Candy and Candymakers

Essay

Philadelphia was home to many of the nation’s leading candy makers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and played a key role in the development of the American candy industry. Large-scale candy production began in the city in the mid-nineteenth century, and by the turn of the twentieth century a number of major candy manufacturers were based in and around Philadelphia. The region remained an important candy-making center into the early twenty-first century, supporting both large manufacturers and small shops, including a shop in Old City that claimed to be the oldest continuously operating confectionery shop in the nation.

The modern concept of candy—sweet treats mass-produced as small pieces or bars—was unknown in early America. Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, small sweet treats generally consisted of fruits or nuts flavored with spices or sweeteners. These were sold by local food purveyors, or in some cases by “confectioners,” as those who specialized in sweet treats were known. Philadelphia grocer James Marsh advertised a variety of sweet products in 1763, as did confectioner Patrick Wright in 1775. Philadelphia was America’s preeminent international trading center in this period, with a substantial sugar trade with the Caribbean, giving the city’s food sellers access to a wide range of imported fruits and nuts as well as sugar and spices with which to flavor them. Although some confections were made locally, most were imported. Either way, sweet treats were an expensive delicacy in the eighteenth century, delights that only the wealthy could afford.

Beginning in the 1790s, thousands of French-speaking immigrants escaping revolutions in France and Haiti settled in Philadelphia, a number of whom established confectionery businesses. City newspapers included advertisements for many of these confectioners in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, a period in which Philadelphia was known for its confections. Writer Washington Irving (1783-1859), in his Stranger in Pennsylvania travelogue published in 1807, noted that Philadelphia was “famous for an excellent kind of confectionery, made from the drainings of sugar.” The Philadelphia Directory for 1816 listed over twenty confectioners operating in the city. Among those who rose to prominence in the first half of the nineteenth century were Sebastian Henrion and Sebastian Cheuveau, whose firms later merged, as well as Paul Lajus, Jeffrey Chew, George Miller, and Laurent & Maron.

Several Black confectioners were active in Philadelphia in this period. The 1838 Register of Trades of the Colored People of the City of Philadelphia and Districts listed names and addresses of five confectioners, and the 1856 Statistics of the Colored People of Philadelphia noted that seven “Confectioners and Pastry Cooks” were working in the city.

By 1857 some two hundred confectioners had businesses in Philadelphia, about half of whom made what would be considered “candy”; the other half specialized in other types of sweet treats, such as ice cream, jellies, and pastries. James Wood Parkinson (1818-1895), one of the most influential cooks in nineteenth-century America, did both. Parkinson operated fashionable restaurants and confectionery salons on Chestnut Street in the 1840s and 1850s. While renowned for his ice cream, an 1840 business directory noted that Parkinson’s salon also offered “a great variety of Bonbons … and Fancy Confectionary” and took orders “from any part of the United States for preserved fruits in sugar or brandy, sugar almonds, … [and] candy and confectionary in general.” Parker edited the Confectioners’ Journal from 1874 until 1895.

Machine-Based Production and the Rise of Chocolate

As in many industries, the Industrial Revolution brought machine-based bulk-production processes to candy making in the mid-nineteenth century. While traditional confectioners continued to fashion sweet treats by hand, others began producing them in large quantities in steam-powered factories. Advances in sugar refining—Philadelphia was one of the nation’s preeminent sugar refining centers—made large-scale production of sugar-based products profitable for many candy makers. Sweet treats, previously the province of the rich, became affordable to the masses. By the 1860s, Philadelphians could purchase a wide range of sugary products, from cheap “penny candies” to fine confections.

Coincident with this development was the emergence of chocolate as a favored sweet treat. Chocolate had been available in America since colonial times, but it was mostly used as a beverage and generally consumed unsweetened. In the latter part of the nineteenth century confectioners developed methods of processing chocolate—including adding sugar, and later, milk—that improved its texture and sweetened its taste, making it appealing as a candy. Consumption of chocolate soared in the United States in the late nineteenth century, with Philadelphia one of the leading producers.

Stephen F. Whitman (1823-88) was the most successful Philadelphia chocolate maker. Whitman first appeared in an 1844 city directory as a “fruiterer” at Third and Market Streets and in December 1845 advertised that he had just opened a new fruit and confectionery store at Twelfth and Market Streets, a large building that would serve as headquarters for his growing retail and manufacturing business for some forty years. In addition to developing new production processes, Whitman instituted what were then innovative business practices, such as investing heavily in advertising and creating distinctive packaging for his products, including the novel approach of selling candies in attractive boxes. Whitman’s Choice Mixed Sugarplums, introduced in 1854, was the first packaged set of candies to be sold in a printed trademarked box. (“Sugarplum” was a type of sugar-coated candy, not a fruit product.)

