Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

Essay

Historians have often situated Philadelphia in three geographic contexts: on the western edge of the “Atlantic World” during the colonial era, as an eastern metropole for hinterlands and the receding frontier to the west, and in the mid-Atlantic region between the North and South of the United States. These geographic frames all make sense, given Philadelphia’s location and history. But they do not tell the story of the more distant, but no less significant, connections between Philadelphia and the Pacific World—the lands in western North America and South America, Oceania, Australia, and Asia that circle the Pacific Ocean. Throughout the Pacific, primarily but far from exclusively with China, exchanges of industry, people, and ideas helped to make Philadelphia the city it became.

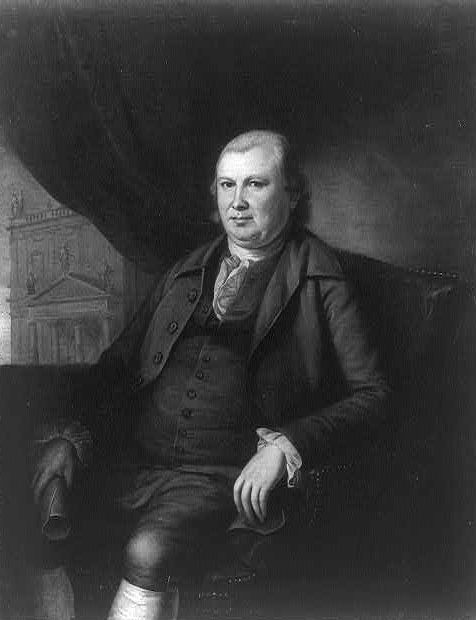

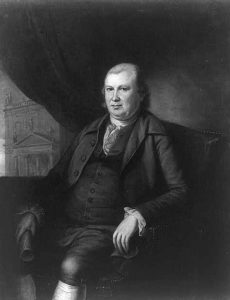

Philadelphians became active participants in trade with the Pacific after the American Revolution. With plentiful timber nearby and the expertise of settlers who had been shipbuilders in Great Britain, Philadelphia became a center for shipbuilding and a shipping industry that played a crucial role in connecting the city to the Pacific. In 1784, Robert Morris (1734-1806), the Philadelphia financier active in the Revolution, partnered with Daniel Parker of New York to launch the Empress of China, the first American ship to trade with Canton. Reflecting Philadelphia’s prominence in the shipping industry, John Green (1736-96) of Philadelphia was hired to captain the vessel. That same year the United States sailed from Philadelphia and became the first American ship to trade with India. By 1800, forty ships owned in and launched from Philadelphia engaged in the China trade.

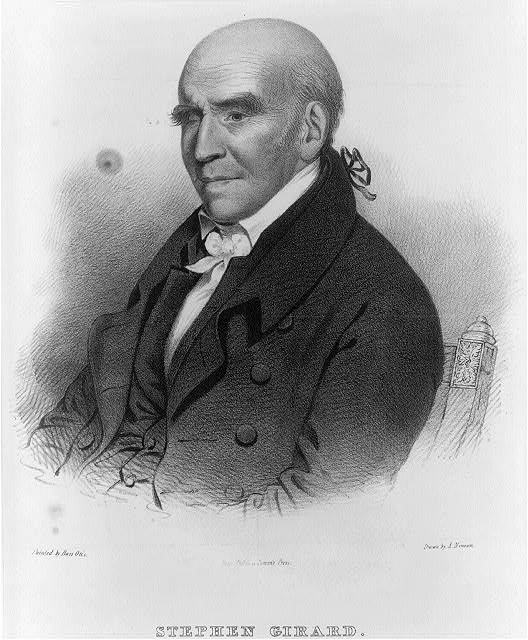

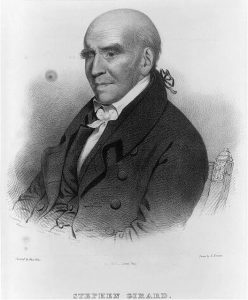

In the early nineteenth century, when the Napoleonic Wars cut Philadelphia off from its established trade routes and markets in the Caribbean, the city’s traders and merchants such as Stephen Girard (1750-1831) increased investment in commerce with China. These traders were instrumental not only to bringing Chinese goods to Philadelphia, but also to connecting dispersed parts of the Pacific region to each other. Because China offered little market for goods from the United States, Philadelphia merchants plied complex trade routes that moved furs from the Pacific Northwest of North America, hides from Chile, sandalwood from the Hawaiian Islands, and metals from the region later known as Indonesia into China. Return voyages brought silks, tea, and porcelain to the Philadelphia region and the nation.

