France and the French

By Christina Virok and Lauren Cooper

Essay

Philadelphia’s long connection with France and the Francophone world took shape over several centuries. French settlers, visitors, expatriates, and refugees contributed significantly to Philadelphia’s early sociopolitical development. Over the years, Philadelphia received refugees from the French Revolution and French-speakers from the Caribbean and Africa who made lasting cultural contributions. Philadelphians celebrated Bastille Day, erected a monument to Saint Joan of Arc, adopted French styles in fashion, art, and architecture, and formed organizations to foster and advance Franco-American relations. As the city and the surrounding region grew and changed, the French connection remained.

French immigrants arrived in Philadelphia as early as the seventeenth century. Many French Protestants (Huguenots) left France after Louis XIV (1638–1715) issued the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau, which denied the legality of Protestantism and opened the door for mass violence and persecution against Protestant communities scattered throughout the kingdom. Some of those who fled Catholic-dominated France sought religious liberty in the tolerant Quaker colony of Pennsylvania. Most of these early French immigrants arrived as indentured servants and did not coalesce into a substantial ethnic community.

One of the most influential French Protestant arrivals was the educator and abolitionist Anthony Benezet (1713–84), whose family fled to England in 1715 in search of religious tolerance, and from there to Philadelphia in 1731. In his new city, Benezet embraced Quaker ideals of individual human value and universal humanitarianism. He embarked on a tireless mission of abolitionism, which linked Philadelphia to a network of prominent anti-slavery writers and activists on both sides of the Atlantic. At the Rising Sun Tavern at York Road and Germantown Avenue in 1775, Benezet called to order Pennsylvania’s first anti-slavery organization, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. Benezet also established America’s first school for girls in 1754 and a school for Black children in 1770. Through his experience with religious persecution, empathy for the oppressed, and humanitarianism, Benezet embodied the spectrum of influence of Frenchmen on the developing Quaker City.

Other early arrivals to the region formed trade networks between France and indigenous North American populations. Rising tensions in Europe prompted French privateers to raid British plantations and ships along the coast of Delaware’s New Castle County in the 1740s, leading Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) to propose a defense association funded in part by Philadelphia’s first lottery. As Pennsylvania merchants sponsored the westward expansion of British colonial trade, French fur traders and their allies—including the Lenni Lenape, native to the mid-Atlantic region—pushed back, eventually resulting in the Seven Years’ War (1754–63, also known as the French and Indian War). During the conflict, over 450 French settlers exiled by the British from the Canadian region known as Acadia arrived in Philadelphia as refugees. Many Philadelphians viewed the newcomers with suspicion, and largely quarantined them in “French Houses” at Sixth and Pine Streets. There, Ann Bryald established an informal French-language school and became the first known Catholic teacher in Philadelphia. Though many Acadian refugees received aid from wealthy French Huguenots, including Benezet, an outbreak of smallpox nearly halved the community by the mid-1760s, and subsequent emigration further diminished it.

The Revolutionary Era

Connections between Philadelphia and France intensified during the War for Independence from Britain (1776–83), when an alliance with France became critical for an American victory. As the meeting place of the Continental Congress, Philadelphia received several French diplomats who supported the young nation’s cause. France’s first envoy to the Congress, Julien-Alexandre Achard de Bonvouloir (1749–83), met clandestinely in Carpenters’ Hall with Benjamin Franklin and John Jay (1745–1829) to discuss French support for America’s cause. Francis Daymon, a French-born Philadelphian and secretary to the Congress, arranged the meetings, which readied the path for further Franco-American negotiations. In Paris as commissioner for the United States, Franklin helped to forge the alliance that produced the supplies, ammunition, and troops from France that became indispensable for the success of the American war effort.

