Schuylkill River

Essay

Extending some 130 miles in a generally southeasterly direction from its source at Tuscarora Springs in the anthracite coal region of Schuylkill County to its point of confluence with the Delaware River in Philadelphia, the Schuylkill River has played a central role in shaping the character and aspirations of Philadelphia and the regional hinterland through which it flows. The river’s watershed of about two thousand square miles lies entirely within the state of Pennsylvania. Its upper portions originate in the alternating ridge-and-valley formations of the Appalachian Mountains. While historically a prime source of sustenance in its fish and fresh water, the river, as it drew industry to its banks, found its natural benefits diminished by pollution and waste products. In the latter part of the twentieth century, new generations of environmentally conscious citizens acted to restore its natural qualities with multiple benefits for improved health and recreation for the three million people living within its watershed.

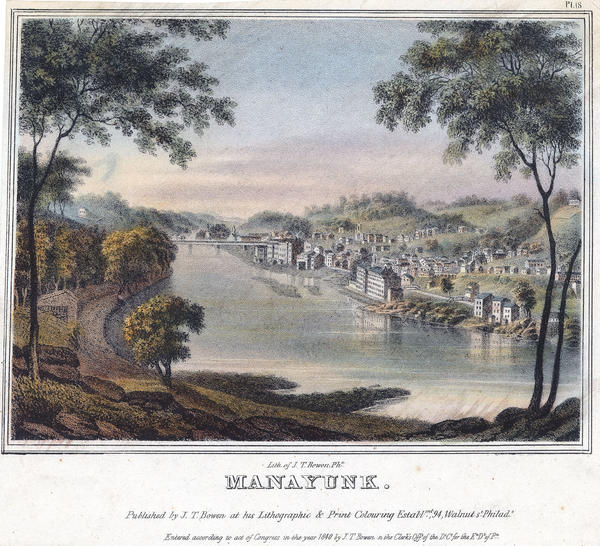

Native inhabitants had been camping and fishing on the banks of the Schuylkill for as much as fourteen thousand years before the first Europeans arrived in the seventeenth century. The area was first settled by the Unalachtigo subtribe of the Lenape or “original people” who settled in bands along the rivers and creeks of southeastern Pennsylvania. They referred to the river as Ganshowahanna, meaning “Falling Water” or Manayunk, which meant “where we drink.” A navigator, Arendt Corrsen (?-1645) of the Dutch West India Company, gave the river its modern name in 1628, when he became the first European to navigate it. Translated as “hidden river,” the name is thought to refer to the location of its mouth, obscured from the Delaware River by League Island, later the site of the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. In 1633, Corrsen was appointed commissary and instructed by the company to acquire land on the river for a plantation and trading post. He purchased a tract known as “Armenveruis” from the Lenape, and in the same year, the Dutch erected Fort Beversre[e]de on the site. This fortification stood until about 1651 near the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers near where the Platt Bridge was later erected.

Even as European settlement proliferated, the Lenape maintained settlements along the river, including Nittabakonck (“place which is easy to get to”), a village located where the Schuylkill meets the Delaware River. It was this area where William Penn (1644-1718) chose to lay out Philadelphia. Granted a charter to settle the area from Charles II (1630-85) of England as partial repayment of a debt, Penn nonetheless chose to buy the area from the Lenape to ensure peace for the colony. Selected with an eye to tapping the rich agricultural hinterland to assure the city’s growth, the site relied on its rivers for supplies of food and lumber that could be floated to the city when water was high enough—usually the spring.

Many streams flowed into the Schuylkill, including the Wissahickon, Plymouth, Sandy Run, Skippack, Pennypack, and Perkiomen Creeks, prompting the construction of dams and mills to produce grain, lumber, oil, paper, and powder and enhance trade. The presence of natural rapids, however, presented obstacles to boats. After several failed attempts in the 1780s and 1790s to fund improvements that would make the rapid-filled Schuylkill navigable, Philadelphia businessmen finally convinced the Pennsylvania legislature in 1815 to approve the charter of the Schuylkill Navigation Company to construct a slack water navigation system of canals, dams, and pools between Philadelphia and Pottsville to the northwest in Schuylkill County. Despite setbacks in funding and the death of the chief engineer, the system opened to navigation in 1824, and with an extension to Port Carbon four years later it generated the shipment of newly discovered riches of anthracite coal. Although supporters of the new system envisioned it primarily as a means of securing the flow of natural products to Philadelphia, especially grain (which local businessmen feared might otherwise be sent to Baltimore by way of the Susquehanna River), coal quickly dominated the business.

