Eastern State Penitentiary

Essay

Eastern State Penitentiary, considered by many to be the world’s first full-scale penitentiary, opened in Philadelphia in 1829 and closed in 1971. Known for its system of total isolation of prisoners and remarkable architecture, Eastern State proved to be one of the most controversial institutions of the antebellum period. Abandoned as a prison in the 1970s, Eastern State became a popular museum of penal history and continued to serve as a stark reminder of the failure of isolation as a humane model of punishment.

Eastern State emerged from the concerns of prison reformers in Philadelphia in the late eighteenth century, when prisons held accused criminals only until their trials. If convicted, prisoners faced public and corporal punishment. Following the American Revolution, reformers including Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) argued for a more humane and systematic approach to treating criminality and began advocating for a system of incarceration as the primary form of punishment. Isolation, he argued, would provide the criminal with an appropriate environment to repent, reflect, and ultimately reform. In this spirit, in 1787 advocates for reforming Philadelphia’s prisons formed the Pennsylvania Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons under the direction of Bishop William White (1748-1836), though Rush provided the driving force. Many modern accounts attribute Eastern State’s early approach to Quaker inspiration, but considerable evidence suggests that the penitentiary’s strategies were grounded in Enlightenment thought in England that made its way across the Atlantic and took hold in the prison society.

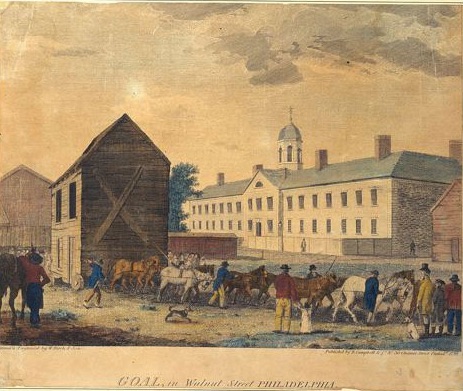

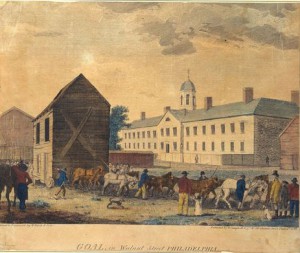

Experiments with prisoner isolation began in the 1790s at the Walnut Street Jail, located between Fifth and Sixth Streets behind the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall). Opened in 1775, the Walnut Street Jail housed accused men, women, and children together in common rooms until they went to trial. In the aftermath of the Revolution, critics of this “den of debauchery” and “school of crime” successfully petitioned the state to eliminate harsh public punishments such as whippings, brandings, and beatings in favor of a new experiment in isolation and labor. All prisoners were sentenced to labor within the walls of the prison, thereby moving punishment from the public to the private—an important shift in penological theory.

In 1789 and 1790 Pennsylvania passed legislation to convert a portion of the Walnut Street Jail into a penitentiary house, where more serious offenders would serve their sentences in complete isolation. Advocates of isolation, who argued for the humanity of silent reflection over the barbaric punishments of the past, initially viewed the experiment positively. However, by the late 1790s the system began to break down due to severe overcrowding and mismanagement.

