North Philadelphia

Essay

Where exactly North Philadelphia begins and ends is a matter of debate. Even native Philadelphians have difficulty identifying the boundaries of this area of their city with precision. This is likely because so many of the neighborhoods located north, northeast, or northwest of Philadelphia’s center enjoy common histories and developmental patterns and consequently look a great deal alike. Before the 1682 arrival of William Penn (1644-1718) in North America, what is now North Philadelphia was covered with thick woods inhabited by Native Americans. Philadelphia’s establishment that same year began the area’s gradual transformation from acres of forests to blocks of homes, factories, churches, universities, and other institutions built to serve the area’s diverse inhabitants. These inhabitants included Native Americans, English colonists, and enslaved Africans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and waves of immigrants hailing from places as varied as America’s southern states; Northern, Southern, and Eastern Europe; the Caribbean; and Latin America in the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries.

The Lenni-Lenape Indians were the earliest documented inhabitants of the area that later became North Philadelphia. For thousands of years, the Lenapes occupied the banks of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, establishing several large settlements in and around the area that became North Philadelphia. These settlements included the Coaquannock or “Grove of Tall Pines” camp in the area that later became Laurel Hill Cemetery. Another camp called Nittabakonck, meaning “place that is easy to get to,” was situated near where the Wissahickon Creek empties into the Schuylkill River. Today, most of the remnants of these native peoples are deep underground, accessible only to archaeologists. However, a handful of North Philadelphia roads, including Frankford Avenue and Old York Road, roughly follow trails established by the Lenape and other Native American tribes centuries ago.

After William Penn founded Philadelphia as the capital of his New World colony, the forests that had sustained the Lenni-Lenapes slowly gave way to farms and estates. Hoping to attract people to his new “green country towne” and to encourage development in and around the city, Penn granted the initial investors in Philadelphia lots within the city but also “liberty lands” or “free lots” in areas north of the original city limits where farms could be established. Reminders of North Philadelphia’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century agricultural history exist in the form of landmarks like Judge William Lewis’s 1789 Strawberry Mansion (originally called Summerville), Fox Chase Farm (one of Philadelphia’s two working farms), and in place names such as “Northern Liberties.” Many property lines in North Philadelphia have origins in the farmsteads that were gradually developed as this area urbanized over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Post-Revolutionary War Development

