Botany

Essay

Beginning in the eighteenth century with the botanical enthusiasts who explored the world around them as part of a larger interest in natural history, botany became an integral part of the Philadelphia region’s national and international reputation. It brought scholars and enthusiasts from across the globe to study and explore Philadelphia’s collections and gardens, influenced the development of medicine and medical institutions, and cemented the intellectual reputation of Philadelphia as a place of scientific discovery. As individual efforts gave way to institutions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, organizations such as the Academy of Natural Sciences funded and publicized botanical expeditions and events, furthering Philadelphia’s botanical renown.

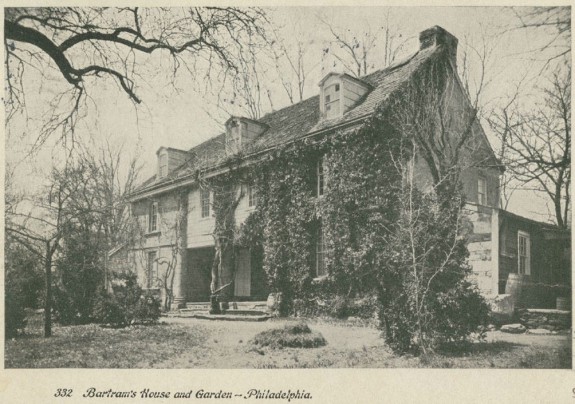

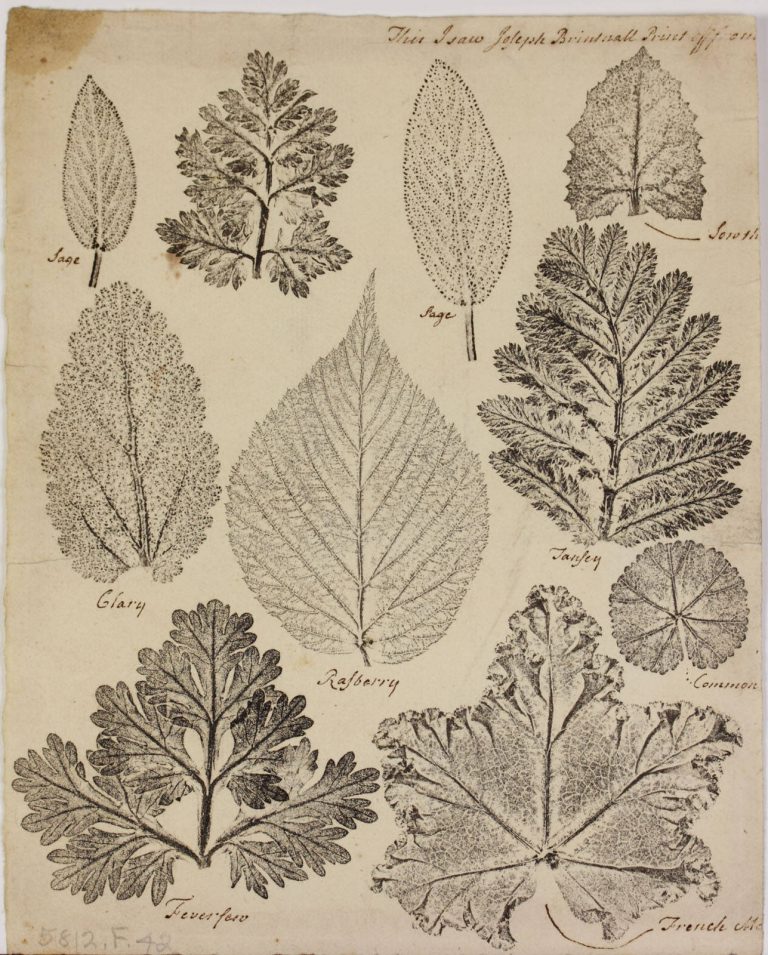

The Philadelphia region’s history as a botanical paradise and center of discovery began in the eighteenth century with the work of individual collectors and enthusiasts such as John Bartram (1699–1777), who used his home at Bartram’s Garden to cultivate and sell native plants to an international group of botanists and collectors, including Peter Collinson (1694–1768), Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), and Carl Linnaeus (1707–78). Linnaeus even named a variety of moss after Bartram in recognition of his botanical efforts. Bartram introduced as many as two hundred North American plant species into Europe, including the magnolia, mountain laurel, azalea, and rhododendron, and by the nineteenth century the botanic collection at Bartram’s Garden was the most extensive and varied collection of North American plants in the world.

Another eighteenth-century botanist operating in Philadelphia was Bartram’s neighbor, William Hamilton (1745–1813), who turned his country estate on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, The Woodlands, into a botanical paradise with a collection of native and exotic plants said to number ten thousand. The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden drew plant enthusiasts of all kinds to Philadelphia, from medical students studying botany and materia medica at the University of Pennsylvania to such international luminaries as André Michaux (1746–1802), Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), and Peter Kalm (1716–79).