Total Isolation on a Large Scale

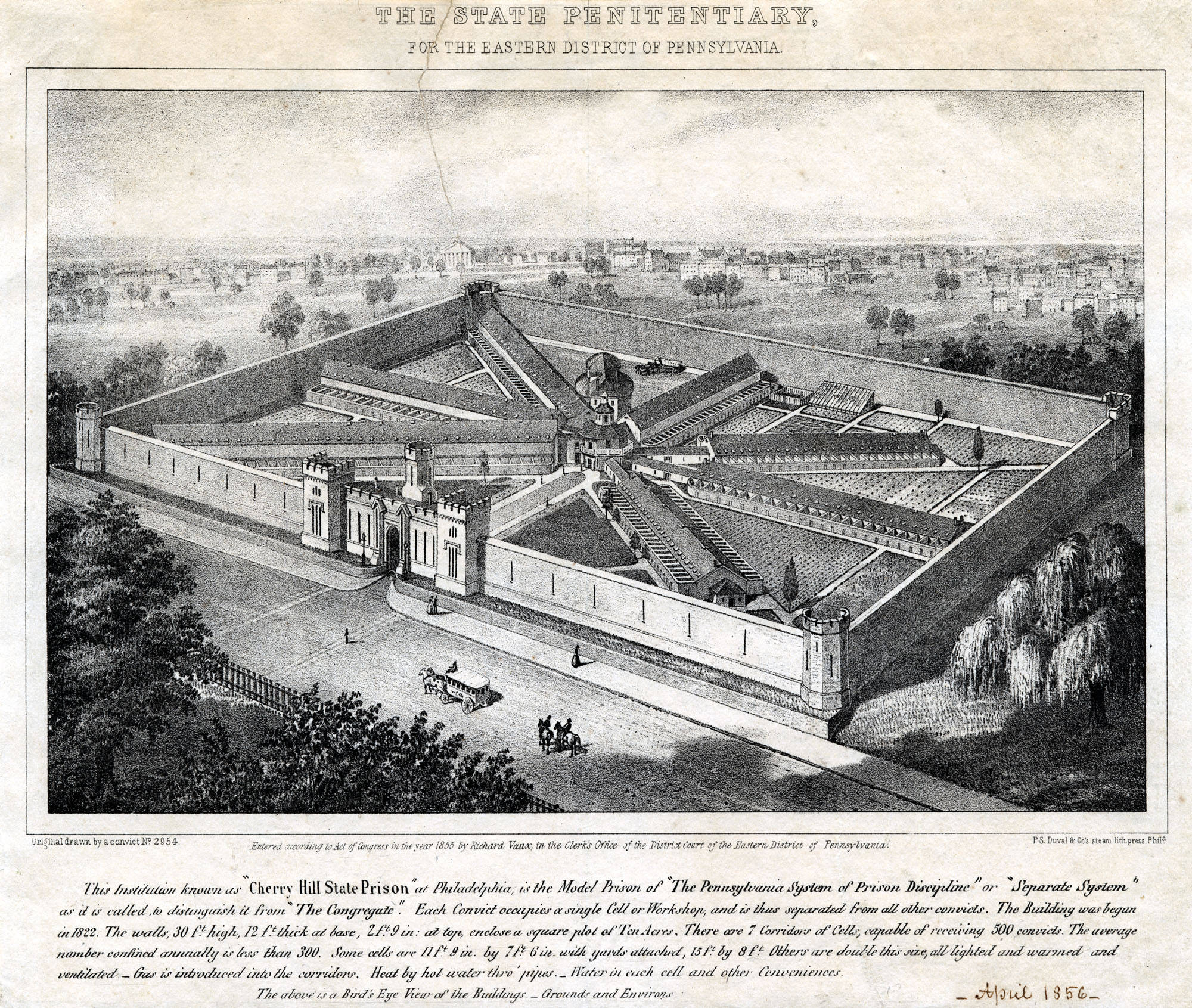

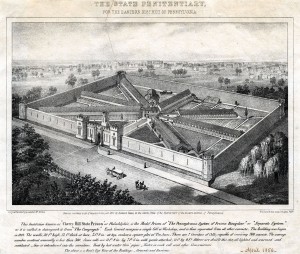

In response to prison society reformers’ agitation for a new penitentiary based on the concept of total isolation, in 1821 the Pennsylvania Legislature appropriated $250,000 for Eastern State. Reformers chose a site northwest of the city (later Philadelphia’s Fairmount neighborhood), where they believed the high elevation would promote good air flow and contribute to healthy prisoners. In the competition to determine who would design the new penitentiary, prominent Philadelphia architect William Strickland (1788-1854) and British-trained architect John Haviland (1792-1852) both submitted plans. The state awarded Haviland the project and a $100 prize.

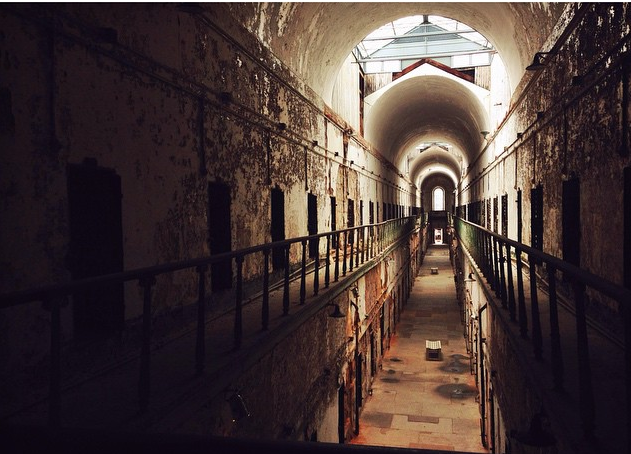

Haviland faced the formidable task of designing an institution based entirely on prisoner separation. To meet each prisoner’s needs in isolation, each cell needed to be equipped with a rudimentary toilet and central heat. Haviland chose a “hub and spoke” design or a radial plan, which would facilitate the observation of prisoners as well as properly ventilate the building. Prisoner health and the avoidance of miasmas (bad air) were among the concerns of reformers, who remembered all too well the deadly epidemics of the Walnut Street Jail. The penitentiary’s interior earned Haviland high praise, and Eastern’s imposing gothic facade made it one of the most recognizable buildings in nineteenth-century America.