Henry Oscar Wilbur (1834-1917) was Philadelphia’s other major nineteenth-century chocolate maker. From a local Quaker family like Whitman, Wilbur opened a confectionery business in partnership with Samuel Croft (1834-1925) on North Third Street in 1865. Croft, Wilbur, & Company prospered and moved to larger quarters on Market Street near Twelfth Street, a few doors from Whitman. In 1884 the company separated into two businesses: H.O. Wilbur & Sons and Croft & Allen. Both operated large factories—Croft & Allen at Thirty-Third and Market Streets in West Philadelphia, Wilbur at Third and New Streets in the neighborhood later called Old City.

Famed chocolatier Milton Hershey (1857-1945) began his candy-making career in Philadelphia in this period, but was unsuccessful. A native of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Hershey opened a confectionery shop at 935 Spring Garden Street in Philadelphia in June 1876, hoping to capitalize on the expected crowds at the U.S. Centennial celebration that summer. The business failed, however, and Hershey left to pursue opportunities elsewhere before eventually settling back in Dauphin County and in 1894 founding what became the enormously successful Hershey Chocolate Company, in the town later renamed for him.

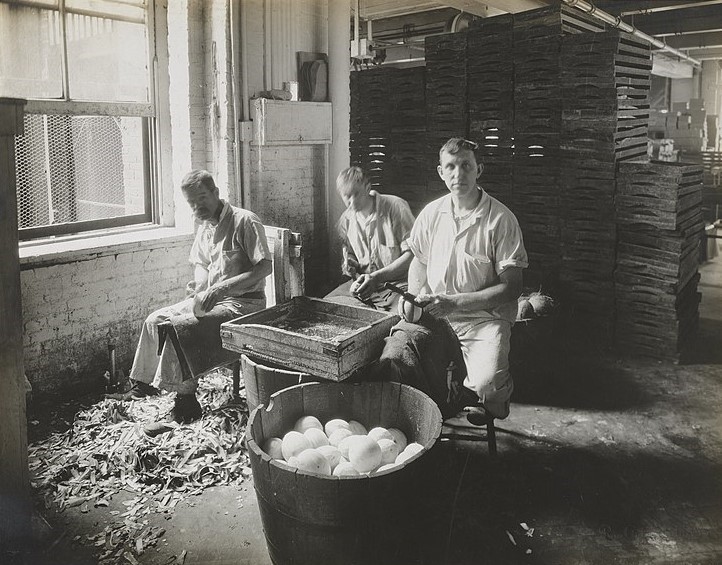

In 1882 there were 204 confectioners operating in Philadelphia, employing a total of 1,952 workers: 823 men, 738 women, and 391 children. (Women were an important part of the city’s candy manufacturing workforce from the industrial era through the early twenty-first century, often sorting candies on assembly lines or adding decorative finishes in the candy making process.) The two largest Philadelphia candy makers, Whitman and Wilbur, expanded significantly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Whitman moved to Sixth and Cherry Streets in 1886 after its building at Twelfth and Market Street was destroyed by fire, and then in 1906 to a very large factory at Fourth and Race Streets, just two blocks from Wilbur. Wilbur opened an additional plant in Lititz, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in 1913, while maintaining operations at its Old City location.

New Companies and Products

This period also saw the establishment of several new longtime candy companies as well as the introduction of many signature products. According to its company history, Richardson Mints began in 1883 with Thomas D. Richardson (1849-1935) selling his homemade mints at a Philadelphia department store counter. He later incorporated the company with his two sons in 1890. Goldenberg Candy Company, founded by Romanian Jewish immigrant David Goldenberg (1869-1935) and his family in 1890, created the Peanut Chew in 1917 as a military ration for World War I soldiers. Introduced to the general public after the war and manufactured at Goldenberg’s large plant at I and Ontario Streets in Kensington, the Peanut Chew enjoyed longtime popularity. In 1949 the company moved to a factory on West Wyoming Street in Feltonville. Asher’s Chocolates began when Canadian immigrant Chester A. Asher (1868-1944) opened a small candy store near Independence Hall in 1892. In 1896 he moved the business to Germantown, where it remained for a century. Tradition has it that George Renninger (1856-1944), a longtime employee of the Wunderle Candy Company in Northern Liberties, invented candy corn with company founder, German immigrant Philip Wunderle (1845-1929), in 1888.

