Society Hill

Essay

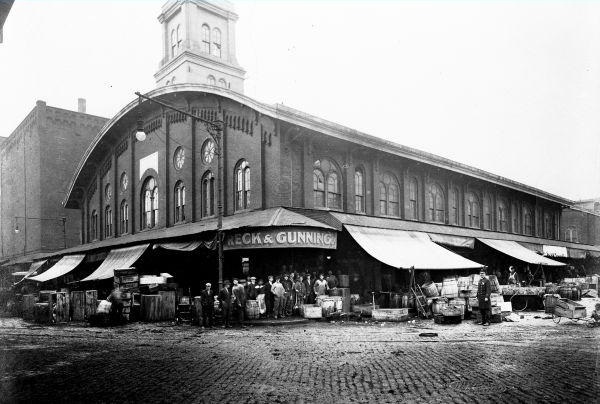

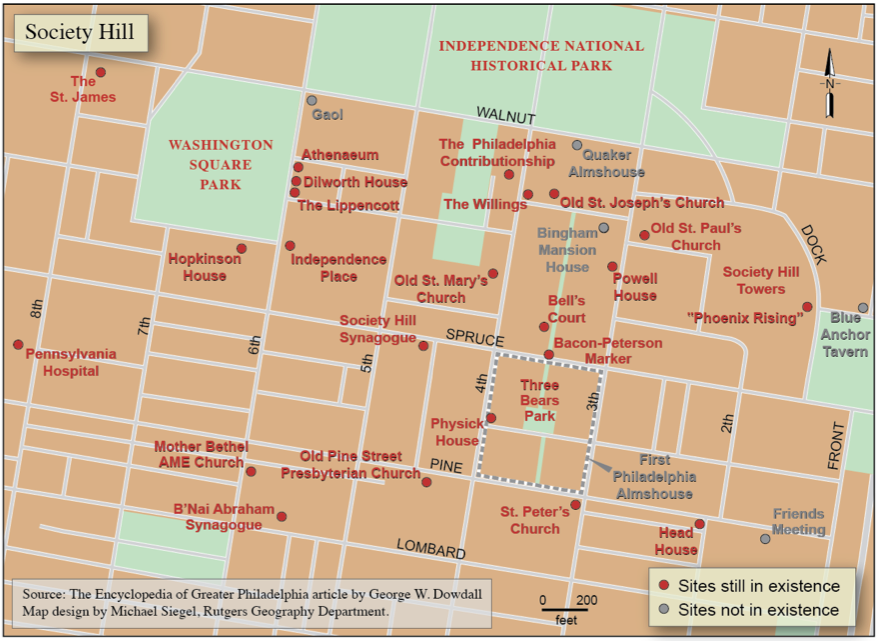

Society Hill is one of Philadelphia’s oldest neighborhoods, with more buildings surviving from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries than any other in the country. Usually defined by the boundaries of Walnut, Lombard, Front and Eighth Streets, this area south of Independence National Historic Park evolved over the centuries as a diverse, complex residential and commercial neighborhood. Although deteriorated by the 1950s, it was reborn as a city historic district and attracted international attention for its innovative combination of urban renewal and preservation.

Society Hill’s history begins in 1682, when William Penn first set foot in his new colony at the point where Dock Creek poured into the Delaware, near the Blue Anchor Tavern. To spur development, he gave a charter to “The Society of Free Traders” and a strip of land in the same area, which became part of the new city of Philadelphia when Penn’s surveyor sketched the grid centered on High Street (now Market), a few blocks north. The Society flew its flag on the top of a small hill that soon become known as “The Society’s Hill.”

All social classes and both enslaved and free Blacks moved to the growing neighborhood, with larger houses on the main streets and smaller quarters filling in back streets and alleys soon added to the grid. By 1776, the neighborhood had a diverse population. The elite built freestanding mansions such as the Physick House and town houses such as the Powel House. Close by were smaller structures for servants and workers, particularly those from the nearby waterfront. Farther inland were the homes of tradesman, craftsmen, and others.

