City of Neighborhoods

Essay

William Penn, the founder of Philadelphia, grew up in the Tower Hill section of London, one of the many storied neighborhoods in the capital of England. Before Penn set foot on the Delaware River shoreline in October 1682, he lived in a number of European cities including Paris, Dublin, and Amsterdam. Each of those centuries-old European cities contained a rich fabric of fabled neighborhoods.

Curiously, the moniker of “The City of Neighborhoods” is carried by the city Penn founded instead of one of the European cities where firmly established neighborhoods existed long before Philadelphia was even a figment in Penn’s imagination.

New York City, formally founded before Penn’s arrival in America, has hundreds more identified neighborhoods than Philadelphia, judging by the list of nearly two hundred neighborhood names compiled by the Philadelphia City Department of Records. In New York, for example, there are nearly ninety neighborhoods in Queens, one of the five boroughs comprising America’s largest city. Yet New York’s Department of City Planning references America’s largest city merely as “A City of Neighborhoods” – not using “the” as a distinguishing word as Philadelphia does. Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, and other cities also regard themselves as “a” City of Neighborhoods.

Origins of “Neighborhoods” Label Unclear

The origins of Philadelphia’s claim as “The City of Neighborhoods” are unclear. The city was regarded as “The City of Homes” as far back as the 1870s, and an 1893 book termed Philadelphia “a city of residences” with praise for the legacy of homeownership by “employers and employees” dating from Penn’s arrival. A 1976 booklet on the historical development of Philadelphia neighborhoods published by Philadelphia’s City Planning Commission stated, “Philadelphia as a city of neighborhoods has antecedents as far back as the city’s founding.”

Referencing Philadelphia as “The City of Neighborhoods” – whether the savvy snagging of an adroit marketing slogan or sheer happenstance – is consistent with the fact that historically Philadelphia has a track record of defining itself through its residential character.

Implicit in Philadelphia’s “City of Neighborhoods” dynamic is the intense pride Philadelphians hold regarding the distinct residential communities comprising this city. While Philadelphians love their city they particularly love those sections of their city where they were born, raised, and in many instances continue to live.

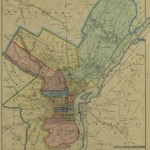

Many of the current neighborhoods around Philadelphia existed as separate boroughs, districts, or townships in the County of Philadelphia before absorption into the city via the 1854 Act of Consolidation. Until that time, the city’s boundaries followed Penn’s original plan, extending from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River and from Vine to South Streets.

Tacony Is Oldest

The distinction of being Philadelphia’s oldest continuously occupied neighborhood belongs to Tacony, with records of residents dating from a decade prior to William Penn’s arrival. This neighborhood located along the Delaware River, in what is now Philadelphia’s Lower Northeast section, is near the place where Penn made a Treaty of Peace with the Native Americans who originally inhabited the Philadelphia region.

Consolidation brought previously separate jurisdictions into the city such as Spring Garden on the northwest edge of Penn’s original city boundaries and historic Germantown, formally founded one year before William Penn’s arrival.

Germantown, eight miles outside the original boundaries of Philadelphia, retains evidence of its past in its many historic buildings, including a house George Washington used during his presidency. Spring Garden, now a middle-class neighborhood, in the twentieth century gained an additional designation as the “Art Museum Area” for its location near the famed Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Neighborhoods also formed through transportation innovations and real estate development. Mount Airy, in Philadelphia’s leafy Northwest section, inherited its name from the mansion owned by a Colonial-era Chief Justice of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court. But it expanded residentially in the late 1800s, spurred partly by the extension of trolley and commuter train lines from the city core. Girard Estates, in South Philadelphia, arose in the early 1900s when the City of Philadelphia built rental homes on land once owned by banker Stephen Girard, the richest man in the United States when he died in 1831.

Byberry Known for Abolitionist Leanings

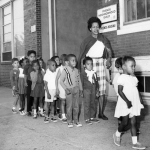

Byberry, in the Far Northeast section, was the most rural section of Philadelphia County at the time of the 1854 Consolidation and had a vibrant abolitionist/anti-slavery presence prior to the Civil War. One of the nation’s first protests against school segregation occurred there in 1853 when a wealthy African American, the richest resident in that community, refused to pay taxes and forced town leaders to quickly reverse their edict on banning black children from the public school.

Philadelphia neighborhoods appear to be stable, yet they are continually changing.

This is evident in Society Hill, the lauded upscale community of colonial-era homes adjacent to Independence National Historical Park. The name Society Hill originated with the Free Society of Traders, a colonial-era merchant’s society, and once applied to the entire region from today’s Pine Street down to Christian Street. The name fell out of use by the nineteenth century, but assumed new life during the 1950s period of urban renewal.

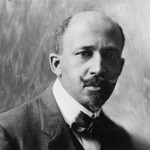

Urban renewal transformed Society Hill from a hardscrabble residential area filled with commercial buildings into an elite enclave. However, that renewal also triggered removal of Philadelphia’s oldest African American community dating from colonial times – the area examined in Dr. W.E.B. DuBois’ seminal 1899 book, The Philadelphia Negro, prepared as sociological research for the University of Pennsylvania.

Powelton Village, a West Philadelphia neighborhood north of Drexel University and adjacent to Thirtieth Street Station, began its residential life in the late 1800s as a location desired by some of the city’s industrial tycoons. After some descent on the economic ladder, Powelton Village again gained distinction as the locus for Philadelphia’s counter-culture and anti-Vietnam War scenes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Currently Powelton Village, with streets lined with Victorian-era homes and a listing on the National Register of Historic Places, enjoys a quiet residential character.

Other neighborhoods have physically disappeared.

