Centennial Exhibition (1876)

By Stephanie Grauman Wolf | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine, more simply known as “the Centennial,” opened in Fairmount Park to great fanfare on May 10, 1876, and closed with equal flourish six months later. Modeled after the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and the first in a long line of major “world’s fairs” in the United States, the Centennial exhibited national pride and belief in the importance of education and progress through industrial innovation. An additional mission of the Centennial grew from a desire to forgive and forget the Civil War.

Philadelphia had precedent for such a fair. The Great Central Fair of 1864, one of many held throughout the Union during the Civil War, anticipated the combination of public, private, and commercial efforts that were necessary for the Centennial. The Great Central Fair, held on Logan Square, had a similar gothic appearance, the waving flags, the huge central hall, the “curiosities” and relics, handmade and industrial exhibits, and even a visit from the President and his family.

The idea for presenting a World Exposition in Philadelphia honoring the hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence was first presented to Mayor Morton McMichael (1807-79) in 1866 by Professor John Campbell of Wabash College, Indiana. In 1871, with support from prominent businessmen such as John Wanamaker (1838-1922), the Republican political machine, and the Franklin Institute, the city and state successfully petitioned Congress to authorize the Centennial and set up a commission to oversee planning and implementation. The legislation explicitly excluded federal funding for the fair. The commissioners, led by Joseph R. Hawley from Connecticut as chairman and Alfred T. Goshorn from Ohio as director-general, were not political appointees but leaders in business. They were confident that the undertaking could be handled by private enterprise.

Although rich in historic associations, Philadelphia also presented problems as a site for the fair. Business sponsors and nonprofit organizations quarreled over whether to focus on commercial achievements or on American progress in the arts and sciences. Outside Pennsylvania, some suspected that the Centennial was merely an attempt to promote Philadelphia and its industries, and the nationally publicized kidnapping of 4-year-old Charley Ross from Germantown in 1874 painted the Philadelphia police force as corrupt and incompetent, raising fears for the safety of visitors.

Years of Fundraising

The Panic of 1873 dried up private financing. Fair organizers devoted the next several years to attracting attention and money from national, state, and foreign governments; from organizations like churches and universities; and from industrial and commercial associations. They enlisted newspapers all over the country in the cause. Members of the Women’s Centennial Committee had the most success raising funds, going from door-to-door in thirty-one states, selling stock and bringing in $100,000 in contributions. Still, with insufficient capital on hand as the opening neared, and the prestige of the United States at stake, the federal government was forced to step up. The government required repayment as first creditor, thus dooming the fair corporation to financial failure.

As a popular attraction, however, the Centennial was a great success. At a time when the population of the United States was 46 million, and that of Philadelphia less than one million, almost ten million paid admissions were recorded, with most people paying fifty cents to attend. While the majority of visitors were from Pennsylvania and its neighbors, 20,000 signed in from Illinois and more than 2,000 from California. On their special state days, Pennsylvania and New York each recorded over 250,000 attendees, while New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland listed over 10,000 each.

