Italians and Italy

By Stefano Luconi | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

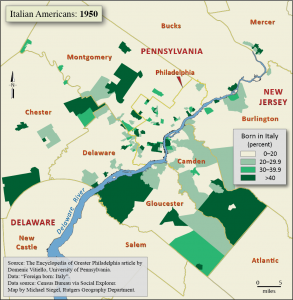

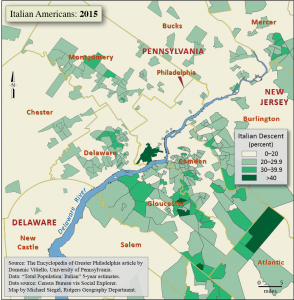

Although ties between Italy and Greater Philadelphia stretched back generations, it was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that Italian migration increased to the extent of forming visible points of settlement in the area. Over time, loosely connected clusters of Italians in various neighborhoods, mainly in South Philadelphia, coalesced into a singular ethnic community with Catholic parishes and beneficial associations eventually based on their members’ common national origin. While the city’s economy diversified, Italians spread to other locations in the Pennsylvania suburbs and in many parts of southern New Jersey. By 2010, the U.S. Census identified the Philadelphia metropolitan region as home to the second-largest Italian-American population in the United States with about 3,100 Italian immigrants living in the city and more than 142,000 residents identifying as having Italian ancestry. Well beyond the iconic neighborhood of South Philadelphia, with its Italian Market along Ninth Street, they sustained a presence in multiple forms and locations.

The earliest contacts between the Philadelphia region and Italy occurred during the seventeenth century. A handful of Waldensians, members of a Christian but non-Catholic movement, reportedly landed at New Castle (later included in Delaware) in 1665 to escape religious persecution in their native Piedmont. Both William Penn (1644-1718) and Francis Daniel Pastorius (1615-1720), the founder of Germantown, visited Italy and learned the language. Penn’s successors built on Pennsylvania’s record of freedom of conscience and self-government to lure prospective settlers from northern Italy. These benefits struck a sensitive chord among people who lived in part under foreign rule and subjected to the stifling presence of the Catholic Church. An endorsement from French enlightenment philosopher Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet, 1694-1778) contributed to keeping the idea of Pennsylvania freedoms alive in Italy in the mid-eighteenth century. So did subsequent travel accounts by political essayist Filippo Mazzei (1730-1816), a friend of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) who is credited with inspiring the concept that “all men are created equal,” as well as botanist and adventurer Luigi Castiglioni (1757-1832). Even a Catholic priest such as Francesco Soave (1743-1806) extolled the philanthropy of Pennsylvania’s Quakers in his influential moral novellas in the 1780s. It was, therefore, no surprise that Philadelphia became an early magnet for Italian emigrants to British North America, who could profit by trade routes connecting the city, albeit irregularly, to ports such as Genoa and Leghorn in their homeland.

