French Revolution

By David Reader

Essay

The French Revolution of 1789 created political, social, and financial instability throughout Europe, prompting many terrified French aristocrats, businessmen, and intellectuals to flee to the United States. Philadelphia, with its cosmopolitan atmosphere, accessible port, and thriving commerce, attracted many of the French émigrés. Most settled along the Delaware River in the Mulberry district of Philadelphia (an area between modern day Market Street, Arch Street, Second Street, and Columbus Boulevard). Others spread over the region, across the Delaware into New Jersey, and across the Brandywine into Delaware.

The French Revolution’s declared ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity immediately appealed to Philadelphians in view of their own revolution. During the 1790s, as Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital, parades and celebrations welcomed French naval vessels and dignitaries, and many Philadelphians showed their support by singing the Marseillaise, wearing liberty caps, and commemorating Bastille Day. The emerging salon culture of Philadelphia gained greater legitimacy with the arrival of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord (1754-1838) in 1794. His reputation as a statesman and thinker contributed to the increasing intellectual influence of French émigrés on Philadelphia’s publishing houses, newspapers, schools and academic societies.

French émigrés established political societies and charitable organizations of their own. The Société Française de Bienfaisance de Philadelphie helped newly arriving French émigrés adjust to life in the city. During the yellow fever epidemic of 1793, emigré physicians with the help of Stephen Girard (1750-1831), a wealthy French émigré who arrived in 1776, remained in Philadelphia at Bush Hill Hospital to administer to the sick. Their dedication and contributions to medicine challenged the prevailing understanding of fighting disease in Philadelphia. Nevertheless, the highly selective American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia admitted few French émigrés for their contributions in science, philosophy, and other academic fields.

The Francophile atmosphere of Philadelphia delighted Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), who shared the positive outlook on the new republicanism of France. But President George Washington (1732-99) and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) were hesitant to support the French Revolution. Jefferson and Hamilton were at constant loggerheads over domestic and foreign policy issues. Philadelphia’s thriving newspaper industry exploited the division within the Washington administration. Philip Freneau’s (1752-1832) National Gazette and Benjamin Franklin Bache’s (1769-98) Aurora supported French republicanism while John Fenno’s (1751-1798) Gazette of the United States reinforced the views of the Federalists.

Crowd Welcomes French Minister

In 1793, Philadelphia welcomed French Minister Edmond-Charles Genet (1763-1834) with residents and émigrés lining the streets from Grays Ferry to the City Tavern. Citizen Genet’s mission was to rally support for the war developing between Great Britain and France. The conflict had weakened trade and threatened to pull the United States into a European war. President Washington had issued a proclamation to maintain a policy of neutrality, placing a priority on avoiding entanglement in the European war despite U.S. treaty obligations to France that were negotiated during the American Revolution. (Citizen Genet’s controversial decisions and the changing political landscape in France led to his removal in 1794, but divisions over U.S. relations with France continued.)

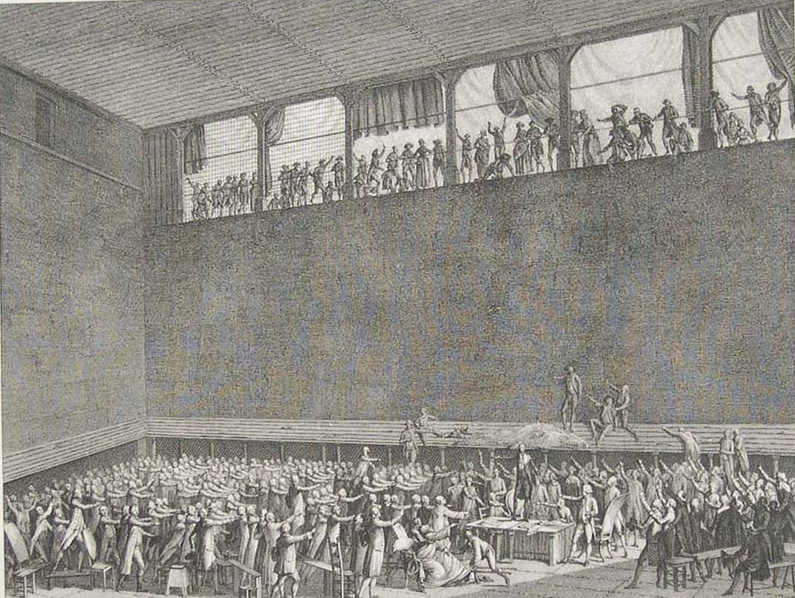

The Reign of Terror, a period of radical republicanism in France from 1793 to 1794, alienated Philadelphians who were repulsed by the executions of King Louis XVI (1754-93) and his wife Marie Antoinette (1755-93). They feared that the excesses of the French Revolution were infecting Americans in their chants for democracy and distrust of Federalists. Nevertheless, many Philadelphians flocked to guillotine demonstrations, dressed in the French fashion of the sans-culottes, and attended celebrations dedicated to Reason.

When the Reign of Terror ended, many of the French émigrés returned home. The political influence of the French émigré community in Philadelphia began to decline with the election of John Adams (1735-1826) to the presidency in 1796 and the break in Franco-American relations that came with the wars of the French Revolution during the late 1790s, but the cultural legacy of the French remained in the arts and sciences. At the same time, a residual, but profound, effect of the French Revolution was its part in stirring rebellion in the French colony of St. Dominque (later Haiti), which led to a slave revolt that overturned French power there, caused the flight of Francophone slaveholders and others to Philadelphia and other American seaport cities, and invigorated local Afro-Caribbean culture in the region.

David Reader teaches history at Camden Catholic High School and as an adjunct at Saint Joseph’s University. He was the recipient of the James Madison Memorial Fellowship in 2007. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History