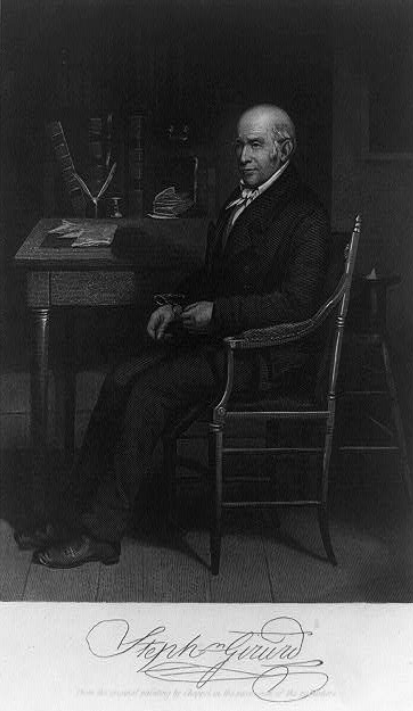

Trade as well as politics forged lasting links between France and Philadelphia. French native Stephen (Étienne) Girard (1750–1831), an accomplished sailor and merchant, spent ten years traversing the Atlantic from his native Bordeaux to the French colonies of St. Domingue (later Haiti) and Martinique. He arrived in Philadelphia early in the historic summer of 1776 after severe weather and the increased menace of a British trade blockade diverted his ship and its cargo from its probable destination in New York. Rather than return to France, Girard settled in Mount Holly, New Jersey, and opened a small business on Water Street, selling goods to Philadelphians suffering the consequences of the British blockade. Finding himself at the center of a revolution that spanned the Atlantic Ocean, Girard risked his life and business by sending ships through the blockades to procure supplies for American and allied troops. After the war, he continued his active role in the economic and civic affairs of his adopted city, connecting the port to the far reaches of the globe through trade. This trade empire, along with the labor of enslaved people of African descent working at his Louisiana plantation, made Girard one of the wealthiest men in the country.

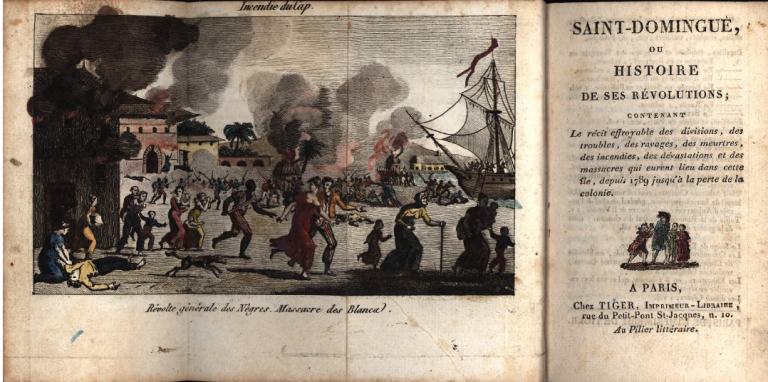

During the last decade of the eighteenth century, when Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital, the region’s French population ebbed and flowed with statesmen, émigrés, and refugees. The United States received approximately twenty-five thousand French exiles following the start of the French Revolution in the early 1790s, and three thousand refugees arrived in Philadelphia following the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). Of these, about 30 percent were enslaved people of African descent, who infused Catholicism and Francophone culture into Philadelphia’s free Black community. American-born Black Philadelphians successfully rallied against legislation intended to allow refugees to maintain ownership over the enslaved, although the majority of those emancipated were subsequently indentured to their former enslavers. In 1803, Benjamin Nones (1757–1826), a native of Bordeaux and veteran of Washington’s army, became the official interpreter of French in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Utilizing his leadership role in Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel synagogue, Nones encouraged Jewish refugees from St. Domingue to manumit the enslaved people they brought with them. From his office on Chestnut Street, he also aided Francophone newcomers in obtaining American citizenship.

City Tavern at Second and Walnut Streets became a common meeting place for the city’s growing French community, and a French business district developed in the blocks around it. Refugees received news about their friends and family across the Atlantic through newspapers like those produced in the book and printing shop of Martinique-native Médéric-Louise-Elie Moreau de Saint-Méry (1750–1819). When a yellow fever epidemic swept the city in 1793, French doctors from the Caribbean brought their medical knowledge of the tropical illness to the hospitals of Philadelphia. Among them was Dr. Jean Devèze (1753–1829), whose autopsy research disproved a widespread theory that refugees from St. Domingue had spread the fever.

