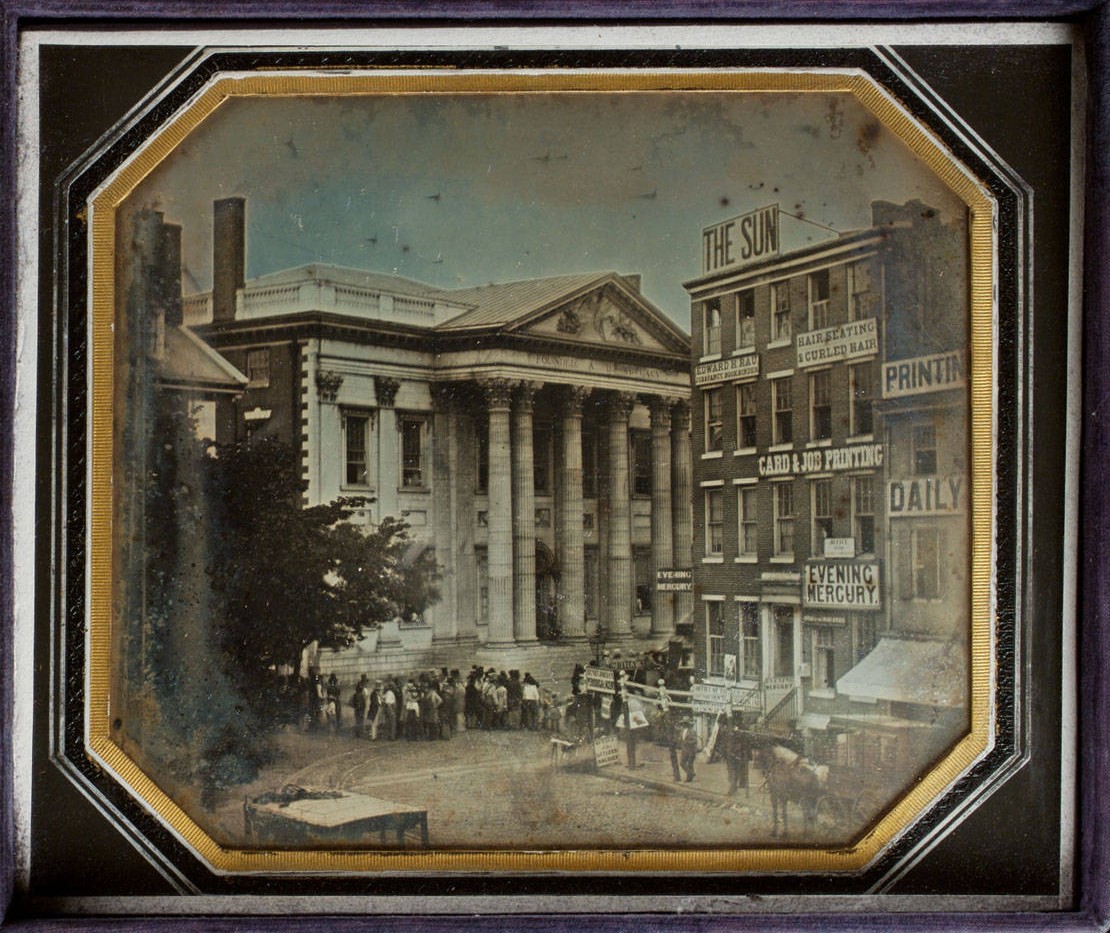

Conflict over renewing the charter of the Second Bank of the United States triggered the 1830s Bank War, waged between President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) and bank president Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844). Operating from its Parthenon-style building on Chestnut Street between Fourth and Fifth Streets in Philadelphia, the bank served as a reliable depository for federal money and provided a sound national currency. The expiration of its federal charter in 1836 virtually ended Philadelphia’s standing as the nation’s banking center, and New York’s Wall Street supplanted Chestnut Street as the America’s financial hub.