Opened in 1829, Eastern State’s unique system of solitary confinement and labor became known as the “Pennsylvania System” or “separate system.” This new system effectively merged the best qualities of the Walnut Street Prison: solitary confinement and labor. To preserve isolation and anonymity at all times, prison policy required inmates to wear hoods whenever overseers moved them around the penitentiary. To help offset the cost of incarceration, the state required prisoners to do work in their cells, including shoemaking, weaving, and chair caning. They ate three meals a day in their cells and exercised one to two times daily in small exterior exercise yards. On Sundays local ministers offered sermons in the corridors. The only other visitors allowed were members of the prison society or a local minister employed by the penitentiary known as the “moral instructor.” The Philadelphia Bible Society provided prisoners with Bibles, and when the number of German prisoners began to rise in the 1840s, the German Society provided German Bibles. Reformers no doubt believed a Bible could be a source of consolation for lonely prisoners, but many prisoners struggled with illiteracy and the Bible remained inaccessible to them.

Population Reflected Immigration

Early intake records reveal a diverse prisoner population. African Americans were always disproportionately represented, and changing immigration patterns brought Irish and German inmates in the 1840s and 1850s and Italians and Eastern Europeans between the 1880s and 1920s. Until 1923, the prisoners included women. The number of women committed to Eastern State was always small compared to the number of men, but their presence prompted officials to hire a “matron” to oversee them. Women served similar sentences to men and committed the same crimes. In the nineteenth century, the vast majority of prisoners had committed property crimes including theft (predominantly horse theft), burglary, and robbery. Most served two-year sentences though many served longer terms for more serious offenses such as murder.

From the outset, prison administrators struggled to maintain control. Many prisoners refused to work, sabotaging their tools and equipment or using their tools to fashion knives to attack overseers. Prisoners (especially Irish Catholics) frequently refused visits from the Protestant moral instructor or pretended to accept religion to gain shorter sentences. Still others found ways to subvert the system of silence by sending notes through plumbing lines or tapping code on walls of adjoining cells.

