Arboretums

Essay

The Philadelphia area is a recognized “hearth” of early American arboretums. Starting almost exclusively within a tight-knit community of Quaker botanists with a reverence for nature, early Philadelphia arboretums left a legacy of emphasis on native plants. Over time, the region’s arboretums also encompassed English naturalistic designs showcasing North American species and increasingly global perspectives, especially a focus on Asian and Japanese landscape design and plants.

Arboretums have much in common with botanical gardens, but are defined by their emphasis on woody plants, including trees, shrubs, and vines. Both botanic gardens and arboretums, however, are distinguished by an educational or scientific purpose along with aesthetic and recreational functions.

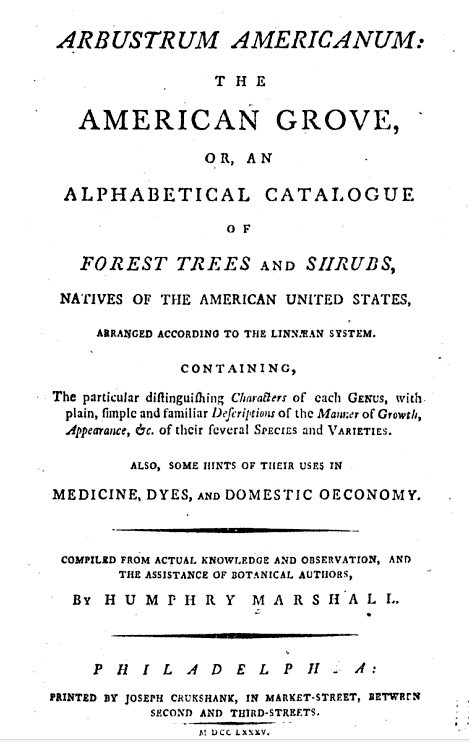

A complex network of Quaker botanists and dendrologists (those who study wooded plants) were at the heart of early arboretums in the Philadelphia area. In 1773, Humphry Marshall (1722-1801) established the first arboretum in the United States on his Marshallton, Pennsylvania, estate. A Quaker stonemason by trade, he was cousin to fellow Quaker John Bartram (1699-1777), founder of the first botanical garden in America. While Marshall’s arboretum showcased both native and European plants, his focus was on North American flora. In 1785, Marshall published Arbustrum Americanum, the first treatise on woody plants published in the United States. Some scholarship suggests this early and persistent Quaker affinity for native flora over transplanted exotics can be traced to religious beliefs about stewardship over God’s creation.

Quaker Arboretums, a Family Affair

A surprising number of these early Quaker arboretums were family affairs. In 1798, Quaker twins Joshua and Samuel Pierce began an arboretum known as Pierce Park. This arboretum was notable for how it epitomized early arboretums as scientific collections; the trees were laid out in straight rows by taxonomy. Humphry Marshall advised the brothers in their collecting. Some Pierce trees survived into the twentieth century at Longwood Gardens in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, through the intervention of Pierre S. du Pont, who purchased the property in 1906 to save it from timber companies. In 1825, two more Quaker brothers founded what would become the Tyler Arboretum: Jacob (b. 1814) and Minshall Painter (b. 1801). The two brothers, networking with Marshall, Bartram, and other Quaker dendrophiles, quickly gathered more than a thousand tree types. By the early twenty-first century the arboretum, the oldest extant arboretum on the East Coast, still held twenty original “Painter” trees, including the largest giant sequoia in Pennsylvania. In 1944, descendant Laura Tyler bequeathed Painter Arboretum to a board of directors and the property became the nonprofit Tyler Aboretum.

