Islam

Essay

Islam, a religion founded by the Prophet Muhammad in the early seventh century in the Arabian Peninsula, has had a presence in the greater Philadelphia region since the colonial era, but the number of Muslims locally did not grow significantly until after the 1960s. By the 2010s, when Muslims in the United States numbered more than three million, the Philadelphia region had the second-highest concentration of Muslims among American metropolitan areas, behind only Detroit. Area Muslims have represented a wide variety of religious orientations (Sunni, Salafi, Shiʿa, Sufi, and more) and races and ethnicities including African American, Asian, and Arab. Reflecting national trends, Muslims have ranked among the fastest-growing religious groups in the region.

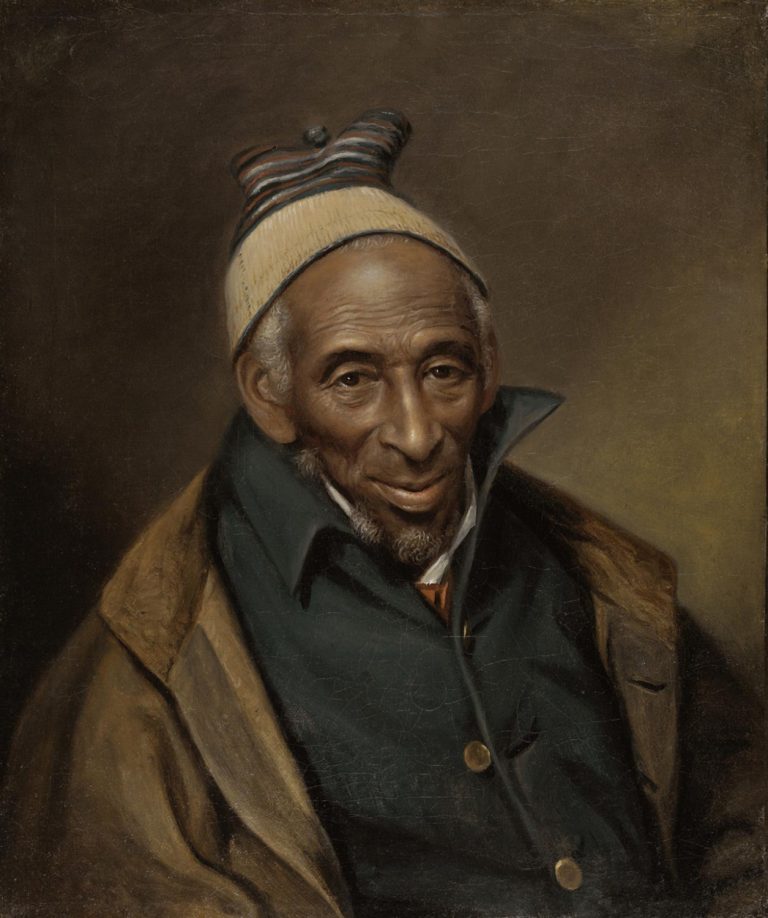

In 1682, William Penn (1644-1718) founded Pennsylvania as a colony that welcomed religious diversity. This diversity no doubt increased in 1762 when slave ships carrying nearly 500 individuals from West Africa, including from areas known to have significant Muslim populations, arrived in the Delaware Valley. Little knowledge about Muslims during the colonial era has survived, but scholars have estimated that as many as 10 to 30 percent of enslaved persons brought to North America during the slave trade were Muslim. In Philadelphia persons of African descent were known to partake in traditional drumming, singing, praying, and burial rituals in the area later known as Washington Square. If the Islamic call to prayer was ever sung in colonial Philadelphia, it might have been there.