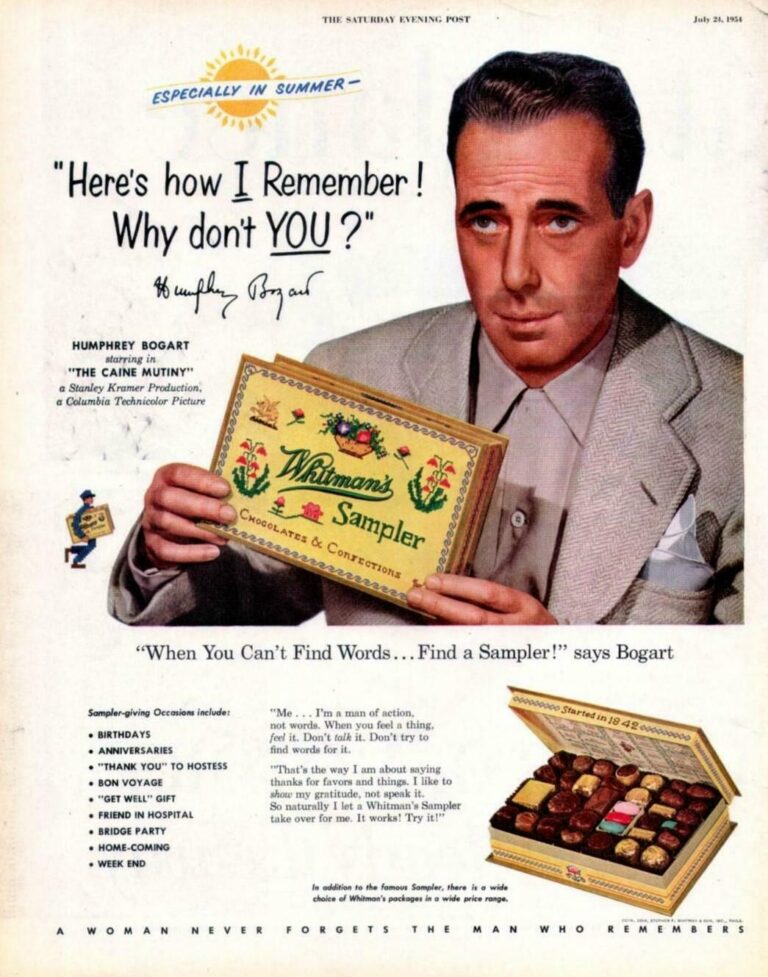

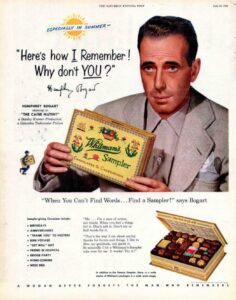

Isaac Rosskam (1839-1904) founded Quaker City & Confectionery Company at Germantown and Susquehanna Avenues in North Philadelphia in 1893 and that same year introduced Good & Plenty, a licorice candy in small hard-shell pieces that is considered the oldest branded candy in the United States. In 1894 H. O. Wilbur created the Wilbur Bud, a small conical shaped chocolate candy wrapped in foil. In 1907, Hershey introduced the very similar Hershey’s Kiss, prompting Wilbur to sue in 1909. The suit was unsuccessful, and while the Wilbur Bud remained a longtime popular candy, the Hershey Kiss ultimately became more successful. In 1912, Whitman introduced the Whitman’s Sampler, a selection of assorted chocolates in a signature yellow box, which included an accompanying diagram of the contents. (The name was a play on words: the box contained a sampling of various chocolates while designed to look like a stitched embroidered sampler.) Perennially popular, the Whitman’s Sampler became an iconic American product.