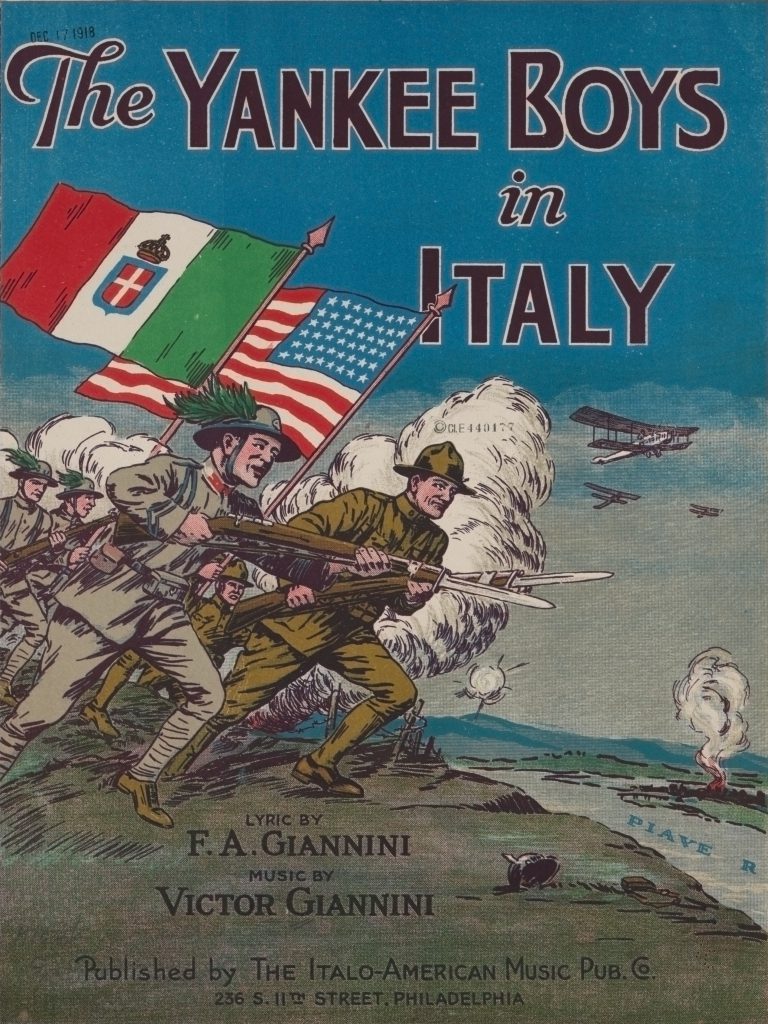

The first Italian who spent time in Philadelphia was probably John Palma (Giovanni di Palma), a composer who directed a concert in the city in 1757. Other musicians followed, along with some artists, scientists, intellectuals, merchants, artisans, vendors of plaster statues, and small entrepreneurs. Although The Directory of Philadelphia in 1791 listed only nine residents with Italian-sounding last names, it likely missed those who had Americanized their surnames as well as recent and temporary dwellers. In the same year, the Republic of Genoa appointed the first consul in Philadelphia from the Italian peninsula to assume responsibility for trade relations.

During the first half of the nineteenth century the Italian community grew slowly and contained mostly immigrants from Liguria and Tuscany. Many, such as Giacomo Sega (1794-1859) and Piero Maroncelli (1795-1846), were political exiles. They fled the northern regions of their motherland following the initial setbacks of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italy’s political unification, and went to the United States because independence had consolidated the nation’s image as a model of liberty and free government. In the Italian expatriates’ eyes, Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence had been signed and the federal Constitution had been drafted, became the epitome of U.S. freedom.

Skilled and Warmly Welcomed

These émigrés were skilled workers who quickly became fluent in English as they Americanized. As such, they were welcomed in Philadelphia and found opportunities to advocate and raise money for the cause of Italy’s self-rule. Further enhancing the initial climate of favorable regard for Italy and its immigrants, a number of prominent families included Italy in their “Grand Tours” of Europe.

The contingent of Italians numbered only a few more than one hundred residents in 1852, when they succeeded in persuading Bishop John Neumann (1811-60) to have St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi on Montrose Street established as the first Italian Catholic parish nationwide, with Gaetano Mariani (1800-66) as its pastor. Fifteen years later, the Società di Unione e Fratellanza Italiana opened its doors at 746 S. Eighth Street as the city’s first benevolent and fraternal Italian-American ethnic association. These two institutions offered the formal foundations for the subsequent development of an Italian community that, by 1870, comprised 516 people located in a neighborhood bounded by Christian, Seventh, Carpenter, and Ninth Streets in a South Philadelphia district where the price of real estate was lower than in other areas.

In contrast to earlier migrants who had come for political purposes, Italians who crossed the Atlantic after Italy’s 1861 unification aimed almost exclusively at improving their economic condition. The exodus resulted primarily from structural factors such as the country’s backward and poor agriculture and late industrial development. From the early 1880s to the mid-1920s, these immigrants were primarily unskilled laborers from peasant backgrounds in southern Italy, with a majority from the Abruzzi region, who pursued jobs in the city’s diversified and thriving economy. They got work primarily in railroad construction and maintenance as well as in the expanding textile and clothing industries until the outbreak of World War I, and later in the shipyards and subway construction. The period from the early 1880s to the mid-1920s marked the peak of the Italian mass migration to Philadelphia within an even larger flow to the United States as a whole. The city’s Italian-born population and its children grew from 10,023 in 1890 to 136,793 in 1920, while their area of settlement in South Philadelphia extended north to Bainbridge Street and southwestward to Federal Street along Passyunk Avenue. Additional but smaller communities sprang up in Manayunk, Roxborough, West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, Frankfort, Overbrook, Chestnut Hill, Mount Airy, Nicetown, Mayfair, and Germantown. Nearly half of these immigrants were “birds of passage” who moved back and forth between Italy and Philadelphia, as many planned to spend in their native land the money they expected to make in their adoptive country.