Congress issued a twenty-year charter for the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, with the government controlling twenty percent of the bank’s stock. Modeled after the First Bank of the United States, established in Philadelphia in the 1790s, the Second Bank handled all federal deposits and expenditures. The bank had a rocky start (overextension of loans helped trigger the Panic of 1819), but it became a dependable institution, and Biddle was generally considered a highly successful and respected leader. By the end of the 1820s, the bank had twenty-nine branches and conducted $70 million in business annually. Nevertheless, President Jackson’s first annual message to Congress in 1829 alleged corruption and condemned the bank as an unconstitutional entity. He favored hard money over bank notes, but also blamed the bank for the Panic of 1819, particularly for his personal losses.

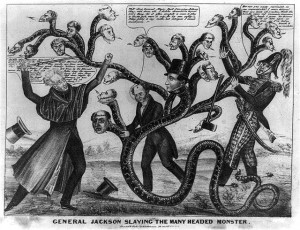

(Library of Congress)

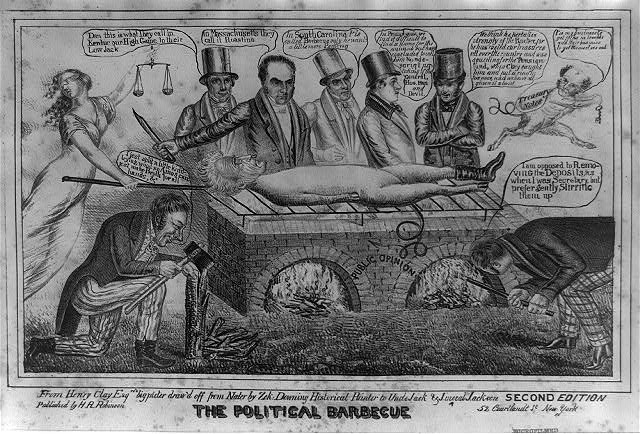

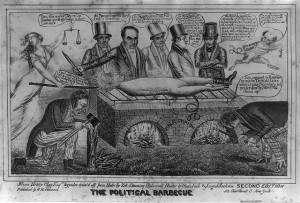

While Jackson, a Democrat, opposed the bank, National Republicans in Congress sought to renew the institution’s charter in 1832 (four years early), believing a veto would cost Jackson reelection. The House approved by 107-85 and the Senate by 28-20. Pennsylvania’s two senators and all but one of its twenty-five congressmen were among the bill’s advocates. The New Jersey and Delaware delegations were also strongly pro-bank. During congressional debates, pro-bank petitions came in from citizens of Philadelphia and Delaware County as well as from state banks, including fifteen from Pennsylvania. Despite nationwide support across various social groups, Jackson vetoed the bill.

Jackson handily won reelection in 1832, though his veto likely cost him votes. A majority of Philadelphians voted against Jackson (he did carry Pennsylvania); New Jersey voted in an anti-Jackson state legislature, but the state’s electoral votes ended up in Old Hickory’s column. He was still personally very popular. When Jackson visited Philadelphia on the first anniversary of his charter veto in June 1833, a reception in Independence Hall–just one block from the Second Bank–became so crowded with enthusiastic supporters that some had to escape the throng through open first-floor windows.

