Valley Forge

Essay

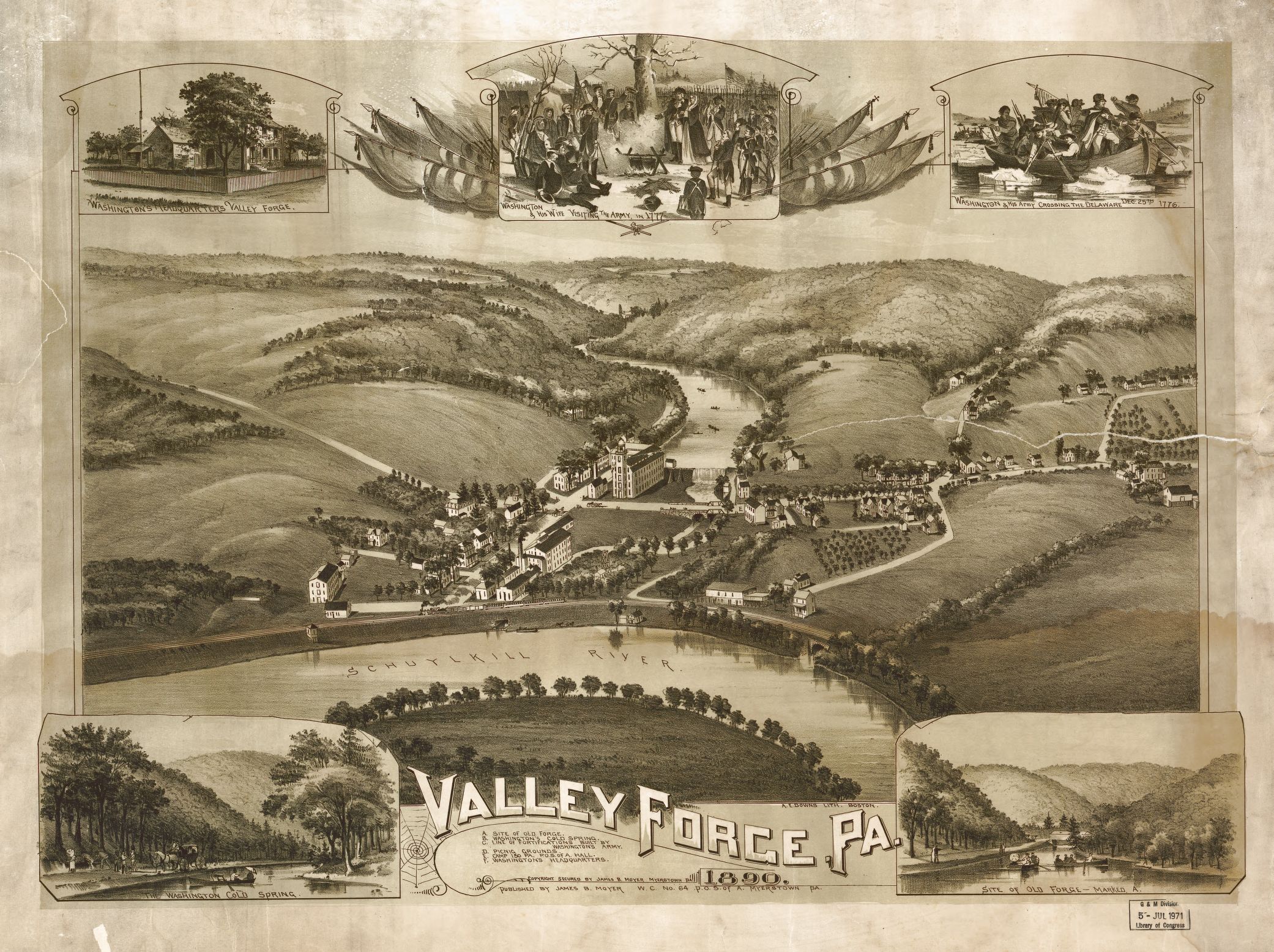

In 1777 the Continental Army, unable to prevent the British forces from taking Philadelphia, retreated to Valley Forge for the winter of 1777-78. Selected for its strategic location between Philadelphia and York, along the Schuylkill River, Valley Forge had natural defensive positions, access to water, enough land to support the army, and was far enough from Philadelphia to prevent a surprise attack by the British. While preserved for its eighteenth-century significance as the 1777-78 winter encampment of the Continental Army during the American Revolution, Valley Forge has a more extensive past and continues to play an integral role in the region’s history and environment.

