Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC)

Essay

The Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC), a nonprofit corporation controlled jointly by the city government and the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, formed in 1958 to support existing businesses and attract new ones by offering land and low-cost financing for both for-profit and nonprofit enterprises. To accomplish this mission, PIDC manages the oldest municipal land bank in the United States, pioneering a novel approach to assembling, upgrading, and marketing urban land to business owners.

During the 1950s the prevailing analysis of Philadelphia’s economic problem was that a lack of suitable land discouraged companies from expanding their plants and prevented new firms from moving into the city. Modern technology and production processes had made one-story factories more efficient than multistory industrial buildings. Investors favored one-story factories with convenient access to highways, off-street parking for employees, and easy loading and unloading of freight—all features more likely to be found in suburban locations than in the city’s congested industrial districts.

Elected in 1956, Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) made industrial renewal a top policy priority. In 1958 Dilworth secured the cooperation of the city’s Chamber of Commerce to establish PIDC as a jointly-controlled nonprofit corporation. The city and chamber each furnished half of its initial operating budget. PIDC also received financial support from state industrial-development programs.

Moving quickly and at times controversially, PIDC acquired an inventory of abandoned industrial sites, as well as undeveloped parcels that might prove attractive to new firms or expanding companies whose owners wanted to stay in Philadelphia. Often PIDC improved the sites with water, sewer, and street installations before selling them to manufacturers. PIDC then used the proceeds of those sales to create a revolving fund for further purchases. Most of this help went to small and medium-sized manufacturers and wholesalers in a wide variety of industries that reflected the historic diversity of the city’s economy: metal fabricators, publishers, machinists, food processors, makers of furniture, clothing, chemicals, and dozens of other products.

PIDC soon realized it would also have to help companies acquire financing in order to counteract the lure of suburban and Sunbelt locations, many of which offered financial incentives. Older plants, especially small family-owned businesses, suffered from declining property values in older industrial sections of the city. Their declining equity made it hard for them to borrow money for upgrades they needed in order to compete against suburban producers. PIDC found it could borrow money at below-market interest rates because the debt issued by municipalities is treated as tax-exempt by the federal government. Borrowing at low interest rates, PIDC could then lend to companies at similarly low interest rates. As historian Guian McKee has observed, that arrangement has meant over time that the subsidy enjoyed by PIDC’s client companies came largely from the federal government, not from local taxpayers.

PIDC used its inventory of land parcels combined with financial incentives to lure companies to large industrial parks it began creating at the edges of Philadelphia during the 1960s. Two prime examples are the Philadelphia Industrial Park created in the far northeast corner of the city and the Penrose Industrial District in the city’s southwest corner. Each was constructed on land originally set aside for the city’s two airports, but not needed for that purpose. These complexes provided the same modern buildings, landscaping, and ample parking as suburban industrial parks, with easier access to the city’s ports and airports. Not surprisingly, they attracted dozens of companies, including both new arrivals and older established firms wanting to expand.

PIDC also played a role in creating the nation’s first urban research park in 1963. As early as 1959 PIDC began pursuing that goal in partnership with the West Philadelphia Corporation (a nonprofit organization focused on drawing research and development activities to the area adjoining the universities in West Philadelphia). Hoping that the city’s combination of medical schools, along with pharmaceutical and chemical companies, could attract new research and development firms, PIDC and WPC together created a nonprofit entity, the University City Science Center, with a dual mission: to promote scientific, medical, and engineering research that could be commercialized, and to develop real estate that would attract companies and individuals engaged in those pursuits. Since the Science Center’s incorporation in 1963, PIDC has supported its growth with low-interest loans and other assistance for real estate development, in addition to funding early-stage companies bringing health care and life science technologies to market.

Starting in the 1970s, PIDC began devoting major efforts to reinforce downtown Philadelphia as the region’s commercial center. By the early 1970s it was becoming clear that business services were overtaking manufacturing as the backbone of the Philadelphia economy. PIDC added hotels, offices, shopping, entertainment, and commercial properties to its redevelopment agenda. For example, PIDC bought the Bellevue Stratford Hotel on South Broad Street when it closed after a 1976 outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease. That transaction allowed a critical property in a strategic location to be returned to productive use. Other commercial projects included the Market East Shopping Center known as the Gallery, along with downtown parking garages, movie theaters, and restaurants.

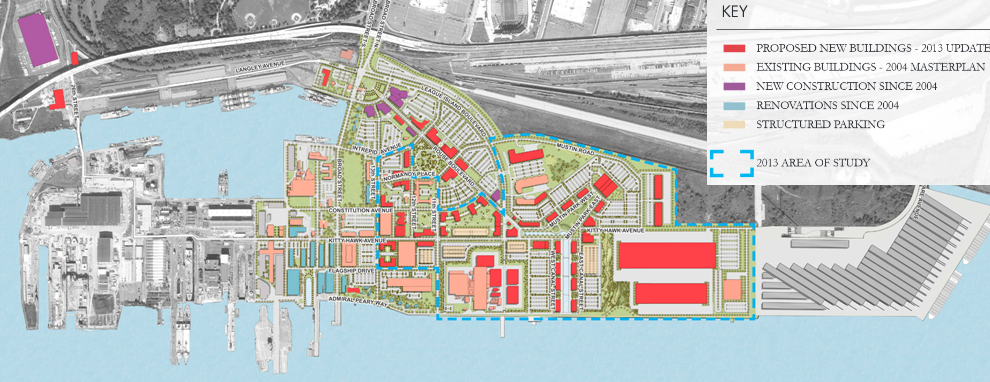

The largest of all PIDC endeavors is its ongoing campaign to redevelop 1,200 acres of land at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, which the federal government decommissioned after it had served for 125 years as a shipyard and naval base. When the Navy transferred ownership of the yard to the city in 2000, PIDC was assigned responsibility for transforming the enormous installation into a mixed-use campus with an emphasis on green technology. Combining office suites, manufacturing spaces, and research-and-development buildings, the area has benefited from $130 million in public investments for utilities, landscaping, roadways, and other infrastructure. PIDC has incorporated environmental values into its redevelopment, including LEED building design, advanced storm water management, preservation of open spaces, smart grid, and renewable power sources. More workers are now employed there than were employed by the naval shipyard before it closed.

Despite its record over more than fifty years of investment and job development, PIDC has its critics. Some have faulted PIDC for shifting manufacturing to industrial parks at the far edges of the city. In so doing, PIDC spurred job growth in locations only reachable by automobiles, and that requirement discouraged employment of low-income workers who did not own cars. Good-government advocates, including the city controller, have periodically complained that PIDC conducts its business without regard to the checks and balances that normally constrain government. As a separate nonprofit corporation, PIDC is able to circumvent debt-protection and bidding requirements and spend money outside of the usual appropriation process, without the transparency normally expected from government departments. Balancing such criticism is PIDC’s record of completing over 5,000 transactions involving 2,000 acres in land sales and about $8 billion in financing—numbers that increase each year as PIDC continues to attract business investment.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce

- A History of the University City Science Center Exhibit (University of Pennsylvania)

- Hotel Marks Surge of Navy Yard Development (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- A Lack of Postwar Investment (Philadelphia the Great Experiment)

- The Navy Yard

- The New Life of the Old Family Court (and its Murals) (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation

- PIDC and Manufacturing (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Science Center