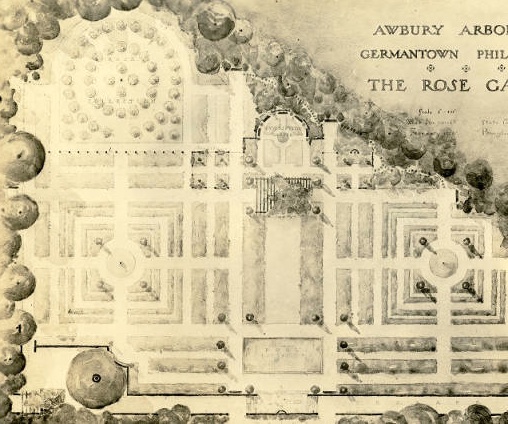

In the mid-nineteenth century, as the United States suffered anxiety over its cultural relationship with Europe, English garden designers became viewed as necessary to validate the aesthetic and scientific worth of an arboretum. No wonder, then, that the English gardener William Carvill was hired to design the (Quaker) Haverford College Arboretum in 1834. He incorporated sweeping vistas, while also expressing Quaker values of community and individuality within his English-style designs. The arboretum boasts a descendant of the American elm under which, by tradition, William Penn signed a treaty with the Native Americans. Likewise, the English-trained William Saunders (1822-1900) consulted on the master plans of Awbury Arboretum in the 1870s, before going on to design Gettysburg Cemetery and the Capitol grounds in Washington, D.C. Awbury also shared Quaker roots with Haverford’s arboretum; Quaker businessman Henry Cope, inspired by visiting the Woodlands estate in West Philadelphia, founded Awbury in 1852 in Germantown. After housing eight generations of Copes, Awbury became a formal public arboretum in 1916 and turned nonprofit in 1984.

Distinct from the Philadelphian lineage of Quaker botanists, another slightly later thread of arboriculture focused on international collections and global diversity. Closely following Humphry Marshall’s seminal publication on local fauna, William Hamilton (1749-1813) began planting trees at the Woodlands in 1786. Hamilton was an aristocratic Anglophile in his tastes and arboricultural practices. He introduced the Norway maple to North America, gave John Bartram a ginkgo sapling that became the oldest ginkgo on the continent, and voraciously collected globally diverse trees. He also shared a Quaker passion for North American plants, successfully petitioning for seeds from the Lewis and Clark expedition, although he displayed them in English naturalistic-style landscapes, with sweeping vistas punctuated by clusters of trees. In 1840, the Woodlands became a public cemetery to preserve his arboricultural legacy.

This non-Quaker strain of international dendrology was revived and brought to prominence in the 1876 Centennial Arboretum, still standing in Fairmount Park in the early twenty-first century. The Centennial Arboretum picked up where the international collector William Hamilton left off, showcasing trees from all over the globe, to much acclaim and imitation. Shofosu, the Japanese teahouse and garden at the Centennial Arboretum, influenced Western arboretum design and collections, arguably up to the addition of two Japanese gardens to Haverford College Arboretum in 1990 and 2004.

Barnes Foundation Arboretum

International collecting also became the focus of the Barnes Foundation Arboretum, initially developed by Captain Joseph Lapsley Wilson (1844-1928) beginning in 1880. Purchased by the Barnes Foundation in 1922, the arboretum boasts over 3,000 varieties of woody plants, including katsura trees, European beeches, Japanese raisin trees, and ginkgos. Also influenced by the Centennial Arboretum, in 1887 Quaker siblings John and Lydia Morris broke with the dominant Quaker precedent and began planting exotic trees. Their Compton estate grew in 1912 with the addition of “English Park,” made up almost exclusively of Chinese specimens, and a “Japanese Overlook” rock garden installed following the “Japanese Hill and Water Garden” addition of 1905. Known as Morris Arboretum since the University of Pennsylvania purchased it in 1932, the siblings’ estate became the official arboretum of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

More recent arboretums, informed by restoration ecology, have renewed emphases on native plants. The Jenkins Arboretum, founded in 1976 in Devon, took the southeastern Pennsylvania hardwood forest as its starting palette and specializes in eastern North American trees together with thousands of azaleas and rhododendrons. Similarly, the Lewis W. Barton Arboretum and Nature Preserve at Medford Leas, founded in 1981 in Medford, New Jersey, features New Jersey flood plain natives as well as global specimens. Tellingly, Medford Leas is a Quaker senior living community and receives guidance from the Quaker-founded Morris Arboretum. The Quaker strain of native gardening never died; even at the height of the exoticism craze in 1929, the Scott Arboretum of the Quaker Swarthmore College was designed to emphasize Eastern Pennsylvanian climate and ecology.

The roots of Greater Philadelphia’s arboretums run deep. In the region, arboretums display the influence of Quaker reverence toward nature, late nineteenth-century Anglophilia, Centennial celebrations of international collections, and an ever-growing focus on public education.

Anastasia Day is a Ph.D.-track fellow in the Hagley Program in the History of Industrialization at the University of Delaware. Her research interests include gender, consumption, technology, and environmental history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Wood artists salvage beauty from destruction at Bartram's Garden (WHYY, May 3, 2014)

- 'Home Tweet Home' exhibit at Morris Arboretum celebrates feathered friends (WHYY, June 3, 2014)

- Morris Arboretum birdhouses strictly for the people (WHYY, July 6, 2014)

- 'Meditative' outdoor art installation takes over Awbury Arboretum's grounds [photos] (WHYY, December 3, 2014)

- Winter's 'colorful gems' on display at Morris Arboretum (WHYY, March 5, 2015)

- Tyler Arboretum tries new management tool: Goats (WHYY, May 26, 2016)