Resources Fuel Commerce

Over the course of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia’s growth as an industrial and financial center and the Greater Philadelphia region’s natural resources helped to further connect the nation to the Pacific World and fueled commerce between the city and regions throughout the Pacific. Just as the shipyards had established commercial ties between Philadelphia and the Pacific, railroads extended this commerce. In 1837, Austrian artist Francis Martin Drexel (1792-1863), established in Philadelphia the banking house Drexel & Co. The bank provided a transcontinental financial link between Philadelphia and San Francisco during the California Gold Rush. Following the Civil War, Francis’s son Anthony Joseph Drexel (1826-1893) founded Drexel, Morgan & Co. (renamed J.P. Morgan & Co. in 1893), which was a major financier for U.S. railroad companies. The Baldwin Locomotive Works, established in 1835 at Broad and Spring Garden Streets, became the leading U.S. locomotive manufacturer by the 1880s, creating opportunities for commerce and transit between Atlantic and Pacific regions through the transcontinental railroad. Baldwin also exported its locomotives around the world, including to Australia, which experienced its own nineteenth-century transportation revolution through the spread of railways. Similarly, the Edge Moor Bridge Company, incorporated in Delaware in 1869 by Eli Garrett and the Philadelphia engineer William Sellers, exported iron and steel bridges to Australia and South America.

In 1897, University of Pennsylvania botanist William P. Wilson opened Philadelphia’s Commercial Museum as a center for information on international trade. Entrepreneurs from the Philadelphia region came to the museum to learn about foreign markets and goods. This coincided with the city’s rise as an industrial power and its adoption of the name “Workshop of the World.” Philadelphia’s industrial and manufacturing productivity joined the city to a global economy that included the Pacific both as a source for raw materials and as a market for finished products. This dominance, however, was short lived. By the 1920s, the U.S. Department of Commerce began providing much of the information that the Commercial Museum once did, and Philadelphia lagged behind other cities and ports in industry and trade.

While the Great Depression dramatically reduced Philadelphia’s industrial and economic output, World War II provided an opportunity for military production that buoyed Philadelphia but brought the city into violent contact with Japan. Philadelphia’s Navy Yard became a center for ship and aircraft construction; the Navy Yard also contributed to the development of atomic weapons, and the Frankford Arsenal produced arms and conducted munitions research. This military production ended along with World War II, but experienced a brief resurgence in the 1950 during the Korean War.

Notwithstanding the increase in war-related industrial activity, following World War II, Philadelphia’s industries suffered from increasing globalization and competition from industrial manufacturers in the Pacific region. The second half of the twentieth century was a period of general deindustrialization and economic contraction in Philadelphia. Improved shipping technology, standardization of production machinery, and increased use of synthetic fabrics helped Asian manufacturers to undercut Philadelphia’s many textile and clothing firms. Similarly, in the 1970s, the increase in imports of Japanese automobiles contributed to the decline of Ford, GM, and Chrysler factories in Greater Philadelphia.

Impact of Intellectual Curiosity

The pursuit of knowledge has spurred Philadelphians toward interest in the Pacific since the Revolutionary Era. The American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and John Bartram (1699-1777), was the first notable organization for the study of natural history in the city, but others followed, notably the American Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge in 1768, Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) and his Philadelphia Museum in 1786, and the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1812. These institutions made Philadelphia a center for scientific knowledge, publishing papers, housing collections, and promoting exploring expeditions of importance for the study and development of natural history in the United States. This pursuit of knowledge was a significant factor in the way many Americans living on the Atlantic coast learned about the Pacific World, a distant and exotic region that few would see for themselves. Several scientific projects connected Philadelphia to the Pacific. The American Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge emphasized in its manifesto that European plants did not thrive in North America and that the colonies should instead be considered more environmentally and agriculturally similar to China. The society noted that Philadelphia was at the same latitude as Beijing and that plants such as mulberry, persimmon, ginseng, and tobacco grew well in both North America and China. The group proposed introducing more plants from China to promote North American agriculture and economy. The Corps of Discovery Expedition, better known by the names of the expedition leaders, Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838), sought to connect Philadelphia and the Pacific geographically. American Philosophical Society member Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), who launched the expedition while president of the United States, held an abiding interest in the exploration of the North American continent and research into a continental route to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis, who studied at the University of Pennsylvania and consulted with several key figures in Philadelphia’s learned societies, organized much of his expedition from the city. Upon the expedition’s completion, Lewis and Clark gave many of the specimens they collected to the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Museum.