A Role as Fringe Settlers

Frenchmen also played a modest role in developing the countryside in Pennsylvania and New Jersey as they settled on uncultivated lands and began small Francophone communities. In 1793, several influential Philadelphians, including Stephen Girard, purchased 1,600 acres of wilderness in present-day Bradford County, Pennsylvania. There, they built the short-lived town of French Azilum as a sanctuary for refugees from the violence of revolutionary France and St. Domingue. The swelling population of refugees also prompted Francophone settlements at Frenchtown (1794) in New Jersey and New Geneva (1795) in Fayette County, Pennsylvania.

In Philadelphia, French allegiances converged with controversies over foreign policy during the presidency of George Washington (1732–99). After Washington’s administration implemented the Jay Treaty with the British in 1795, merchants and members of the emerging Democratic Republican party protested that the Jay Treaty was an insult to France, which had been instrumental in procuring America’s independence just over a decade earlier. During the administration of John Adams (1735–1826), the series of naval conflicts between Britain and France known as the “Quasi War” (1798–1800) further strained Franco-American relations, leading to the passage of the 1798 Alien Friends Act, which targeted so-called radical French citizens for deportation.

The Philadelphia French community diminished by the onset of the nineteenth century as many refugees returned to their homeland once the political climate became less volatile. Between the 1820s and 1840s, several hundred English- and some French-speaking Philadelphians of African descent emigrated to Haiti. Although many later returned to Philadelphia, they continued to follow news from the newly emancipated country. The white descendants of permanent French immigrants to colonial and early Republican Philadelphia blended into the cosmopolitan city and did not retain a strong collective French identity.