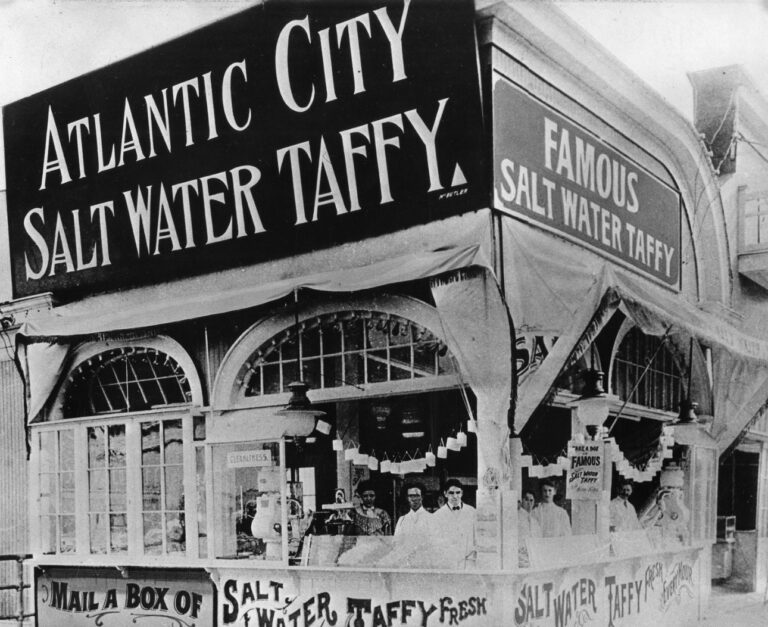

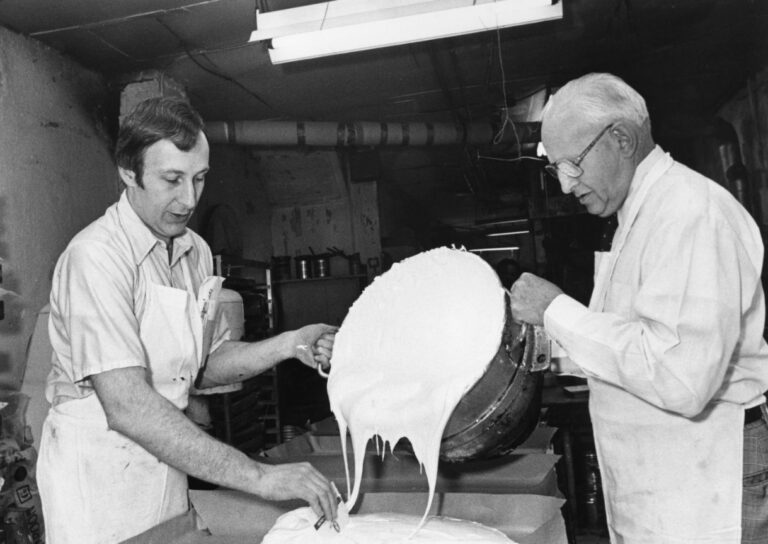

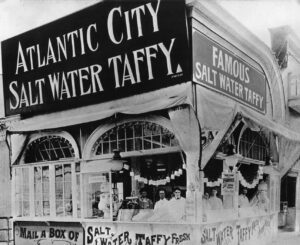

In 1905, five Blumenthal brothers, sons of German immigrants, founded Blumenthal Brothers Chocolate Company. Blumenthal produced popular candies Goobers, Sno Caps, and Raisinets at its factory at Margaret and James Streets in the Frankford neighborhood beginning in the 1910s. Other successful candies invented in the greater Philadelphia area at the turn of the twentieth century included salt water taffy, bubble gum, and Chiclets. Salt water taffy was invented in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in the 1880s and became a longtime favorite at New Jersey beach towns. Frank H. Fleer (1857-1921) established a chewing gum company in 1885 that introduced the candy-coated gum Chiclets in 1895, followed in 1928 by Dubble Bubble, the first successful bubble gum. In 1930, the company moved to a large building on North Tenth Street in Olney, where it operated for sixty-five years. Another local candy maker, Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation, founded in 1947, introduced Swell bubble gum, which it manufactured at its plant on Eagle Road in Havertown, Delaware County, Pennsylvania for fifty-five years. Both companies branched into making and selling trading cards with their bubble gum products.

