Horticulture

By Eliza Butler | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The history of horticulture in Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley has been primarily a story of exploration, beautification, and preservation. Due to the relatively mild climate and fertile soils of the region, Native American groups practiced horticulture long before the arrival of Europeans. Colonists brought gardening traditions from their homelands and ushered in a new age of horticultural exploration. William Penn (1644-1718) imagined Philadelphia as a “greene country town” by way of horticulture with “gardens round each house, that it might never be burned, and always be wholesome.” By the end of the nineteenth century, horticulture grew to be not only a popular pastime but also a major commercial enterprise. As this commercial focus continued into the twentieth century, horticulture also became a strategy for preserving (and creating) green spaces.

Derived from the Latin hortus, “garden,” and colere, “to cultivate,” horticulture is the study and cultivation of plants for both beauty and utility. Horticulture encompasses activities like garden design, botanical study, and small-scale cultivation of crops (as opposed to the large-scale farming techniques of agriculture). Professional and amateur horticulturalists alike take care of forests, orchards, and arboretums, tend to vegetable and flower gardens, and cultivate species for sale or for study. While preserving and enhancing the beauty of a specific environment, horticulture also is key to maintaining a sustainable and safe food supply.

New Discoveries and Foreign Imports

In pre-contact North America, the Delaware Valley provided ample resources for the semi-agricultural communities of the Eastern Woodlands. In contrast to the hunter-gatherers of the Plains, the Lenni Lenape grew maize, beans, and squash and collected fruits and leaves from around 200 species of trees, vines, and shrubs. They fertilized their gardens with fish scraps. Although there seems to be no evidence of crop rotations, the Lenapes’ gardens changed as they moved from one village to the next, which they did frequently.

When European colonists arrived in the seventeenth century, they quickly established their own gardens to grow fruits, vegetables, medicinal herbs, and ornamental flowers. Many of the species grown in colonial gardens were transplanted from Europe. Local species were, however, foraged from the surrounding oak, hickory, and chestnut forests around the region’s small settlements. In addition to serving as a major staple of the colonists’ diet, these plants were also exported as Europeans developed an insatiable taste for colonial plants such as phlox, asters, and sunflowers.

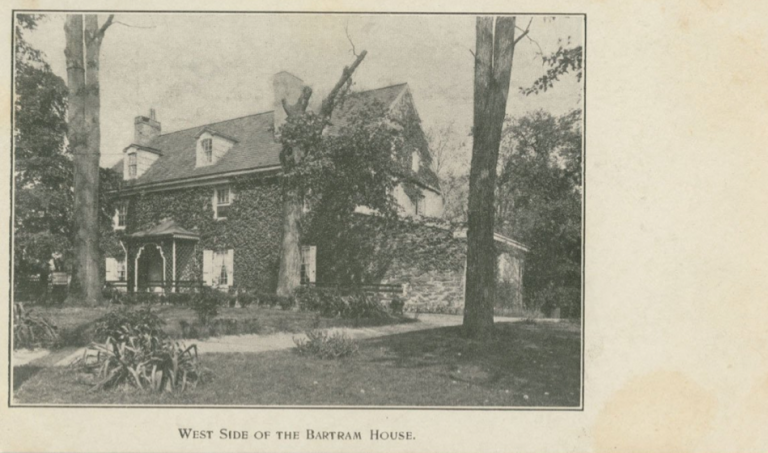

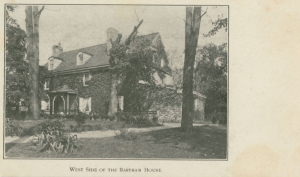

Some colonists created extensive gardens with a greater diversity of species than most typical colonial gardens. These early versions of botanical gardens were meant for study and, in the case of Quakers like John Bartram (1699-1777), for representing the diversity of God’s creation. Bartram developed the most famous North American garden of this period on the banks of the Schuylkill River in 1728. There he grew and arranged local species as well as others he collected on expeditions along the eastern seaboard, accompanied by his son William (1739-1823), who illustrated the specimens they found. The Bartrams and other enthusiasts exchanged seeds, plants, and botanical information with scientists in Europe such as Peter Collinson (1694-1768), beginning an important transatlantic dialogue about horticulture. William’s drawings became a crucial means of disseminating horticultural information in particular. In his rendering of Franklinia alatamaha, a typical example of botanical illustration from this period, William depicted only a small portion of this rare North American tree to emphasize the intricacies of its blossom and leaves so that the plant might be easily identified by others.