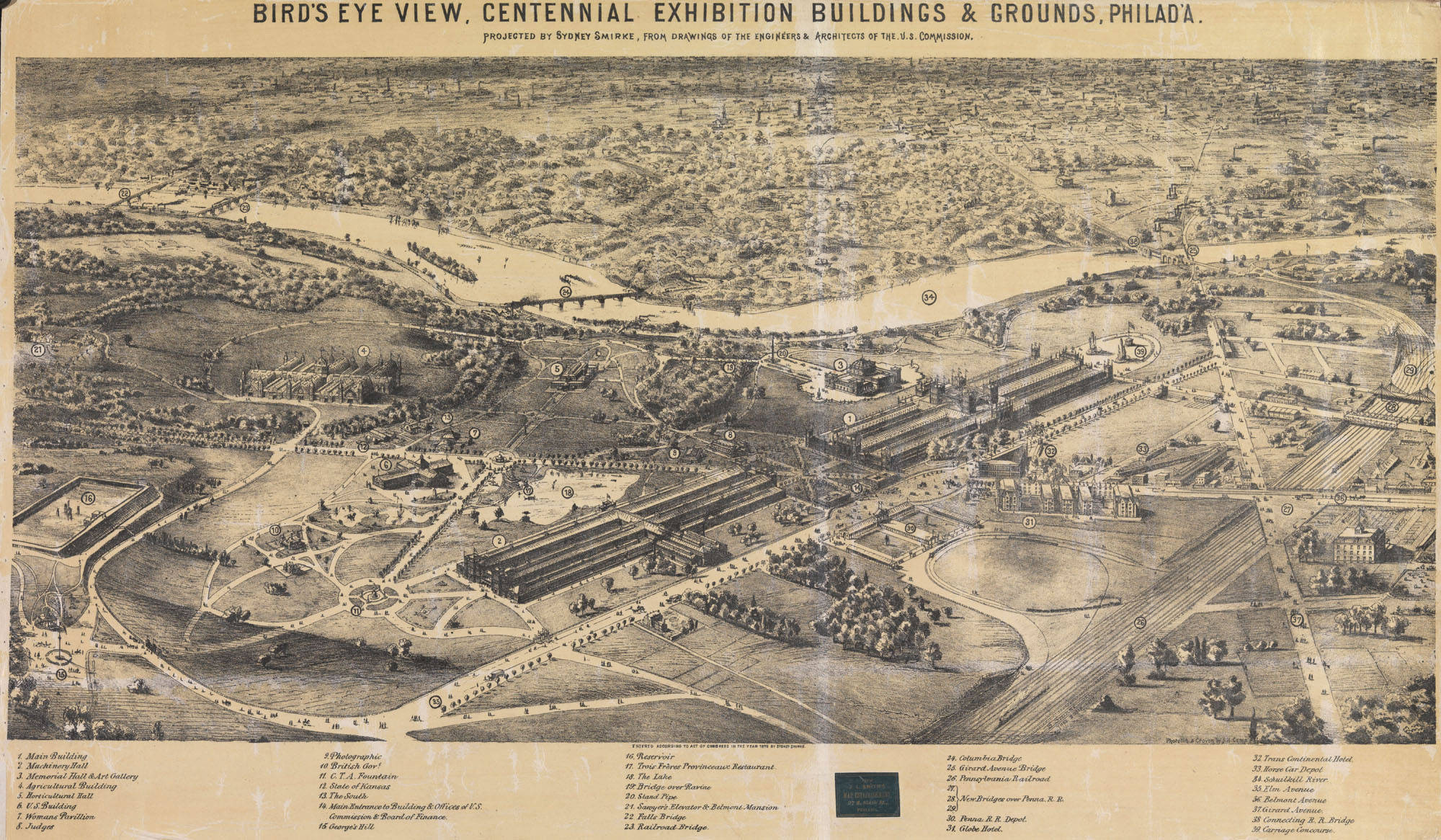

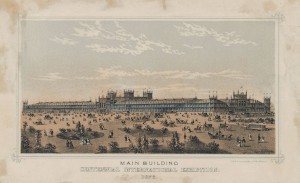

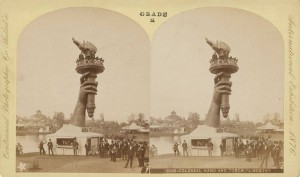

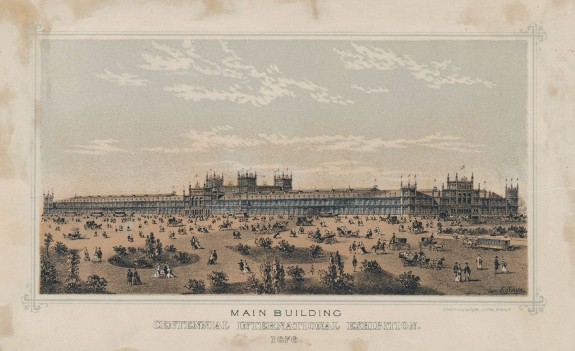

The Centennial overlooked the Schuylkill River, with 250 pavilions and seven miles of avenues and walkways occupying a 285-acre tract of Fairmount Park’s 3,160 acres. Many visitors arrived at the temporary “centennial station” of the Pennsylvania railroad and entered through the newly invented automatic turnstile. They found numerous fountains and statuary placed strategically throughout the grounds, prominent among them the arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty. Concessionaires, who paid up to 50 percent of their take for the privilege doing business within the fair, operated stands selling cigars, soda water, and popcorn, and theme-oriented restaurants, including French, Turkish, and Viennese.