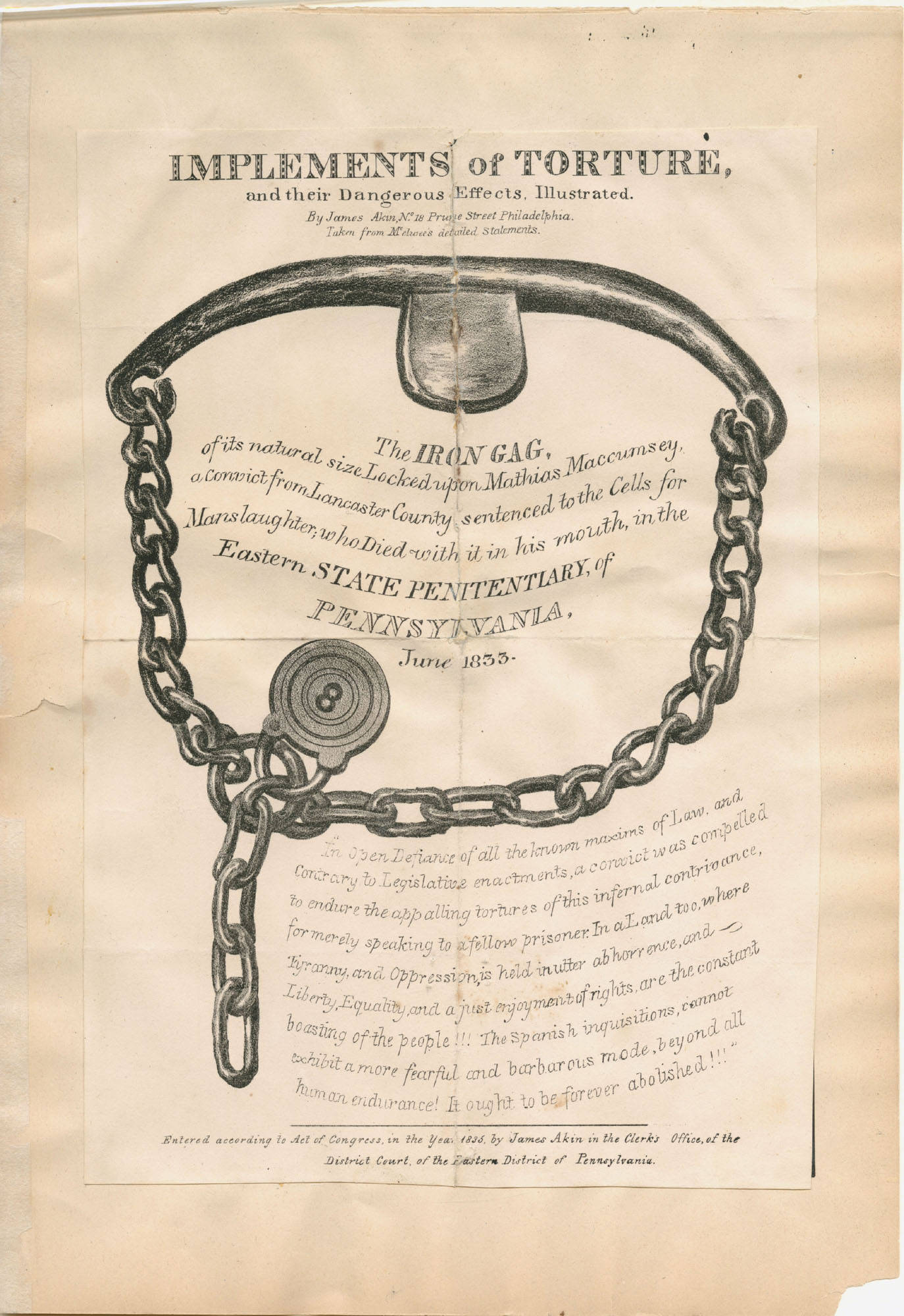

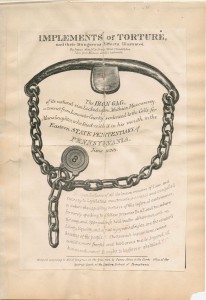

In 1833, just four years after Eastern State opened, a fiery public scandal erupted when prisoner Mathias Maccumsey died after prison officials subjected him to a torturous instrument known as the “iron gag” to prevent him from talking. The gag fit over the prisoner’s tongue (like the bit of a horse bridle) and attached to his arms pinned behind his back. The penitentiary physician declared the cause of death to be “apoplexy.” Although Eastern State’s administrators were exonerated in an exhaustive investigation, they tried to cover up the death and the institution’s reputation suffered a serious blow.

Despite problems with prisoner management, Eastern State’s supporters touted the Pennsylvania System as the solution to crime and punishment. Financially, however, Eastern State was less successful than the “Auburn Plan” for penitentiaries developed in New York. There, prisoners labored in large factory-like conditions by day and returned to isolation at night. The factory labor system made Auburn-style prisons largely self-sufficient. Eastern State, meanwhile, struggled with costs because the craft goods like shoes, chairs, and weaving produced by prisoners in isolation could not financially sustain the institution.

Charles Dickens Among Critics

Supporters of Eastern praised its humane approach to prisoner treatment while critics claimed that isolation led to insanity and even death. A heated pamphlet war broke out between supporters of the Pennsylvania and Auburn systems. Charles Dickens (1812-70), perhaps the Pennsylvania system’s most damning critic, visited in 1842 and in his American Notes argued that while reformer’s intentions remained humane, the system itself amounted to torture. Eastern’s physicians acknowledged instances of insanity but attributed them largely to African American prisoners, whom they viewed as predisposed to mental illness because of their “unique” nature. Officials also argued that overstimulation in the form of masturbation contributed to cases of insanity.

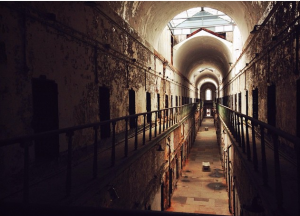

By the 1850s problems with prisoner management, overcrowding, and mental health led Eastern’s officials to slowly relax the rules of isolation. Overcrowding prompted construction of even more cells and, beginning in the 1860s, officials frequently housed more than one prisoner per cell. While the Auburn Plan had been adopted by many states, those who had adopted the Pennsylvania System quickly abandoned it because of problems with profitability and prisoners’ health. Nevertheless, many new penitentiaries adopted Haviland’s hub-and-spoke design as the best method for surveillance of prisoners. Examples of Haviland’s hub- and- spoke design can be found throughout the world including Japan, Russia, and Brazil.

In 1913, Eastern State officially declared the Pennsylvania System dead though it had not been closely followed for decades. In a struggle to catch up with congregate-style prisons of the day, Eastern converted many of the useless individual exercise yards into congregate workshops. Space between cellblocks became used for sports and recreation, including a baseball field and football field. Italian prisoners added bocce ball to the prison’s many activities.

