Fairmount Park

Essay

Fairmount Park was developed in the nineteenth century in an effort to protect Philadelphia’s public water supply and to preserve extensive green spaces within a rapidly industrializing cityscape. It became one of the largest urban riparian parks in the United States and comprises the largest contiguous components of Philadelphia’s public park system as administered by Philadelphia Parks & Recreation Department (PPR): East and West Parks on the Schuylkill and the surface of the Schuylkill River within those parks. From 1867 to 2010, when park management was overseen by the Fairmount Park Commission, the Wissahickon Valley Park (2,042 acres) was also considered part of Fairmount Park.

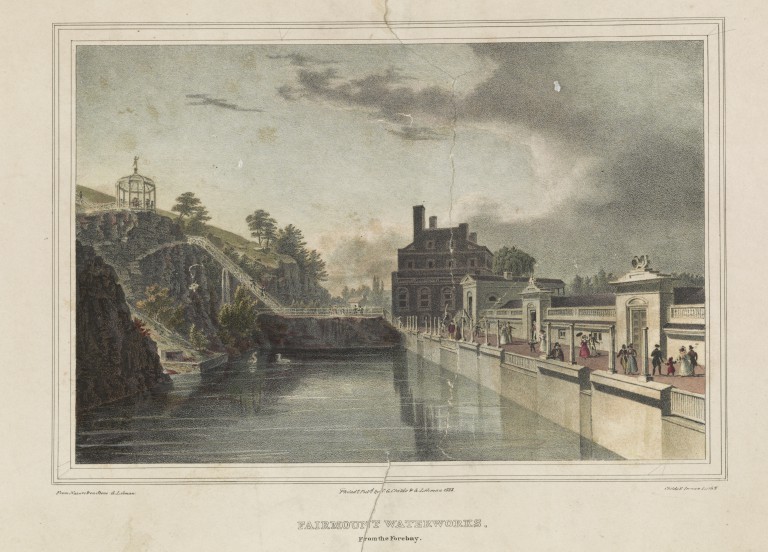

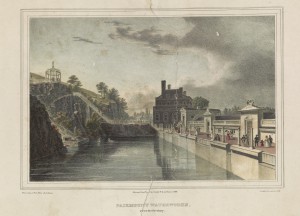

Among noteworthy cultural institutions within Fairmount Park are the Philadelphia Zoo, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Please Touch Museum, the Horticulture Center, and the Shofuso Japanese House and Garden as well as historic houses and industrial sites such as Mount Pleasant, Woodford, and Strawberry Mansion, and the Fairmount Waterworks. Boathouse Row, on the east bank of the Schuylkill, is an international center for competitive rowing.

Origins

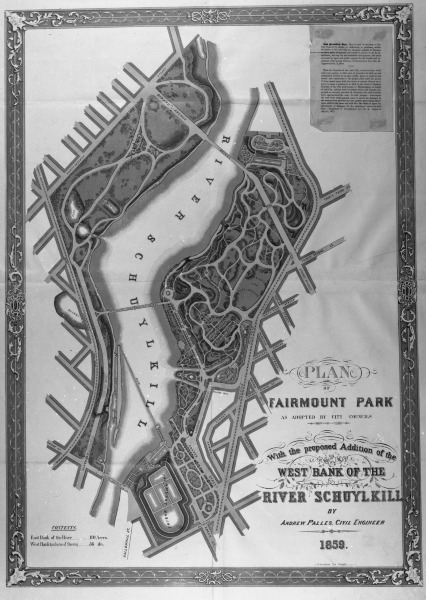

“Fairmount” is the prominent hill located on the east bank of the Schuylkill River just north of the original boundary of Philadelphia. It was named by William Penn (1644-1718) when he claimed it as part of his Springettsbury manor. During the eighteenth century, the Schuylkill district was celebrated for the rural estates and elegant villas that lined the river banks west of the evolving city. In 1812, Philadelphia City Council’s watering committee purchased Fairmount for a new waterworks facility. Development of the park began in the 1820s, when gardens and walkways were laid out around the waterworks. The park was expanded in 1844, when the city purchased the nearby Lemon Hill estate. The 1854 Consolidation Act directed the development of public parks, and in 1855 Lemon Hill was dedicated as “Fairmount Park.” In 1857, the city acquired the adjoining Sedgeley tract. A year later, James C. Sidney (ca. 1819-81) and Andrew Adams (ca. 1800-60) were hired to relandscape the conjoined estates. Some new roads and plantings were completed, but the project was suspended in the mid-1860s, when park advocates successfully lobbied the state to authorize the development of a much larger park on both sides of the river.