Nineteenth-Century Impact

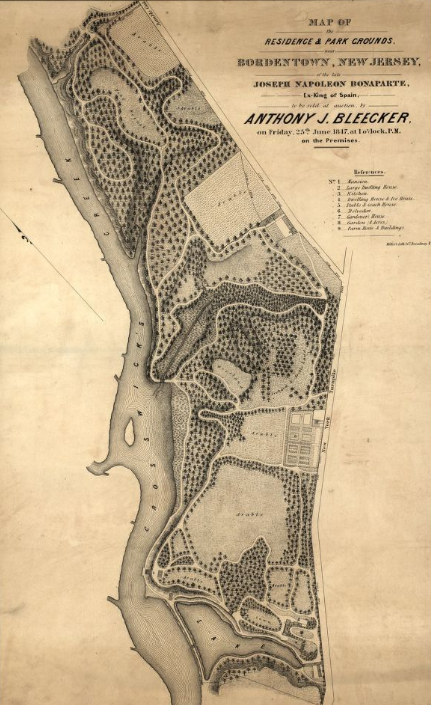

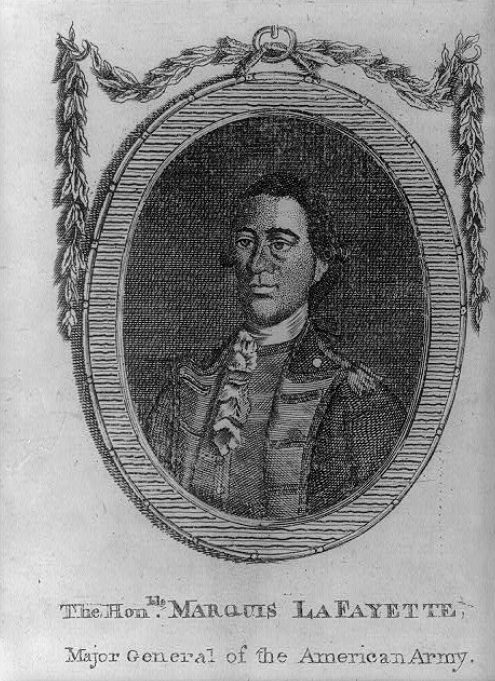

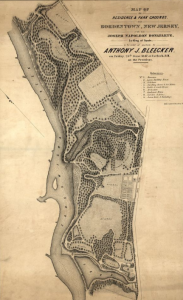

The dissolution of Napoléon Bonaparte’s (1769–1821) empire spurred another influx of French émigrés to the region. In 1815, Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844), the exiled king of Spain and Naples and elder brother of the recently defeated Emperor Napoléon, purchased a house at 260 S. Ninth Street in Philadelphia and later moved to Lansdowne, the former country home of John Penn (1729–95). A desire for greater privacy later led the former king to the environs of Philadelphia where he purchased Point Breeze, the former residence of American diplomat Stephen Sayre (1736–1818) in Bordentown, New Jersey. During the Bonaparte family’s stay from 1817 to 1839, the estate welcomed the elite of both Philadelphia and France, including the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834) in 1824.

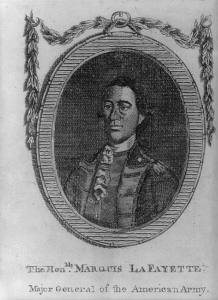

Lafayette, a French nobleman who came to Philadelphia as a young man to volunteer for service in the American Revolution, returned to the United States in 1824–25 to a hero’s welcome. During the war, he had camped with Washington at Valley Forge and led twenty-two hundred soldiers—including nearly fifty of the Oneida warriors he had recruited to the American cause—in the Battle of Barren Hill (1778). As Lafayette approached Philadelphia in 1824, six thousand uniformed volunteer militiamen greeted him with cannon blasts, and crowds of spectators carried banners featuring portraits of George Washington and Lafayette inscribed with the words, “To their wisdom and courage we owe the free practice of our industry.” French and Americans alike came out to show appreciation for the man who had fought alongside Washington and drafted the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789).

Soon after the visit of Lafayette directed Philadelphians’ attention to their history, the death of Stephen Girard in 1831 served to shape the city’s future. In a massive bequest to Philadelphia, the merchant funded the establishment of Girard College, which opened in 1848 as a school for poor, white fatherless boys (expanded later to admit girls and, through court action in 1968, any race). Girard also bestowed funds for the construction of Delaware Avenue, a wide thoroughfare along the city’s busy waterfront, to ensure the continued success of Philadelphia’s port.

As the region continued to develop, new industries emerged. In 1802, French refugee Éleuthère Irénée du Pont (1771–1834) had opened a gunpowder mill in Wilmington, Delaware. With the growth of mining and the outbreak of the Civil War (1861–65), E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Company expanded and became the largest supplier of gunpowder to the U.S. military. Other industrial enterprises founded by Frenchmen included Vineland Flint Glass Works, established by Victor Durand Jr. (1870–1931) in Vineland, New Jersey, in 1897.

