Native and Colonial Go-Betweens

Essay

During the colonial period, the diversity of the region that became southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and northern Delaware made trade and diplomacy difficult. The many cultural, especially linguistic, barriers between various Native American and European groups required go-betweens, or intermediaries. The intermediaries who were called upon to interpret across cultures and help maintain the fragile peace were as diverse as the region from which they came. They included, among others, a Swedish fur trader, an English-speaking Susquehannock, an Unami-speaking Quaker, an Onyota’a:ka (Oneida) living in a multi-ethnic town, a German farmer, a French-Onyota’a:ka-Algonkin guide, and a Prussian Moravian missionary.

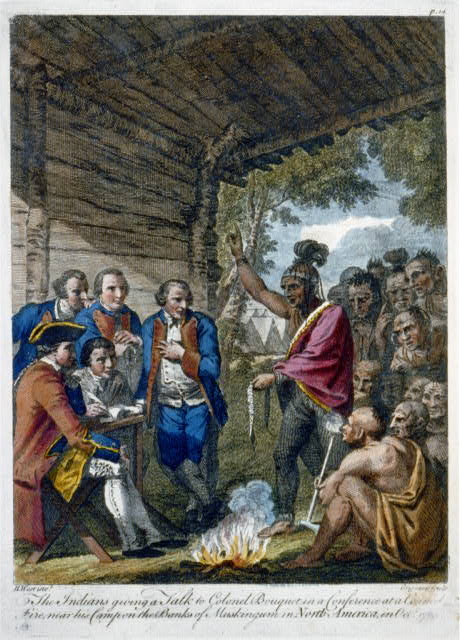

Trying to maintain peace from the early seventeenth century to 1763 was demanding work. Intermediaries spent much time on the road carrying letters and wampum belts across treacherous terrain. Once they reached their destination, they translated the letters and belts as well as swapped and gathered information. At the great councils, which followed Native American customs, intermediaries translated the speeches given by Indigenous and colonial leaders. Following Indigenous protocols enabled Native American leaders to select go-betweens based on kinship connections and their standing within the community, while colonial leaders had to identify individuals with an intimate knowledge of a particular Indigenous culture and language, which were extremely difficult to learn.

The earliest colonial intermediaries in the region were Dutch fur traders. Two of the first were Simon Root, who lived in a home at Wigquakoing (now Wicacoa in South Philadelphia), and Jan Andriessen, who lived near Fort Casimir (present-day New Castle, Delaware). On July 13, 1647, for example, Root and Andriessen, who claimed to understand the Susquehannock language, testified to New Netherland director-general Petrus Stuyvesant (c. 1592-1672) that Aquariochquo and Quadickho, two Susquehannock leaders, wanted to continue mutual trade with the Dutch even though New Sweden governor Johan Printz (1592–1663) had asked for permission to set up a trading post among them. Printz claimed that he, not the impoverished Dutch, could sell them plenty of powder, lead, and guns.

The Growth of Intermediaries

Root and Andriessen were soon joined by a number of other Dutch and Swedish intermediaries, including Jacob Svensson who acted as a go-between for the Swedes and Dutch with the Susquehannocks and Lunaapeew (Lenapes). However, the most important intermediary in the second half of the seventeenth century was one of Root’s neighbors, the Swedish fur trader Lars Petersson Cock (d. 1699). Prior to the arrival in 1682 of the new proprietor of Pennsylvania, William Penn (1644-1718), Cock arranged, in his own home, land sales between Lunaapeew leaders and the proprietor’s representatives.

When Cock died in 1699, finding a replacement proved to be quite difficult. Although Pennsylvania officials employed a number of Native American go-betweens, including a Conoy named Ouseywayteichks who reportedly knew four Indigenous languages, and the English-speaking Susquehannock Shawydoohungh, provincial officials were loath to rely solely on Indians no matter how effective they might be. Thus, officials also turned to French fur traders such as the Huguenot Jacques Le Tort (c. 1651-c. 1702) and his son James Le Tort (c. 1675-c. 1742), who married a Shawnee woman; the brothers Pierre Bizaillon (1662–1742) and Michel Bizaillon; and Martin Chartier (1655–1718), who married a Shawnee woman named Sewatha Straight Tail (b. 1660). Provincial leaders also relied on the Quaker fur traders John Cartlidge (1684-c. 1723) and Edmond Cartlidge (1689-1740) who spoke Unami, the language of the Lunaapeew groups who occupied the southern part of Lenapehoking, which included present-day southern New Jersey and a small portion of eastern Pennsylvania and northeastern Delaware. By 1722 Native American and colonial leaders had plenty of intermediaries to call on when trade and land crises arose.