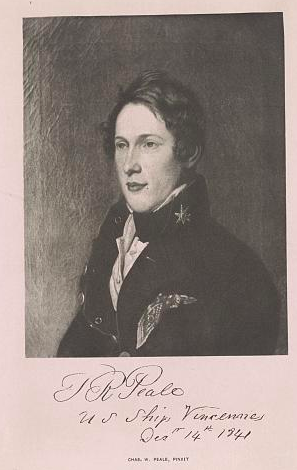

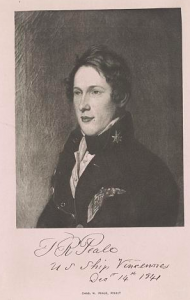

These institutions helped establish Philadelphia as a center for scientific knowledge and exploration of the Pacific World. Charles Willson Peale’s legacy extended to his children, who carried on their father’s interest in natural history to bring to Philadelphia greater knowledge of the Pacific. Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885), the sixteenth of Peale’s children, became a naturalist and explorer for several expeditions, most notably the 1838-42 U.S. Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Northwest, Oceania, and Australia. Titian Peale specialized in collecting animal specimens, bringing back 2,150 bird, 134 mammal, and 588 fish specimens. Other notable Philadelphia naturalists on the expedition included Charles Pickering (1805-78) from the Academy of Natural Sciences, and William Brackenridge (1810-93), a Scottish-born horticulturalist. The ornithologist John Cassin (1813-69), who became curator of the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1842, helped revise Titian Peale’s official report on the zoology he observed, helping to spread knowledge of distant species to American naturalists.

A Dutch Merchant’s Influence

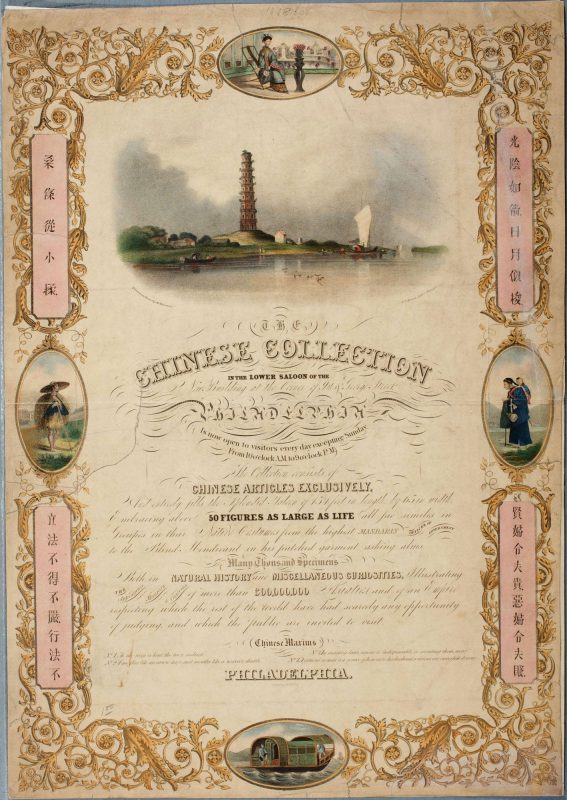

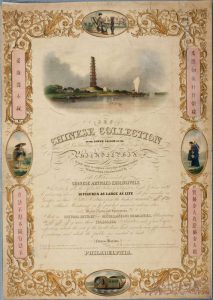

Others connected with the China trade also helped spread knowledge about this remote region and its cultures. The Dutch merchant Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest (1739-1801), who became a U.S. citizen in 1784 and thus claimed the record for the first American to visit China, introduced Philadelphians to a better understanding of Chinese material culture. When he settled in Philadelphia in 1796, Houckgeest built a country home called “China’s Retreat” that held mementos from his travels and was staffed by Chinese servants. Houckgeest also published an account of his visit to China’s emperor, further disseminating information about the nation to Americans. From 1818 to 1831, the merchant Nathan Dunn collected many Chinese artifacts and housed them in his summer home known as his “Chinese Cottage.” By 1838, Dunn chose to open a Chinese museum at Ninth and George (Sansom) Streets in Philadelphia, in the same space as the Peale Philadelphia Museum. Often known as the museum of “Ten Thousand Chinese Things,” Dunn’s collection educated and entertained the Philadelphia public. Dunn’s museum reflected great interest in Chinese culture: in its first year of operation, it attracted one hundred thousand visitors. This interest, however, or at least enough interest to be profitable, did not last long. By 1842, Dunn moved his collection to London.

