Laurel Hill Cemetery

By Thomas H. Keels | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

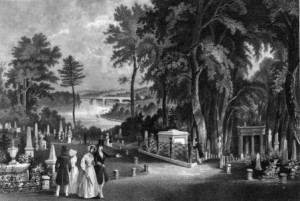

Founded in 1836 as an alternative to the overcrowded churchyards of rapidly growing Philadelphia, Laurel Hill Cemetery was the first rural cemetery for the city and the second in the United States. With monuments designed by the era’s most prominent sculptors and architects, it served as elite Philadelphia’s preferred burial place for over a century. More than a cemetery, Laurel Hill became an outdoor art museum and tourist attraction and provided a prototype for Fairmount Park.

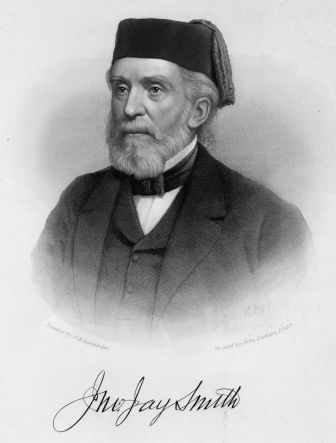

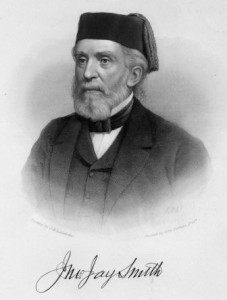

The idea for Laurel Hill originated in 1835, when John Jay Smith (1798-1881), a Quaker editor and horticulturist, joined forces with several other Philadelphians to establish a rural cemetery similar to those in Europe, like Père Lachaise outside Paris. Products of the period’s Romantic philosophy, rural cemeteries were meant to beautify death with picturesque landscapes filled with classical monuments and to replace unhygienic urban churchyards. The first rural cemetery in the United States, Mount Auburn, was founded in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1831.

Before the founding of Laurel Hill, most Philadelphians were buried in one of three places, depending on their social and economic status. Wealthy landowners could rest in private family plots at their country estates, like the Logan Burial Ground at Stenton. The poor, along with religious and racial minorities, were often banished to the Potter’s Fields that, starting in 1825, were reclaimed as Washington Square, Franklin Square, and Logan Square. While a few alternatives existed (such as workers’ association cemeteries or small private cemeteries like Ronaldson’s), most Philadelphians favored the burial grounds associated with their churches.

Between 1800 and 1830, the population of Philadelphia – then bounded by Vine and Cedar (South) Streets – grew 133%, from 81,000 to 189,000. By the 1830s, many urban churchyards were overcrowded, neglected, and under development pressure. At the Friends’ Burial Ground at Arch and Fourth Streets, in use since 1701, nearly 20,000 bodies were crammed into less than half a city block. John Jay Smith’s inability to locate his daughter’s grave there, after construction on the adjacent meeting house, was a major impetus in his decision to found Laurel Hill.