In the early 1930s H.O. Wilbur phased out operations in Philadelphia and consolidated manufacturing at its Lititz location. About the same time, Wilbur acquired its former partner Croft & Allen, which had failed in the Great Depression. Even as these large candy makers closed or moved out of the city, new ones formed to take their place. Founded by immigrants in many cases, they often started in a family kitchen or as small storefront operations that grew over time into large or midsize producers. In 1922 Polish Jewish immigrants Samuel (1889-1972) and Anna (1891-1975) Zitner established Zitner Candy Corporation on North American Street in Kensington, and in 1947 Russian Jewish immigrant Sam Himmelstein (1906-93) founded Frankford Candy on East Venango Street in Harrowgate. Blasius Chocolates commenced operations in 1926 in Frankford and in 1996 took over Carl Miller’s Chocolate Factory, which was founded in the 1940s and later occupied the original Frankford Candy facility in Harrowgate. Frankford Candy had moved in 1955 to a large factory at Twenty-First Street and Washington Avenue in South Philadelphia, just a few blocks from Falcon Candy, which was founded in the 1940s and had a plant at Twenty-Third and Carpenter Streets. Plantation Chocolate Company, established in the 1930s, operated out of a large factory at Allegheny Avenue and Janney Streets in Port Richmond.

Ira (1898-1994) and Clayton (1889-1966) Minter established Minter Brothers Candies in 1920. Located on Lancaster Avenue in the Parkside neighborhood of West Philadelphia, the company grew to be quite large. Robert Minter (1930-2010), son of Ira, became president in the 1950s and moved the company to Bridgeport, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. He later sold Minter Brothers to a New York firm but remained in the business, acquiring several other Philadelphia candy companies, including Falcon, Plantation, Schellenberg, and Penn Candy. All but Plantation eventually closed.

Acquisitions, Relocations, Closures

The late twentieth and early twenty-first century brought a complex series of company acquisitions, relocations, and closures to the Philadelphia candy industry. Four firms moved to new facilities in Northeast Philadelphia: Whitman to Roosevelt Boulevard in the Far Northeast in 1961; Quaker City Candy & Confectionery to Grant Avenue, also in the Far Northeast, in the late 1960s/early 1970s; Goldenberg to State Road in Holmesburg in 1997; and Frankford Candy to Ashton Road near Northeast Philadelphia Airport in 2006. Whitman was acquired by a series of different companies beginning in the early 1960s, eventually becoming a division of Russell Stover Candies, which continued to manufacture Whitman products, including the iconic Whitman Sampler. The company closed the Northeast Philadelphia plant and ceased operations in the city in the early 1990s. Quaker City was sold several times beginning in 1973 and also moved out of Philadelphia. Hershey acquired Quaker City in 1996 and continued to make Good & Plenty.

Blumenthal remained under family management until 1969, when it was acquired by another company, which closed the plant in Frankford in 1984 and sold its popular brands to Nestle. Plantation Chocolate Company failed in the early 1970s and was acquired by Minter, who sold the business to John and Charles Crawford. In 1978 the Crawfords moved the company, renamed Plantation Candies, to Telford, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where it was still in operation in the early 2020s. Zitner remained under family management until 1990, after which it changed hands several times. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2018 but remained in business in the early 2020s, located on North Seventeenth Street in North Philadelphia. Goldenberg was acquired by Just Born, a candy maker based in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in 2003, but continued to make Peanut Chews at its Holmesburg plant. Falcon Candy closed after being acquired by Necco Wafers in 1996 and Blasius Chocolates closed in 2016. The region’s two bubble gum factories were sold and closed at the turn of the twenty-first century: Fleer in 1996 and Swell in 2003.

Both Frankford Candy and Asher’s Chocolate were still owned and managed by their founding families in the early 2020s. Asher’s moved from its longtime Germantown location to Souderton, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania in 1996. Frankford Candy, which had grown considerably and had several facilities in the city, expanded its Northeast Philadelphia facility and consolidated operations there in 2006. Frankford Candy developed licensing agreements with entertainment and media companies to sell candy in the form of well-known cartoon characters and action figures.

Small Family Companies

Large and midsize manufacturers aside, the tradition of making and selling candy in small family-run shops continued into the early twenty-first century, both in the city and suburban towns. Among the multigenerational family-run candy makers still in business in the suburbs in the 2010s and early 2020s were Duffy’s Fine Chocolates, founded in 1922 in Gloucester City, New Jersey, with an additional shop in Haddonfield, New Jersey; and Stutz Candy Company, founded in 1938 and managed by the Stutz family until 1965, and thereafter by the Glaser family, themselves longtime candy makers, with locations in Hatboro, Montgomery County, and Warrington, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and Ship Bottom, New Jersey. Stutz remained one of several local candy makers that produced Irish Potatoes around St. Patrick’s Day every year. Neither Irish nor potato, the origin of this candy, which consists of coconut cream balls rolled in cinnamon, is unknown, but it remained a longtime Philadelphia-area favorite.