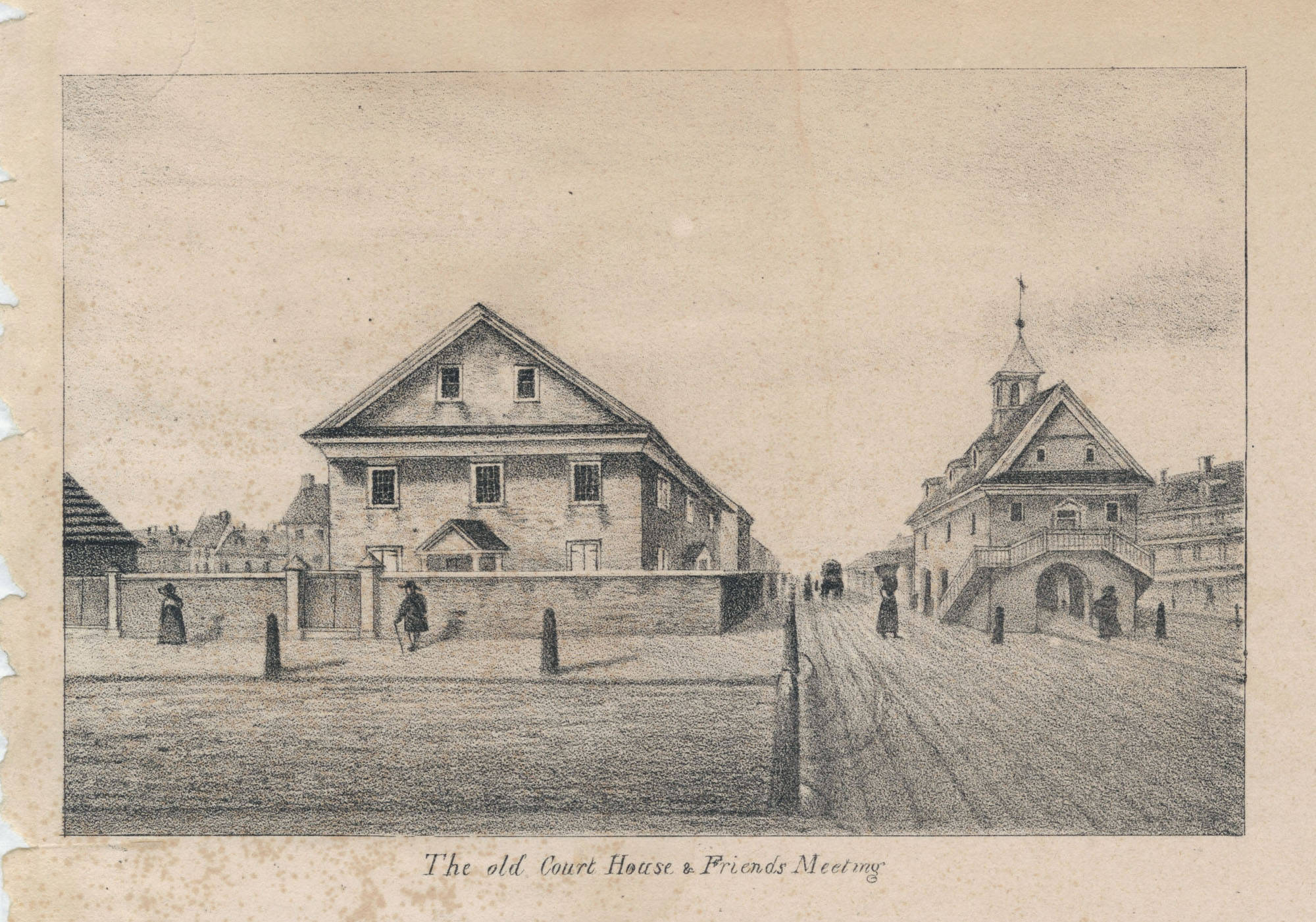

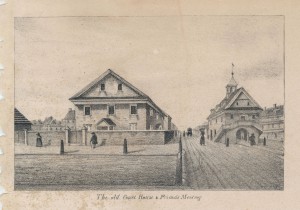

In 1728 rumors of war swept across the region. The Lunaapeew proposed war against the European settlers while Susquehannocks threatened war against the Shawnees. Meanwhile, a skirmish between eleven Shawnees and twenty colonists in the Tool-pay hanna (Schuylkill River) valley led to the murder of three Lunaapeew. Governor Patrick Gordon (1644-1736) immediately dispatched several fur traders, including James Le Tort, to gather information about the circulating rumors, offer condolences to the Delawares, and reprimand the Shawnees. The go-betweens were also instructed to remind as many Indians as possible of William Penn’s friendship. To renew that friendship, intermediaries brought the parties together at a series of treaty councils in 1728, in May at Conestoga, in June at the Quaker Meeting House in Philadelphia, and in October at the Philadelphia Courthouse. As a result, a frontier war was averted.

A New Generation of Go-Betweens

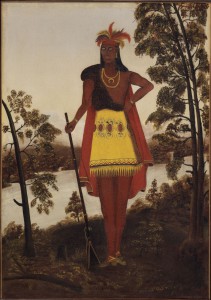

Following the councils of 1728, a new group of intermediaries emerged. The most prominent of these men were Shickellamy (d. 1748), an Onyota’a:ka leader living in the multi-ethnic town of Shamokin (present-day Sunbury and Shamokin Dam), and the German farmer Conrad Weiser (1696-1760) of Tulpehocken. They helped orchestrate a series of major treaties between the leaders of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Province of Pennsylvania in 1732, 1736, and 1742, which promoted trade and asserted control over the peoples living between Onondaga and Philadelphia. The population increased steadily between the two capitals, however, leading to more frequent disputes between Native Americans and their colonial neighbors.

Competing claims to the lands of the Ohio Country led to the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) between the English and French and their various Native American allies. After the French defeated a British expedition sent to capture Fort Duquesne on July 9, 1755, a group of Delawares began raiding provincial settlements from the Juniata River to Shamokin. Following the raid on the settlement at Penn’s Creek (October 16, 1755), the intermediaries hit the road once again. Scarouyady (d. 1758), an Onyota’a:ka leader, and Andrew Montour (c. 1720-72), a French-Onyota’a:ka-Algonkin guide, headed for Onondaga. In 1756 Kos Showweyha (d. 1756), an Onöndowa’ga (Seneca); Sata Karoyis, a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk);and William