Cultural Expressions

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, French culture maintained its presence in Philadelphia. Restaurants in the finer hotels featured French cuisine, and department stores imported French fashions. Black St. Dominguan caterers and craftsmen established business networks that tied together the small community of first- and second-generation refugees from Haiti. Following the 1804 declaration of Haitian independence, Black ministers began to deliver annual sermons of thanksgiving to commemorate the day, which coincided with the abolition of the American slave trade. On July Fourth of that year, French- and English-speaking Black Philadelphians gathered in Southwark to celebrate another kind of independence—independence from slavery. Annually, Philadelphians also commemorated the fall of the Bastille, the event that sparked the French Revolution. The celebrations included picnicking in city parks, wearing red, white, and blue badges, and singing La Marseillaise in support of the nation. For the 1889 centennial of the storming of the Bastille, the small French community in Philadelphia appealed to noted equestrian sculptor Emmanuel Frémiet (1824–1910) to cast a monument to one of France’s national figures, Saint Joan of Arc (1412–31). Frémiet’s statue stood at the east end of the Girard Avenue Bridge from the time of its dedication on November 15, 1890, until 1948, when it was moved to a more prominent location near the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Many civic buildings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries reflected trends in French architecture, such as the French Second Empire style, which characterized the Louvre in Paris. Philadelphia’s City Hall (designed prior to 1871) became one of the best examples of the style in the United States, and Second Empire features could also be found on mansions and row houses around the region. The Beaux-Arts style, developed in Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts, also featured prominently in Philadelphia public spaces, including Memorial Hall (completed in 1876 for the Centennial Exhibition) and the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (designed in 1896). In an era when many European nations outside of France gravitated away from Beaux-Arts, American architects embraced the style, which gained its grandest local expression with the construction of the Fairmount Parkway (later renamed for Benjamin Franklin, built beginning in 1917). An attempt to renew the urban landscape and ease heavy congestion in Center City, French-born architects Jacques Gréber (1882–1962) and Paul Cret (1876–1945) intended the thoroughfare to emulate Paris’ famous boulevard, the Champs-Elysées. Lining the Parkway are other Beaux-Arts buildings, including the Parkway Central Library (1927) and Philadelphia Museum of Art (1928)—both designed in part by African American architect Julian Abele (1881–1950)—and the Rodin Museum (1929)—designed by Cret—which featured one of the world’s most comprehensive public collections of work by French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917).

French Impressionism captivated the enthusiasm of artists and collectors in the Delaware Valley for more than a century. In 1866, Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), left her studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and moved to Paris, where she continued her artistic training and eventually exhibited with the Impressionists. The style also crossed the Atlantic with artists like John Fulton Folinsbee (1892–1972), who studied in France and then settled in Bucks County, where Impressionism found an American expression with the flourishing of the New Hope School. A great supporter of the artistic movement, Albert Barnes (1872–1951), a chemist and businessman, amassed one of the world’s largest collections of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. In 1922, he established the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania, making his collection a centerpiece for art education. A new showcase for the collection opened on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 2012.

The First and Second World Wars reinforced historic connections between France and the United States. On May 9, 1917, shortly after the United States entered the First World War, a commission of French dignitaries arrived in Philadelphia. Like Lafayette almost a century earlier, these representatives of the French war effort received a heroes’ welcome from more than 100,000 spectators hoping to show their solidarity with France. In addition to soldiers and medical personnel, over six hundred Quaker pacifists deployed to France during the war to build housing for displaced persons under the auspices of the newly formed, Philadelphia-based American Friends Service Committee. Demonstrations of Philadelphia’s affiliation with France continued when war in Europe stirred again. With news of France’s defeat by German forces in 1940, Philadelphia’s annual Bastille Day ceremony took on a somber tone as the Consul of France placed a wreath at the foot of the statue of Joan of Arc. A wistful sonnet written by Pierre Giroud (c. 1856–?), a former professor of French at the University of Pennsylvania, invoked the saint as the community’s rallying point and protector of their homeland.

Contemporary Connections

The Philadelphia region gained new French-speaking populations in the twentieth century as the colonial empire of France crumbled. Haitian migration to the United States resumed in the twentieth century in three waves: during the American occupation of the island from 1915 to 1934, during the regimes of François Duvalier (1907–1971) and Jean-Claude Duvalier (1951–2014) from 1957 to 1986, and after the coup d’état of Jean-Bertrand Aristide (b. 1953) in the 1990s. Philadelphia became a growing destination for Haitians seeking more affordable living conditions. By 2015, the U.S. Census recorded approximately thirteen thousand Haitian immigrants living in the Greater Philadelphia region, primarily centered in three districts: the Olney-Oak Lane section, the Near Northeast, and West Philadelphia. Organizations like the Haitian Professionals of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Haitian American Chamber of Commerce facilitated cultural programming and offer assistance for new immigrants and developing businesses in these communities. Haitians also settled in Upper Darby, Delaware County, and throughout New Jersey, where growing communities in Trenton and Willingboro continued to receive new immigrants and refugees—many of whom were granted Temporary Protective Status following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Immigrants also came from former French colonies in Southeast Asia and West Africa. Refugees from the Vietnam War in the 1970s settled primarily in South, West, and Upper North Philadelphia. Philadelphia’s first Vietnamese retail plaza, established in 1990, helped to make South Philadelphia’s Washington Avenue a commercial center, and associations such as Huong Vuong emerged to serve the growing community. In the first decades of the twenty-first century, Francophone migrants and refugees from Senegal, Guinea, and the Ivory Coast joined a community of West African immigrants living and working in Southwest Philadelphia’s “Little Africa,” home to a thriving restaurant district.