In Philadelphia, Lerro’s Candies continued to be managed by the Lerro family, doing business into the late 2010s in the original shop that Italian immigrant John (originally Giovanni, 1880-1954) Lerro and his wife Anna (1884-1960) opened in 1916 on South Broad Street. The company later closed the shop and consolidated operations in its production facility in Darby, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Lore’s Chocolates was founded by Stephen Lore (b. 1945) in 1967 on Seventh Street below Market Street in Old City and purchased in 1986 by the Walter family, which continued the business in the early 2020s. The Walters were longtime Philadelphia candy makers—Anthony John “Tony” Walter Sr. (b. 1940) had previously worked at Minters, Plantation, and Goldenberg’s, managing the Goldenberg’s plant. Walter and his son, Tony Jr. (b. 1962), continued to make candy at Lore’s Old City shop, but also had a production facility at the former Goldenberg’s factory in Feltonville.

While some longtime family candy makers continued, others closed. Russian Jewish immigrant Louis Ostroff (1898-1989) began making candy in his kitchen in his late teens, opened a store in South Philadelphia in 1924, and later moved to 1706 Point Breeze Avenue, where he operated a retail and wholesale candy business until retiring in the 1970s. His son Solomon Ostroff (1927-2000) started a separate candy-making business in Kensington in 1953, after purchasing the Kensington Avenue store of another longtime Jewish candy making family, the Levan’s. Solomon’s son eventually took over the company and opened an additional retail store on Welsh Road in Northeast Philadelphia. The family-run business closed in 2015. Warner’s Candies, established in 1955 on Bristol Pike in Bensalem, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, was managed by the Warner family and operated at its original location until it closed in 2019.

For over a century, three generations of the Young family ran Young’s Candies, a small candy store on Girard Avenue in the Brewerytown section of North Philadelphia. Founded in 1897 by German immigrant John Young (originally Johan Jung, 1862-1912) and subsequently managed by his son and grandson, Young’s made candy in the German tradition. Among the products Young’s was known for was its clear toy hard candies made with molds passed down in the family. The company went out of business when Harry Young (1928-2006), grandson of the founder, died, but its clear toy candy tradition lived on when the proprietors of Shane Confectionery acquired some 250 of Young’s candy molds in 2007.

Shane Confectionery

Located on Market Street just above Front Street in Old City, Shane Candies had been the site of candy making since 1863. The Shane family took over the business in 1910 and in 2010 sold it to brothers Ryan (b. 1976) and Eric (b. 1980) Berley, proprietors of the Franklin Fountain ice cream shop a few doors away. Changing the name from Shane Candies to Shane Confectionery, the Berleys took a historical approach to candy making, using traditional recipes and production techniques. In the early 2020s Shane claimed to be the oldest continuously operating confectionery shop in the United States.

Shane Confectionery was established in the Old City neighborhood, where many of Philadelphia’s earliest confectioners had done business, and just a few blocks from the massive former Whitman and Wilbur factories. While these two key Philadelphia candy makers were long gone, their names lived on: In the 1980s the Wilbur factory at Third and New Streets was converted into an apartment complex called the “Chocolate Works.” Although the nearby Whitman factory at Fourth and Race Streets was demolished in 2016, some ten years earlier the site of the company’s 1960s headquarters on Roosevelt Boulevard in Northeast Philadelphia was developed into a shopping center known as “Whitman Square.”

In the early twenty-first century, industry mergers and acquisitions had consolidated most large-scale American candy manufacturing in the hands of a few dozen national or multinational corporations whose headquarters and production facilities were elsewhere. The Philadelphia area remained an important candy-making center, however. Two local companies—Frankford Candy and Just Born (the latter based in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, but with a large plant in Philadelphia)—remained among the nation’s largest candy producers, while numerous small to midsize companies continued the region’s centuries old candy making tradition.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects, and has curated exhibits and consulted on documentaries on them. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016, and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Foundations of the Union League of Philadelphia. He has served as consulting archivist and historian for the Philadelphia Orchestra, Mann Music Center for the Performing Arts, and Philadelphia Jazz Legacy Project. (Information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Milton Snavely Hershey in Philadelphia, 1876-1882 (Hershey Community Archives)

- Blumenthal Brothers Chocolate Factory (National Park Service)

- A Peek Inside South Philly's Lerro Candy (Hidden City)

- The Candy Making Past (Smithsonian Institution)

- Who Invented Candy Corn (History.com)

- Whitman's Chocolate Timeline (Russell Stover)