Some of the city’s first public and community institutions took root here. The growing population prompted construction of a new market, which started with shambles (sheds) on Second Street in 1745 and gained a Head House in 1804. The neighborhood added churches of various denominations such as the Friends Meeting (a Quaker meeting house), St. Peter’s (Anglican), Old St. Joseph’s (Roman Catholic), and Old Pine Street Church (Presbyterian). Richard Allen founded Mother Bethel, home church of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, there. A Quaker and a public almshouse (predecessor to the city’s first public hospital and its large state hospital, Byberry) housed the poor, Pennsylvania Hospital (the first private hospital in the country) tended the sick, and the gaol, or the Walnut Street jail or prison, held prisoners and debtors. The Athenaeum, a member-supported library and museum, opened. Economic activities ranged from the port to taverns, the first insurance company, and the offices of investors, physicians, and attorneys. The diversity of people and interests also led to clashes, most famously a large anti-Catholic riot in 1844, part of a broader conflict between nativists and Catholics in the city.

The Fifth Ward

Once called the Dock Ward, the area came to be defined as the Fifth Ward, a designation that fit it until well after World War II. By 1860, 24,792 lived there. The population declined to just over 7,000 people by 1950, largely due to outmigration to the suburbs. By 2010, the population was just over 6,000 people.

The population mixture changed as well. As Philadelphia grew, commerce and elite families moved westward, away from Society Hill. Always home to some African Americans, the ward’s southwest corner blended into the large African American community of the old Seventh Ward. This area was the primary subject of W.E.B. Du Bois’s (1868-1963) seminal sociological study of an urban neighborhood, The Philadelphia Negro (1899). He wrote that by the end of the nineteenth century the Fifth Ward was the worst Negro slum in the entire city, comparing it to a “cess-pool.”

During the late nineteenth century, the old Fifth Ward also became an important part of the city’s Jewish Quarter. Synagogues and Jewish newspapers and community institutions filled what is now Society Hill’s southern half, as Jewish immigrants crowded into the neighborhood. Indicative of the ethnic succession in Society Hill, in 1916, a historic Baptist church was renamed the “The Great Roumanian Shul” (as spelled out in Hebrew across the present façade of the Society Hill Synagogue).

In 1900, the old Fifth Ward housed an often impoverished population, with all of the health and social problems attendant to that. At the same time, the area remained a mixed-use neighborhood with commercial and industrial establishments such as a wholesale food market located at Dock Street and warehouses and light manufacturing nearby. Several publishers worked out of large buildings fronting Washington Square, and the insurance industry expanded along Chestnut Street. The area near Willings Alley was the home to the headquarters of three of the country’s largest railroads.

The Great Depression accelerated the old Fifth Ward’s transformation. Redlining limited investment, and colonial and federal houses were outfitted with storefronts and fire escapes and used as shops and rooming houses. A purveyor of hog bristles purchased the Powel House, intending to convert it into an “outdoor garage.” Preservationists saved the historic structure from that fate by acquiring it and operating it as a museum. But after World War II, as work disappeared from its factories and port, the old Fifth Ward sank further, with its councilman claiming Dock Street was a virtual skid row. The market was filthy, dilapidated, and congested.

Creating the New “Society Hill”

Political reform swept over Philadelphia after World War II. Mayors Joseph Clarke (1901–90) and Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) led an effort to renew the city beginning with its badly decayed Center City. The city located a new food distribution center elsewhere. Mayor Dilworth built a house in the colonial style on Washington Square and moved his family there, hoping such actions would encourage others to convert what was viewed as a dirty and dangerous “has been” area of an urban core into a place of renewal.