Organizations formed during the twentieth century joined established institutions like the French Benevolent Society (1793) in fostering and advancing Franco-American relations. Philadelphia’s chapter of the Alliance Française, dedicated to promoting French language and culture, held its first meeting at the Acorn Club at Fifteenth and Locust Streets on March 9, 1903. The language classes grew into a school, opened in the 1970s, and the group now sponsors a variety of recreational activities. The French International School of Philadelphia, (École Française Internationale de Philadelphie), located in Bala Cynwyd in Lower Merion Township, opened in 1991 to serve the region’s rising French expatriate population. By 2014, the school enrolled 320 French, American, and international students. The nonprofit association Philadelphie Accueil formed in November 2000 to welcome and provide information to French speakers new to the Philadelphia region.

On the economic front, Philadelphia gained a chapter of the French-American Chamber of Commerce (FACC), established in 1989 as part of the bi-national nonprofit organization. In 1991, forty-seven French companies operated in the mid-Atlantic region; that number continued to grow as French corporations sought out greater Philadelphia’s central location between New York and Washington, D.C. The largest employers included Saint-Gobain, a manufacturing company headquartered in Malvern, Pennsylvania, and Air Liquide, a supplier of industrial gasses headquartered in Newark, Delaware. In partnership with the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians and the Chambers of Commerce and Industry in France, in 2014 the FACC-Philadelphia began a business development program that assisted fifteen French enterprises and entrepreneurs in entering into the American market in its first four years. In 2018, French companies employed over seventy-five thousand people in the tri-state area, and France was the largest foreign employer in New Jersey.

French ties to the region were strengthened by the passage of a Partnership City agreement between Philadelphia and Aix-en-Provence in 1999. With the goal of forging lasting economic ties and cultural understanding, Citizen Diplomacy International coordinated exchange trips for students, business leaders, and cultural institutions in the two cities. During a 2014 trip to France to promote Philadelphia as a center for tourism and industry, Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) visited the headquarters of Paris’s bike share program to learn best practices prior to the 2015 launch of the Indego bike share program in Philadelphia.

From venues for French cooking near Rittenhouse Square—promoted as the “French Quarter”—to cultural showcases at museums around the region, Francophone culture continued to appeal to Philadelphians and draw visitors to the region. From the time of its founding, Philadelphia maintained a trans-Atlantic dialogue with France through commerce in goods, and more importantly in ideas that shaped the character of both nations. Ideas concerning the promotion of abolitionism and universal human liberties were shaped through exchanges between French and American scholars, business owners, and philanthropists. French architecture and art transformed Philadelphia’s urban and cultural landscape. The enthusiasm of Philadelphians for French culture fluctuated with the tides of international political change, but France’s mark on the city remained.

Christina Virok is a Foreign Language educator in the greater Philadelphia area and earned her master’s degree in history at Villanova University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Lauren Cooper is the Interpretive Planner at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. She completed a master’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania, and has worked at cultural institutions throughout Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Philadelphia Orchestra pop-up quartet in Lyon, France (video) (WHYY, June 1, 2015)

- Amid French shock and mourning, Philadelphia’s Bastille Day celebrates ‘power to the people’ (WHYY, July 17, 2016)

- Meet the artist who’s recreating a classic French painting — West Philly style (WHYY, August 18, 2020)

- Twitter Email ‘It’s more than memories – it’s France’; French expats in Philly wonder if Notre Dame will be restored (WHYY, April 16, 2019)