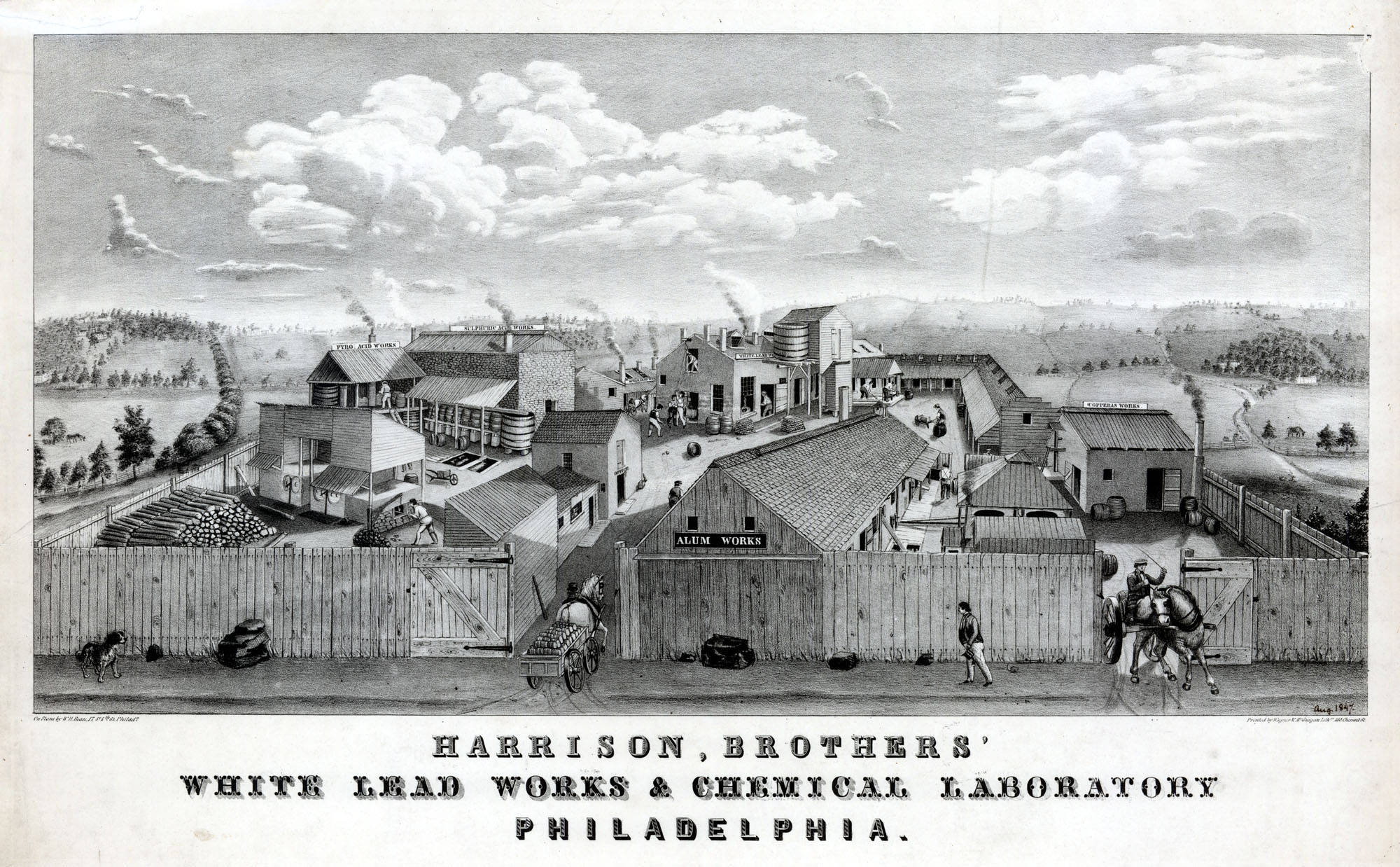

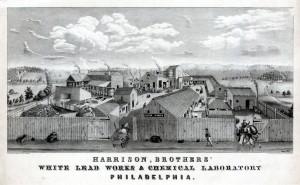

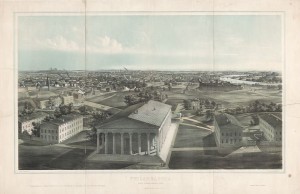

When the British occupied Philadelphia during the War for Independence, King George III’s soldiers ran their fortifications unhindered through the open ground along present-day Spring Garden Street. After the war, however, development pressure on the northern side of the city increased with the population boom that accompanied Philadelphia’s post-war position as the political, financial, and social capital of the United States. One of the first major developments in North Philadelphia following the Revolutionary War was an initiative to build a canal to link the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. If completed, the canal would have run along the present route of Pennsylvania Avenue to Broad Street on Philadelphia’s west side and would have bordered Spring Garden Street on the city’s east side. Due to lack of funds, however, this project floundered and the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, the Baldwin Locomotive Works, and various other industries filled in the canal’s right of way and the acres of open space along Philadelphia’s northern fringes. Not only did this part of the city offer industries convenient access to the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers and abundant space for growth, but the area was far enough removed from Center City to ensure that industrial smells and toxic chemicals would not interfere with central Philadelphia’s more genteel atmosphere.

The initial industrialization that took hold in North Philadelphia at the beginning of the nineteenth century laid the foundation for rapid changes later in the same century. Nineteenth-century maps of Philadelphia offer a compelling visual record documenting how urban expansion gradually eliminated the farms north of the city, replacing them with homes, factories, warehouses, workshops, and other institutions. An 1824 Map of Philadelphia published by William Allen shows heavily developed Northern Liberties and Kensington neighborhoods bordering the Delaware River, but sparsely populated blocks immediately north of the central city. Later maps of Philadelphia, such as W.H. Gamble’s 1887 Plan of the City of Philadelphia, show blocks of homes and factories stretching beyond Allegheny Avenue. The industrialization that overtook large swaths of open land in North Philadelphia quickly attracted residential development as workers drawn to factory jobs came to settle in the region. Companies such as Nicetown’s Midvale Steel, founded in 1867 as Butcher Steel; the large textile mills and tanneries of Kensington; Port Richmond’s Cramp Shipbuilders; and hundreds of other manufactories and cottage industries scattered throughout North Philadelphia created the vast array of goods and supported the mercantile culture that earned Philadelphia the nickname “The Workshop of the World.”

