Historic Germantown: New Knowledge

in a Very Old Neighborhood

By David W. Young | Places and New Knowledge

Essay

Located six miles northwest of downtown Philadelphia, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods. It is also one that offers provocative examples of how people consider the past. Originally part of 5,700 acres that William Penn sold to two groups from the Rhine region of what is now Germany, German Township was a processing center, made up of a diverse group of craftsmen and cottage industries, where raw materials from outlying counties were turned into finished goods for sale at market in Philadelphia. The development of Germantown laid the groundwork for two great constants in Germantown history—continual change in its population and a sense that Germantown was its own place, separate from Philadelphia. These constants have persisted from its earliest days to its current state as a largely African American community. These elements of change, however, have not always been reflected in the community’s “memory infrastructure,” its museums, monuments, and public memory. Recent research initiatives, though, have begun to produce new understandings of the history of Germantown.

Originally a township independent of Philadelphia, Germantown’s claims to national attention stem from several important events. The establishment of Germantown as a permanent German settlement in America in 1683 put into place William Penn’s bold ideas of religious toleration of different faiths in one colony, bringing Quakers to Pennsylvania together with Mennonites, Dunkards, and other groups that had been unwelcome in England and Continental Europe. In 1688 four Germantown settlers drafted a protest against slavery within the Dutch-German Quaker community that is considered to be the earliest antislavery document made public by whites in North America. The American Revolution saw one of the largest engagements of the war sprawl over Germantown’s streets in 1777. In the early American republic, Germantown provided the temporary home of President George Washington and his cabinet in 1793, which many years later became known as the “Germantown White House.” In many ways, Germantown’s history touches on several of the most salient chapters of America’s struggle for religious toleration, freedom, and independence.

Fourteen Historic Sites

Germantown’s history has frequently been the subject of regional and national attention. Architects working on the Depression-era Historic American Buildings Survey began the path-breaking national survey of historic structures by examining twelve houses in Germantown. The National Park Service has served as a steward of one Germantown site (the Deshler Morris House) since 1948 and the National Trust for Historic Preservation of another (Cliveden) since 1972. From the 1950s to the 1970s, some of the nation’s top urban planners devoted their energies to devise solutions to Germantown’s economic decline and population loss mostly based on capitalizing on its historic assets. Today, the presence of fourteen historic sites testifies to a century’s worth of preservation efforts. Those museums, however, have not always been interested in producing new knowledge; rather they preserved how life was lived long ago.

Until recently fourteen small museums of the consortium, Historic Germantown Preserved, have focused preservation, research, and programs primarily on colonial, revolutionary, and Victorian history. The neighborhood’s efforts at historic preservation can be seen as one continual Colonial Revival. Over the last decade, however, institutions founded upon one facet of interpretation are changing to incorporate new research and perspectives, extending the reach of historic interpretation while burrowing deeper to understand what Germantown was really like, in ways that speak to its current residents.

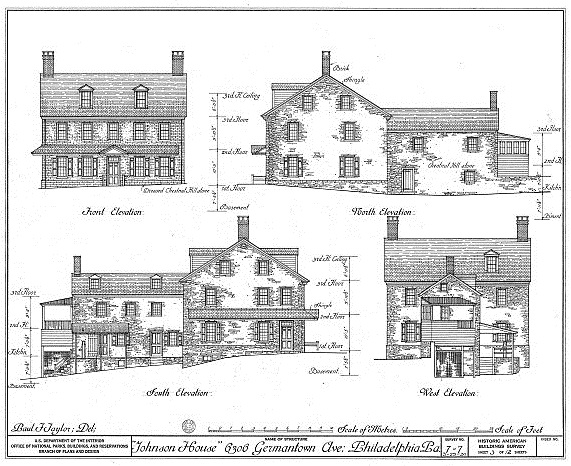

The first example of a historic house that changed its interpretation occurred at the Johnson House, a 1768 German-Dutch house that had been damaged in the 1777 Battle of Germantown. In the 1980s scholars discovered the house was a “station” on the Underground Railroad. While rumors had circulated for years that the Johnsons, a family of abolitionists, had helped freedom seekers hide on the family’s large property, strands of research into African American history and new social history coincided to establish that, in the 1850s, the house had served as a “station.” Neighborhood activists along with the museum community formed a board of directors to preserve the house and interpret it not for its period of construction, but for its significance as a site where the principles of the 1688 Germantown Protest Against Slavery were acted upon. In 1997 Johnson House was declared a National Historic Landmark for its role in the struggle for freedom.

In its centennial year, 2000, the Germantown Historical Society began initiatives to enhance its twentieth-century collections through a variety of ways. One has been the collection of oral histories of immigrant and in-migrant communities, particularly those of Italian Americans and African Americans. These stories reflect the experiences of people who moved to German Township and resulted in a collection that shows residents’ initiatives to end housing discrimination in the Mt. Airy section of German Township and to integrate through active initiatives by neighborhood associations. The projects resulted in a richer sense of diversity throughout the recent past, including ways of life in the pockets of Germantown which were frequently isolated from one another by prejudice or segregation.

