Girard College

By David A. Canton | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The history of Girard College, a boarding school for children from poor families headed by single parents or guardians, reflects the history of Philadelphia and the nation. Opened in 1848, Girard College was established under a bequest from wealthy philanthropist Stephen Girard (1750-1831), whose will specified a school for “poor white male orphans.” Girard College offered educations that otherwise would have been unattainable, but only for white boys. By the mid-twentieth century the expansion of Philadelphia’s Black population and the quest for civil rights led to campaigns to desegregate the school. In 1968, mass protests and litigation succeeded in opening the doors to African American children, and by the twenty-first century Girard College enrolled students of diverse races, cultures, and ethnicities.

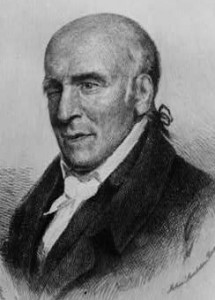

The bequest for Girard College was made possible by the success of Stephen Girard, who at the time of his death in 1831 was one of the wealthiest men in the United States. Born in France and later naturalized as an American citizen, Girard was sightless in his right eye, but his disability did not prevent him from accomplishing tremendous tasks. Like his father, he became a seaman and by age twenty-three was captain of his own ship. While conducting trade in American and Caribbean ports, in 1776 Girard was forced to dock in Philadelphia by a British blockade of New York. He sold his ship and opened a store on Water Street, and remained a trader and investor in Philadelphia for the rest of his life. For a brief time, beginning in 1777, he lived with his wife, Mary Lum, in Mount Holly, New Jersey.

As he became legendary for his business acumen in trade and finance, Girard also expanded his activities to public service and philanthropy. When a yellow fever epidemic hit the city in 1793, Girard volunteered for what many thought was the worst job in the city, to run Bush Hill Hospital. In 1802, he served on the Councils of the City of Philadelphia, and he donated money for city works projects. In 1829, Girard lent the state of Pennsylvania $100,000 to create a canal-railroad link between the Schuylkill and Susquehanna rivers. Girard’s ability to blend his pursuit of wealth with public benefits—a practice historian Sam Bass Warner later labeled privatism—worked to the city’s advantage, at least in its early years.

Girard’s Bequest

At the time of his death, Girard’s estate was valued at $7.5 million. His 39-page will designated funds for many purposes, including the creation of Delaware Avenue on the waterfront; lifetime pensions for his former slave, Hannah, and other women of his household; and $2 million to construct a school for “poor white male orphans” and operate it in perpetuity.

In detailed instructions for Girard College, the benefactor directed that preference be given to applicants from Philadelphia, New York City, and New Orleans, three cities where he conducted business. Girard, not formally educated himself, wanted the students to receive a useful education in basic subjects, foreign languages, science, and the “purest principles of morality.” He prohibited ordained clergy from working at the school or even entering the campus, a reflection of his view that secular values created prosperity for individuals, Philadelphia, and the nation.

