Civil War Sanitary Fairs

Essay

Philadelphia’s Civil War sanitary fairs represented the spirit of patriotic volunteerism that pervaded the city during the Civil War. These grassroots efforts, climaxed by the Great Central Fair of 1864 in Logan Square, provided a creative and communal means for ordinary citizens to promote the welfare of Union soldiers and dedicate themselves to the survival of the nation. They also made Philadelphia a vital center in the Union war effort.

Sanitary fairs were civilian-organized bazaars and expositions dedicated to raising funds on behalf of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) and other charitable relief organizations. Over the course of the Civil War, they became one of the most popular means of fundraising for the Union cause. For Philadelphians, who had responded to the outbreak of Civil War in April 1861 with a surge of pro-Union patriotism, sanitary fairs provided a means of supporting soldiers and their families. While young men flocked to enlist, many of those not eligible for active duty because of gender, age, or other circumstances drew upon the traditions of antebellum benevolent societies to organize various soldiers’ relief agencies and to raise funds and collect food, clothing, bandages, and other supplies to be distributed to the troops.

The USSC was founded in the summer of 1861 when observers’ reports and soldiers’ uncensored letters to friends and family disclosed that many, if not most, federal recruits were subjected to decidedly unsanitary living conditions. While the mechanisms of infection were not understood in this pre-germ theory era, it became evident that a correlation existed between outbreaks of epidemic illness in the camps and the degree of filth and poor diets. As a flood of state-organized volunteer regiments swamped the administrative capacities of the Federal army, it also became evident that the U.S. government was poorly prepared to take care of its defenders. Thus some prominent citizens banded together to form the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which channeled volunteer contributions of money and materiel to improve living conditions and medical care for Union soldiers in the field and in the growing number of military hospitals.

Philadelphia Organization

Soon after the founding of the USSC, a cadre of local leading male citizens headed by Horace Binney Jr. (1809-70) formed the Philadelphia Branch of the USSC, which served as a regional executive center and depot to receive donated goods and monies. Women formed their own subsidiary, the Women’s Pennsylvania Branch of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which served as a conduit for receiving donations from hundreds of smaller, local aid societies.

Many of the local aid societies were subgroups of religious congregations and communities, such as the Ladies Aid Society of Philadelphia organized by members of the Tenth Presbyterian Church, the Hebrew Women’s Aid Society, the predominantly Quaker Penn Relief Association, and the Soldiers’ Relief Association of the Episcopal Church. Because African Americans generally were excluded from participating in USSC activities, Black congregations such as St. Thomas African Episcopal Church formed their own sanitary committees, which raised funds and channeled supplies to the U.S. Colored Troops and other Union soldiers.