By the 1880s, North Philadelphia’s Broad Street neighborhoods competed with Rittenhouse Square and other fashionable districts for urban prestige. Along North Broad, the nouveau riche who were responsible for much of the industrial development of the surrounding neighborhoods constructed performance halls, social clubs, beautiful churches and synagogues, and proud, turreted homes of brick and brownstone. One of the most ostentatious of these North Philadelphia mansions, belonging to Peter A. B. Widener (1834-1915), stood on the corner of North Broad and Girard Avenues. This Germanic-style mansion represented the fortune that Widener acquired developing trolley lines, urban rail lines, and other public utilities that opened up great swaths of undeveloped land for urbanization. Wherever Widener’s car tracks or railroads were constructed, speculative row houses, twin, and detached houses quickly followed as trolleys made it possible for workers employed in Center City to commute from neighborhoods located outside of Philadelphia proper.

Development Bolsters City Coffers

Philadelphia’s rapid development eventually contributed to the city’s reputation as “corrupt and contented,” as Philadelphia’s 1854 Act of Consolidation helped bring money into city government coffers by incorporating the quickly developing areas outside the central city. Over time, this extra tax money often found its way into the pockets of city officials rather than being put back into Philadelphia’s treasury. This same growth also gained Philadelphia the moniker “the city of homes” as blocks of North Philadelphia filled with row houses built to accommodate a growing workforce that included thousands of immigrants, beginning with German and Irish families in the first half of the nineteenth century, followed by Russian, Eastern, and Southern Europeans in the second half. Amid its factories, mansions, and row houses, North Philadelphia acquired Mannenchoir halls and German beer gardens, Irish Catholic churches, Ashkenazi synagogues, Latvian social clubs, and various other religious, ethnic, and cultural institutions. These institutions served as community centers for the many immigrants whose Old World traditions helped them navigate the harsh realities they faced as they established new lives in Philadelphia.