Acts of Assembly in 1867 and 1868 created the Fairmount Park Commission (FPC) with authority to expropriate properties along the Schuylkill and the Wissahickon for recreation and to protect the city’s water supply. Although commission members consulted landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and Calvert Vaux (1824-95) about viable strategies for reconfiguring the park landscapes, the FPC decided to make minimal changes so as to protect the “scenic contours” of the historic river estates. This plan was also cheaper. The FPC relied on appropriations from the city, and while funds were made available to compensate landowners whose properties were expropriated, the city resisted financing comprehensive landscape improvements.

Expansion

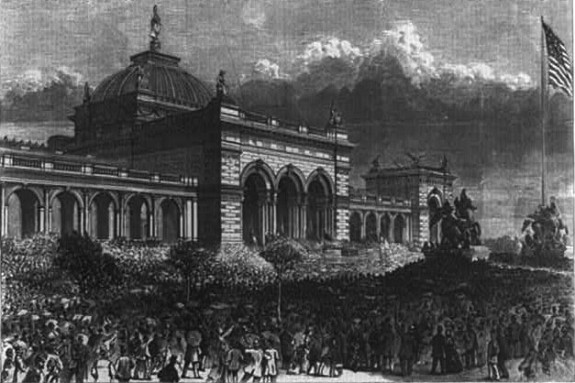

The rapid acquisition of properties enabled Philadelphia to host the 1876 Centennial Exhibition on a four-hundred-acre exhibition site in West Park. Funding from city, state, and federal governments as well as private sources enabled the FPC to open roads and build drainage systems within the park as well as to build two new cultural facilities: the Horticulture Hall conservatory and Memorial Hall, which subsequently housed the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art.

By 1900, the Schuylkill and Wissahickon park areas encompassed some three thousand acres, and Philadelphians boasted of having created the country’s largest urban park. During the twentieth century, more land was added to East and West Parks and the Wissahickon until the three areas comprised roughly 4,500 acres. By acquiring so much acreage so quickly, the FPC assembled disparate landscape spaces that ranged from well-tended gardens to broad greenswards and forests. Some cohesion was provided by the Schuylkill and Wissahickon waterways that bisected these spaces, but the lack of a comprehensive plan for landscaping improvements or management produced some unique features. For example, preexisting railroads and major streets were allowed to remain within the park; at a later date parkways and streetcar lines were added to improve access. Fairmount Park’s boundaries varied from the hard edges of city streets to permeable dells along the Wissahickon. The presence of railroads and other thoroughfares left the park areas vulnerable to additional intrusions, most notably I-76, the Schuylkill Expressway, which was cut through the West Park in the 1950s.

Recreation

The creation of Fairmount Park did not introduce recreational areas into Philadelphia’s urban landscape because both the Schuylkill and the Wissahickon had been popular recreational destinations since the eighteenth century. Many property owners at the Schuylkill and Wissahickon permitted public access to their lands: in the early nineteenth century Henry Pratt admitted the public to his extensive gardens at Lemon Hill. In the late 1850s, newspapers reported hundreds of residents, “white, yellow, brown and Black,” assembled for civic festivals in the newly dedicated Fairmount Park. After 1867, both organized sports and more informal forms of recreation continued throughout park areas. Spectators flocked to the Schuylkill to watch competitive rowing races until baseball supplanted this as a spectator sport. Cyclists first entered the park in the 1880s. Equitation was always popular. During the twentieth century, the FPC added more formal recreational facilities such as ball fields and basketball and tennis courts, as well as entertainment venues, including the Lemon Hill band shell, the Robin Hood Dell, and the Mann Music Center.

By the mid-twentieth century, when city government and the FPC had established numerous parks in other areas of the city, the Schuylkill and Wissahickon parks were considered the nucleus of what became known as the “Fairmount Park System,” encompassing some ten thousand acres citywide. Following the disestablishment of the FPC in 2010, the term “Fairmount Park system” was retired, the Wissahickon was designated as an independent entity, and “Fairmount Park” was redefined to describe only East and West Parks along the Schuylkill.

Elizabeth Milroy is Professor and Department Head of Art & Art History at the Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, Drexel University. She is the author of The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places, 1682-1876 (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- What's Your Vision for Fairmount Park? (WHYY, September 24, 2013)

- Fairmount Park Plans for the Future (WHYY, May 4, 2015)

- Fairmount Park Conservancy launches new guide for enjoying Fairmount Park (WHYY, August 15, 2016)

- Centennial Commons carves out space for East Parkside neighbors to connect (WHYY, June 13, 2018)