Lacquis, a Jersey Delaware, trod the paths multiple times between Philadelphia and the Delaware villages on the North Branch of the Susquehanna. Then, in 1758, the English-speaking Delaware Pisquetomen (fl. 1731-62) and the Moravian missionary Christian Frederick Post (1710-85) set out for the Allegheny Valley with the offer of Governor William Denny (1709-65) to renew the peace with the Ohio Indians provided they remained neutral. Remarkably, in the midst of the Seven Years’ War, this new group of intermediaries was able to ensure the loyalty of the Iroquois, appease the Haudenosaunee, and neutralize the Ohio Indians.

Decline of the Intermediaries

Hearts, however, were hardening. Many Native Americans had become disillusioned with the colonists’ apparent intent on achieving their end of acquiring land at any cost, which included the use by colonial intermediaries of presents, bribes, liquor, fake maps, and vague treaty statements. On the other hand, the majority of colonists, incensed by Indian attacks, believed the time for Indian councils had passed. Although intermediaries such as the Irish fur trader turned deputy Indian agent, George Croghan (1718-82), continued to negotiate treaties, the government of Pennsylvania called upon them less and less frequently.

Over the course of the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century, Indigenous and European go-betweens had often interpreted the kaleidoscope of cultures that existed in the region that became southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and northern Delaware. For many years they helped maintain a tenuous peace, but, with questionable methods such as fake maps and vague treaty statements, some intermediaries collaborated with the government of Pennsylvania and land speculators. This triggered resentment among many Native Americans, which played a role in the outbreak of violence and the Seven Years’ War.

Stephen T. Staggs is an Adjunct Professor of History at Calvin College and author of “The View from the Dutch Republic: Protestant Conceptualizations of Indians,” which appeared in De Halve Maen (Spring 2013). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- European Americans and Native Americans View Each Other, 1700-1775 (pdf, NationalHumanitiesCenter.org)

- The Indians of Pennsylvania (ExplorePaHistory.org)

- Shikellamy Historical Marker (ExplorePaHistory.org)

- Conrad Weiser's Diplomacy with the Ohio Indians (ExplorePaHistory.org)

- James Logan letter from Shikellamy and Allummapes (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)