Hamilton, John Bartram’s son William (1739–1823), and other area botanists ensured that later generations of botanists would continue to make their mark in the science by establishing Philadelphia as a training ground: Hamilton employed several gardeners who went on to international careers, such as nurseryman John Lyon (1765–1814) and botanist Frederick Pursh (1774–1820). Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), professor of botany and materia medica at the University of Pennsylvania, sent his student and protégé Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859) to both The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden for training.

Philadelphia continued to dominate the botanical scene in the nineteenth century. When, as president, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) sought to expand the sciences on a national level, he sent Meriwether Lewis (1774–1809) to study with Barton, Hamilton, and William Bartram before he headed west to explore the recently acquired lands of the Louisiana Purchase. As there was yet no national botanic garden or arboretum, both Jefferson and John Adams (1735–1826) saw Bartram’s Garden as the appropriate substitute.

Botanical practice underwent a number of changes in the nineteenth century, both in Philadelphia and farther afield. As the century wore on, reliance on individual botanists gave way to various new institutions focused around the promotion and propagation of scientific discovery. The American Philosophical Society begun by Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) had long been a promoter of enterprising individuals working to advance understanding of science, medicine, and literature, as had other, more narrowly focused Philadelphia institutions. The Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, the oldest agricultural society in the United States, had been sponsoring scientific farming experiments and developments since 1785 and included among its early members Benjamin Franklin, George Washington (1732–99), and George Logan (1753–1821), a politician and gentleman farmer whom Thomas Jefferson considered the best farmer in Pennsylvania. However, it was not until 1812, when the Academy of Natural Sciences was founded, that Philadelphia—and the entire Western Hemisphere—had an institution specifically and explicitly devoted to the study of the “natural sciences.”

The Academy of Natural Sciences promoted botanists and other scientists through the publication and dissemination of their work. It provided an alternative for young researchers who had plenty of ambition but lacked a wealthy elite patron or an independent income that would allow them to pursue botany as more than a hobby. The academy, which sponsored public lectures on botany for women beginning in 1814, popularized the discipline and made it accessible. It also funded increasingly ambitious collecting expeditions to the Arctic, Central America, Africa, and Asia. Other institutions soon followed, including the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, founded in 1827, which brought together botanical and horticultural enthusiasts; the Wagner Free Institute of Science, formally established in 1855, with the goal of bringing free science education to the wider public; and the Philadelphia Botanical Club (1891), which counted among its members several prominent naturalists such as Thomas Meehan (1826–1901) and John Harshberger (1869–1929). Institutional support of botanical and other scientific activities in Philadelphia contributed to the founding of the first college of pharmacy in North America in 1821, the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, which drew broadly on Philadelphia’s reputation as a center for botanical and medical science.

The later nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw even more expansion in botanical activities in Philadelphia and beyond as interest in new areas of study including conservation, evolutionary biology, and ecology grew along with a devotion to a more general public audience. In 1907 Pierre S. DuPont (1870–1954) established Longwood Gardens in Chester County as a botanical conservation and horticultural sanctuary outside the city, which grew into an extensive landscape devoted to public education in horticulture and ecological conservation. Other institutions furthered interest in botanical activities by capitalizing on the public’s interest in horticultural displays revived by the 1876 Centennial Exhibition and the construction of Horticultural Hall. A century later, the modern Horticultural Center in Fairmount Park replaced Horticultural Hall and brought visitors to the display and demonstration gardens all year round. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society built on this interest with its annual Philadelphia Flower Show (first established in 1829), which drew an estimated 250,000 visitors annually by the early twenty-first century, and its locally targeted efforts coordinated through the Philly Green program (established in 1974).

In the later twentieth century, institutional support for botanical activities expanded through consolidation as Philadelphia-area universities formed partnerships with other local institutions including the Morris Arboretum (University of Pennsylvania) and the Academy of Natural Sciences (Drexel University) to further ecological, horticultural, and biological research across multiple platforms. Botanical activities, consolidated under the larger umbrella of biology and life science departments and medical research programs, continued to expand our understanding of the natural world.

The story of botany in the Philadelphia region is a story of individuals and institutions that, from the eighteenth century forward, established Philadelphia as a city of botanical discovery and abundance as well as a destination for botanical enthusiasts from around the world.

Sarah Chesney is a historical archaeologist who earned her Ph.D. in anthropology from the College of William and Mary in 2014. She has worked on several landscape archaeology projects in Philadelphia exploring the intersection of archaeology, landscape, and early modern science. Her publications include “The Root of the Matter: Searching for William Hamilton’s Greenhouse at The Woodlands Estate, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” in Historical Archaeology of the Delaware Valley, 1600–1850, edited by Richard F. Veit and David G. Orr (University of Tennessee Press, 2014). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University