American Indian tribes inhabited the area that became known as Valley Forge as early as the Archaic Period, 8000 BCE to 1000 BCE. William Penn’s land grant in 1681 led to plantations, which displaced the Indians. In 1699, the Pennsylvania Land Company of London bought the land that later became the north side of Valley Forge National Historical Park; the majority of it was subsequently purchased by two families, the Pawlings and the Morgans. By the early 1700s they had established substantial plantations called Pawlings and Mill Grove.

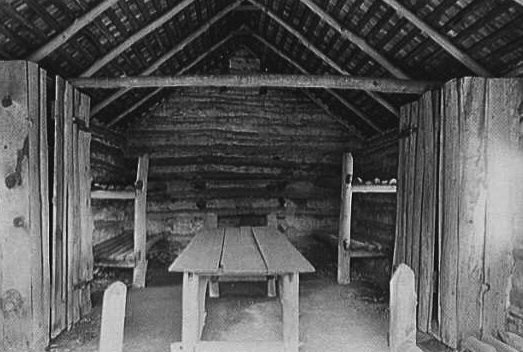

At the start of the American Revolution Valley Forge was one of several farming towns that supplied Philadelphia. Along with large farms, the town also included several mills, a forge, and a predominantly Quaker population. The revolution came to Valley Forge in December 1777, after British troops moved south from New York and captured Philadelphia, and the Continental Army retreated. At Valley Forge, generals and their staffs rented homes of local farmers, most of who stayed to care for their livestock and safeguard their property. Soldiers initially lived in tents, but for this long-term encampment they also constructed log cabins, sixteen by fourteen feet in size, each housing sixteen men. The soldiers suffered from lack of basic supplies due to mismanagement and weather conditions. Contrary to popular belief, Valley Forge was not the coldest encampment of the War for Independence (Morristown, New Jersey, was). Mild weather with heavy rain resulted in muddy roads and swollen rivers that prevented supplies from reaching the camp.

During this encampment the newly appointed Prussian-born Inspector General Baron von Steuben (1730-1794) began drilling the Continental Army. The Battle of Monmouth Courthouse (1778), while not a victory for the Americans, proved that the new skills learned under the general were essential to the army’s survival.

Remnants of Military Occupation

During the Revolutionary War the farms at Valley Forge were ransacked by the British troops and used by the Americans. Archaeologists have uncovered saw-cut animal bones from cattle and pigs, uniform buttons, musket balls, and redware shards from the Revolutionary period to verify these events. Following the war the land continued to be farmed, and the community embraced scientific farming. The first permanent bridge over the Schuylkill was built in 1810, and the canals came into place during the 1820s.

Initial preservation efforts at Valley Forge did not start until the mid-nineteenth century, when poets began romanticizing the site and it became a place of interest for the colonial revival movement. By the 1880s, trains brought tourists from Philadelphia to Valley Forge.

The Centennial and Memorial Association, modeled after the Mt. Vernon Ladies Association, set about opening Washington’s Headquarters as a historic house museum for the encampment’s centennial. The fundraising efforts were spearheaded by Anna Morris Holstein (1825-1900) and initially were very successful. The first “march out” commemoration of the end of the encampment was held on June 19, 1878. With the aid of the Patriotic Order of the Sons of America (POSA) and a grant from the state, the restored house was eventually purchased from private owners (the house had been privately owned and lived in since 1778) and opened to the public.

From Encampment to State Park

In 1893 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania took a further interest in Valley Forge and established it as a state park. The state park commission began acquiring land that encompassed remnants of the inner and outer line defenses from the encampment and eventually accrued several historic structures, including Washington’s Headquarters, as well as a thin strip of property north of the Schuylkill River.

The area remained popular into the 1920s with city dwellers seeking to escape the oppressive heat of the city and return to nature. The south side of the park remained a historic tourist destination, but the popularity of the north side declined. With the strong connection to the American Revolution, Valley Forge became a symbolic site for reflection, commemoration, and occasionally protest. During the Vietnam era, Vietnam Veterans Against the War organized Operation RAW (Rapid American Withdrawal), a march from Morristown to Valley Forge culminating with a rally in Valley Forge on Labor Day 1970.

In 1976 the National Park Service acquired stewardship of Valley Forge when President Gerald Ford (1913-2006) signed legislation creating Valley Forge National Historical Park. Today, Valley Forge National Historical Park is more than five square miles of green landscape in Philadelphia’s suburban sprawl. Bisected by the Schuylkill River, the park is divided into the well-known south side, where there is an abundance of historic structures and interpretation of the Revolutionary War, and the north side, which has an extensive trail system.

Siobhan Fitzpatrick has worked with several history organizations in New Jersey and at Valley Forge National Historical Park. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University.