United Nations World Capital

Essay

In 1945 and 1946, Philadelphians campaigned aggressively to persuade the United Nations to place its new permanent headquarters in Philadelphia. As they chased the honor of becoming the “capital of the world,” however, they discovered that the city’s historic associations with the American Revolution did not impress the world’s diplomats at the end of World War II. The campaign succeeded in making Philadelphia one of three finalists for the headquarters site, but it ultimately failed in the face of John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s (1874-1960) offer to spend $8.5 million for a midtown Manhattan location.

The campaign to attract the United Nations to Philadelphia began in March 1945 with J. David Stern (1886-1971), publisher of the Philadelphia Record newspaper. Stern, a Philadelphia native then living in Haddonfield, New Jersey, published a front page editorial headlined “Philadelphia—Home of the United Nations” next to a photograph of Independence Hall. In the editorial and in a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), Stern argued for placing buildings for the United Nations around Independence Hall to inspire diplomats with the American example of political liberty and democracy.

As UN Took Shape, Philadelphia Leaped

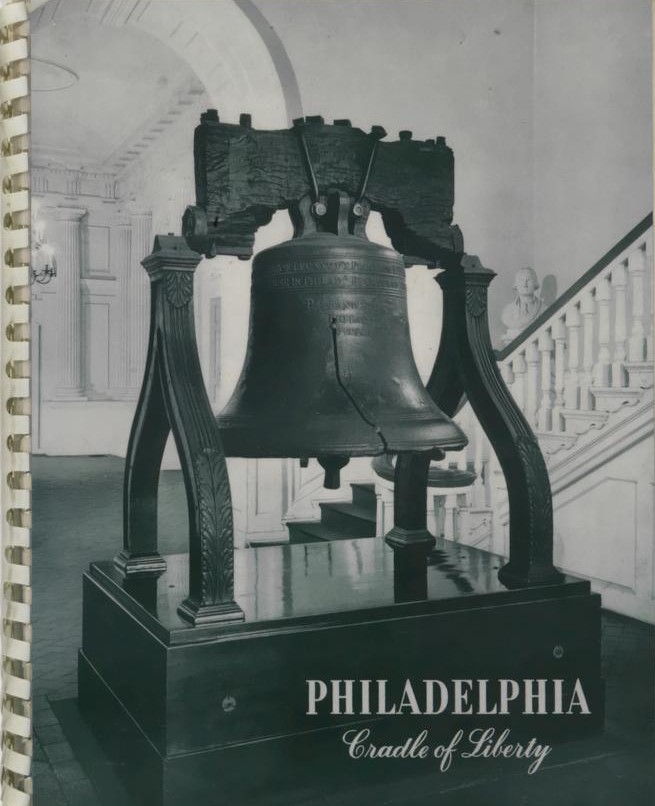

The United Nations had not yet formally organized when Stern advanced his idea for bringing the world organization to Philadelphia. That occurred later, during a conference in San Francisco in May 1945 and a UN Preparatory Commission meeting that autumn in London. But Philadelphia government and business leaders leaped energetically to pursue the prize, encouraged by daily coverage in Stern’s newspaper. Without invitation, determined to win the honor, they sent emissaries to San Francisco and London and produced an elaborate booklet with the Liberty Bell on the cover and photographs of historic and scenic Philadelphia. They sold themselves as the best possible setting despite Philadelphia’s lack of international commercial air service at that time. To get to London, the city’s promoters had to first take a train to New York.

Philadelphia’s promoters quickly discovered that the idea of becoming the “capital of the world” had ignited the imaginations of boosters from other American cities and towns. A competition began among a few early contenders and escalated to at least eighty before the UN’s diplomats even began to consider the question of a headquarters site. The hopefuls included other major cities such as Boston, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, as well as seemingly remote places like Claremore, Oklahoma; Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan; and the Black Hills of South Dakota. Ultimately, more than one hundred American cities and towns (but few from other countries) angled for the diplomats’ attention. Philadelphia’s interest did not stop competition from the nearby region, including Valley Forge, Easton, the Poconos, and Atlantic City. At the end of World War II, which had connected every local community with global conflict, and at the dawn of widespread commercial aviation, any spot in the United States could imagine itself as the center of the world.