42 Acres of Farm Exhibits

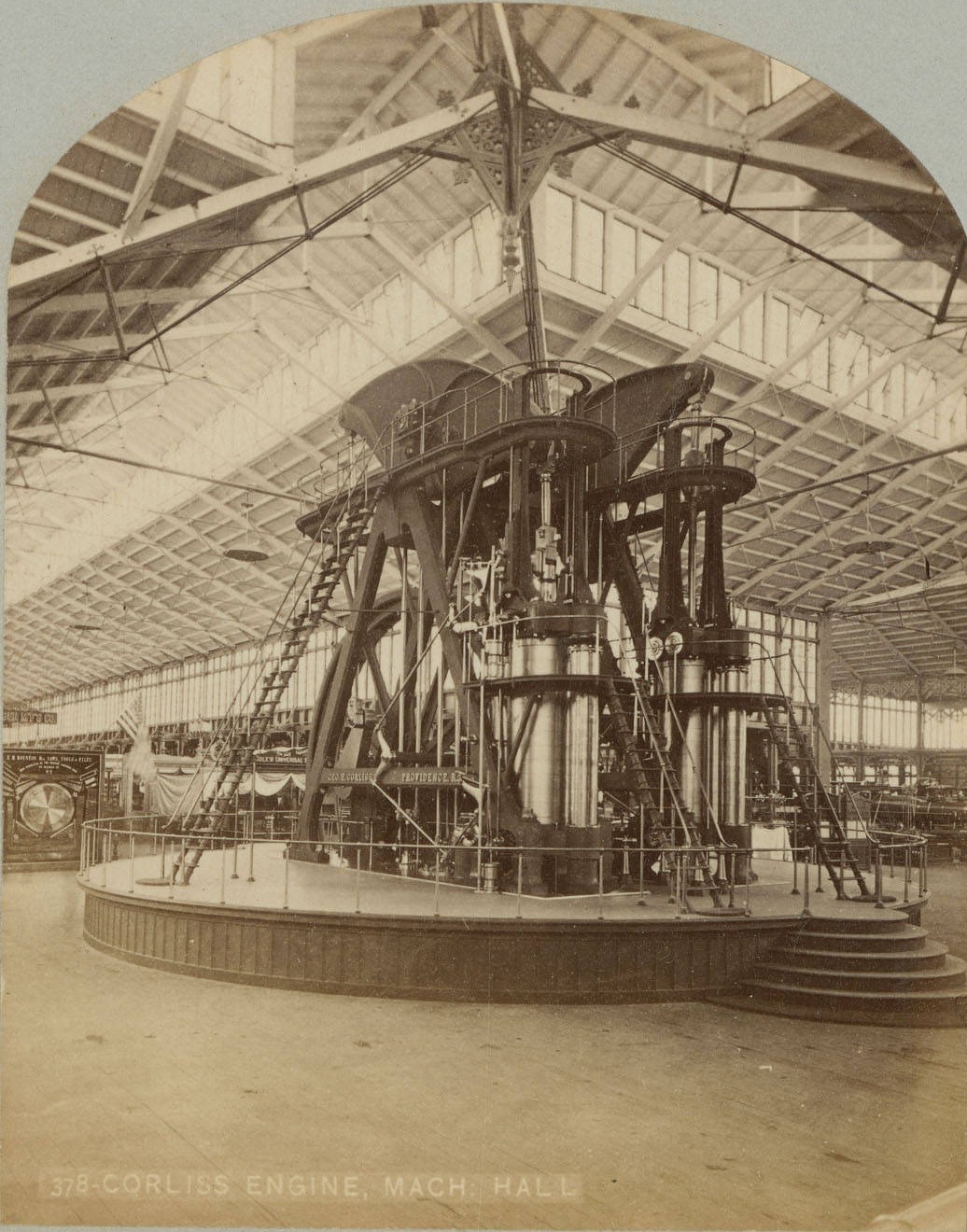

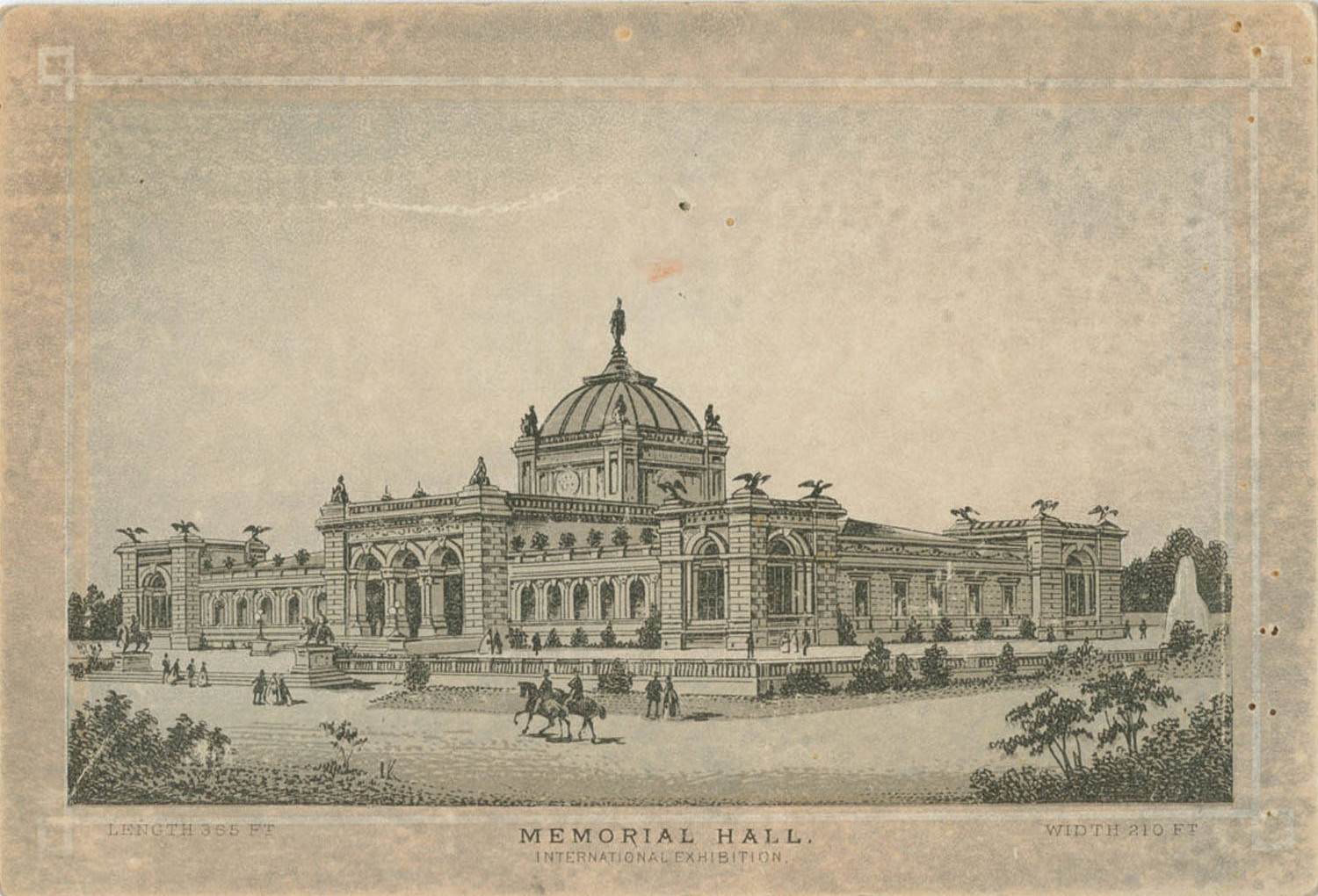

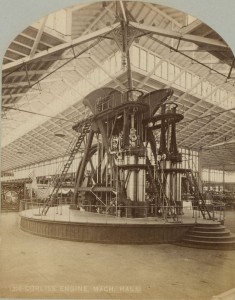

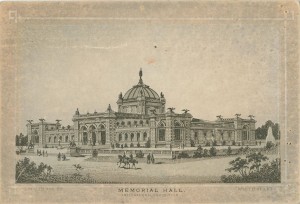

The Centennial Commission owned and managed thirty-four structures, including five central buildings that covered more than fifty acres. The largest, the Main Exhibition Hall, included exhibits on education and science but concentrated largely on the industrial arts and on selling merchandise. Machinery Hall housed the huge Corliss Engine, both the power source for the fair and perhaps its most popular attraction. Exhibitors demonstrated their processes of manufacturing while also offering their products for sale, increasing the interest of visitors. Agricultural Hall where the latest in farm equipment was demonstrated, along with forty-two acres of farm and livestock exhibits, was of particular significance for the still largely-agricultural nation. Horticultural Hall with its Victorian gardens and Memorial Hall with its exhibit of international fine arts were smallest of the main grouping. Other buildings run by the Commission included fire and police stations, a medical department, and seven “public comfort” stations.