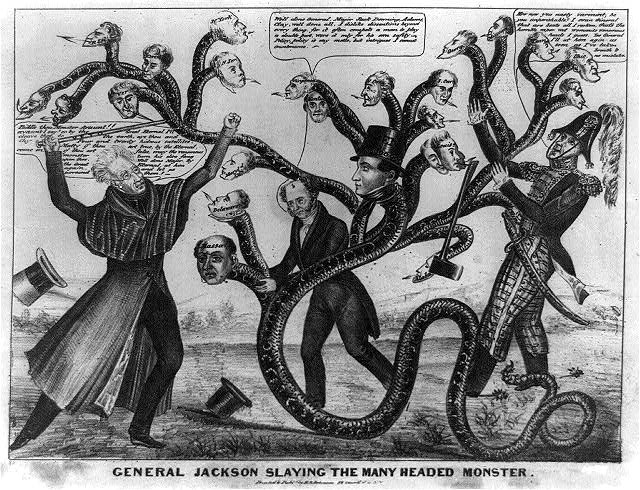

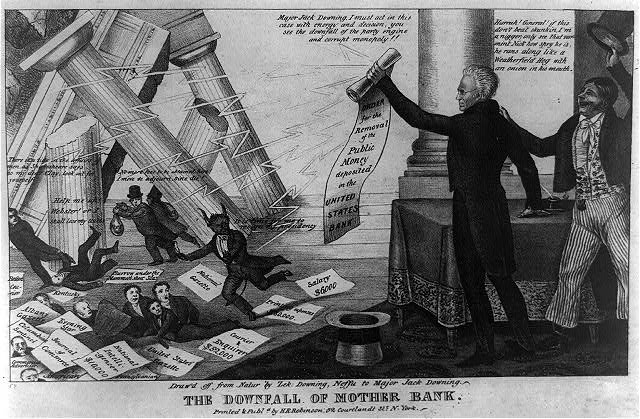

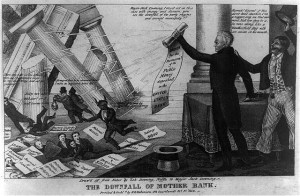

Jackson insisted that the bank was “trying to kill me,” and he vowed to destroy it at any cost. He believed his reelection a mandate and continued to portray the bank as a corrupt tool of foreign interests that worked against Americans. In 1833, President Jackson instructed his treasury secretary to withhold federal deposits, later transferring federal money to “pet banks” (state banks with Democratic ties). Jackson dismissed two secretaries before finding a willing accomplice in Roger B. Taney (1777-1864). In response, Biddle contracted the bank’s operations by calling in loans and exchanging state notes for specie to protect the institution and its investors. The bank’s board of governors unanimously concurred.

As the Second Bank limited its operations, however, an economic depression began, businesses closed, unemployment rose, and inflation reached one of its highest rates in U.S. history. Biddle did not have the capital to make payments on the national debt. The War Department forbade the bank from carrying out its responsibility of paying Revolutionary War pensions in an attempt to turn public opinion against it. Still, the bank initially lost little support and a new political party, the Whigs, emerged to challenge Jackson’s supposed tyranny. At the height of the Bank War, 1833-34, the Senate received 243 memorials calling for the return of federal deposits and only 55 petitions supporting the president’s actions. In January 1834, the Philadelphia Board of Trade issued a statement blaming the financial panic on the Jackson administration. Other Philadelphia banks also protested the president’s actions. Tensions grew to the point that wealthy, pro-administration Philadelphians found themselves excluded or expelled from social organizations. In Congress, the Whig-controlled Senate censured Jackson for his actions against the bank. Each side blamed the other for the turmoil.

Biddle ultimately relaxed the bank’s credit policies and the economic malaise lifted. The bank thus received the brunt of the blame for the previous years’ problems. The public turned against the bank, viewing its actions as vindictive. In 1834, Election Day riots occurred in Philadelphia, and the Whigs lost seats in Congress and the state legislature. Finally, in 1836, two weeks before the U.S. charter expired, the Pennsylvania legislature granted the bank a state charter. By the time Biddle retired in 1839, the bank was in poor shape. Over the following two years, when it could not pay its debts, the bank suspended and resumed specie payments twice, closing its doors permanently in 1841.

The Bank War cost Philadelphia and the nation a central bank, shifting the nation’s financial center to New York City. Thereafter, local banks lacked any regulating authority and the resulting speculation triggered panics through the rest of the century.

Andrew Tremel is an independent researcher and public historian at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History