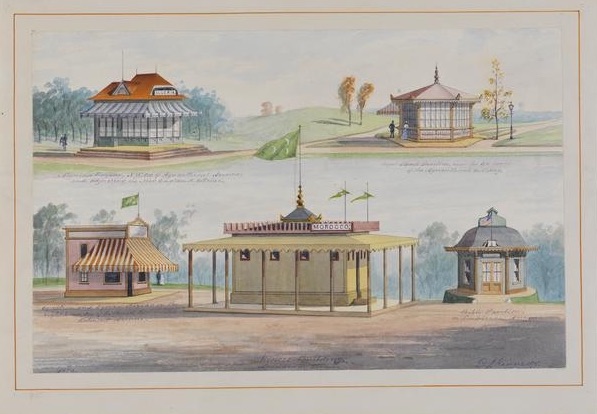

The first Muslims of non-African descent began to arrive in the late nineteenth century, mostly from the Ottoman Empire. The 1876 Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia drew exhibitors from all over world, including over 1,600 Arab traders and artisans who came to sell Tunisian coffee, olivewood rosaries, and various other trinkets from the Holy Land. The event sparked a wave of immigration to the United States from the Arab world. A small Lebanese community began to form in South Philadelphia in the 1880s, although the majority were not Muslim but Maronite Catholic. Immigration from the Middle East slowed to a trickle with the U.S. immigration restrictions implemented in 1924.

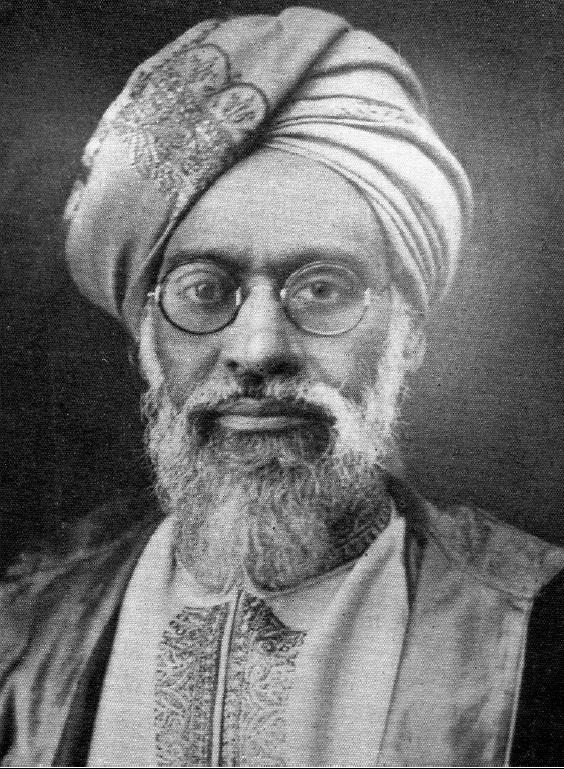

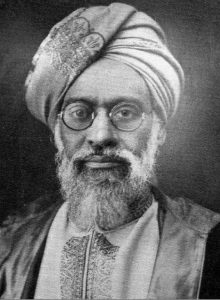

First Muslim Missionary

The first known Muslim missionary to the U.S. was Mufti Muhammad Sadiq (1872-1957), who arrived in Philadelphia in 1920. Sadiq was born in India and was a devotee of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908), who had claimed to be the most recent prophet of God. A charismatic speaker, Sadiq earned several hundred converts, both white and black, in cities throughout the United States, including at least 19 while imprisoned at an immigration center in Gloucester, New Jersey.

Religious innovation and experimentation increased during the early twentieth-century Great Migration of African Americans from the rural south to America’s urban North. Philadelphia, Chester, Camden, and Trenton all experienced rapid increases in the number of African Americans, many of whom were drawn to factory work during the First and Second World Wars. These changing cities became fertile ground for Islamic ideas and practices to take root.

The Islam-inspired Moorish Science Temple (MST) movement originated in Newark, New Jersey, in 1913, but also had a presence in Philadelphia. Founded by the Prophet Noble Drew Ali, MST aimed to disconnect African Americans from the legacy of slavery and define their identity not as “Negroes,” but Moorish Americans. Ali established communities around the country, including Philadelphia, where he founded Temple #11 in 1928. Temples frequently operated with the direct support of businesses, many of which were operated by women. The neighborhood of Twentieth and South Streets in Philadelphia was an early center of the movement, but Temple #11 later moved to North Fifth Street.