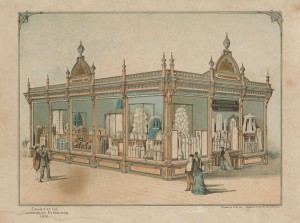

The remainder of the buildings, just over two hundred, represented several interests. The United States government contributed seven structures, including a main exhibit hall housing the Smithsonian collection, which later formed the nucleus of the Smithsonian Institution museum. Of the twenty-six states that erected buildings, most were either Pennsylvania’s neighbors or from the mid- or far West. Most of the South was still smarting from its loss of the Civil War and resented the request to spend money in the North which had caused so much loss and devastation to its own region. Only Mississippi participated from the deep South, frustrating the attempt of the Centennial Commission and the Federal government to present a picture of a country reunited. While thirty-eight foreign countries had a presence, only fifteen provided their own buildings. Forty buildings, the largest number, were either commercial enterprises like the Singer Sewing Machine Company or community service groups like the Bible Society.

The Commission advertised the main value of the Fair as educational, urging visitors to compare the contemporary strides in technology and learning with the state of the country one hundred years earlier, but the growth of a consumer society made shopping one of the most popular activities. The fair also offered frequent entertainment by musical groups from symphony orchestras to minstrel bands, special days sponsored by states and nearby businesses, and events like hot-air balloon ascensions and fireworks displays. Huge crowds turned out for the music, speeches, and celebrations that marked the opening and closing of the fair and the Fourth of July. “Curiosities” such as a full-sized Liberty Bell made of soap, “Liberty accompanying Washington” done in human hair, and a Centennial medallion carved in butter attracted attention.

Sideshows Arose Nearby

Outside the gates, a small, temporary city grew up along what later became Parkside Avenue. Flimsy, wooden structures housed dubious hotels, low-end restaurants, ice cream saloons, beer gardens, and “shows,” and were sandwiched two or three deep on narrow lots. They stretched a mile in each direction from the main gate and provided entertainment the Commissioners deemed inappropriate on the grounds proper. Profits trumped morality, however, and when attendance flagged at the fair, the organizers allowed the sale of wine and beer. However, they resisted opening on Sundays, and amusement-park rides and “hoochie koochie dancers” had to await the Chicago Fair of 1893.

Other values of the times were also on display, although not intentionally. Contempt and dislike of African Americans, laborers, and non-Anglo-Saxon foreigners often found expression in crude humor, such as exaggerated dialect, cartoons and stories found in books written about the Centennial. Victorian sensibilities demoted the graphic painting “The Gross Clinic” (1875) by Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) to the Army medical hall and banned all works by women from the Memorial Hall Art Exhibit.

A patronizing attitude toward women also pervaded the Centennial. Women responded with their own pavilion, built with funds completely raised by women, with all exhibits created and operated by them. Many labor-saving devices for domestic use, invented by women, formed part of the exhibit. While traditional forms of women’s work in needlework and china painting and achievements in the fine arts were not ignored, women also acted as engineers, wood workers, and printers, turning out newspapers and furniture and operating fabric-producing machinery. The chair of the Women’s Centennial Committee, Elizabeth Duane Gillespie (1821- 1901), a descendant of Benjamin Franklin, was seated on the platform for the fair’s closing ceremonies, but when rain curtailed the number of invited guests, admission was “refused to ladies’ tickets.”

Almost immediately after the Centennial closed, most physical remains were removed, either taken elsewhere or broken down and sold for parts. Much of the statuary and many of the fountains remained, as did the Ohio State building and two small, brick buildings used as “comfort stations.”

Two buildings were intended to be permanent, but Horticultural Hall was destroyed by a hurricane in 1954. Memorial Hall, ceased to be an art museum in 1928 and in subsequent years served as a gymnasium, swimming pool, and police station. In 2008 it was renovated and reopened as the Please Touch Museum, a children’s museum that includes a “Centennial Exploration” exhibit featuring a tabletop diorama of the fair on a scale of 1:192 feet. Commissioned in 1889 by John Baird, a former member of the Centennial Finance Committee, the model fulfills its intended mission of educating future generations about the Centennial Exhibition of 1876.

Stephanie Grauman Wolf is a senior fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies, University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- The Centennial Exhibition (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)

- The Centennial Exhibition (Digital Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia)

- After the Fair: The Development of Parkside (PhillyHistory.org)

- The Corliss Engine (PhillyHistory.org)

- Japan-a-Mania at the Centennial (PhillyHistory.org)

- Progress Made Visible: The Centennial Exhibition (University of Delaware Library)