Industry Expands Along the River

By the 1840s, the transport of coal had shifted to rail, further enhancing development throughout the Schuylkill River valley. The shift could be seen in Reading, the county seat of Berks County. Boosted not just by the Schuylkill Canal but also the completion in 1828 of the east-west Union Canal connecting the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Rivers, the town of Reading continued to grow following incorporation of the Reading and Philadelphia Railroad in 1833. Farther south, Phoenixville, located at the junction of the Schuylkill and French Creek, utilized the Chester County Canal, completed in 1828, and the Reading Railroad to gain easier access to raw materials and more efficient transportation of finished products from iron works that had their origin at the onset of the nineteenth century. More generally, from 1820 to the 1860s iron works, foundries, manufacturing mills, blast furnaces, rolling mills, railroads, warehouses, and train stations sprang up throughout the Schuylkill Valley. Tiny farm villages grew into vibrant company towns, then transitioned into small cities as major industry and supporting businesses transformed local economics and populations swelled. By 1857 more than a million tons of freight moved each year through the valley’s diversified transportation system.

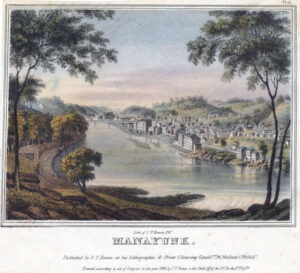

Within Philadelphia County industry concentrated along the river’s east bank. The effect of shifting energy regimes could be seen most notably in Manayunk—originally called Flat Rock Bridge—where by 1828 there were as many as ten textile mills powered by water backed up by a dam at the Schuylkill and directed through a two-mile canal constructed by the Schuylkill Navigation Company. The introduction of industrial capitalism undercut the dominance of flour milling as it had flourished for almost a century along the nearby Wissahickon Creek and prompted such popular designations of Manayunk as the “Lowell of Pennsylvania” and the “Manchester of America.”

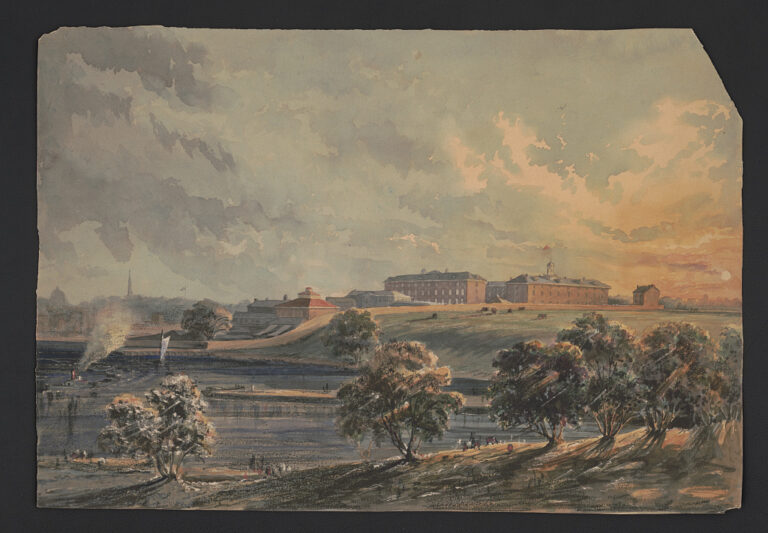

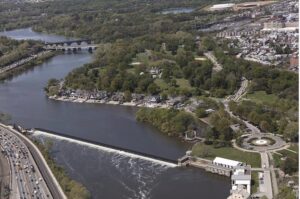

Even in the early years of Philadelphia’s commercial growth, officials grew concerned about assuring pure water for its residents. In 1799, the city established a watering committee and selected the Schuylkill as the city’s primary water source. As the city quickly outgrew a pumping station located in Centre Square at the heart of the old city, it directed city engineer Frederick Graff (1775-1847) to supervise construction of a water works at Fairmount, the prominent hill located on the Schuylkill’s east bank just north of the original city boundary. There engines would pump water from the river to a reservoir at the top of the hill, where it was distributed by a system of pipes to city subscribers. When steam engines proved costly and dangerous to operate, the watering committee converted the system to waterpower, assisted by construction of a dam at the Falls of the Schuylkill. Located where the river descends from the elevation of the Pennsylvania Piedmont to the low-lying Atlantic Coastal Plain, the area had long been the most famous natural attraction in the vicinity of Philadelphia. Not surprisingly, the area attracted the interest of Philadelphia’s wealthiest residents, who built country retreats free of the crowds, heat, and disease associated with the city. Construction of the dam at that location created a quiet pool upstream, ideal for rowing and skating. For the villas on the east bank of the river, however, the change brought swamp conditions and flooded meadowlands that reduced the attractiveness of country living. As conditions worsened, the city, in a further effort to protect the purity of the water, began buying up those estates, turning their properties into parkland. Boosted by state legislation in the 1860s, Philadelphia’ expansive Fairmount Park took form on both sides of the Schuylkill in the following years.