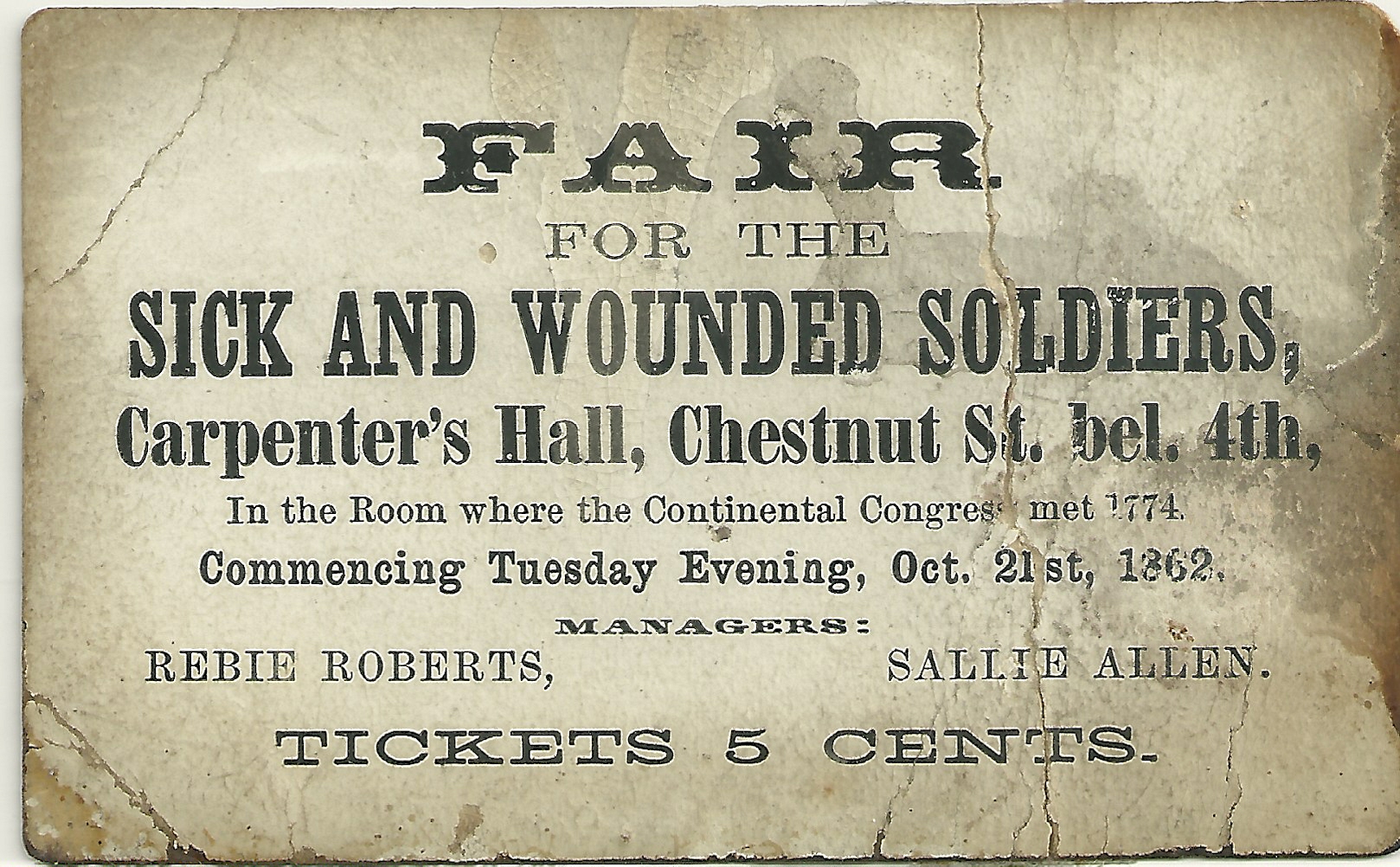

Whether local or national in scope, these organizations required vast, steady sources of funding to sustain their operations. In addition to soliciting donations from private citizens, merchants, and manufacturers, they staged fundraising events in Philadelphia throughout the war, including floral fairs, concerts, lectures, and plays.

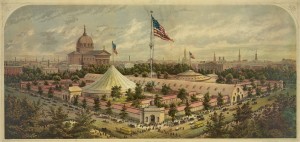

By far the largest and most successful of these events in Philadelphia was the Great Central Fair held at Logan Square (now Circle) from June 7 to June 28, 1864, to raise money for the Sanitary Commission. The fair was six months in the planning. Its Executive Committee, chaired by John Welsh (1805-1886), had oversight over myriad smaller committees in charge of soliciting contributions of goods, money, and services from members of every trade, profession, and commercial enterprise in the Philadelphia area. In final form the fair had close to a hundred departments and booths offering a broad range of appeal: Arms and Trophies, Children’s Clothing, Horse Shoe Machine, Fancy Articles (homemade), Turkish Divan for Smokers, Fine Arts, Brewers, Wax Fruit, Trimmings and Lingerie, Button-Riveter, Horticulture, Art Gallery, Umbrellas and Canes, Curiosities and Relics, and Steam Glass Blower. The Great Central Fair represented a successful amalgamation of the traditional ladies’ “fancy” and “floral fairs” and the more masculine industrial exhibitions that had become popular in the nineteenth century.

Spectacular Structures

The structures housing these wonders were no less spectacular than the contents. Built in just forty working days by volunteer craftsmen, the 200,000- square-foot complex featured Union Avenue, a 540-foot-long, flag-festooned central hall over which soared Gothic arches. The Avenue was flanked by rotundas to the south and north and other outbuildings, all interconnected by bustling exhibit corridors. Presiding over the entire Fair site was the Stars and Stripes, unfurled on a 216-foot flagpole.

President Abraham Lincoln, accompanied by wife Mary and son Todd, visited the Great Central Fair on June 16, 1864. Even though the cost of admission was doubled for that day, attendees mobbed the Fair to see the President. Lincoln contributed forty-eight signed copies of the Emancipation Proclamation, which were sold for $10 each. Ultimately, the Great Central Fair raised over a million dollars for the USSC through admissions, concessions, and the sales of goods and mementos. Of the many Northern cities that hosted major sanitary fairs between 1863 and 1865, Philadelphia was second only to New York City in money raised.

But Philadelphia was second to none in terms of patriotic pride and communal synergy, as demonstrated by its successful Civil War sanitary fairs and other volunteer efforts. These phenomena may still be viewed as representing Philadelphia at its finest.

Kerry L. Bryan holds a Master’s of Education from Chestnut Hill College and received training in historical research as a candidate for a Master of Liberal Arts degree at the University of Pennsylvania. As a historical consultant, she contributed to developing the “Philadelphia 1862: A City at War” exhibit at the Heritage Center at the Union League of Philadelphia. Her research focuses on benevolent agencies in Philadelphia during the nineteenth century, including the Civil War years. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University