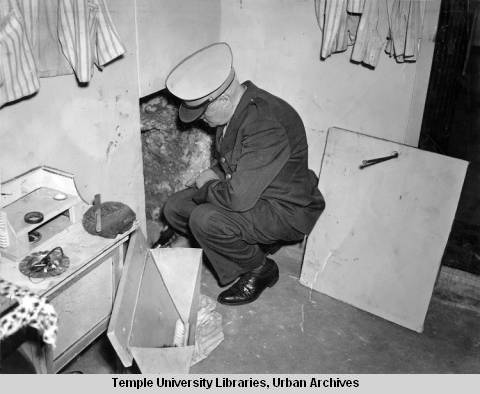

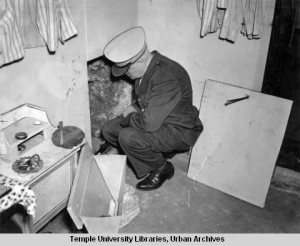

During the twentieth century Eastern continued to be rocked by scandals. In 1929, while serving an eight-month sentence, Al Capone (1899-1947) enjoyed luxuries denied to other prisoners such as an oriental rug and radio. In 1933, prisoners rioted and set fire to their cells to protest overcrowding and a lack of recreation facilities. In 1945, Eastern experienced perhaps the most sensational escape in its history when notorious bank robber “Slick Willie Sutton” (1901-80) escaped with eleven other men through a tunnel under the wall. In 1961, after the largest riot in the Eastern’s history, Pennsylvania began serious discussions about closing the penitentiary. While initially isolated from the city, the prison had become surrounded by the neighborhood of Fairmount, which grew quickly from the late nineteenth century into the twentieth. Baldwin Locomotive (at Broad and Spring Garden) and many local breweries spurred the development of housing, and by the 1960s Fairmount had become a diverse working class and middle class neighborhood. Neighbors as well as state officials were increasingly nervous about public safety and the ability of the aging institution to properly manage the prison population.

Eastern State as Tourist Attraction

Eastern State finally closed its doors in 1971, and the remaining prisoners transferred to Graterford State Prison. The Philadelphia Streets Department briefly used the site for storage but performed no maintenance on the building, which quickly decayed and became the target of vandals. In 1984 the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority considered proposals to convert the site into commercial uses, including plans for a shopping center and condominiums. Concerned that a significant piece of Philadelphia’s history would be lost if development proceeded, a group of preservationists, neighbors, historians, and architects created the Eastern State Penitentiary Task Force with the goal of saving Eastern State as a historic site. Limited hard-hat tours began in the late 1980s, and in 1991 the site received its first funding from the Pew Charitable Trusts to perform necessary stabilization and preservation. Continuing as an independent nonprofit organization, Eastern State Penitentiary became committed to interpreting the institution’s complex past while raising important questions about the contemporary justice system.

By the first decades of the twenty-first century, Eastern State Penitentiary had become one of Philadelphia’s most popular tourist destinations. Audio and guided tours and other interpretative programs highlighted the significant role Eastern State played in penitentiary reform while art installations and public programs addressed contemporary issues in incarceration. While remaining the site of several very popular annual events including a Bastille Day celebration and Terror Behind the Walls, a haunted house fund-raiser, Eastern State also became actively involved with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. Striving to make connections between the past and the present in order to effect social change, Eastern State added programs and exhibits such as “The Big Graph,”: a 16-foot-tall, 3,500-pound plate steel sculpture depicting current rates of incarceration around the world.

Once among the most recognized buildings in the United States, Eastern State Penitentiary encapsulated the hopes and anxieties of a generation of reformers. Its formula of isolation and labor seemed to provide the logical solution to crime and punishment, yet the crumbling cells and cavernous cellblocks became vivid reminders of failure. As a historic site, Eastern State became a site for exploring this complex history while inviting the public to engage in discussion of the future of incarceration.

Jennifer Lawrence Janofsky, Ph.D., is the Giordano Fellow in Public History at Rowan University and curator of the Whitall House at Red Bank Battlefield. She has served as a historical consultant for Eastern State Penitentiary, which was the subject of her doctoral dissertation at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Questions of ethics haunt Eastern State Penitentiary (WHYY, July 26, 2011)

- This year's terror at Eastern State Penitentiary will grab visitors (WHYY, September 18, 2014)

- Eastern State Penitentiary focus shifts from Al Capone to prison policy (WHYY, May 6, 2016)

- For the first time, historic prison offers tours of the hospital (WHYY, May 1, 2017)

- Philly's Bastille tradition goes out with a bang (WHYY, July 16, 2018)