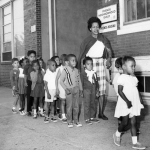

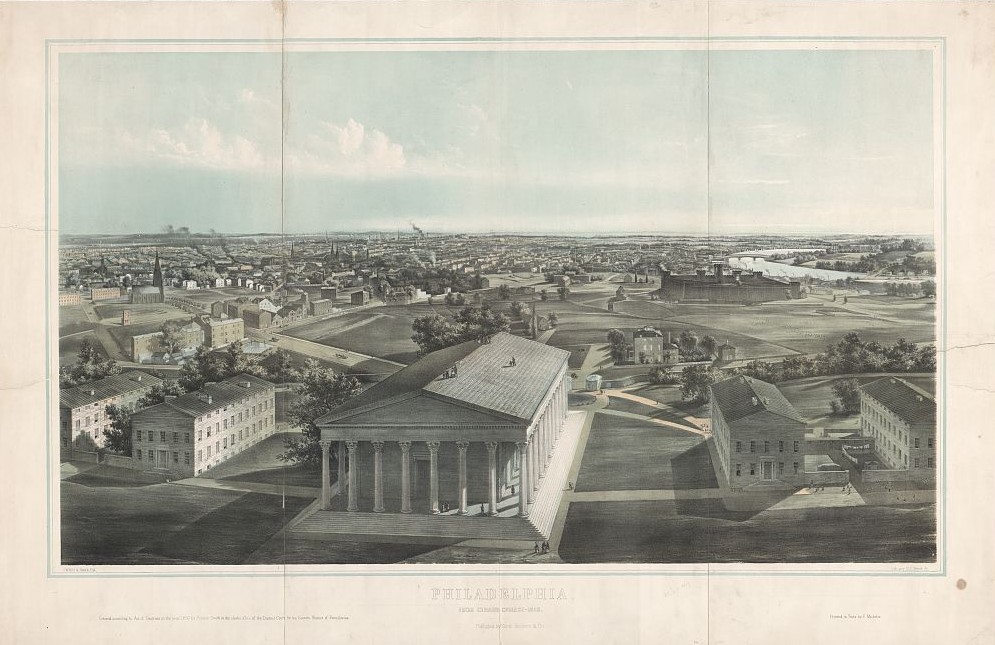

Philadelphia natives also invested in North Philadelphia to create other types of community centers with the intent of helping the area’s poorer residents better establish themselves into American society. One of the most notable of these institutions was Girard College, founded by the banker and philanthropist Stephen Girard (1750-1831), who provided millions of dollars upon his death in 1831 to establish a school for “poor, white, male” orphans. Several decades later in 1884, the Baptist preacher Dr. Russell Conwell (1843-1925) began to give lessons to working-class parishioners in the basement of Grace Temple Baptist Church located on North Broad Street. Temple University eventually grew from these efforts. In similar fashion, the Catholic Bishop James Fredric Wood (1813-1882) commissioned Brother Bernard Teliow (1828-1900), the principal of a local Catholic academy, to establish a school for Philadelphia’s often-persecuted Catholics. La Salle University was established in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood in 1863 but moved several times thereafter, eventually arriving at its present location on Olney Avenue in 1930.

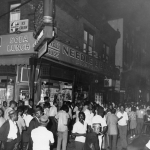

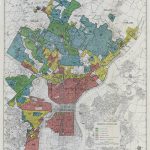

North Philadelphia retained a European immigrant flavor until the turn of the twentieth century, when African Americans from southern states began to migrate en masse to Philadelphia and other northern industrial centers, establishing many of North Philadelphia’s neighborhoods as important centers of Black culture. Black social groups formed throughout North Philadelphia and theaters like the Uptown and later the Freedom, both located on North Broad Street, promoted musical shows featuring gospel, jazz, and other types of performances aimed at African American audiences. North Philadelphia also became a center of Black activism as the area’s African American residents fought for better representation and working conditions and against redlining practices that refused housing loans to individuals who lived in areas deemed to be “high risk.” Nevertheless, white flight from North Philadelphia led to increased segregation in the area during the 1950s and the 1960s, decades that also saw the shuttering of many of the factories that North Philadelphia’s residents had long depended upon for work. Each factory closing increased stress on neighborhoods already marred by poverty and growing racial tensions. A low point for North Philadelphia came in 1964 with the Columbia Avenue Riot, which arose out of conflicts between police and North Philadelphia’s African American community. The riots resulted in hundreds of injuries, arrests, and looted businesses, many of which never reopened.

Urban Renewal in 1990s

During the last half of the twentieth century, blocks of decaying buildings and nearly deserted streets registered the impact of the social and economic fraying suffered by many of North Philadelphia’s neighborhoods. The general disregard shown North Philadelphia by private investors from the 1950s into the 1990s levied a devastating blow to this sector of the city. Attempts at renewing North Philadelphia did come in the form of federally funded housing projects like the Richard Allen Homes built in 1941, Cambridge Plaza built in 1957, and the 1967 high-rise Norman Blumberg Projects—projects which, at the time they were built, were hailed as progressive solutions to urban problems. Nevertheless, by the 1980s, many of these projects had fallen into disrepair and become centers of crime and drug activity. Starting in the 1990s, several of these projects were refurbished or, in the case of the Richard Allen Homes, completely torn down and replaced with detached suburban-style townhouses. These homes have improved neighborhood conditions in sections of North Philadelphia but have also been criticized for not accommodating the city’s poorest residents and for being architecturally incongruent with the row houses that dominate much of North Philadelphia.