Bartram was not the only Philadelphian to create large-scale (and usually private) gardens in this period. Henry Pratt (1761-1838) designed his Lemon Hill estate to be a “showplace” with almost three thousand plants of seven hundred varieties. Other early botanic gardens included Tyler Arboretum, originally the farm of Jacob (b. 1814) and Minshall (b. 1801) Painter. The Painter brothers, interested in the study of natural history, collected dried plant specimens throughout their lives and in 1825 began planting more than 1,000 varieties of trees and shrubs on their property for study. In 1800 the DuPont family of Delaware started their first garden on two acres of land that later became part of the grounds for the Hagley Museum and Library.

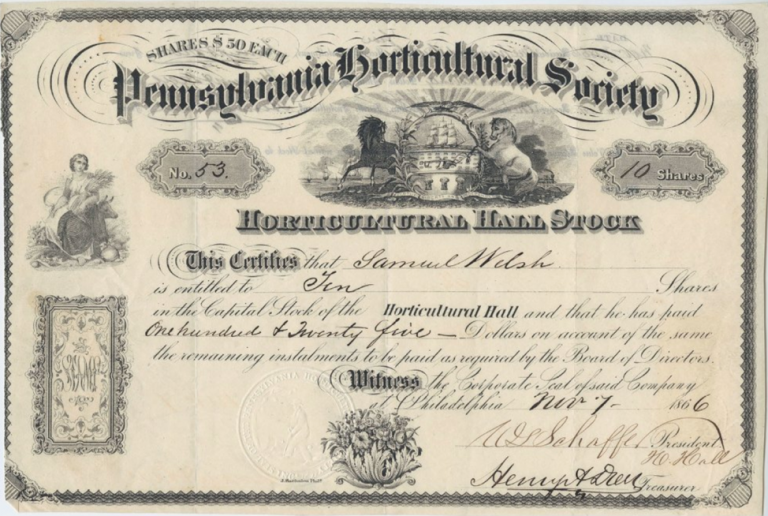

Early in the nineteenth century, local horticulture enthusiasts began to organize. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) formed in 1827 as a means of sharing information about plants and garden design. Members exchanged seeds and grafts from each other and abroad, tested new technologies and pesticides, and tasted new varieties and uses of fruits and vegetables.

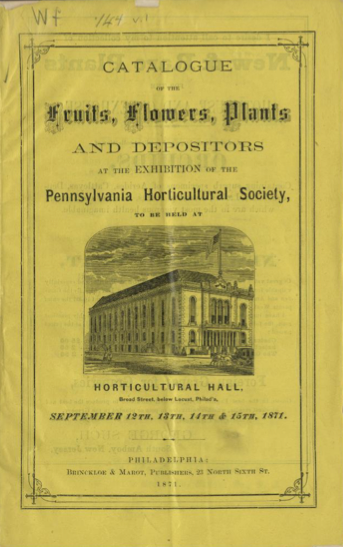

In the early days, members frequently brought new or particularly large species of plants to show off at meetings. In 1829, the society founded the long-running Philadelphia Flower Show when it hosted an exhibition at the Masonic Hall on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia to provide local growers the opportunity to display such specimens to the general public. Considered the first public flower show held in the United States, the event featured species ranging from Sickle pears to amaryllis to geraniums.

Many of these varieties, both local and imported, held great importance for horticulturalists in this period. Philadelphia painter Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860), for instance, documented the local interest in horticulture by depicting his botanist brother, Rubens (1784-1865), holding a potted geranium in a portrait from 1801. With both Rubens and the geranium rendered in exacting detail, the work functioned as a portrait not just of Rubens but also of the flower, a variety of Pelargonium inquinans. Imported from South Africa by way of Britain, this was the first tropical geranium cultivated in the New World and therefore a major challenge for a Philadelphian to grow.

