Green Country Town

Essay

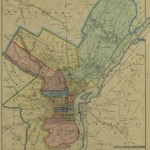

How often have you heard people proudly call Philadelphia a “greene country towne,” quoting William Penn’s evocative description of the city he founded? Along with “city of brotherly love” – another catchy Penn coinage – the phrase ranks as the granddaddy of all municipal brands, pre-dating “Big Apple” and “Big Easy” by almost three centuries. Penn didn’t just talk the talk: when he laid out the street grid, he gave Philadelphia the gift of five public squares.

Yet it would be wrong to assume from this history that Penn instilled Philadelphia with a commitment to public space. From the city’s earliest days, its parks have been underfunded and under-appreciated. Instead of valuing them as places for leisurely enjoyment, Philadelphia has too often treated its parks as workhorses that can be harnessed to practical municipal goals, especially economic development. Philadelphia’s beautiful parks have continually defended themselves against private interests, parochial concerns, and municipal parsimony in a never-ending struggle for survival.

While Penn envisioned Philadelphia as a lush American Eden, he was, at his core, a real estate developer – among America’s first. He recognized that the inclusion of open space could help make his urban experiment more appealing to buyers. The five squares were useful because they helped relieve the regularity of Philadelphia’s street grid, while increasing the value of nearby house lots. But deep down, Penn didn’t really like the idea of parks. As historian Elizabeth Milroy has noted, as a young man Penn had written articles warning of the ungodly temptations of public gardens. Meditative strolls had their place, he acknowledged, but such unproductive fun as “bowling greens, Hors races…and such like Sports” was to be avoided at all cost. Ultimately, Penn’s need to move real estate overrode his moral reservations. That pragmatic approach has informed the city’s attitude toward its parks ever since.

Penn was suspicious of cities in general. His attitudes were shaped, in part, by the back-to-back disasters that befell London during his youth – the outbreak of plague in 1665, followed by the massive fire in 1666 that destroyed the city’s medieval center. When it came time to lay out Philadelphia’s grid with surveyor Thomas Holme in 1683, Penn was determined to improve upon London’s plan. To limit the spread of disease and fire, he insisted that Philadelphia’s houses should be set on big lots and arrayed along wide streets. Penn declared that Philadelphia would be a “greene Country Towne which will never be burnt, and always be wholesome.”

Five Squares With a Funding Dilemma

Having bequeathed those five public squares to the city as part of the plan, Penn then established the great Philadelphia tradition of not funding them. Because no money was allotted for turning the wild blocks into landscaped parks, Philadelphians quickly developed the habit of using their public spaces to dump trash. They became convenient places to hang criminals and bury the poor. It wasn’t until 1820 that the city government agreed to take responsibility for their upkeep. Philadelphia’s reluctance to financially support its parks would become a regular theme.

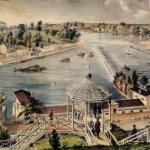

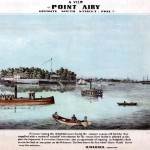

In the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia began to accumulate the large tracts that would eventually become Fairmount Park. What motivated the purchases? The appeal of Sunday carriage rides along the Schuylkill River was certainly one factor, but what really spurred the city was the practical need to protect the city’s water supply from polluting industries that clustered upriver. Once again, Philadelphia saw no reason to hire a landscape architect to give the park form, unlike other large cities that clamored for the services of Frederick Law Olmsted and other planners. Philadelphia did fund some improvements in the years leading up to the Centennial Exhibition, as Fairmount Park grew to 2,600 acres, but contributions fell as soon as the event was over. Milroy calculates that in the 1870s the city was spending roughly $83 an acre, a pittance compared to the $916 that New York lavished on each of Central Park’s 862 precious acres.

Today Philadelphia has the unfortunate distinction of spending less on its park system than any big city in America. Fairmount Park has not seen its budget increase in more than two decades. In 2010, the operating budget for Fairmount Park’s 9,200 acres sank to a woeful $12.6 million. Consider: New York devotes $8 million to the four acres of Bryant Park alone. Chicago, which imposes a special tax assessment to keep its green spaces looking spiffy, spends 30 times as much as Philadelphia on parks.

One reason that Philadelphia’s parks are underfunded is because they are not seen as having any practical value. Like Penn, today’s public officials still think of parks as a tool – rather than as an amenity where residents can relax or play games. It is no accident that we often refer to green space here as a “resource,” a word that suggests the potential for money-making exploitation, as if a park were as fungible as reserves of oil and timber. It’s no wonder that the city faced little opposition in the 1960s when it sliced off a beautiful stretch of its Schuylkill River frontage to build a highway. Even nowadays when the city adds parkland, it is often with a practical policy objective in mind. The two biggest park projects of the last half-century – Penn’s Landing and Independence Mall – have been viewed as part of a strategy for marketing the city to tourists. It’s telling that neither space includes that most basic of residential amenities: a children’s playground.

Parks vs. Business Interests

This way of thinking about parks cannot simply be ascribed to the misjudgments of the urban renewal years. When Fox Chase Cancer Center needed room for expansion in 2008, the John F. Street Administration offered to sell the hospital twenty acres from Burholme Park, a popular park in the Northeast. His successor, Mayor Michael Nutter, continued to push the deal until it was overturned in court. The judge had to remind the city that Robert Ryerss – a wealthy Quaker, like Penn – had donated Burholme Park’s sixty acres “for the use and enjoyment of the people forever.” Despite this reprimand, Mayor Nutter came up with a plan two years later to trade away more parkland, this time to help out a tour boat operator called Ride the Ducks. The company called for cutting a trench through the popular Schuylkill Banks recreation trail to make it possible for boats carrying kazoo-tooting tourists to access the river. The scheme was dropped only after a public outcry.

Mayor Nutter certainly would not consider himself to be anti-park. Within months of announcing his intention to hand over a section of Schuylkill Banks to the Ducks, he released a commendable scheme to enlarge the Fairmount Park system by converting the city’s asphalt schoolyards to mini parks. Of course, the plan has a practical benefit that goes beyond providing a softer, more natural environment for kids to play catch. The green surfaces will slow water run-off, thus reducing the need to add costly sewer pipes.

Shortly after this proposal to green 500 acres was announced, the new census confirmed what many in Philadelphia had long suspected: The city’s population was growing again, for the first time in half a century. As energy prices rise, dense urban centers like Philadelphia are well placed to attract more new residents. But, in the age of the internet, the city will have to compete to keep its residents satisfied, and that means providing high-quality parks and amenities. After three centuries of describing itself as a green country town, it’s time for Philadelphia to live up to its brand.

Inga Saffron is the Architecture Critic at the Philadelphia Inquirer. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.

Map

Timeline

Links

- Philadelphians reflect on the value of parks, video by WHYY's Newsworks

- Recording of Greater Philadelphia Roundtable discussion program, Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, May 10, 2011

- "Green Country Town" Discussion Summary, Greater Philadelphia Roundtable, May 10, 2011

- $11 million in foundation grants announced for five parks (PlanPhilly via WHYY, March 16, 2015)

- Reclaiming public space for Philly's 8th annual Park(ing) Day (PlanPhilly via WHYY, September 21, 2015)