Three decades later, the 1876 Centennial Exposition brought exhibits from Japan, China, Hawaii, and Australia, as well as the Latin American Pacific nations from Mexico to Chile. Out of the eleven nations that erected their own buildings for the exposition, only Japan represented the Pacific. This was, however, a significant step in educating Americans about the culture of Japan, which had been closed to the West until 1853. The Japanese exhibit included the first Japanese garden to be constructed in the United States. The site of the original Japanese exhibit, located in Fairmount Park, continued in the twenty-first century to feature a Japanese garden and host cultural activities.

Interest in art and artifacts from the Pacific found an outlet in Philadelphia’s cultural institutions. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, established from the art gallery of the Centennial Exhibition, collected Japanese and Chinese art, including ceramics, metalwork, and textiles, which were displayed in prominent exhibits in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Founded in 1887, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (more familiarly known as the Penn Museum) demonstrated strong interest in collecting ethnographic artifacts and material culture objects from Oceania, insular Southeast Asia, and Australia. The Penn Museum sponsored several expeditions to the Pacific and also purchased items from international dealers, housing them in a permanent Oceanian section of the museum.

Artifacts and Controversy

The practice of collecting artifacts and specimens sometimes led to controversy over the appropriation or theft of important cultural objects. In 1924, the Penn Museum purchased a large collection of ceremonial items from a Tlingit clan from coastal Alaska. In the early twenty-first century, Tlingit groups sought the return of these items, but met with resistance from the museum. In 2016, the federal repatriation review committee, under the auspices of the Native Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, determined the items must be returned to Alaska.

In addition to the collection of artifacts, literary arts connected the Philadelphia area to the Pacific world. Through their work, Philadelphia-area authors introduced Americans to life and culture in the Pacific. Pearl S. Buck (1892-1973) settled in Bucks County after spending the first forty years of her life in China. Buck’s experiences with peasant life in China led her to publish The Good Earth (1931), which won the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for the novel. Buck published several other works of fiction about life in Asia and translations of Chinese fiction, including East Wind: West Wind (1930), Sons (1933), All Men Are Brothers (1933), A House Divided (1935), and The Big Wave (1948). Doylestown native James A. Michener (1907-97), provided many Americans with a compelling, though often romanticized, view of Polynesia and Alaska through his prolific writing. Michener, who was stationed in the South Pacific Ocean as a naval historian during World War II, used his observations to write Tales of the South Pacific (1947), which won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and was adapted by Rodgers and Hammerstein into the Broadway musical South Pacific (1949). Michener later published many other short stories and novels about the Pacific World, including Return to Paradise (1950) about the South Pacific, The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1953) about wartime Korea, Sayonara (1954) about cultural conflict in post-war Japan, and Hawaii (1959) and Alaska (1988), two epic novels about both places’ long histories and experiences with U.S. colonialism. Buck and Michener both went on to become philanthropists and activists after achieving fame through their writing. Buck promoted cross-cultural understanding and humanitarianism through the Welcome House Adoption Agency (1949) and Pearl S. Buck International (1964), and Michener helped found the James A. Michener Art Museum (1988), all located in Bucks County.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Philadelphia remained a center for the study of Euro-American and European exploration in the Pacific and its history. In 1969, the Academy of Natural Sciences led a team to search Australia’s Great Barrier Reef for artifacts discarded from Captain James Cook’s HMS Endeavour when, in 1770, the ship struck a reef and nearly sank. One of the Endeavour’s ten-pound cannons became part of the academy’s collections. The Endeavour cannon, recovered from a shipwreck that occurred as Philadelphia was beginning to take interest in the Pacific, can serve as a reminder of the complex networks of economic and cultural exchange that have tied the city to a distant ocean. University-based programs focused on areas of the Pacific also proliferated throughout Greater Philadelphia’s institutions of higher education. Princeton University became a leading center for East Asian studies, and its East Asian Library and Gest Collection assembled a large body of rare books and archival material from China, Japan, and Korea.