Popularizing Horticulture for the Home Grower

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the New York-based landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52) described Philadelphia as “the first city in point of horticulture in the United States.” The early establishment of a horticultural community in and around the city as well as the incorporation of large estates into public parks, Downing argued, caused Philadelphia to develop more rapidly into a center for horticulture than other major North American cities. In addition, by the middle of the century Philadelphia became known for its horticultural publications, such as the influential Gardener’s Monthly, published in the city from 1859 to 1888 and edited by the Philadelphia botanist and nurseryman Thomas Meehan (1826-1901).

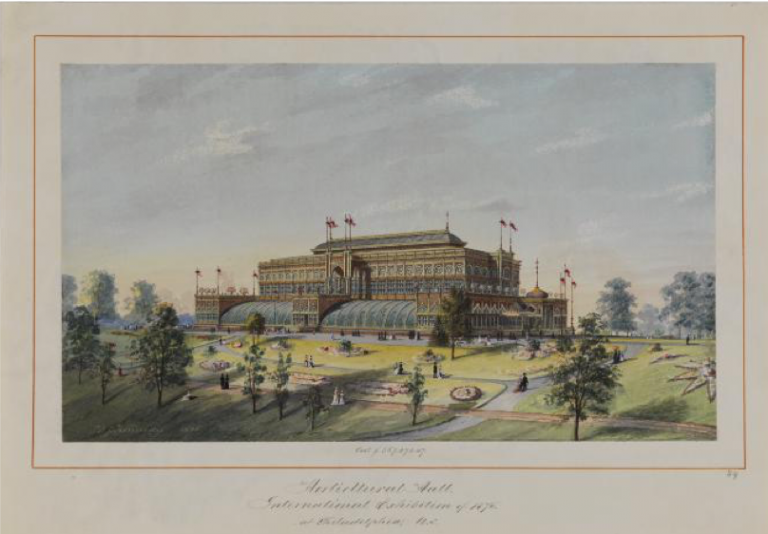

At the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, a 75,000-square-foot Horticultural Hall—the largest conservatory in the world—further marked Philadelphia as the nation’s center of horticultural activity. Inside, amateur and professional gardeners from the United States and eleven other countries displayed tropical plants, fruits, vegetables, and gardening tools and equipment. Tropical plants and fruits testified to advancements in transporting plants. Ferneries and aquatic flowers (not to mention waxwork flowers) created a spectacle amidst other varieties. The popularity of Horticultural Hall, with more than 1,800 species on view, spurred development of arboretums and botanical gardens around the country.

The promotion of horticulture, particularly floriculture, at the fair also spurred the development of nurseries and seed houses in the second half of the nineteenth century. Philadelphia had long been a major center of commercial horticulture activity. It was home to the first seed house in the country, founded by David Landreth (1752-1828) in 1784, and Bartram’s garden operated as a modern nursery by 1783. Later, Robert Buist (1805-80) of Philadelphia opened Rosedale nurseries, known for its roses and indoor plants, and Meehan began the successful Germantown Nurseries in the 1850s. By the 1890s, commercial horticulture in the greater Philadelphia area reached new heights as it became internationally known as home to the largest seed house in the world, the W. Atlee Burpee Company.