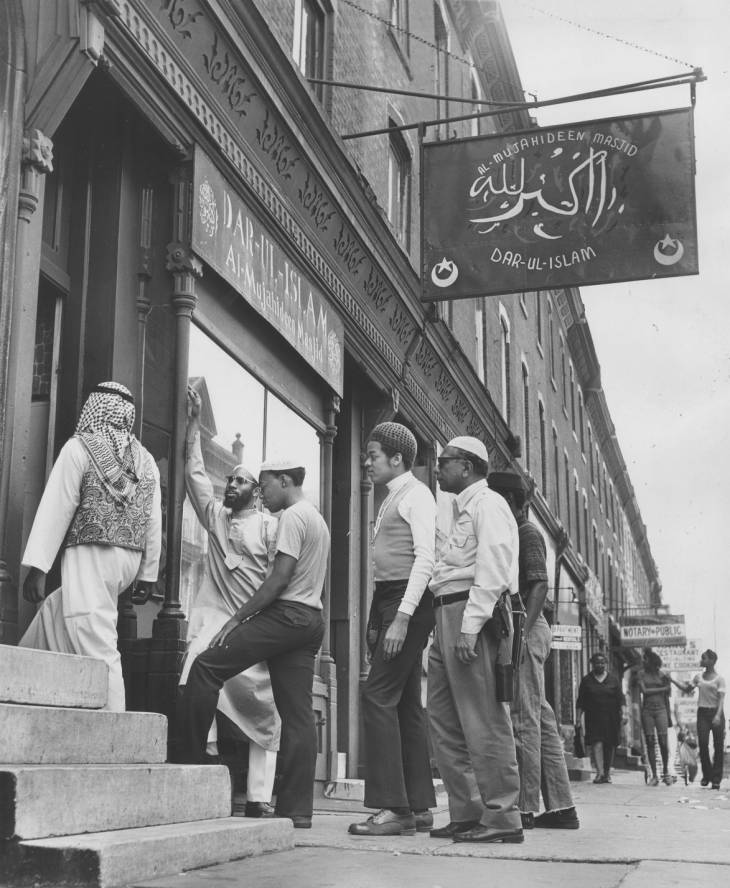

Traditional Sunni Islam began to take root among Philadelphia’s African Americans in the 1940s. Former MST member Muhammad Ezladeen (1886-1957), founder of Addeynu Allahe Universal Arabic Association (AAUAA), co-led one of the first national gatherings of African American Sunni Muslims in 1943 in Philadelphia. Around this time, AAUAA established an Islamic agrarian community in Hammonton, New Jersey. In 1949, Imam Nasir Ahmed, leader of the Hammonton community, founded the International Muslim Brotherhood in South Philadelphia, the first mosque in the region. The mosque later moved to West Philadelphia’s Lancaster Avenue and opened the Quba Institute, which became an early center for Islamic education.