Led by city planner Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), an urban renewal plan gave a major role to restoration of many of the early residences. Bacon’s plan included the demolition of many nonresidential buildings and the creation of “greenways.” The hope was that several high-rise buildings such as Society Hill Towers, new single homes and developments that complemented colonial homes, red brick sidewalks and Franklin lamps, a new market near Head House Square, and a supermarket and shops all would help to draw in families. New organizations such as the Philadelphia Historical Commission and the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation were created to certify historic houses and acquire property and then resell it to owners who agreed to follow strict preservation guidelines. By adopting a historic preservation urban renewal strategy of saving an entire neighborhood, not only individual homes, Philadelphia built upon the precedents of historic districts created in Charleston, S.C., Savannah, Georgia, and elsewhere. Locally, leaders such as Charles E. Peterson (1906–2004), employed by the National Park Service during creation of nearby Independence National Historical Park, joined Bacon in spearheading the effort. But Bacon insisted on incorporating greenways and new construction in modernist style, such as the high-rise Society Hill Towers and Hopkinson House, to create a neighborhood distinctly different from a collection of historic buildings.

Peterson renamed the old Fifth Ward as “Society Hill” as part of rebranding of the area and an investment strategy. Newspaper stories of urban pioneers who had used their own labor or funds to refurbish historic structures helped change its image. But another reality was also present: Most of the African American renters were displaced from the area; merchants opposed closing their businesses; and one resident later talked about the area before renewal as “a fun little neighborhood.” In Society Hill, as elsewhere in urban America, gentrification also meant dislocation as wealthier individuals and lenders pushed older residents out. Property

values and rents rose. The later story line for Society Hill, however, became one of private initiative more than government effort remaking a city neighborhood. After all, banks, contractors, and corporations like Alcoa Aluminum had provided much of the capital for Society Hill’s renewal.

Plans to create a Crosstown Expressway would have leveled the South Street neighborhood, while off-ramps for Interstate 95 would have taken a corner of Society Hill. Older residents opposed to renewal and newer residents supportive of it combined their organizations into the Society Hill Civic Association in 1965, joining others in successfully opposing the expressway and ramps. Society Hill was nominated as an official city historic district in 1999, helping guard its historical character by vigilant review of zoning and historic preservation standards.

The area went from being well below the poverty line to one of the city’s most affluent neighborhoods. By 2014 its population included a higher proportion of senior citizens, foreign born, and households without children than before renewal. Recent changes have included more tall buildings such as Independence Place and a wave of conversions of nonresidential buildings into condos, such as the former headquarters of the Reading Railroad transformed into a luxury condo building (The Willings). A 45-story tower (The Saint James) arose behind the façade of a nineteenth–century bank. But high-rise projects have not succeeded everywhere. For example, efforts to construct a tower behind the Dilworth House have so far been stopped in the courts.

Over more than three centuries, Society Hill evolved from a mixed-use neighborhood of a colonial town, to a big city ward that contained skid row and slum, and now to a gentrified “gold coast.” Its recent history includes a largely successful effort to return it to a former glory as an urbane village of historic homes (and, now, luxury high-rises), but one largely stripped of the industrial, commercial, and civic institutions and the visible racial and ethnic minorities that once filled its streets.

George W. Dowdall is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University and Adjunct Fellow, Center for Public Health Initiatives, University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Edmund Bacon, architect of modern Philadelphia , and champion of skateboarders [audio] (WHYY, May 22, 2013)

- A master plan for Society Hill proposes new design guidelines--and downzoning (WHYY, July 19, 2018)

- Society Hill residents lose zoning fight over high-rise (PlanPhilly via WHYY, February 6, 2019)

Links

- Preserving Society Hill

- Dock Street's Transformation into Society Hill (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Urban Renewal: The Remaking of Society Hill (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Uprooting Philadelphians (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Reviving Society Hill (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Form, Design, and the City (1962) (Philadelphia Department of Records)

- Pennsylvania Hospital

- Abolitionist of Society Hill (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia Historic Districts

- Society Hill Civic Association

- Society Hill Synagogue

- The Tombstone Wall of Society Hill (Hidden City Philadelphia)