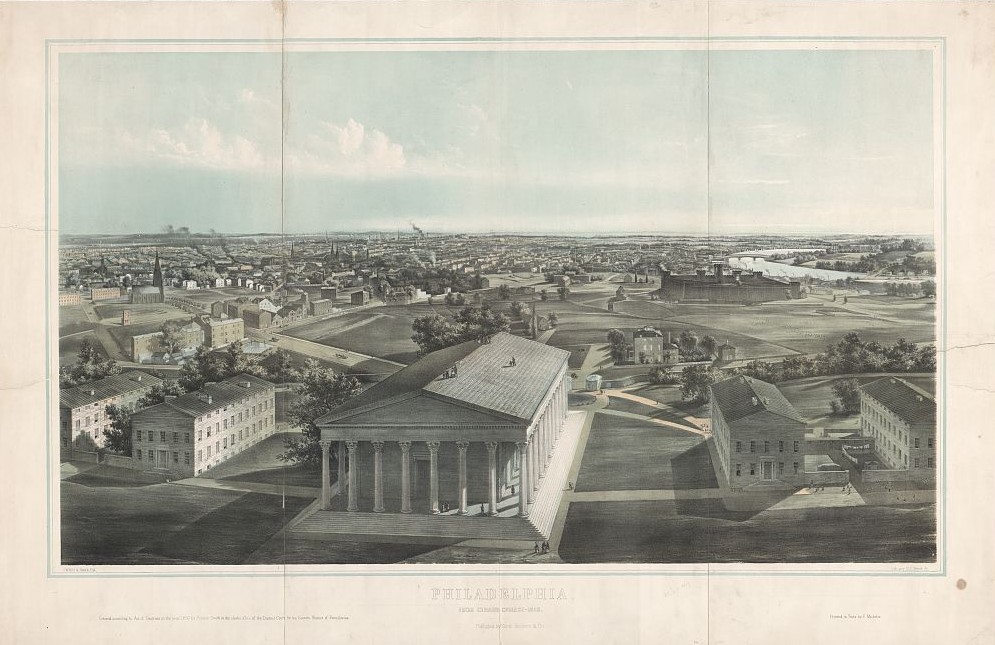

Girard also specified the architectural style of the school and the site, originally Market Street between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets but changed by Girard before his death to the less-developed area north of Poplar Street near Ridge Avenue. He insisted that a ten-foot high, fourteen inch thick wall surround the 43-acre campus, both to keep students from leaving and to protect them from the excitements of city life, such as crime, vice, and alcohol. In keeping with the culture of the Jacksonian era, Girard insisted that the architecture should be simple and functional, so that it would communicate a democratic and populist appeal. The resulting structure – designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, the Philadelphia-born architect of the U.S. Capitol dome and a founder of the American Institute of Architects – reflected the Greek revival movement in nineteenth-century American architecture. Begun in 1833 and completed in 1847, Girard College symbolized civic virtue and nationalism.

Girard College provided opportunity for young white males to become educated and escape poverty. During the nineteenth century, boys whose fathers had died usually had to leave school to earn a living. Without education, they were relegated to low-paying, menial jobs. The achievement of Girard College was in allowing poor, young white males to have an educational experience similar to middle and upper class males by allowing them to live on campus and invest time in their education.

Will Challenged

Many of Girard’s relatives were surprised and upset that he left the bulk of his estate to build a school. From 1833 to 1982, a number of individuals challenged the legality of Girard’s will. In 1836, Girard’s siblings, nieces, and nephews (he had no children) sought to break the will so they could inherit the fortune. They claimed that the City of Philadelphia could not be an executor of the will and hired Daniel Webster, who argued that banning clergy from the college was immoral. In 1844, the United States Supreme Court upheld the will as a binding legal document.

While an extraordinary act of philanthropy, the creation of Girard College also reflected views of race and gender held by Girard and most whites of his time. A school for “poor white male orphans” excluded female and non-white children who needed an education. In 1891, Nathan Mossell, one of the first Black physicians in Philadelphia, tried to desegregate Girard College by assisting Frank Wilson, a poor Black male orphan, with his application to Girard. Mossell’s effort failed. The courts did not get involved. The school simply said no, and that was the end of it.

New efforts to desegregate Girard College began after World War II as the civil rights movement gained momentum in the South and across the nation. Girard College, by this time surrounded by a predominantly Black neighborhood and experiencing declining enrollment, stood as an especially striking example of segregation and exclusion.

