Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania

Essay

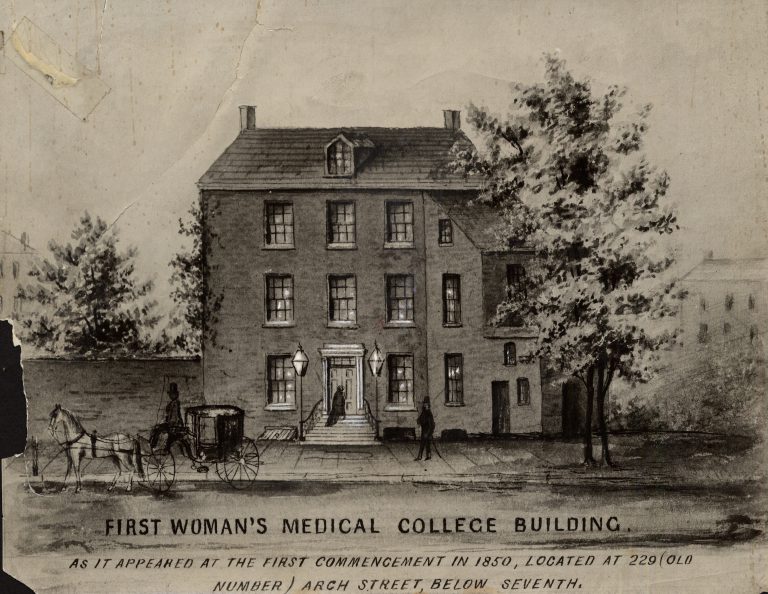

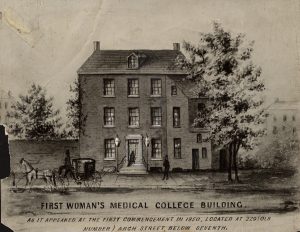

The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, founded in 1850 as the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, was the first medical school in the world for women authorized to award them the M.D. It was established in Philadelphia by a group of progressive Quakers and a businessman who believed that women had a right to education and would make excellent physicians. Renamed the Woman’s Medical College in 1867, the school trained thousands of women physicians from all over the world, many of whom went on to practice medicine internationally. The college provided rare opportunities for women to teach, perform research, manage a medical school, and, with the establishment of Woman’s Hospital in 1861, learn and practice in a hospital setting. It was the longest-lasting all-women medical school in the nation, until it became coeducational in 1970, admitting four men into what became the Medical College of Pennsylvania.

The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) was founded during an era of reform, just two years after the first woman’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York, asserted women’s rights to an education and a profession, among other rights. The college’s founders, early supporters, faculty, and earliest students reflected this reform mindset. The founders and early faculty included Quaker and non-Quaker activists for prison reform, abolition, and temperance. Founder William J. Mullen (1805–82) was a wealthy manufacturer turned philanthropist. A prominent advocate for prison reform, he worked as a prison agent at Moyamensing Prison and established the House of Industry in South Philadelphia, a neighborhood center that provided temporary shelter, job training, and English-language courses to immigrants and the homeless. Mullen served as the first president of the Board of Corporators of Woman’s Medical College. Others include Quaker activist-physicians Dr. Joseph S. Longshore (1809–79), longtime temperance and abolition advocate, and Dr. Bartholomew Fussell (1794–1871), a Chester County abolitionist, whose nephew, Dr. Edwin Fussell (1813–82), was one of the earliest faculty members. The inaugural class of 1852 included Chester County-bred Quakers Ann Preston (1813–72) and sisters-in-law Anna Longshore (1829–1912) and Hannah Myers Longshore (1819–1901), all of whom pursued rigorous education from childhood.

