Seven Years’ War

Essay

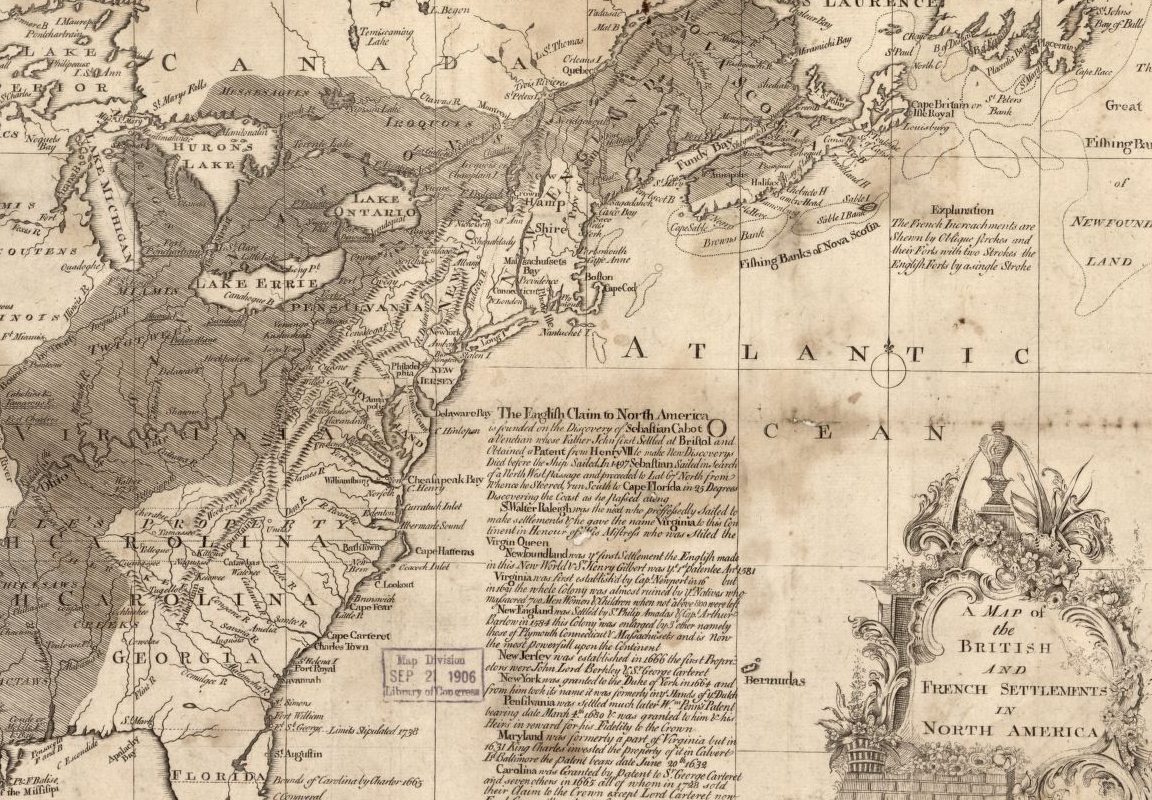

Philadelphia and the surrounding area played a significant role in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), also known as the French and Indian War and the Great War for Empire. Beginning in North America and spreading to Europe, India, and the West Indies, the war was a struggle for colonial dominance between France and Great Britain that grew to include all major and many of the lesser powers in Europe. As the most significant port on the east coast, Philadelphia and the surrounding region, including New Jersey, were drawn into the conflict. The war accelerated the region’s transition from a town and hinterland into a major urban area as Philadelphia became a haven for refugees and a staging area for troops and supplies. The war also transformed the region’s economy and politics as Quaker power diminished and the electoral base broadened with the addition of many who benefited from the wartime economy and qualified for the franchise.

In 1754, Pennsylvania possessed no standard organization for colonial defense. While independent military organizations, known as the Associators, had existed since King George’s War (1744-48), a more-uniform institution would be required to meet the needs of the growing conflict. Awareness of these needs helped Pennsylvania Assemblyman Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) garner support for passage of the first militia law in Pennsylvania in 1755. Following the pattern of similar laws in the New England colonies, the law permitted the men who volunteered the right to choose their own officers. Such a democratic approach was opposed by Governor Robert Hunter Morris (1700-64), who stood in league with the Proprietary interest of the colony and prompted passage of a second version of the law. As a result, two competing militia organizations existed in the colony for a brief time. The Associators remained the principal defensive force of the city, while the militia served as the first line of frontier defense.