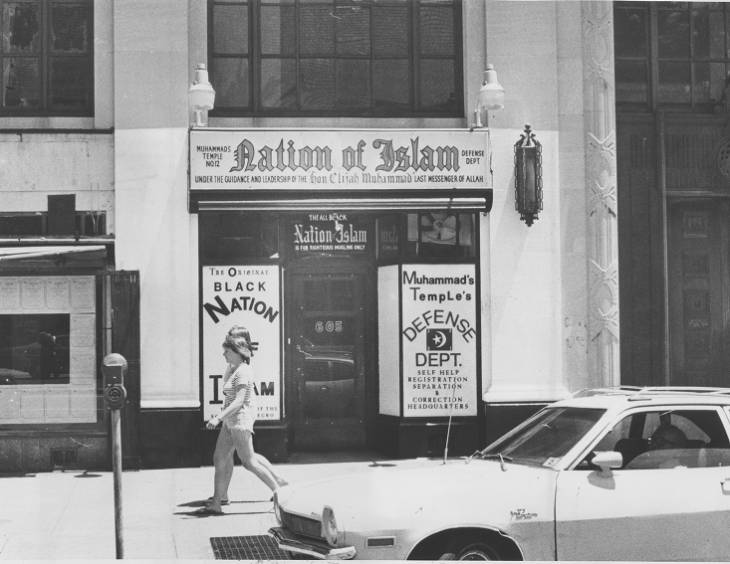

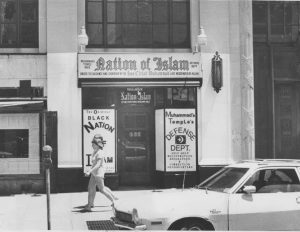

Nation of Islam

It was the non-orthodox, non-Sunni, Nation of Islam (NOI), however, that became the most visible expression of Islam among the region’s African Americans during the 1950s and 1960s. The NOI traced its origins to Detroit and the teachings of Wallace D. Fard (1877-1934?) and his successor Elijah Muhammad (1897-1975). They taught a mythology of black supremacy, which appealed to many disenfranchised African Americans who suffered under Jim Crow segregation and other forms of racial discrimination. The NOI established Temple #12 in Philadelphia after a 1954 visit by Malcolm X (1925-1965), who converted to NOI in prison. Five other temples were opened in following years.

Shortly before he was killed in 1965, Malcolm X rejected the racial mythology of the NOI and converted to traditional Sunni Islam after his pilgrimage to Mecca. Others followed his lead including Warith Deen Muhammad (1933-2008), the son of Elijah Muhammad, who in 1975 dismantled the Nation of Islam and called its adherents to embrace mainstream Sunni Islam, which emphasized racial equality. By 2017, there were more than two dozen Sunni Islam mosques that catered primarily to African Americans in the greater Philadelphia region, including Masjid Freehaven in Lawnside, New Jersey, and Masjidullah on Philadelphia’s Limekiln Pike.

Only a small percentage of American Muslims embraced the conservative Salafi tradition popular in Saudi Arabia, but by 2017 there were eight such mosques in the region, including the Germantown Masjid. Most Salafi Muslims were African American and tended to eschew political involvement and focus on individual religious obligations understood to conform to the practices of the earliest followers of Islam. Salafi Islam gained popular currency and support through proselytization efforts in local prisons and jails.

Although African Americans made up the largest number of Muslims in the United States in the mid-twentieth century, the dynamics changed after 1965 immigration reform opened the door to immigrants from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. As of 2011, approximately 33 percent of Muslims in the United States were South Asian, 27 percent Arab, and 24 percent were African American. The Philadelphia region gained from the new immigration. In 2010, the Association of Religion Data Archives listed 76,326 Muslims and 73 mosques in the Philadelphia region. By 2017, reports from local Muslim leaders suggested that more than 100,000 lived in the Delaware Valley.

Shifting Face of Islam

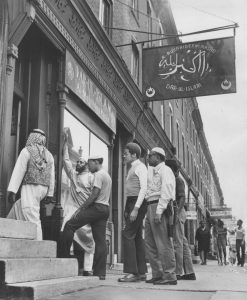

In Philadelphia, African Americans continued to make up a largest proportion of area Muslims, but the Muslim profile was changing. A handful of Palestinian immigrants arrived in Philadelphia following the Arab-Israeli War in 1948, but larger numbers immigrated to the region in the 1970s following the Yom Kippur War. Imam Hatip Jemali (n.d.), an Albanian Muslim, brought his family in 1966 and founded a mosque on Girard Avenue in 1974. Palestinian immigrants formed a small Muslim enclave in Philadelphia’s Lower Kensington neighborhood and founded the Al-Aqsa mosque in 1992. Palestinians, along with Egyptians and North Africans, formed enclaves in Philadelphia’s Feltonville neighborhood and along Bustleton Pike in Northeast Philadelphia. As of 2010, approximately 30,000 to 50,000 Arab Americans lived in the Greater Philadelphia region. The newest arrivals from the Arab world were refugees driven from conflicts in Iraq and Syria and predominantly Muslim.