In 1953, E. Washington Rhodes, a Back attorney and editor of The Philadelphia Tribune, an African American newspaper, offered free legal aid to any Black parents who tried to enroll their children in Girard College. No one took the offer, but on July 23, 1953, Raymond Pace Alexander, a Black attorney and city councilman, introduced Resolution 433 declaring that because Girard College was governed by elected officials and received tax exempt status, it must admit Black male orphans. Although the resolution passed, Girard refused to desegregate. Many citizens and alumni supported Alexander, who argued that it was wrong for them to be paying taxes to a city whose Board of Directors of City Trusts prohibited African Americans from attending Girard College. In the wake of Brown vs. Board of Education (1954), the U.S. Supreme Court decision ordering desegregation of public schools, Alexander and others led the fight to desegregate Girard College. In April 1957, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that Girard College had violated the Fourteenth Amendment but did not order that boys of color must be admitted. In order to avoid admitting Black boys, the Board of Directors of City Trusts, until this time a Philadelphia public agency, converted itself into a private board of governors.

Integration Battle

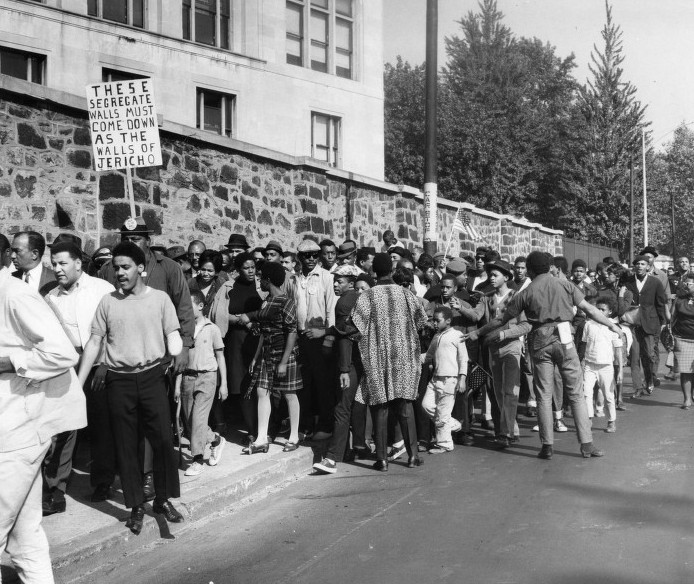

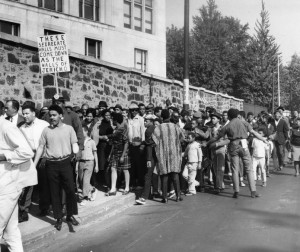

A decade later, civil rights leaders in Philadelphia again sought to open the doors of Girard College to African Americans. Cecil B. Moore, a Black attorney and president of the Philadelphia Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), filed suit against the city to desegregate the school. Protestors gathered outside of the Girard College with picket signs, attracted media attention, and pressured local officials to desegregate.

On March 6, 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Girard College had practiced discrimination and had violated the Fourteenth Amendment. On September 11, 1968, Girard College admitted four African American boys and two Asian American boys, but it remained all-male until September 3, 1982, when girls were admitted for the first time. In the 1980s, administrators also allowed clergy to enter the campus, although they were prohibited from discussing religious issues with students. Girard College’s admission policy also expanded the definition of “orphan.” In order to qualify for admission, students must come from a single, non-married parent, male or female, household.

In its history, Girard College has graduated more than 20,000 orphans and children from financially needy families. By 2011, the school offered a college-preparatory curriculum, and eighty-five percent of its 475 students in grades one through twelve were African American. Beginning in 2009, Autumn Atkins Graves became the first African American and female president of the school. The presence of students of color and female students reflects the civil rights struggle and the ways that Philadelphia, and the nation, have changed over time. A museum and archive in the school’s Founder’s Hall remains a testament to the lasting, and changing, legacy of Stephen Girard.

David Canton is Associate Professor of History at Connecticut College and author of Raymond Pace Alexander: A New Negro Lawyer Fights for Civil Rights in Philadelphia (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, University of Pennsylvania Press

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- The Will of Stephen Girard

- Girard College

- Education Resources on School Desegregation: Girard College (National Archives Mid-Atlantic Region)

- Civil Rights in a Northern City (Temple University Libraries)

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attends rally at Girard College (Temple University Libraries

- Founder's Hall (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Cecil's People (History Making Productions)