The mushrooming of new Italian Catholic parishes offered further evidence of the creation and growth of these colonies. St. Lucy was founded in Manayunk in 1906, Our Lady of the Angels in West Philadelphia in 1907, St. Donato in Overbook in 1910, Our Lady of the Rosary in Germantown in 1914, and Our Lady of Consolation in Frankford in 1917. By 1932 the Philadelphia archdiocese included as many as twenty-three Italian parishes.

Quarries and Railroads

Italians also settled in Norristown in the late 1880s to work in quarries and in railroad and construction gangs. They reached southern New Jersey, too. There, at summertime during temporary layoffs in the clothing firms in the slow season, garment operatives from Philadelphia picked berries in the fields around Hammonton and Vineland to supplement their annual income. Their presence, along with that of unskilled immigrant farm laborers, contributed to the growth of an Italian community in Camden, whose members were attracted by such major job providers as Campbell Soup Company, the New York Shipbuilding Corporation, and radio manufacturer RCA. Newcomers clustered primarily in the neighborhood of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Camden’s Bergen-Lanning district. This church became their national parish in 1903 and subsequently promoted a school and several service organizations.

Immigrants also took up residence in Wilmington in the late nineteenth century, although Delaware as a whole had as few as 459 Italians in 1890. Many arrived from Torino di Sangro, in the Abruzzi region, and from the Sicilian village of Ferla to work in fiber mills, at DuPont chemicals, and with the yards of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Their colony developed in the area around St. Anthony’s church, 901 Dupont Street, which became Wilmington’s Italian national parish in 1924.

Regardless of location, Italian districts were never fully insulated from other urban sections and also became home to residents from diverse ethnic backgrounds. For instance, in 1930, the average Philadelphian of Italian descent lived in a neighborhood where only 38 percent of the inhabitants were of Italian ancestry.

Social differentiation distinguished Philadelphia’s Italian settlements from their initial existence. A small middle-class of professionals (such as lawyers, physicians, store owners, and undertakers), who catered to their countrymen, emerged quite soon. These businessmen founded the Circolo Italiano in 1913 to promote their activities. A few construction workers managed to rise to the status of contractors, while other entrepreneurs surfaced in the sectors of food production and imports from Italy.

Charles C.A. Baldi Sr., Innovator

Some early leaders acted as intermediaries between their fellow ethnics and the larger adoptive society. Prominent among them was Charles C.A. Baldi Sr. (1862-1930), who arrived in Philadelphia from the province of Salerno in 1877, on the eve of mass immigration. He started as a lemon peddler and quickly became a sophisticated version of a padrone. He was not only a labor contractor, who recruited Italian workers for railroad companies, but also an interpreter for the Italian consulate, the operator of a small bank that sent remittances to Italy, a real estate owner who rented his properties to newcomers from Italy, and a political broker who brought out the Italian vote for the Republican Party after helping immigrants apply for U.S. citizenship and qualify for the suffrage. Moreover, Baldi served as president of numerous ethnic societies and owned L’Opinione, Philadelphia’s first Italian-language daily, which he founded in 1907. By the time he died in 1930 he had long been a member of the Board of Education and his sons had served both on the City Council and in the House of Pennsylvania’s General Assembly.

Baldi’s counterpart in Camden during the 1920s and 1930s was Tony Mecca (1873-1952), a former berry-picker turned undertaker who had settled in New Jersey in 1890. From his funeral home he assisted his countrymen in getting jobs and coping with American bureaucracy. Mecca, too, mobilized his fellow ethnics for the GOP in his capacity of president of the Italian Republican League.