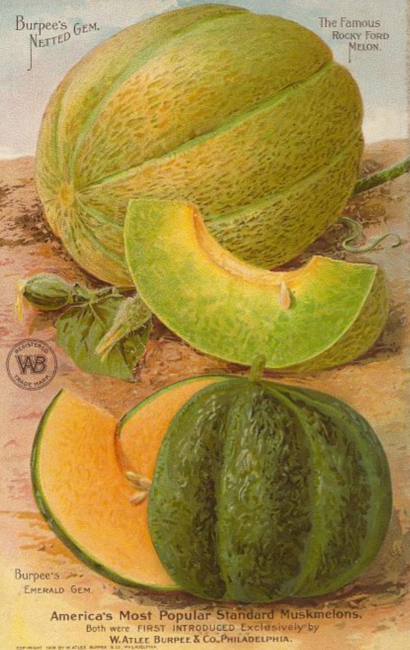

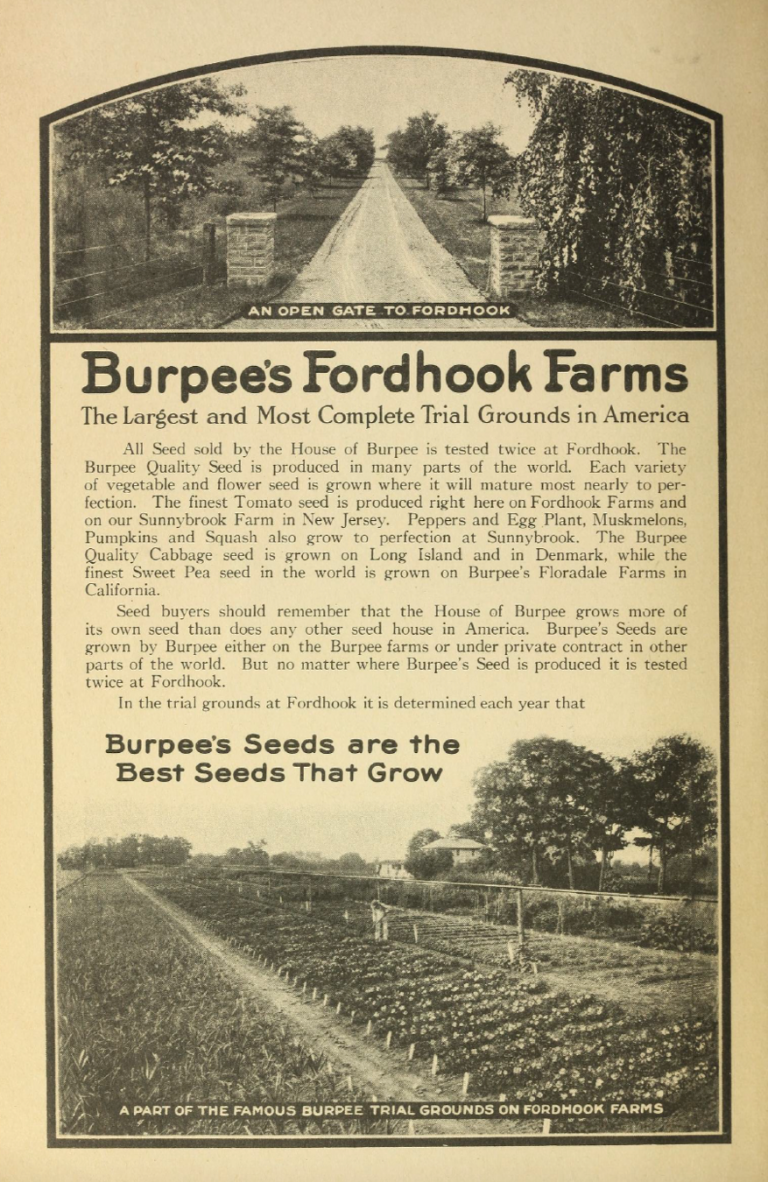

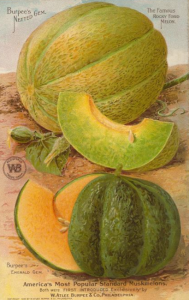

Begun by W. Atlee Burpee (1858-1915) as a mail-order poultry business, Burpee later switched to seeds as it proved to be a more profitable venture. Vegetable seeds became Burpee’s most popular product for home gardeners living in rural areas and emerging suburbs in the Northeast, Great Lakes, and Plains states. To promote his business, each year Burpee published a catalog filled with colorful illustrations and descriptions of vegetables and flowers. An illustration of the “Rocky Ford melon” and the “Emerald Gem,” for instance, with an up

-close depiction of one whole and another partially dissected large green melon resting in a melon patch emphasized the successful growing outcomes of Burpee’s varieties (as did distinctive names). A large part of Burpee’s success lay in his experimental farms, the first of their kind in the United States. In 1888, he established Fordhook in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, where, taking advantage of the exceptional growing conditions, he developed and cultivated new varieties of plants, for example, the “stringless green pod bush bean” and “iceberg lettuce.” In 1909 he began two other experimental farms, one in California and the other, Sunnybrook, in Swedesboro, New Jersey.