Muslim African immigrants fleeing conflict in places like Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Sudan began arriving in larger numbers in the 1980s and 1990s. They tended to settle in West and Southwest Philadelphia, Delaware County, and Trenton.

Immigrants from Bangladesh started arriving in significant numbers after the country gained independence in 1971. The Bangladesh Association of Delaware Valley was established that same year. Bangladeshis have settled throughout the region but have concentrated pockets in West Philadelphia and the small Delaware County community of Milbourne. South Asians, including those from India and Pakistan, constitute most Muslims residing in the region’s suburbs.

Although most of the estimated 15,000 Indonesians in the region were Christian, according to the 2010 census, approximately 10 percent were Muslim, some of whom were affiliated with a mosque near Seventeenth and Tasker Streets in South Philadelphia.

As of 2017 five Shiʿa mosques in the area attracted both Farsi-speaking Iranians and Urdu speakers from India and Pakistan. The Imam Ali Masjid in Pennsauken, New Jersey, was frequented by Iranians and the Tri-State Bab-ul-ilm Islamic Center of Delaware served South Asians in Wilmington.

Sufi Communities

Immigrant communities also established Sufi Muslim communities such as the Bawa Muhaiyadeen Fellowship in the Overbrook section of Philadelphia. M. R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (1900-1986) came to Philadelphia in 1971 from Sri Lanka and formed a diverse community of spiritual seekers who practiced a Sufi ritual known as dhikr, or the recitation of the ninety-nine names of God. In 1984, the fellowship constructed a mosque. When Bawa Muhaiyadeen died two years later, a shrine was constructed near Coatesville, Pennsylvania. Although many traditional Sunnis consider Sufi shrines forbidden, the Bawa shrine has become a pilgrimage site for Muslims who seek a divine blessing.

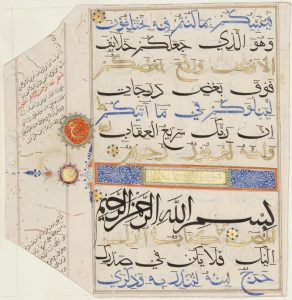

Sunni Muslims must pray five times daily and typically do so in homes and mosques with spaces oriented toward Mecca, the holiest center of Islam. Communal prayers are only required during the Friday Jumuʿah service, which includes a sermon delivered by the imam (prayer leader) or guest speaker. In most mosques in the region, men and women pray separately.

Muslims are free to pray at any mosque, but African Americans have tended to affiliate with one mosque through membership. Mosque affiliation has been somewhat more fluid among immigrant Muslims, but mosques will solicit zakat, or donations, to support their ministries. Mosques in the Philadelphia region are quite diverse in architectural styles, and most are converted spaces that were once churches, synagogues, or even former warehouses and commercial spaces. One example of a mosque built from ground up is the Ahmadiyya mosque in North Philadelphia.