New Jersey raised troops for colonial defense as well. Since the colony’s borders were not threatened with invasion, its troops were sent to the New York frontier to aid in the defense of that colony. Much of the New Jersey regiment was taken prisoner at the siege of Oswego in 1756.

Quakers, Pacifism, Defense

From the outset of the war, significant division existed among Pennsylvania Quakers as to whether they should take any role in the defense of the colony. Some Quaker leaders objected that taking any role in the defense of the colony would violate their vows as pacifists. Others who viewed support for defense as within the Quaker mission of spreading peace may have been influenced by calls for aid from beleaguered frontier communities beset by Indian raids. Most Quakers serving in the Pennsylvania Assembly supported appropriating money for defense purposes between the fall of 1755 and summer of 1756. As it became clear that the conflict would last longer than initially anticipated, some grew more reticent to vote money for military measures. Six Quakers resigned from the Assembly, an action that provided opposition groups an opportunity to dislodge the Quaker majority in the fall 1756 elections.

In addition to raising troops, Philadelphia served as a military staging area. In late 1756, the British commander, John Campbell, Lord Loudon (1705-82), dispatched the Sixtieth, or Royal American, Regiment to the city. At the time, Philadelphia did not possess any barracks to house them, which touched off a major controversy. Numerous inn and tavern keepers refused to take the British soldiers at the rates then being offered by the Crown. The commander of the Royal Americans, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bouquet (1719-65), sought to make an arrangement with the mayor of the city, but to no avail. On receiving word of the situation, the commander of British forces in North America, Lord Loudon, threatened to use force to acquire shelter for these troops, who were suffering from the effects of exposure to the weather and an outbreak of smallpox. At this point, a committee led by Benjamin Franklin succeeded in getting the tavern owners and innkeepers to accept the prescribed rates, ending the controversy.

Philadelphia also served as the staging area for the successful campaign led by Brigadier General John Forbes (1707-59) against Fort Duquesne in 1758. On his return, Forbes died in the city and was interred in the cemetery at Christ Church.

The War’s Drag on Commerce

The industries and port of Philadelphia, the major trading and ship-building center in North America, were significant in supplying the needs of the British forces in North America. The city supplied British troops with everything from candles to fresh provisions. But the war interfered with commerce as well. Before the outbreak of hostilities, ships from the Philadelphia area traded up and down the eastern seaboard as well as internationally. Part of this trade had always been illegal, and during the conflict, the Pennsylvania colonial authorities made greater efforts to suppress the illicit trade with the French through the neutral ports of the West Indies.

The conflict significantly altered the social make-up of Philadelphia. Refugees poured into the city from western Pennsylvania because they feared Indian attacks. In addition, roughly 450 Acadians who were forced out of their homes in Nova Scotia because the English feared they would be loyal to the French settled in Philadelphia in a row of one-story wooden structures on Pine Street. Both groups became dependent on the protection and philanthropic support of the city’s Quaker population.

As the transformation of Philadelphia and the surrounding area from a colonial town into a city accelerated during the Seven Years’ War, the conflict significantly altered the political makeup of the city. The power of the Proprietary Party continued to diminish, and the working classes began to feel their political power as they had been mobilized in groups such as the Philadelphia Associators. The Seven Years’ War also touched off the subsequent Pontiac’s War (1763-66), which caused additional upheaval on the western Pennsylvania frontier. The panic caused in 1764 when angry frontiersmen known as the Paxton Boys marched toward Philadelphia further eroded the political influence of the Quakers, who became increasingly associated with strict pacifism. Opponents accused the Quaker leadership not only of failing to protect the colonists during Pontiac’s War, but also of aiding Indians. The controversy led some rising political figures such as Benjamin Franklin to call for Pennsylvania to dispose of the Proprietors and become a Royal colony. The resulting political awareness among groups outside of the Quaker-dominated Proprietary interest would become a power force in the protests against British tax policy leading to the American Revolution.

James R. McIntyre is an Assistant Professor of History at Moraine Valley Community College, Palos Hills, Illinois. He serves as the editor of The Journal of the Seven Years’ War Association. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University