Elevation Ideal for a Cemetery

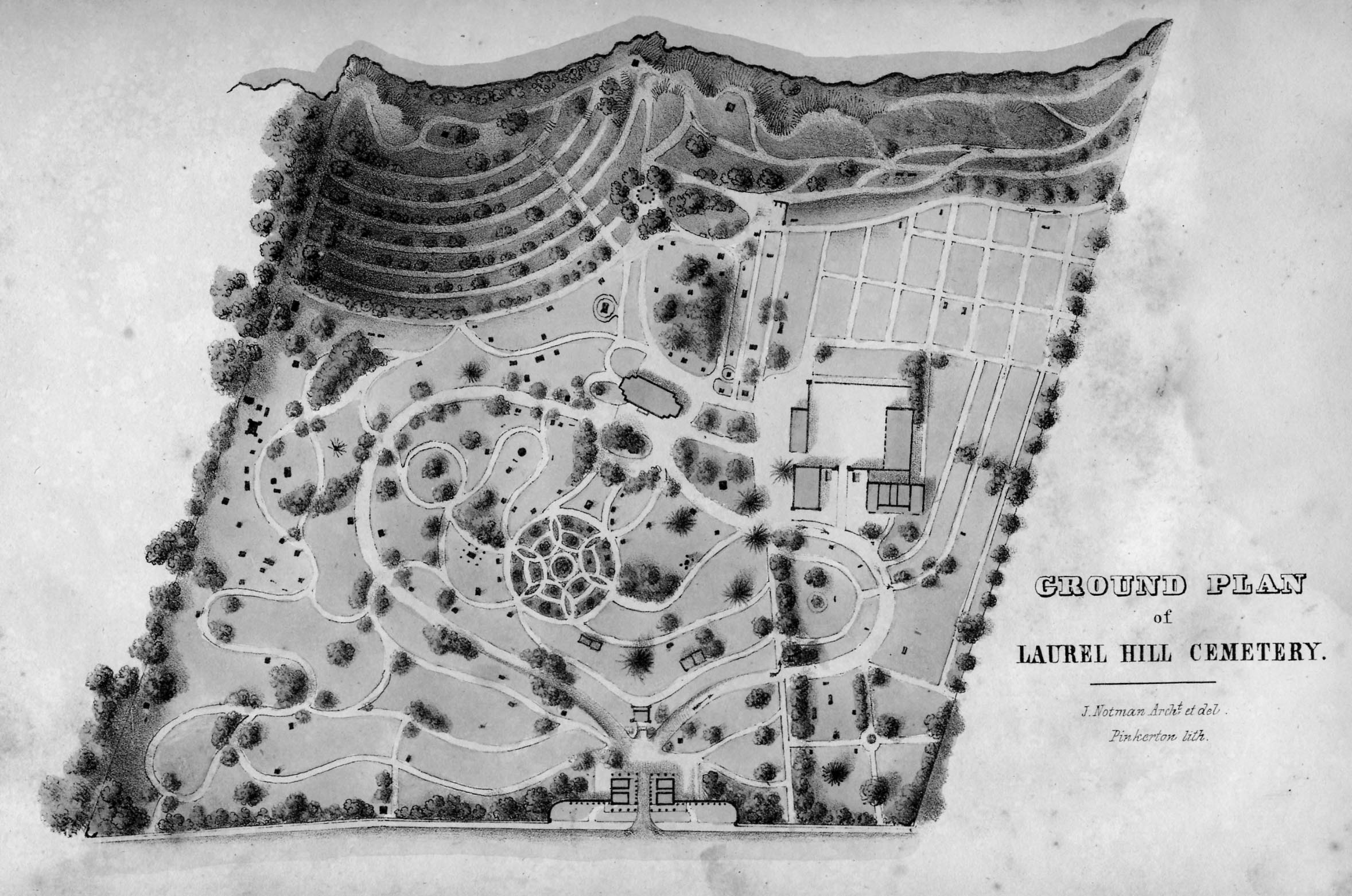

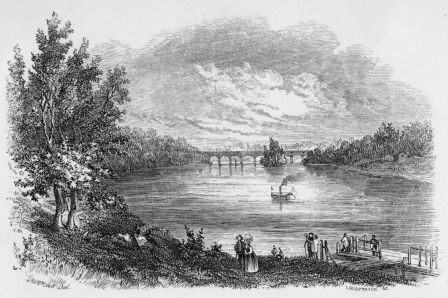

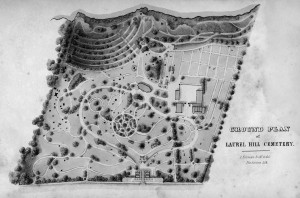

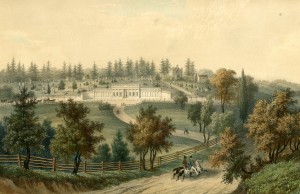

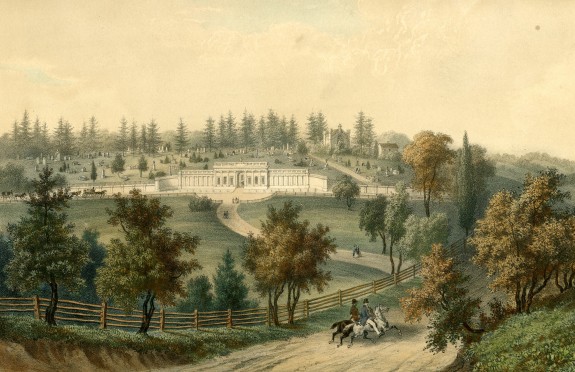

In early 1836, Smith and his associates acquired Laurel Hill, a 32-acre estate on the east bank of the Schuylkill River, near the Falls of Schuylkill (later East Falls). Rising 100 feet above the river, Laurel Hill’s well-drained soil made it ideal for a cemetery. Its remote location, nearly four miles northwest of Vine Street (then Philadelphia’s northern boundary), seemed likely to remain bucolic indefinitely.