Philadelphia and other American communities extolled local and national attributes, but the UN diplomats who set criteria for a headquarters site at the end of 1945 had other needs in mind: good worldwide communications and favorable public opinion toward the new world organization. The UN needed a hall to accommodate six hundred delegates, plus committee rooms and accommodations for the press and support staff. Imagining a headquarters compound with its own identity, the diplomats initially ruled out cities and looked for sites of forty-two acres or more in suburban areas surrounding New York or Boston. The specified radius around New York excluded Philadelphia but still incorporated Atlantic City, which for a time became an option as a temporary meeting place because of its hotels and convention facilities.

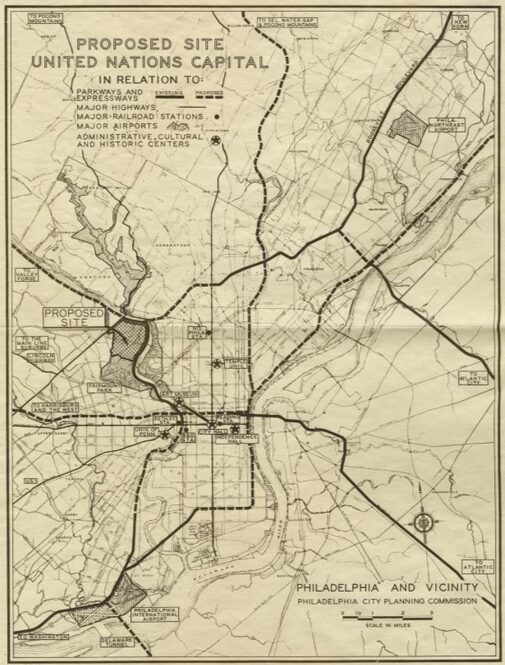

The City Offers Belmont Plateau

Stung by their exclusion, Philadelphians pivoted to a new strategy that emphasized the modern facilities sought by the UN or, if they did not exist, the capacity to create them. Setting aside the earlier vision of a UN complex around Independence Hall, they offered Belmont Plateau in Fairmount Park as a suitably pastoral setting with potential housing sites for staff in Roxborough and Chestnut Hill. They lobbied persistently in 1946 as the United Nations gathered for its first official sessions in temporary quarters at the site of the World’s Fair of 1939 in Flushing Meadows, New York.

Philadelphia’s hopes to become the United Nations world capital sprang anew when the diplomats encountered resistance from residents near the suburban site they most favored, north of New York City near Greenwich, Connecticut. A new round of consideration opened, and this time Philadelphia merited a site visit in a narrowed competition with San Francisco and New York. In the end, however, the fortunes of the Rockefeller family settled the matter. John D. Rockefeller Jr. provided the funds, and his son Nelson (1908-79) brokered the deal to place the UN on a site that New Yorker boosters favored, in midtown Manhattan facing the East River. Despite all previous plans and aspirations, the United Nations would occupy an office complex, not a freestanding capital of the world.

In the publicity campaign they constructed to attract the United Nations, Philadelphians at the end of World War II revealed how they perceived their city and its place in the world. Their campaign initially celebrated the symbolic significance of Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, which they assumed to be indisputable inspirations for the world. Philadelphia’s promoters learned that in the postwar era, the symbols they treasured were less important than the modern communications and transportation systems necessary to be competitive on a global scale.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers University-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- History of the United Nations Headquarters (PDF, United Nations)

- Report of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations, 1945-46 (United Nations)

- Headquarters of the United Nations Agreement between the United States and the United Nations, 1947 (PDF, U.S. Department of State)

- United Nations Association of Greater Philadelphia