Dredging Near Girard Point

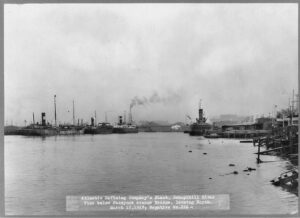

Most of the commercial traffic on the Schuylkill River plied the portion between Center City and its mouth because navigation farther north was impeded by the dam at the falls. Following the Civil War a series of wharves and docks went up on the river west of Center City to accommodate ships and barges transporting cargo including coal, ice, lumber, and stone. This increased commercial traffic prompted the United States Army Corps of Engineers to plan river improvements near the Schuylkill’s mouth. In 1875 and 1876 dredging took place in the channel near Girard Point, adjacent to what became known as the Penrose Ferry Bridge and near Gibson’s Point. This portion of the river was used to ship over 10.8 million bushels of grain to foreign ports.

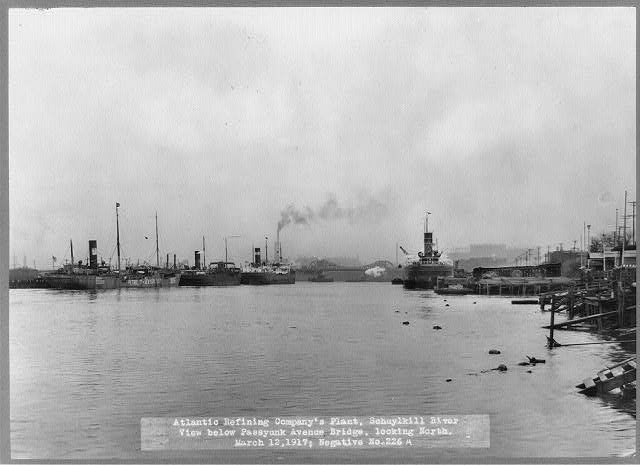

The Pennsylvania Railroad recognized the economic advantages of Philadelphia’s wharves for the import and export of grains including wheat, oats, and corn. Among the elevators constructed to sustain this trade, the largest was the International Navigation Company of Philadelphia’s 650,000-bushel Girard Point elevator erected in 1874 near the junction of the Schuylkill and the Delaware Rivers. Other industrial facilities taking advantage of a Schuylkill River location included the Atlantic Refining Company, established at the end of Passyunk Avenue in Point Breeze in 1860. It marked the advent of an influx of petroleum refineries into South Philadelphia. Initially established as a storage facility, by the 1880s it had become one of the largest refineries in the United States.

The transformation of land on both sides of the Schuylkill River from rural estates and farms to industrial and intensive-level residential use had direct consequences for the health of the river. As the Philadelphia region grew and its industries expanded, the Schuylkill’s pollution increased. The headwaters contributed the effluent from mine drainage and coal silt, and the lower sections were plagued with the waste of a large and growing population. According to the city engineer’s report for 1866, “Below Manayunk, the river assumes a dark, dirty, milky appearance, and is covered with soiled waste and shreds from shoddy mills … There is no doubt that a constant deterioration in quality is going on, which, if not arrested, will ultimately force the city to abandon the Schuylkill as a source of supply, if the time to do so has not already arrived.”

Problems worsened in the early twentieth century. As anthracite coal production peaked, large amounts of coal washing wastewater and coal silt discharged into nearby streams. To this were added sewer deposits described in a study by the Philadelphia Bureau of Engineers in 1913 as polluting the entire length through the city, to the point of preventing development along its banks either for pleasure or business. By 1927 the Army Corps of Engineers estimated that the Schuylkill River and its tributaries contained thirty-eight million tons of coal waste.

Clean Streams Act of 1937

Civic leader John Frederick Lewis (1860-1932) captured the sense of dismay shared by many residents in a 1924 illustrated address presented at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania published the same year. “Scores of cities with but a fraction of Philadelphia population, a tithe of her wealth, and a vastly larger per capita debt,” he charged, “might be cited as having recognized the wisdom of waterfront reclamation {and} sewage disposal by other means than by fouling their most valuable asset. Why should Philadelphia not do likewise?” The situation began to change when the Pennsylvania legislature unanimously passed the Clean Streams Act in 1937. A decade later Governor James H. Duff (1883-1969) directed a massive cleanup effort resulting in the excavation of twenty-three impounding basins along the river to receive dredged silt. In 1978 the Pennsylvania legislature responded to appeals from the Schuylkill River Greenway Association founded four years earlier, by designating the Schuylkill the state’s first Scenic River.