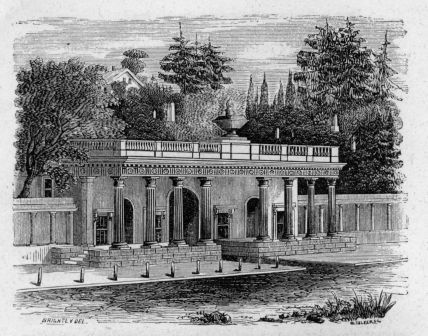

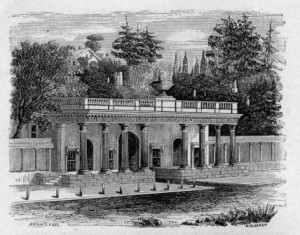

John Notman (1810-1865), a Scottish immigrant who later designed the Athenaeum and St. Mark’s Church, created the cemetery’s imposing Roman Doric gatehouse on Ridge Avenue. Laurel Hill’s ground plan, loosely based on Kensal Green outside London, is usually attributed to Notman, although some scholars have named local surveyor Philip M. Price as the designer. Burial lots were priced at $50 to $150, limiting interment to the city’s wealthier classes. The average lot size of 120 square feet allowed not only for burial of many more family members than a small urban churchyard lot but also for the erection of an imposing monument by Notman, William Strickland (1788-1854), or another noted architect.

Laurel Hill’s managers attempted to make the cemetery an American pantheon by relocating famous Revolutionary figures from their original burial sites. Among those reburied at Laurel Hill were Continental Congress Secretary Charles Thomson (1729-1824), taken from his wife’s Lower Merion estate, Harriton; David Rittenhouse (1732-96), astronomer and first Director of the Mint, removed from his family farm in Germantown; and Hugh Mercer (1726-77), hero of the Battle of Princeton, whose remains were disinterred from under the central aisle at Christ Church and transported up the Schuylkill on a funeral barge.

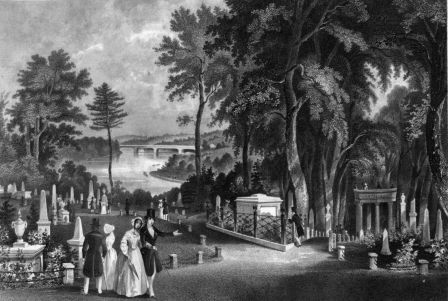

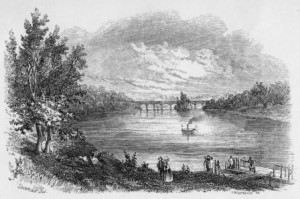

Soon, Laurel Hill grew popular among Philadelphia’s elite as both a burial site and tourist attraction. In 1844, Godey’s Lady’s Book noted that Laurel Hill served as the resting place “of our most responsible families in every walk of life.” By then, more than 900 families owned lots there. In addition, nearly 30,000 people visited Laurel Hill each year, seeking to escape the city’s heat and crowds for its peaceful landscape. Some traveled from Philadelphia along Ridge Avenue via carriage or horse-car, but most preferred a scenic steamboat cruise from the Fairmount Water Works up the Schuylkill River to the Laurel Hill landing at Hunting Park Avenue. To minimize crowds, Laurel Hill’s managers closed the cemetery to all except lot-holders on Sunday, the one day when working-class Philadelphians would be free to visit.