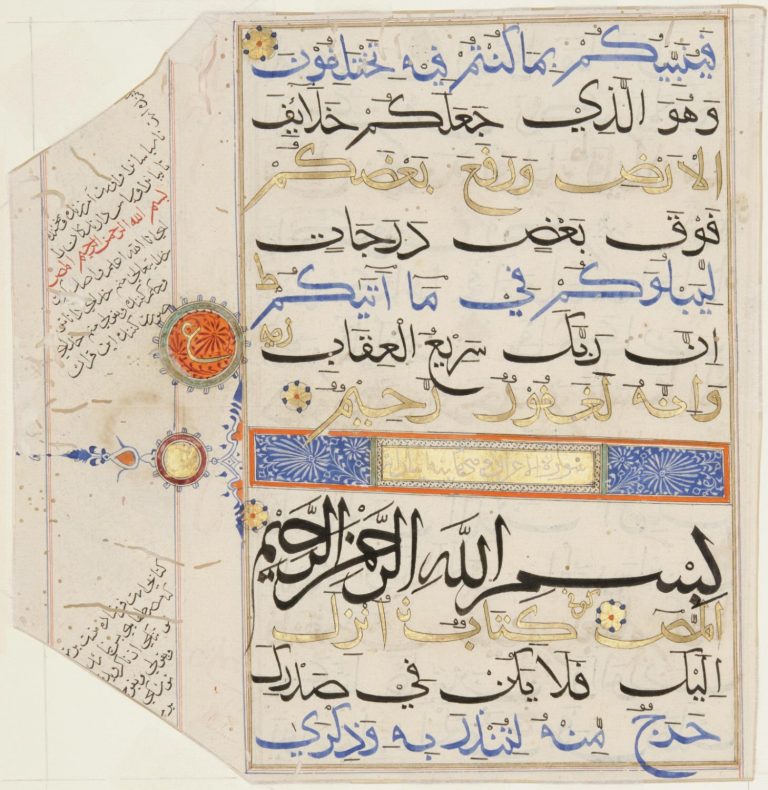

The home is also a place to practice the Islamic faith. According to one study of African American families in Philadelphia-style row homes, Muslims typically decorate their living spaces with Islamic texts and calligraphy, ask visitors to remove their shoes upon entering their homes, and consume their meals while seated on floor cushions.

Abstention Practices

Most Muslims abstain from alcohol and pork and only consume meat that is considered halal (permissible). As of 2017, there were dozens of markets, restaurants, and even food carts in the region that specialized in halal food. Mainstream supermarkets increasingly offered halal options during the 2010s.

For area Muslims, clothing styles have varied widely and have depended on cultural preferences and religious orientations. Conservative Salafi women (typically African American) have often worn long, black abayas (dresses), hijabs (head scarves), and niqabs (face coverings). For most Muslim women, the head scarf was the only visible marker of Islamic identity. As of 2017, as many as 40 percent of Muslim women were wearing no head covering at all. Muslim men were similarly diverse in their fashion choices with some donning Saudi-style kufis (skull caps), thobs (long shirts), and kifayas (scarves) and others wearing South Asian-style waist coats, and izars (skirts). Some combined these elements with American hip hop styles featuring t-shirts and Timberland boots. Long beards also became popular among African American Muslim men in the 2010s. The style worn by local Muslim hip hop artist Freeway inspired a national trend known as the “Sunni” or the “Philly Beard.”

Da’wah, or the teaching and preaching of Islam, is directed toward both Muslims (to remind them of their religious obligations) and non-Muslims (proselytization). Islamic education takes place in mosques, primary and secondary schools, university student associations, and public spaces at large. Mosques often offer classes on reciting the Quran, or studying the Sunnah (the teachings and actions of Islam’s founder the Prophet Muhammad). At mosques and schools, Muslims also get guidance on a wide range of topics including family life, manners, and prayer.

One of the earliest pioneers of Islamic education in the U.S. was Sister Clara Muhammad (1899-1972), wife of Elijah Muhammad (1897-1975), who founded one of her schools next to a West Philadelphia park named in her honor. As of 2017, several Islamic schools operated in the region: Al-Aqsa Islamic Academy, the Islamic School of Trenton, and even a Montessori school located on Villanova University’s campus. Students in these schools are taught standard academic topics as required by state guidelines but they incorporate Islamic teaching as well.

Muslim Student Associations

At the higher education level, the Muslim Student Associations (MSA) formed at universities and colleges throughout the region starting in the 1960s. One of the first was at the University of Pennsylvania’s campus in 1963, which has provided dedicated prayer spaces for Muslim students, chaplain services, and opportunities to educate the broader public about Islam.