Italian immigrants initially failed to shape a tight-knit ethnic community. The chief drawback of the belated achievement of Italy’s political unification was the lack of a national identity among Italians, who long retained a parochial sense of regional, provincial, or even local belonging. Newcomers from different places in their motherland, too, did not think of themselves as members of the same ethnic group and shied away from one another upon arrival in Philadelphia. Separated by disparate dialects, traditions, and even foodways, as well as by local antipathies, they gathered together along regional or provincial lines in self-segregated quarters within the broader Italian settlements. South Philadelphia’s so-called Little Italy was in fact a patchwork of regional neighborhoods. Chain migration based on family and township networks contributed to this phenomenon. Newcomers went to live with or near family members and fellow villagers who had preceded them to Philadelphia. Consequently, for example, Ellsworth Street became home to immigrants from the province of Catanzaro. Those from Abruzzi lived in the area around Eighth and Fitzwater Streets. People from the same towns in Italy sometimes resided even on the same blocks. This pattern was replicated elsewhere. For instance, an enclave of Sicilians from the fishing village of Sciacca settled in Norristown, while Chestnut Hill’s “Italian” quarter was in fact inhabited primarily by highly skilled workers in stone carving and tile setting from Friuli.

A Lack of Unification

Subnational segmentation extended to religious and social life. St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi had mainly northern parishioners of Ligurian, Tuscan, and Piedmontese ancestry, while southern Italians who felt unwelcome there went to mass at Our Lady of Good Counsel. The latter was the city’s second Italian Catholic church, established by Augustinian priests at Eighth and Christian Streets in 1898 after the immigrant tide from the South of Italy had gained momentum. Mutual-aid societies based membership strictly on local ancestry. For instance, only newcomers from Abruzzi and their progeny could join the Unione Abruzzese. Likewise, Chestnut Hill’s Venetian Club included solely immigrants from Friuli, and Norristown’s SS. Maria del Soccorso Society barred individuals from other-than-Sicilian background.

The development of an ethnic identity arising from the common national origin occurred in the decades between World Wars I and II. Due to the natural increase of the population, as of the 1930 U.S. Census Philadelphians of Italian birth or parentage totaled 182,368, about 9.3 percent of the city’s total residents. By that time most associations no longer required a particular geographical origin in Italy for membership. Moreover, the Order Sons of Italy in America, a nationwide fraternal organization that made a point of celebrating Italianness and had branches in several northeastern states, incorporated a number of Philadelphia’s preexisting clubs with regional and provincial denominations as its new lodges, stimulating their members to realize their mutual Italian roots.

The building of a more cohesive Italian community out of subnational colonies resulted from a few transformations that occurred in the years following the advent of World War I. As members of a U.S.-born second-generation with loose ties to their ancestral land came of age, they were not affected by their parents’ localistic divisions. Moreover, the end of mass immigration with the Quota Acts of 1921 and 1924 severely restricted the inflow of people from southern and eastern Europe by the mid-1920s. In addition, the Fascist regime enacted anti-emigration policies in 1927. Halting the flow of newcomers from Italy also put out the flames of subnational attachments. Jingoistic feelings following the outbreak of World War I and Italy’s aggressive foreign policy under fascism also encouraged the emergence of an Italian identity that replaced previous local allegiances. The U.S. appeasement of the Fascist regime, too, stimulated Italian immigrants to take pride in their national background. For instance, Republican Senator David A. Reed (1880-1953) of Pennsylvania overtly praised Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), and American opinion makers commended the assumed achievements of the Duce’s dictatorship for Italy’s modernization and the containment of communism.

Discrimination also induced Italian newcomers to close ranks across local divisions. Unlike their northern predecessors who had settled in Philadelphia before the 1880s, the turn-of-the-twentieth-century dark-skinned immigrants from southern Italy confronted xenophobia. Nativist sentiment branded them as violent and prone to crime due to their alleged Mafia connections.

With a reputed tendency to break strikes and accept substandard wages, people of Italian origin were considered unfair competitors on the job market and, at the same time, a potential source of corruption for bartering votes for money and political patronage. Moreover, they seemed inassimilable for their isolation in crowded, self-segregated ghettos and their limited English language. Italians also held a racial middle status between whites and blacks because of the alleged “African contamination” of their blood. Against this backdrop, Philadelphians from diverse regional backgrounds in Italy became more united as they endeavored to oppose the prejudice directed against them.