Many institutions in Germantown have important histories. Church histories alone account for hundreds of community histories that profile the tapestry of diverse communities, from founding groups like Mennonites to newer, growing congregations in the Muslim community. Schools have also reflected the ways the neighborhood responded to newcomers. A research study of Germantown High School indicates its evolution over the course of the twentieth century reflected the demographic shifts, specifically charting neighborhood and ethnic backgrounds of students throughout the century. It puts into sharp relief how Germantown’s civil rights protests in the 1960s took shape with students calling for reforms about what kinds of history they were being taught.

History of Inter-Racial Programs

The recently closed YWCA, long a leading institution since its inception in 1917, has sparked research into its influence, particularly efforts to foster inter-racial programs for young people and to coordinate efforts between its white and Black branches. The YWCA was instrumental in creating collaboration among institutions in the star-studded “Negro Achievement Week” in 1928. This event, a forerunner of Black History Month, brought artistic and cultural leaders from the African American community to Germantown at a time of great racial volatility due to a large presence of the Ku Klux Klan. Such events are now being explored in the traditional historical community in ways that expand the memory infrastructure to include examination of the lives of all Germantown’s residents.

Cliveden is the largest house museum in Historic Germantown. Built by the Chew family in 1767, Cliveden opened to the public in 1972 and has been interpreted for its role in the 1777 battle, along with its treasured colonial furnishings and decorative arts. The Chew family’s wealth was based in large part on the fact that the family was among the largest, and latest, owners of enslaved Africans in Pennsylvania. The voluminous Chew Papers at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania have recently proved a wealth of information about specific individuals among the Chews’ enslaved Africans, the workings of plantations throughout the mid-Atlantic region, and the climate of violence necessary to manage plantation life. Research indicates active agency and manipulation of the system, as well as escapes, by enslaved people as early as the 1770s and 1780s, much earlier than most Underground Railroad accounts. Cliveden’s ability to tell the larger, more complex story of the struggle for freedom and independence, rather than just the site’s connections to the Revolution, greatly expands and deepens the sense of what Cliveden means to the neighborhood and the Philadelphia region and points to the major reorientation underway at Trust sites regarding interpreting “troubled pasts” and integrating the stories of slaves and servants into new narratives.

The consortium of Historic Germantown Preserved is best understood as a group of educational institutions with historic preservation at their core that continue to move toward a shared history of Germantown—something which has been largely lacking but whose potential is great. Such collaboration promises not only a more integrated history but also a more efficient and effective use of historical resources. It also serves to promote greater community investment in historic places as agents for community development. Indeed, the stories that continue to be uncovered through research and interpretation speak to audiences that are very different from early in the twentieth century. These efforts have produced new partnerships and connections that result in audiences very different from ones that visited house museum when they were considered sacred shrines to the past. Historic sites now actively partner with churches, businesses, community development corporations, and even the local police district to produce youth-serving programs, and thereby count not only museum visitors but also the many people served by created education programs in ways that build these sites from the past into the life of the neighborhood present.

David W. Young is a lecturer at University of Pennsylvania Graduate Program in Historic Preservation and Executive Director at Cliveden House in Historic Germantown. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2009, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Black History Month essay contest doubles as way to honor Germantown's "unsung heroes" (NewsWorks, February 17, 2014)

- Grassroots group seeks cash from wealth alumni to turn GHS plan into action (WHYY, February 28, 2014)

- Will Germantown ever become an accessible, big-time tourist draw? (WHYY, March 26, 2014)

- 'Challenges and opportunities' of gentrification discussed at weekend forum in Germantown (WHYY, April 28, 2014)

- A look inside Germantown High School during Thursday's open house (WHYY, May 22, 2014)

- Germantown residents to tourism officials: Update your website so people know we exist (WHYY, June 5, 2014)

- VisitPhilly officials will fix Germantown tourism oversights, tour neighborhood (WHYY, June 11, 2014)

- 'Germantown White House' temporarily reopens to the public on Saturday (WHYY, July 10, 2014)

- Historic Germantown welcomes Liberia native Trapeta Mayson as its new executive director (WHYY, August 26, 2014)

- Pending deal on former school catches Germantown High neighbors off guard (WHYY, September 19, 2014)

- Revolutionary Germantown Festival returns to Northwest Philly [gallery] (WHYY, October 6, 2014)

- First-ever tour takes visitors through historic cemeteries in Germantown (WHYY, October 13, 2014)

- Neighbors look to save historic Wissahickon Playground from destruction (WHYY, March 5, 2015)

- Philadelphia Cultural Fund helps support over 30 Northwest Philadelphia arts organizations (WHYY, May 11, 2015)

- In Germantown, real hope rises for better days ahead (WHYY, June 15, 2015)

- Juneteenth festival in Germantown celebrates the area's rich role in abolishing slavery (WHYY, June 22, 2015)

- Revolutionary Germantown Festival brings historic reenactment to Northwest Philly (WHYY, October 5, 2015)

- Couple’s commitment to save a historic Germantown home leads to a new vocation (WHYY, December 8, 2015)

- 'Revolution starts in Germantown' with modern public housing on Queen Lane (WHYY, December 15, 2015)