Laurel Hill’s Expansion

Between 1849 and 1863, Laurel Hill’s managers acquired three additional tracts of land, enlarging it to more than 90 acres. Laurel Hill’s success sparked a rural cemetery boom. The Woodlands, Laurel Hill’s chief competitor for Philadelphia’s upper crust, was founded on the Hamilton estate in West Philadelphia in 1840. By 1876, there were more than twenty rural cemeteries in the Philadelphia region, many catering to specific religious and racial groups. Among them were Cathedral and New Cathedral Cemeteries for Catholics; Lebanon and Olive for African Americans; and Mount Sinai and Montefiore for Jews. Across the Delaware River in Camden, New Jersey, Harleigh Cemetery became the final resting place of poet Walt Whitman (1819-92).

While safeguarding the city’s water supply was the primary factor behind the founding of Fairmount Park in 1867, park advocates also cited the crowds of visitors to rural cemeteries as another reason to create an additional, vast public preserve. Eli Kirk Price (1797-1884), one of the park’s original commissioners, was also a founder of The Woodlands. Along with other benefits, he hoped that a public park would reduce the number of visitors to his cemetery. In his original design for Fairmount Park, James Clark Sidney (c. 1819-81) incorporated many elements from his layout of South Laurel Hill in the 1850s.

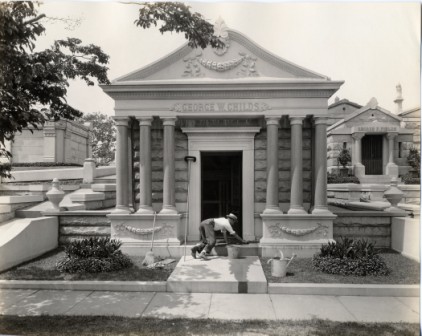

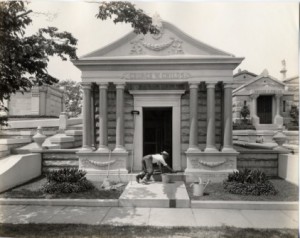

During and after the Civil War, Laurel Hill became the resting place for hundreds of military figures, including George Gordon Meade (1815-72), leader of the Union Army at Gettysburg. Laurel Hill also attracted the men dominated local politics and business after the Civil War, including saw manufacturer Henry Disston (1819-78), publisher George W. Childs (1829-94), and traction magnate P.A.B. Widener (1834-1915). Many of these oligarchs were laid to rest in imposing mausoleums along “Millionaire’s Row,” overlooking Hunting Park Avenue.

By 1900, the overcrowded cemetery was hemmed in by an industrial neighborhood on its north and east sides, and by Fairmount Park to its south. Seeking alternative resting places, many Philadelphians turned to suburban cemeteries like West Laurel Hill, founded by John Jay Smith in Lower Merion in 1869. Laurel Hill’s decline accelerated after World War II, when the cemetery and surrounding community were beset by financial instability, neglect, and vandalism.

In the 1970s, concerned Philadelphians intervened. In 1978, the Friends of Laurel Hill Cemetery was founded by Drayton Smith (a direct descendant of John Jay Smith), his wife, Jane, and historian John Francis Marion. Marion began the popular tradition of nighttime Halloween tours, and the Friends successfully nominated the cemetery for the National Register of Historic Places and for designation as a National Historic Landmark. They raised funds to restore landscaping, public buildings, and hundreds of monuments. By the early twenty-first century, thousands of visitors each year attended public programs at Laurel Hill, including concerts, theatrical performances, photo workshops, films, ghost hunts, car shows, astronomy nights and walking tours. Like the Philadelphians who journeyed to the rural cemetery in the nineteenth century, visitors once again used the cemetery for recreation and relaxation amidst its beautiful landscape.

Thomas H. Keels is a local historian and the author or coauthor of six books on Philadelphia, including Forgotten Philadelphia: Lost Architecture of the Quaker City (Temple University Press, 2007). His latest work, Sesqui! Greed, Graft, and the Forgotten World’s Fair of 1926, a study of the ill-fated Sesquicentennial International Exposition, will be published by Temple in early 2017. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Friends of Laurel Hill Cemetery

- West Laurel Hill Cemetery

- PhilaPlace: Final Resting Place (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: A Cemetery for Millionaires (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Building a City of the Dead: The Creation and Expansion of Laurel Hill Cemetery (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)