One of the Philadelphia area’s most famous Muslim voices was the Temple University scholar Ismail Faruqi (1921-1986), who was murdered in 1986. The Palestinian-born Faruqi argued that immigrant Muslims had an obligation to spread the Islamic values of justice in the American public square. Although Faruqi drew criticism for his anti-Zionist politics and his Wahabist interpretation of Islam, most Muslims have believed that it was important to be invested in American society and have a positive impact on the larger community. Mosques have taken a lead in providing social services, spurring community development, and fostering political engagement.

Area mosques have taken important leadership roles in interfaith initiatives such as the political organizing group Philadelphians Organized to Witness, Empower, and Rebuild. Imams also have been represented on the Religious Leaders Council of Greater Philadelphia. Al-Aqsa mosque was central in establishing the annual Philadelphia Interfaith Walk for Peace and Reconciliation. Since 2004, several hundred participants, including Jews, Muslims, Christians, and others, have marched each year to demonstrate interfaith solidarity. The Pennsylvania branch of the Turkish American Peace Islands Institute (PII) has hosted interfaith dinners during Ramadan, lectures, conferences, and even interfaith trips to Turkey. The PII is affiliated with the Sufi-oriented educational activist Fetullah Gülen (1941- ), who has resided at a Pocono Mountain retreat center since 1999. Gulen, as the ostensible leader of the Gulen Movement, or Hizmet, which had a large following in Turkey, gained international attention in 2016 when the Turkish government accused him of masterminding an attempted coup and demanded that the U.S. government extradite him for trial in Turkey. Gulen has denied any such involvement in the coup.

Scrutiny After 9/11

After the terrorist attacks on 9/11 in 2001, U.S. law enforcement put Muslims across the country under closer scrutiny. In 2011, attacks took place at Muslims and Islamic sites, but after one such incident in 2015, when someone placed a severed pig head in front of the door of a Philadelphia mosque, many neighbors rallied in support of Muslims in their midst. Some in the Arab Muslim community proactively in built positive relations with the police. The Muslim American Society began an annual breakfast for area police officers.

Several local entities, including the City of Philadelphia’s office of Immigrant Affairs and Human Relations Commission, sought to support and protect Muslims and, particularly, Muslim immigrants. The Nationalities Services Center and the HIAS Pennsylvania assisted refugees and immigrants to meet the challenges of adapting to American life. The Center for American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) established a Philadelphia branch in 2004 with the aim of advocating for the civil rights of Muslims and challenging stereotypes about Islam in the media.

In the Philadelphia region, several Muslims reached high levels of government leadership, including being elected to the Pennsylvania State Senate in 2016, serving as Philadelphia’s police commissioner from 2002-2008, and taking office as a Philadelphia City Councilman in 2008. The political influence of local Muslims became clear in 2016 when Muslim leaders successfully persuaded the Philadelphia School District to recognize two Muslim holidays, Eid al-Fitr at the end of Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha after the hajj pilgrimage.

After 9/11, many non-Muslim Americans came to view Muslims in a more positive light. However, the number of anti-Muslim hate groups in the U.S. several such groups in the Philadelphia region. Philadelphia has a long history of welcoming religious minorities from around the world, but it has also experienced outbursts of xenophobia (exemplified by the burning of Catholic immigrant churches during the Nativist Riots of the 1840s). Although William Penn’s vision of a “holy experiment” where diverse religious groups might live together in harmony has never been perfectly implemented, Muslims have sought its promise in settling in the region and practicing their own faith.

David M. Krueger, who earned his Ph.D. in religion from Temple University, is an independent historian of religion and serves as a scholar consultant on religious pluralism for the Dialogue Institute. (Author information current at time of publication).

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Seeds of Awakening: The Rise of Islam in Philadelphia (scribe.org)

- Peeling Back the Layers on Malcom X's Mosque #12 (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Moorish Science Temple of America (World Religions and Spirituality Project)

- Ramadan in Philadelphia's African American Community (Aljazeera)

- PhilaPlace: Al-Aqsa Islamic Society (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)