Seed houses like Burpee succeeded because of the gardening movement taking place in the United States at the turn of the century. As urbanites moved to the suburbs to escape the pollution and overcrowding of the cities, middle- and upper-class homeowners, especially women, became more and more interested in gardening the landscape around their homes. Groups of amateurs formed garden clubs like the Philadelphia Botanical Club (founded in 1891), the Garden Club of Philadelphia (founded in 1904), and the Garden Club of Wilmington (founded in 1918). The Garden Club of America began in Germantown in 1913. Amateur and professional degree programs also began to proliferate at this time. Women played an important role in establishing horticultural education with Jane Bowne Haines (1869-1937) opening the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women in 1910 and Laura Barnes (1875-1966) opening the Barnes School of Horticulture in the 1940s. The region’s state universities later instituted Master Gardener training programs in Pennsylvania (Penn State, 1982), New Jersey (Rutgers, 1984), and Delaware (University of Delaware, 1986).

The Preservation Impulse

While the commercialization of horticulture maintained a steady pace into the twentieth century, attention also turned toward preservation. Beginning in the second half of the century, municipal, state, federal, and private organizations acted to preserve the gardens and parks in Philadelphia and the surrounding region of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. In addition to ongoing preservation of areas such as Fairmount Park and Bartram’s Garden, these conservation efforts and a revived interest in native species spurred the development and preservation of nature reserves and native or wildflower gardens. The Brandywine Conservancy, founded in 1967, created a garden around the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, to pay tribute to native species. Mt. Cuba Center, a woodland wildflower refuge in Hockessin, Delaware, became a public garden in 2001.

Other preservation efforts have been organized at the local level. The Philadelphia Green program, started by the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society in 1974, has created community gardens and small parks in neighborhoods across the city. Vacant lots have been turned into vegetable and flower gardens, and trees have been planted in a number of low-income neighborhoods, renewing interest in horticulture in these communities. The Philadelphia Orchard Project, founded in 2007, focused on planting and preserving community orchards. In southern New Jersey, the Camden City Garden Club began in 1985 to assist Camden residents with community gardening projects. It later turned its attention to educating younger generations about horticulture with its Grow Lab program and the Camden Children’s Garden, a four-acre “horticultural playground.” In the twenty-first century, professional and amateur horticulturists in the greater Philadelphia area continued, as they had for centuries, to use gardening as a means of beautifying urban spaces, encouraging the exploration of nature, and building communities.

Eliza Butler is a Core Lecturer in Art History at Columbia University. Her research centers on the intersection of landscape, natural history, and material culture in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century North America. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- In photos: Bike trail unveiled at Bartram’s Garden (WHYY, June 21, 2012)

- Wood artists salvage beauty from destruction at Bartram’s Garden (WHYY, May 2, 2014)

- Philadelphia Orchard Project (WHYY, June 18, 2015)

- ‘The Pomona Fund’ marks two milestones for Philadelphia Orchard Project (WHYY, December 31, 2015)

- Make mulch, not war: Philadelphia Flower Show to spread ‘Flower Power’ (January 16. 2019)

- Philly Flower Show leads visitors back to the garden in Woodstock celebration (WHYY, March 1, 2019)

- Australian florist crowned world champion at the Philadelphia Flower Show (WHYY, March 4. 2019)

- New horticultural center at Overbrook School for the Blind seeds a connection with nature (WHYY, May 9, 2019)

Links

- Debt and Consequence (Philly History Blog)

- Andrew Eastwick: Savior of Bartram’s Garden (Philly History Blog)

- Across From Flower Show, A Building Built By Flowers Blooms Again (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Demise and Demolition of Horticultural Hall (Philly History Blog)

- Praising Horticultural Hall in Fairmount Park (Philly History Blog)

- PhilaPlace: Las Parcelas and Colobo Community Gardens (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women (ExplorePAHistory)

- Pennsylvania Horticultural Society

- Master Gardener Program (Penn State Extension)

- Master Gardener Program (New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, Rutgers University)

- Master Gardener Volunteers (University of Delaware Cooperative Extension)

- Landscape Architecture and Horticulture Programs (Tyler School of Art, Temple University)

- Barnes Foundation Horticulture Certificate Program