Fairmount Water Works

By Lynn Miller

Essay

For more than two centuries, Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works provided two vitally important, but different, services to the city. The first began when Philadelphia’s municipal water system—the first of its kind anywhere in the modern world—was moved to Fairmount and enlarged. Thanks to its charming design and placement beside the bucolic Schuylkill River, its second and more enduring role began shortly thereafter when the riverbank below Fairmount became the birthplace of what would become the largest landscaped urban park in North America.

Philadelphia had constructed its first waterworks in 1799 at Centre Square, later the site of City Hall. Steam engines pumped fresh water from the Schuylkill into a tunnel along Chestnut Street to the pumping station, from which it was distributed through bored-log pipes throughout the city. Yet, it soon became clear that the plant and its site were too small to accommodate the rapidly growing city. The engines broke down frequently, and the reservoir had to be constantly replenished, at great expense, to keep them running. Within a dozen years, city officials recognized the need to expand the plant significantly if they were to continue to provide clean water to the rapidly growing city.

By 1811, a young engineer, Frederick Graff (1775-1847), was superintendent of the waterworks. He recommended that a new and much larger facility be built at Fairmount, just to the northwest of the city boundary and at the Schuylkill’s edge. Water could be pumped up to reservoirs to be constructed on the hill’s summit. From there, gravity would do the rest, allowing water to flow through pipes down into the city. The Watering Committee agreed, a plot of land was acquired at Fairmount, and construction began on August 1, 1811. The initial structure was an engine house, built to hold the two steam engines, pumps, and boilers required to raise Schuylkill water up to the reservoirs. Graff’s design was for a building that might be mistaken for one of the grand country villas built in the previous century along the river bank by affluent citizens as summer retreats.

The new facility greatly increased the water supply to the city, but still at considerable cost. In 1819, Graff estimated the bill to be almost $31,000 annually for each of the two engines, since 3,650 cords of wood had to be burned to fuel them, in addition to the costs of their staffing and maintenance. He proposed that the city should abandon the expensive steam technology and build a spillway dam at an angle across the river so that water power could drive the pumps. Once agreed to, construction began in 1819. When completed two years later, the dam was the longest in North America at 2,008 feet. A mill house for the new water wheels was constructed at river’s edge with its terrace roof just above the level of the riverbank. Behind it, a channel was dug out of the rock to create a forebay so that water would flow into it from above the dam. It would then fall down through flumes to turn the waterwheels, the excess returning to the river below the dam. The change to water power proved very successful financially. The high point for revenues came in 1844 when the Fairmount Water Works supplied an average of 5.3 million gallons of water per day to its 28,082 customers at a cost of $29,713, but returned $151,501 to the city treasury.

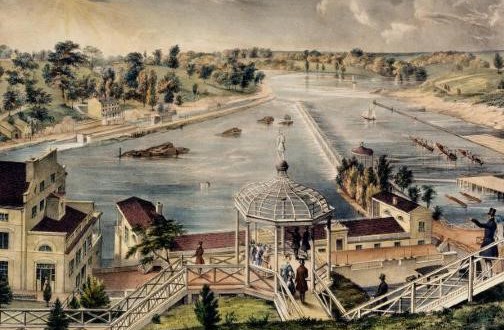

Meanwhile, a leisure-time destination had been born. Graff placed two little administrative buildings in the form of Classical temples at each end of the terrace roof of the mill house. Visitors could cross to it via a pedestrian bridge, take in the roar of waters spilling over the wheels, then climb to a small pavilion at the top of Fairmount to inspect the reservoirs and the river. What had been a quarry just below the engine house, then the site for storing the wood to fuel the steam engines, was landscaped between 1829 and 1835 to become the South Garden. A columned gazebo was built at the eastern end of the dam’s spillway and ornamented with a carved wooden eagle. Stages and boats from the foot of Chestnut Street brought visitors up from the city. Once the old steam engines became obsolete, they were sold for scrap, and the engine house was turned into a public saloon. A columned porch added to the riverside harmonized with the little temples on the mill house roof.

The Act of Consolidation of 1854 brought some 300,000 residents of what had been outlying districts within the borders of Philadelphia, making expanded facilities at the waterworks imperative. Three years before Philadelphia’s expansion, a new hydraulic turbine was installed, which increased the volume of water available. Since there was no more room for reservoirs atop Fairmount, a new one was built at Corinthian Avenue, which could receive water flowing from a water tower constructed higher on Fairmount. Starting in 1859, a new mill house was built into the mound dam at an angle to the old one to accommodate three new turbines. Its roof also became a terrace from which visitors could view the river. Finally, from 1868 to 1872, the old mill house was again altered to make room for an additional set of three turbines. Frederic Graff Jr. (1817-1890), chief engineer of the city’s Water Department, extended parts of its river wall eight feet into the river. He used a design his father had created nearly fifty years earlier to construct a large columned pavilion in the center of the enlarged terrace roof. He placed two small entrance houses between it and the earlier small pavilions at either end.