Restoration of the river accelerated at the turn of the twenty-first century. Building on the state’s designation of the Schuylkill as a Scenic River, advocates along the river corridor succeeded in 2000 in securing formation of the Schuylkill Greenways National Heritage Area and associated Greenways River Trail along the 128-mile corridor of the Schuylkill Valley with a commitment to repair environmental damage to the river and its surroundings. A 2003 report to the Schuylkill River Development Corporation on the state of the Schuylkill watershed brought together twenty-five nonprofit organizations with state and local agencies to pledge cooperation in addressing needs for clean water impacted by both population gains and losses along the Schuylkill’s tributaries. As a signature project, the organization launched Schuylkill Banks Park, a strip of parkland along the east bank of the river extending from the foot of Fairmount below the waterworks and south into the central city with an eventual destination of the Delaware River. Other organizations devoted to environmental stewardship of the river included the Delaware Riverkeepers Network, the Schuylkill River Greenway Association, the Schuylkill Highlands Conservation Landscape Initiative, the Middle Schuylkill River Conservation Landscape Initiative, the Lower Schuylkill River Conservation Landscape Initiative, the Schuylkill Action Network, the Phoenixville Iron Canal and Trails Association, and the Headwaters Association.

As much as was accomplished to boost the Schuylkill as a recreational asset, its industrial character, and the hazards it represented, were manifest in 2019 when a devastating explosion erupted at the former Atlantic Refinery site. While government and civic leaders sought to secure new environmentally safe uses for the property as the company entered bankruptcy, the costs of remediation and repurposing land under private ownership remained an obstacle, even as nearby residents struggled to secure compensation for damage to their health.

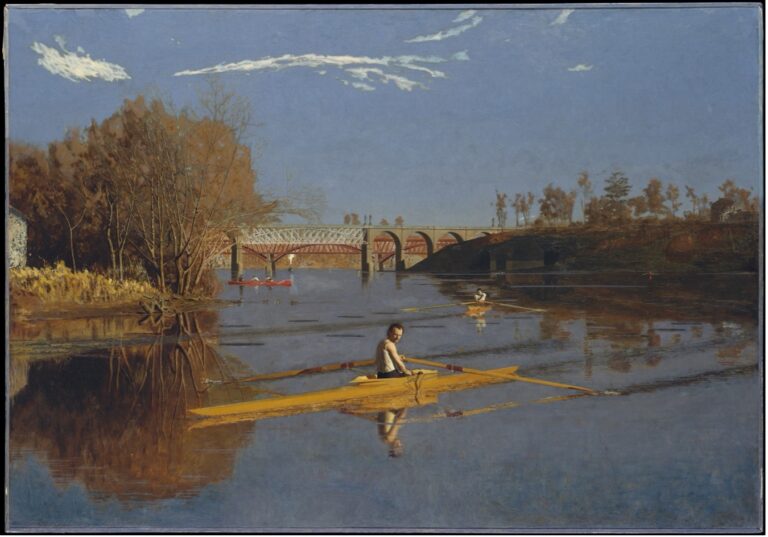

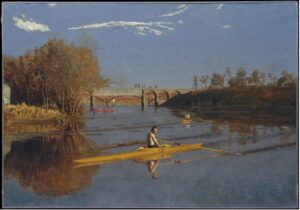

Over many years river area residents sought balance between beauty and production, serenity and empire. A longtime source of recreation, the Schuylkill’s mixed legacy was well captured by artist Thomas Eakins (1844-1916). A rower himself, Eakins captured the serene presence of rowers on the river never distant, however, from the emblems of industry located nearby. The modern effort to balance industry with nature was the reclamation of tidewater gardens at Southwest Philadelphia’s Schuylkill border. There, at the oldest surviving botanical garden in North America, Bartram’s Garden, founded in 1728 by botanist John Bartram (1699-1777), modern programs introduced area residents to the natural features of the river and the importance of their conservation. With industrial activity never far away from this spot, it served in the twenty-first century as a prime vantage point for encountering the river’s mixed heritage. Coincidentally the City Parks Association revisited John Frederick Lewis’s Redemption of the Lower Schuylkill with a similarly-named exhibit. Clearly, conservationists still had work to do. Yet even after centuries of development along the river’s banks, forests regrew to cover about 41 percent of the basin, representing important areas for recreation and wildlife. Agriculture still occupied 40 percent of the acreage while developed lands represented about 13 percent. Surface and groundwater resources in the basin continued to provide drinking water for more than three million people.

Howard Gillette is Professor Emeritus of History at Rutgers-Camden and Co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. This essay incorporates information gathered and compiled by Douglas McVarish, Principal, West Jersey Historical Research. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.