Immigration Curbed

Ethnic bias played a pivotal role in curbing Italian immigration to the United States before World War II temporarily halted the inflow of newcomers. The Italian tide resumed after the military conflict, although the federal legislation of the 1920s continued to restrain it significantly. In 1952 Philadelphians of Italian ancestry created a Committee for Better Government to lobby against immigration restriction based on the prospective newcomers’ national origin. Their efforts, however, were to no avail for thirteen years. Accordingly, the number of Italian-born residents in the city declined steadily and steeply, from 59,079 in 1940 to 9,279 in 1990. South Philadelphia’s population of Italian origin slumped almost 60 percent during the 1970s. Until this decade, the stagnant real estate values in the district and hostility toward prospective African American residents encouraged the stability of the community. Indeed, Italian Americans made a point of protecting their neighborhoods. They opposed public housing for blacks in Whitman Park and resisted school integration, in part by transferring their children to parochial schools. They also allied with Philadelphians of Polish and Irish descent to elect former police Commissioner Frank Rizzo (1920-91) to the mayoralty in 1971 and 1975 as a champion of the white backlash against African Americans’ alleged encroachment.

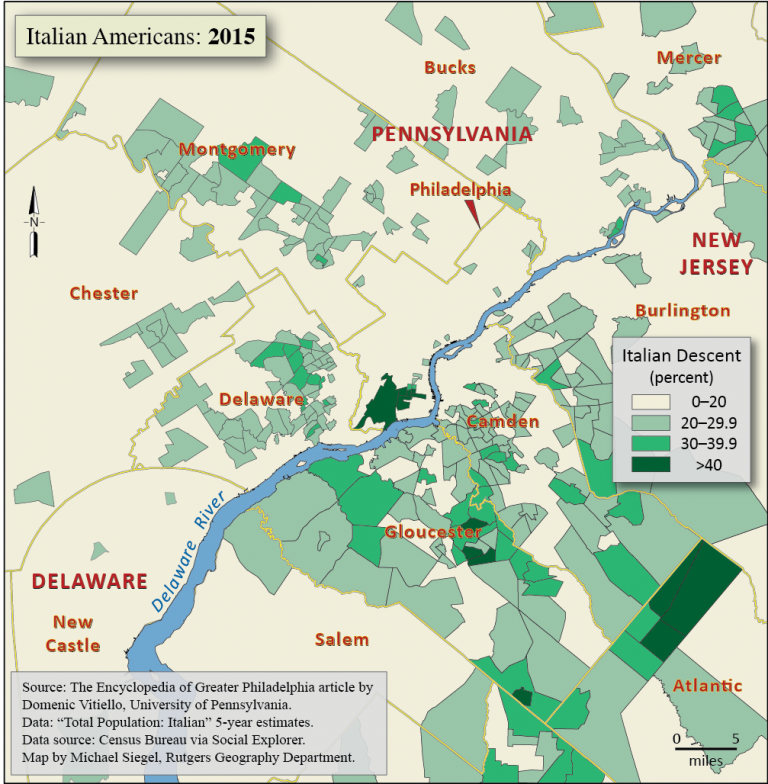

Although the federal Hart-Celler Act of 1965 (enforced beginning in 1968) repealed the national-origins system and reopened the door to more Italian immigrants, the inflow did not offset the death rate of the turn-of-the-twentieth-century generations of arrivals. Italy’s economic growth in the industrial sector between the late 1950s and the early 1960s curbed emigration because it enabled southerners to find employment in the country’s northern districts. At the same time, deindustrialization and job losses in Philadelphia, Camden, Norristown, and other manufacturing centers diminished the region’s attractiveness for prospective Italian newcomers. A decline in Camden’s Italian-American population resulted in the merger of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel and the predominantly Hispanic Our Lady of Fatima parishes in 1974. Likewise, in Philadelphia, St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi was combined with St. Paul in 2000.