Immigrants from the Pacific

Philadelphia’s population of immigrants from Pacific nations was small but significant. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Philadelphia’s rate of immigration from foreign countries was lower than that of many other U.S. cities, and most of the city’s immigrants came from Europe. Nevertheless, communities from the Pacific World, particularly China, did much to shape Philadelphia’s modern history. Philadelphia became home to a growing population from the Pacific World in the late nineteenth century. In the 1870s, in the face of anti-Asian hostility, Chinese migrants made their way east from the railroads and gold mines of the North American West. The migrants first settled around Ninth and Race Streets, near what was then Philadelphia’s Skid Row.

This small community established Philadelphia’s Chinatown. At first, Chinese residents of the city were restricted to working in domestic service, laundries, or small groceries; small eateries and community associations served as places for cultural and social cohesion. By the turn of the twentieth century, the neighborhood’s “chop suey joints” gained notice from non-Asian Philadelphians. Flavors of the Pacific expanded the already diverse food culture, which had been shaped since colonial times by the city’s shipping industry and cosmopolitan upper class.

The Asian and Pacific Islander population of the city remained below two thousand during the first half of the twentieth century, after the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted new immigration. During World War II, the Greater Philadelphia region experienced an increase in its Asian population through the relocation of Japanese Americans from federal concentration camps. Seabrook Farms, located in southern New Jersey’s Cumberland County, was a major supplier of vegetables to the U.S. military and a beneficiary of Japanese American workers employed through a program of the War Relocation Authority. Between 1944 and 1946, 2,700 Japanese Americans came to work at Seabrook. Following World War II, new immigration contributed to a significantly larger and more diverse Pacific population. Cultural institutions such as the Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church at Tenth and Vine Streets served not only as a religious center but also as an organizing point for Chinese involvement in city politics as Chinatown residents worked to protect their interests.

Meanwhile, armed conflicts in the Pacific region had significance for Philadelphia and its population. Philadelphians in the military who deployed to the Pacific returned home with greater knowledge of the region, while anti-war activists sought to bridge cultural differences to mount resistance to the war in Korea and, later, Vietnam. In the aftermath of the Vietnam conflict, Southeast Asian refugees began settling in Philadelphia. Often placed in areas already suffering from racial and economic conflict, they frequently became targets of violence. However, Vietnamese and Cambodian communities persisted and grew; Philadelphia became home to some of the largest Vietnamese and Cambodian populations on the East Coast.

The Philadelphia region’s many universities fostered not only education about the Pacific but also the exchange of people between the two regions. In 1982, Temple University became the first American university to establish a campus in Japan. In the early twenty-first century, the universities of the Philadelphia area attracted a large number of students from the Pacific region, with the majority of foreign students originating from China.

While Philadelphia’s geographic position places it firmly in the Atlantic World and on the United States’ Eastern Seaboard, intercourse with the Pacific has nonetheless been a significant factor in the history of the Philadelphia region. Connections to Pacific people and places have helped Philadelphia develop commerce and industry, grow into a center for the exchange of knowledge and ideas, and become home to a diverse and multicultural population.

Lawrence Kessler holds a Ph.D. in history from Temple University and is a postdoctoral fellow at the Consortium for History of Science, Technology and Medicine.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware forges agreement with China to pursue new investments (WHYY, January 20, 2011)

- From your driveway to China (WHYY, March 3, 2011)

- Memorial service pays special honor to one Korean War soldier from Fishtown (WHYY, May 25, 2015)

- On eve of Pacific Rim trade vote, area legislators wary of another NAFTA (WHYY, June 12, 2015)

- Chester County delegates to China led to deals for mushrooms, beer (WHYY, May 15, 2017)

Links

- Dusting The Sand Off Of Philly’s Tiki Heritage (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- China Trade (Independence Seaport Museum)

- Philadelphians and the China Trade, 1784-1844 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- Chinatown at a Glance (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Ginkgo Tree of Chestnutwold (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Japan-a-mania at the Centennial (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Barroom Brawl That Changed Chinatown (Hidden City Philadelphia)