Wissahickon Residents Bought Out

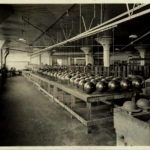

The rugged wilderness-like Wissahickon Valley in Fairmount Park, listed as a National Natural Landmark, once contained residential clusters of housing for workers in the scores of water-powered mills along the Wissahickon Creek. During the late nineteenth century, the housing and mills were razed as the Fairmount Park Commission bought land to preserve the purity of the creek for Philadelphia’s water supply.

During the 1980s a large section of Logan was demolished because homes built there decades earlier were constructed on unstable ground, causing the foundations to sink and some houses to collapse. That razing of nearly 1,000 homes left an eerie landscape of street grids with no structures.

Surprisingly for a city steeped in history, the neighborhood-memory of most Philadelphians extends back for only a couple of decades. Neighborhood histories sometimes become lost as populations and places change, but new histories are constantly being created.

Few among the thousands coming to the Sports Complex in South Philadelphia yearly to cheer the city’s professional baseball team are aware that Philadelphia’s century-plus-long baseball tradition began in North Philadelphia during the nineteenth century.

Beginning in the 1870s, North Philly housed six of the thirteen facilities used by the city’s professional baseball teams. Two teams from that era remain active in Major League Baseball, including the Phillies, who played in North Philly until Veterans Stadium opened in South Philadelphia in 1971. The other is the American League team once known as the Philadelphia Athletics, now the Oakland Athletics following a move to the Midwest in the 1950s and then to the West Coast.

Pastoral North Philadelphia

North Philadelphia, although identified in the public mind as quintessentially inner-city urban, began as a rural pastoral area.

North Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion section, once known as Summerville, traces its name to a mansion-housed restaurant that once served strawberries and cream to wealthy guests in the nineteenth century. In a placid park section on the western edge of Strawberry Mansion are a series of architecturally significant colonial-era mansions located on ridges overlooking the Schuylkill River.

Now overwhelmingly African American, in the first half of the twentieth century Strawberry Mansion housed Philadelphia’s largest Jewish community, numbering more than 30,000 residents. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, the neighborhood’s total population dropped to 22,562, and 97.58 percent of those residents were African American. Whites in Strawberry Mansion – of all religious and ethnic groupings – comprised less than one-half of one percent of the community’s population.

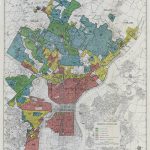

Successive waves of immigrants from across Europe, blacks migrating from the South, and Latinos (primarily Puerto Ricans) have added distinctive imprints on the complexions of neighborhoods.

Many currently think of Philadelphia’s Latino community as historically rooted in northeastern North Philadelphia and western Kensington, but there is also a fading memory of the once-vibrant Puerto Rican presence in Spring Garden, evidenced by the Roberto Clemente Playground. That facility honors Clemente, the Puerto Rican-born professional baseball star and respected humanitarian, who was the first Latino selected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. (Interestingly, Clemente has no direct connection to Philadelphia.)

Many see South Philadelphia as historically the Italian section of the city. Few are aware of that area’s origins with Swedish settlers as evidenced by the Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) Church, the oldest church in Pennsylvania. And along with Italians, the area has growing Mexican and Southeast Asian populations.

Asian Immigration

Most recently, immigration from East Asian countries like Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam expanded the business ownership complexion of Philadelphia’s Chinatown, located in Center City a few blocks east of City Hall, and other city neighborhoods.

Ironically, Philadelphia’s famous nickname – the “City of Brotherly Love,” derived from the translation of the Greek name Penn gave his city – masks a history of un-neighborly turmoil.

Philadelphia’s earliest turf-related race riots targeted African Americans in today’s Society Hill in the early nineteenth century, and by the 1840s anti-Catholic sentiment targeted Irish immigrants in Kensington and Southwark.

In the 1950s and 1960s efforts to preserve racial integration by staunching “white flight” became defining struggles in neighborhoods like Mount Airy and the Wynnefield section of West Philadelphia. Today Mount Airy is widely recognized as a national model for an integrated neighborhood.

In the 1980s some politicians in Philadelphia’s Northeast mounted a campaign to have that section secede from the city and become an entity known as Liberty County. Secession supporters cited their feeling of being overtaxed but receiving short-shrift in city services. Critics of the movement claimed the campaign rested in part on a desire to sustain the then-overwhelming white population character of that sprawling area, which built up residentially largely after World War II.

The proposed state legislation to create the separate Liberty County died from inaction. In the decades that followed, diversity in the Northeast increased with non-whites from other sections of Philadelphia and immigrants from Russia and other countries.

The dawn of the twenty-first century did not lessen turf-related tensions. South Philadelphia High School witnessed attacks on Asian students by black classmates and tensions roiled in Southwest Philadelphia between blacks and immigrants from African countries.

Neighborhoods are sometimes places of conflict but at the same time they remain sources of pride. The heartfelt loyalty held by Philadelphians about their neighborhoods radiates through the collective psyche of the city. That loyalty animates the Philly-centric sense of place and purpose manifest in an emotional swagger referenced locally as “Attytood.”

“Attytood” is a driving force in Philadelphia, contributing to national reputations for the love of local cuisine like juicy cheesesteaks and dry soft pretzels and the often-raucous sports fans’ allegiances to local professional sports teams. Consistent with “Attytood.” the name for the mascot of Philadelphia’s Major League Baseball team is the “Phillie Phanatic.”

Although Philadelphia’s population fluctuates and the features of its communities change, the pride in being a part of a neighborhood remains resilient.

Linn Washington Jr. is Associate Professor of Journalism at Temple University and Co-Director of Philadelphianeighborhoods.com. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.