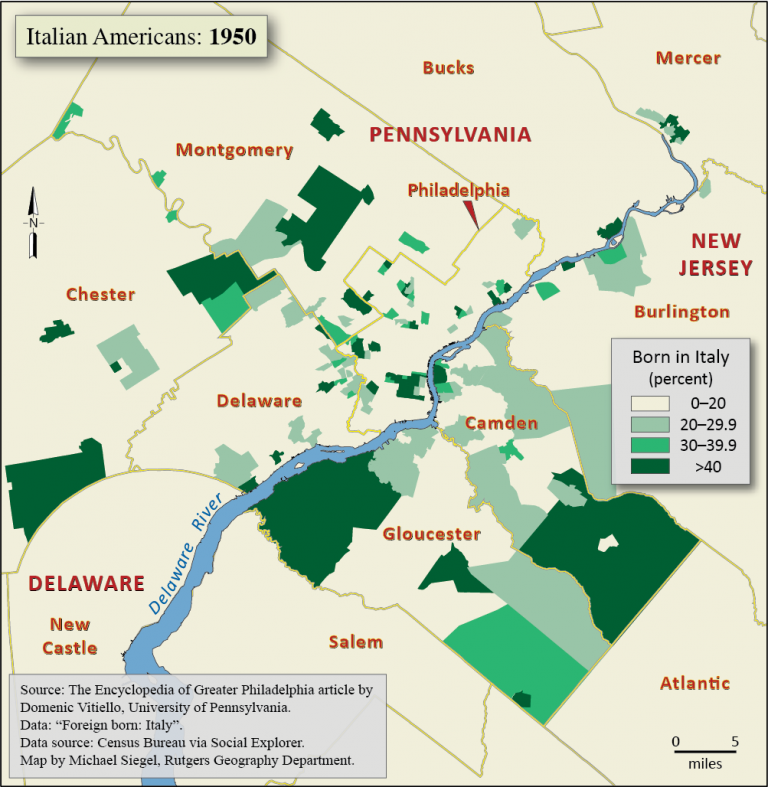

The few Italian expatriates tended to join relatives and friends who already lived in suburban districts. Indeed, while the number of Philadelphia’s Italian-born dwellers shrank in the postwar decades, suburbanization redrew the map of Italian-American population in the metropolitan region. As the prewar immigrants’ children and grandchildren entered the middle class, they moved to residential areas in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties as well as in southern New Jersey. There, they sometimes reproduced the ethnic enclaves they left in the city. In Ardmore, for instance, a population of Italian descent concentrated south of Lancaster Avenue.

Post-1968 immigrants were not only workers. The Italian presence in the 1980s also included cultural personalities such as conductor Riccardo Muti (b. 1941), who was the Philadelphia Orchestra’s music director from 1979 to 1992.

The late 1990s witnessed a new, albeit numerically small, immigration tide from Italy. These arrivals, who made up the bulk of Philadelphia’s recent Italian-born population, were mostly graduate students, young hyperskilled professionals, researchers, and academicians attracted by better education, higher quality of life, larger income, and more rewarding jobs than those available in their native land. Newcomers also escaped from a general sense of malaise resulting from flattened career trajectories, economic stagnation, and lack of perspectives for real changes and innovation in their mother country. As the perception of Italy’s economic, social, and political hopelessness deepened in the aftermath of the 2008 recession and during the subsequent slow and rough recovery, this wave of immigrants continued.

Stefano Luconi teaches History of the Americas at the University of Florence and specializes in Italian immigration to the United States, with special attention to Italian Americans’ transformation of ethnic identity. His publications include From Paesani to White Ethnics: The Italian Experience in Philadelphia (State University of New York Press, 2001) and The Italian-American Vote in Providence, Rhode Island, 1916-1948 (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004). He also edited, with Dennis Barone, Small Towns, Big Cities: The Urban Experience of Italian Americans (American Italian Historical Association, 2010). (Author information current at time of publication).

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- A change behind the scenes for iconic Italian Market stands (WHYY, December 24, 2013)

- Philly celebrates Italian culture — with more in store (WHYY, June 17, 2014)

- In the first language of our heart: Immigrants keeping the Catholic faith alive in Philadelphia (NewsWorks, September 17, 2015)

- A Day Without Immigrants leaves its mark on Philadelphia (WHYY,February 16, 2017)

Links

- Italian Immigrants in Pennsylvania (Lesson Plan, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Rural Roads, City Streets: Italians in Pennsylvania (Lesson Plan, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Ninth Street Market (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- America-Italy Society of Philadelphia

- What Sets Italian Americans Off From Other Immigrants? (National Endowment for the Humanities)

- States with the highest percentage of Italian Americans (National Italian American Foundation)

- NJ's Most Italian Town (New Jersey Monthly)

- Delaware Commission on Italian Heritage and Culture