Numbers from the 2010 census documented that North Philadelphia’s legacy of constant change continued. The northern neighborhoods nearest to Center City, including Spring Garden, Northern Liberties, and Fishtown witnessed rapid gentrification as urban professionals occupied newly built townhouse complexes and patronized the bars, restaurants, and galleries that slowly replaced their decaying factory buildings or abandoned lots. According to the 2010 census, Northern Liberties and Fishtown experienced the highest population increase in Philadelphia (a 24.7 percent increase from 2000 to 2010). At the same time, other North Philadelphia areas attracted job-seeking Puerto Ricans and Dominican and South American immigrants. Latin restaurants, bodegas, cultural institutions, and street murals in Spring Garden, Fairhill, Kensington, Frankford, Olney, and most especially in the North Philadelphia “Centro de Oro” area (located around the intersection of Fifth Street and Lehigh Avenue), document the strong Latino influence that has rooted in large swaths of North Philadelphia.

Some North Philadelphians openly bemoaned the waves of change that beset their neighborhoods, fearing that familiar characteristics would be lost in the process. Many others recognized, however, that North Philadelphia’s history revolves more around transformation than around constancy. Indeed, it is this constant transformation that has made North Philadelphia into one of Philadelphia’s most textured and fascinating areas—an area whose built environment not only registers Philadelphia’s own poignant story but also many of the historical trends that have informed centuries of broader American history.

David Amott earned his Master’s and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Delaware in art and architectural history. While working on these degrees, he researched several immigrant churches in North Philadelphia for the Historic American Building Survey. This experience allowed him the opportunity to become familiar with and to fall in love with North Philadelphia and its rich history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Two North Philly grade schools to undergo massive staffing changes in hopes of 'turnaround' (WHYY, March 11, 2014)

- Philly pizza shop owner loses land but not livelihood to eminent domain (WHYY, April 25, 2014)

- North Philly parents suspicious of postponed charter school election (WHYY, April 29, 2014)

- North Broad renaissance underway, Philly leaders say (WHYY, May 14, 2014)

- Touring a North Philly Renaissance school, a microcosm of the city's education debate (WHYY, June 4, 2013)

- History of Philly rests under I-95 (NBC 10, July 18, 2014)

- 50 years later the legacy of 1964 riots lingers (WHYY, August 12, 2014)

- Remembering the 1964 riots in North Philadelphia [photos] (WHYY, August 26, 2014)

- Cultivating healthy eating habits at North Philly vegetable garden (WHYY, September 2, 2014)

- New $19 million wellness center aims to transform one of Philly's most struggling neighborhoods (WHYY, March 16, 2015)

- 'New PHA' lays out ambitious plans to redevelop pocket of North Philly (WHYY, June 4, 2015)

- Philly and developer planning project to rise in Logan, site of sinking homes (WHYY, October 9, 2015)

- Parsing the Housing Authority's plans for Sharswood (PlanPhilly, January 14, 2016)

- Remaking Sharswood: Taking a neighborhood through eminent domain in the name of ‘transformation’ (PlanPhilly, March 7, 2016)

- A garden, a redevelopment plan, and a fight over who owns a neighborhood (WHYY, May 24, 2016)

- Watching the DNC from the other side of Philadelphia (WHYY, July 28, 2016)

- Celebrating 30 years of uplifting families with better housing in North Philadelphia (WHYY, October 14, 2016)

- Site Visit: Orinoka Civic House and walking tour with NKCDC (PlanPhilly, May 5, 2017)

- Philadelphia Housing Authority relocating headquarters to North Philly (WHYY, June 21, 2017)

Links

- Fishtown: Philadelphia Neighborhoods (Youtube.com)

- Greensgrow Farms: Fishtown & Kensington, Sustainable and Green (PhilaPlace.org)

- Historical Society of Frankford

- How Philly Got Flat: Piling it on at the Logan Triangle

- A Long-Lost Monument to Philadelphia's Iron Age

- The Northern Liberties: Building on "Ruins," a Walking Tour Guide (PhilaPlace.org)

- Northern Liberties Then & Now (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Origins of the City Branch? Canal, Natural & Man-Made (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Richard Allen Homes (PhilaPlace.org)

- Digging I-95: The Archaeology of Northern Liberties, Kensington-Fishtown, and Port Richmond