The city had acquired the former estate of Robert Morris, Lemon Hill, in 1845. Its mansion stood on the summit of the height just to the west of Fairmount. Yet, little effort was made to join the two parcels in an enlarged public park until after the Civil War, even though the combined acreage was officially named Fairmount Park in 1845. But finally, in 1867, Pennsylvania’s Public Law 547 authorized Philadelphia, through the newly created Fairmount Park Commission, to acquire land along both sides of the river “as open public ground and Park for the preservation of Schuylkill water and of the health and enjoyment of the people forever.” By 1876, the city had acquired some three thousand acres, including the Wissahickon Valley, carrying the boundaries of Fairmount Park to the northwest city limits.

When the city and its suburbs consolidated in 1854, a number of steam-generated pumping stations came under the jurisdiction of city officials. For a time, the greater economy of water power meant that the Fairmount facility continued to benefit the city financially. Yet within decades it became clear that industrialization along the river, including that well beyond the city’s limits, had polluted the river irremediably. In 1890, Philadelphia suffered a terrible outbreak of cholera and typhoid. Since no room existed at Fairmount to build the kinds of chemical treatment plants that were coming into being elsewhere in the city, its waterworks were decommissioned in 1909. The two mill houses were transformed into a city aquarium in 1911. For a time, sea lions cavorted in the forebay. But in 1923, the forebay was filled in, its pedestrian bridge buried intact. Along with maintenance, attendance declined at the aquarium after World War II. Its life ended in 1962, and a public swimming pool was installed in the new mill house. Flooded by Hurricane Agnes in 1972, the pool closed the following year. For nearly two decades, the waterworks sat idle.

Starting in 1974, the Junior League began to lead an effort to raise the funds necessary to restore the waterworks. In that year, the league gave the city $24,000 to protect the buildings from the weather. Responding to league appeals, the Fairmount Park Commission and the Water Department joined the effort. In 1976, the U.S. secretary of the Interior designated the site a National Historic Landmark. By 1988, advocates had raised $23 million and restoration began. By the time it was largely completed twenty years later, the transformation was nearly complete. The Fairmount Water Works Interpretive Center was installed in the old mill house; the engine house became a fine restaurant; the South Garden, cliffside paths, and esplanade were returned to their appearance in the mid-nineteenth century. Even the long-gone Rustic Pavilion was recreated in steel to overlook the Water Works from near the summit of Fairmount.

As early as the 1820s, the Fairmount Water Works had become a pleasure ground. The effort to protect the city’s water supply led serendipitously to the creation of one of America’s largest urban parks as an enduring legacy of the modern world’s first municipal water system. The Water Works excited the world early in the nineteenth century with their beauty and economy of operation. For a time in the second half of the twentieth century, their condition grew perilous from neglect. Subsequently restored to iconic status as one of the most recognizable images of Philadelphia, the Water Works became the Delaware River basin’s official watershed education and gateway center for the Schuylkill River National and State Heritage Area.

Lynn Miller is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Temple University. He is the author of, among other works, Global Order: Values and Power in International Politics, Crossing the Line (a novel), and the co-author (with James McClelland) of City in a Park: A History of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park System. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Audacious new plan unveiled for Fairmount Park (WHYY, May 14, 2014)

- 'One Man's Trash' puts year-long Wissahickon cleanup effort on display at Fairmount Water Works (WHYY, April 21, 2015)

- Fairmount Park plans for the future (WHYY, May 4, 2015)

- "City in a Park" offers history--and stunning images--of Fairmount Park (WHYY, November 25, 2015)

- Plan to install replicas of early Water Works sculptures approved by Art Commission (WHYY, June 15, 2017)

Links

- Fairmount Water Works (Philadelphia Water Department)

- Fairmount Water Works

- PhilaPlace: The Fairmount Water Works - Disease and the City's Water Supply (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Frederic Graff Jr. (Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, Athenaeum of Philadelphia)

- Schuylkill River National and State Heritage Area

- Fairmount Park (Visit Philadelphia)

- The Wissahickon Gorge (Visit Philadelphia)