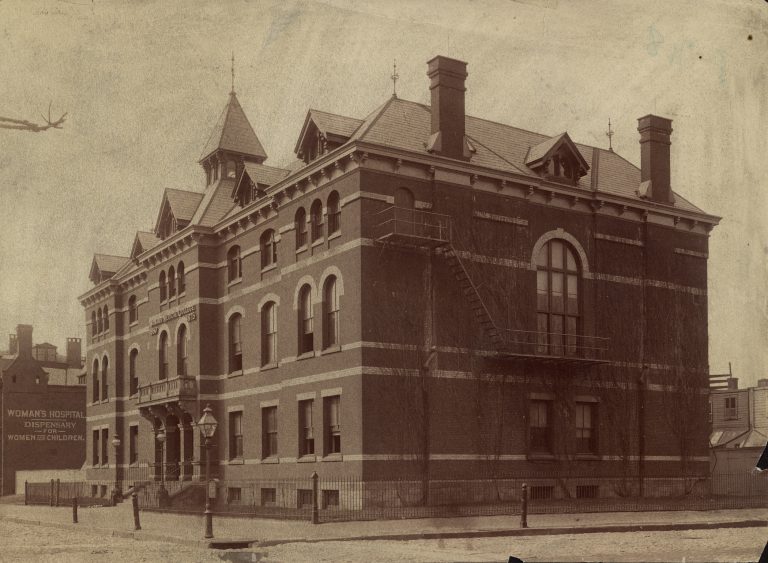

Ann Preston went on to become the first woman dean of WMCP—and of any medical school—in 1867, initiating a tradition of women deans at the college that continued unbroken for one hundred years. As dean, Preston determined to provide Woman’s Medical College students with the best clinical training available. Minimal even at traditional male medical schools, clinical training was even harder for female students to access. Preston arranged for her students to attend clinical demonstrations at the Blockley Almshouse (later known as Philadelphia General Hospital) in West Philadelphia and led the effort to establish the Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia on North College Avenue to provide care to women and children as well as clinical experience for the female faculty and students. The Woman’s Hospital became a flourishing independent institution known for its women surgeons, internships, and early nursing school.

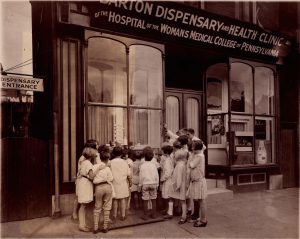

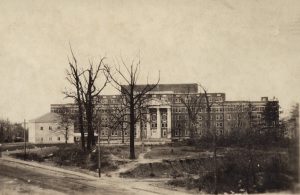

WMCP faculty and alumnae expanded students’ opportunities for academic and real-world medical experience in the late nineteenth century. In 1862, the college moved from its original location at 627 Arch Street into a well-equipped new building on North College Avenue next to the Woman’s Hospital, near Girard College and not far from another Quaker-supported initiative, Eastern State Penitentiary. In 1887, the college began an outpatient maternity service in South Philadelphia, and in 1895 established a nearby dispensary at 333-335 Washington Avenue. Students cared for women and children in homes throughout the neighborhood—dubbed the “South Pole” by the students for its geographical and social remoteness from their world on North College Avenue—gaining invaluable experience and providing healthcare to a marginalized community of immigrants and African Americans. In 1930, WMCP moved to the growing neighborhood of East Falls.

Women in medicine continued to struggle with acceptance in a man’s medical world, as demonstrated by what came to be known as the “Jeering Episode.” In 1869, after several rejected attempts, Ann Preston won the right to bring her students to Pennsylvania Hospital to take part in clinical instruction. When they arrived in the surgical amphitheater, male students catcalled, spat upon, and assaulted the women with spitballs and tobacco juice. Philadelphia newspapers picked up on the story and most sided with the women—not because they believed that women should be doctors, but primarily because the male students’ behavior was “un-gentlemanly.” The incident and ensuing publicity encapsulated the social debates about gender roles at the time, and the “Jeering Episode” became an essential element of the Woman’s Medical College’s identity for generations.

A number of important early women physicians graduated from WMCP: Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842–1906), the leading American woman medical scientist of the nineteenth century; Clara Swain (1834–1910), the first woman medical missionary, traveling to India in 1869; Anna Broomall (1847–1931), a master teacher of obstetrics who created an early program of prenatal visits; and Catherine Macfarlane (1877–1969), who conducted the first study in preventing pelvic cancers. WMCP always claimed a relatively diverse student body, inclusive regardless of race, ethnicity, or religion. It graduated some of the earliest African American women doctors, including Rebecca Cole (1846–1922), Eliza Grier (1864–1902), and Matilda Evans (1872–1935); the first Indian woman doctor, Anandibai Joshee (1865–87); the first Native American woman doctor, Susan LaFlesche Picotte (1865–1915); and other women M.D.s originally from China, Syria, and South America. The college also admitted Jewish students in the nineteenth century—earlier than many other medical schools—reflective of the growing Jewish immigrant community in South Philadelphia. In the mid-1940s the school accepted five Japanese-American students, at least three of whom had been imprisoned in internment camps. Many of these women went on to serve their respective communities.

One hundred and twenty years after its founding, in 1970, the Woman’s Medical College admitted men and changed its name to Medical College of Pennsylvania. In 1995, the Medical College of Pennsylvania merged with Hahnemann University’s medical school (founded in 1848), operating under several organizational structures until it was established as the Drexel University College of Medicine in 2002. The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania played a key role in establishing Philadelphia as a pioneering center for medicine and a leader in women’s higher education.

Melissa M. Mandell is a Philadelphian and public historian who has most recently worked on digital history projects for the Drexel University College of Medicine Legacy Center Archives & Special Collections, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Changing the Face of Medicine: Celebrating America's Women Physicians (National Library of Medicine)

- Doctor or Doctress: Explore American History through the Eyes of Women Physicians (Drexel University Legacy Center)

- AMWA’s History of Success (American Medical Women's Association)

- Woman's Medical College, Hospital and School (Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, Athenaeum of Philadelphia)

- Female Medical College (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Former First Medical College for Women Becomes Luxury Apartments (Curbed)