Almshouses (Poorhouses)

By Mara Kaktins

Essay

From the late seventeenth century to the early twentieth century, almshouses offered food, shelter, clothing, and medical care to the poorest and most vulnerable, often in exchange for hard labor and forfeiture of freedom. Those who entered the Philadelphia region’s almshouses, willingly or unwillingly, rarely accepted this exchange and often protested their treatment or blatantly defied authority.

Early in the colonial era, poor, infirm, and mentally ill Philadelphians were cared for privately by the community. Churches, trade and ethnic associations, and family members took care of their own. A prime example of this was the Friends Almshouse, built in 1713. Located on Walnut Street between Third and Fourth Streets, this poorhouse run for and by Quakers provided a sanctuary for poor, widowed, and aged Friends.

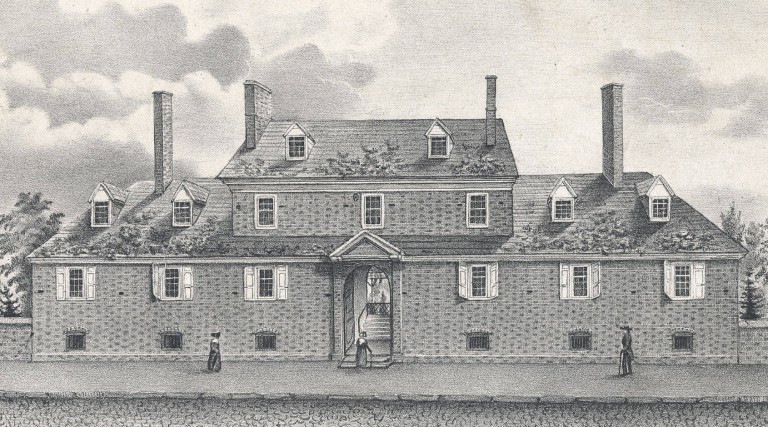

With an increase in population and a growing influx of immigrants, the Philadelphia public officials soon saw the need for city-run poor relief and established the Overseers of the Poor, an organization made up in large part of Quakers. The Overseers, later renamed the Guardians of the Poor, were to oversee all subsequent almshouses in Philadelphia. These included the Philadelphia City Almshouse, a complex completed in 1732 and encompassing the block between Third and Fourth and Spruce and Pine Streets, previously a rural green meadow. Built and organized like a large domestic house, this almshouse was never meant to accommodate more than forty or fifty people at a time. Only those in dire need such as orphans and the very sick and elderly were supposed to be admitted. For others in need, the city preferred “out-relief” in the form of small amounts of money, clothing, firewood and food.

The Philadelphia Almshouse and all subsequent almshouses in the city struggled with funding. Mismanagement, corruption, and an ever-growing indigent population created an almost constant need for more money, and poor taxes were never enough to cover expenses. To dispense with the poor while simultaneously raising money, almshouses across the colonies engaged in bonding out children. This involved indenturing children and even young adults to paying members of the community, who in return agreed to teach their charges useful skills and in some cases to educate them to some degree. This system had unlimited potential for abuse and sorrow. Children could easily be forcibly removed from their parents who would never see them again. In fact, almshouse authorities preferred to place children far from their homes to discourage runaways and to keep disgruntled parents from complaining about the condition in which their children were kept.

Reforming and Teaching Skills

As the eighteenth century progressed, attitudes began to change away from just feeding and clothing the poor, toward reforming and teaching them skills. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) expressed his opinion that poor relief itself (meaning handouts) caused indigence. Almshouses began to employ their tenants in attached workhouses, where they were made to weave cloth, manufacture and repair shoes or linens, make buttons, and other such activities. These tasks were meant to defray the costs of running the almshouse while teaching the inmates morality through labor. Generally, both goals failed. The products of task work proved unprofitable due to a combination of corruption and mismanagement, and inmates resented being made to work for no pay.

After the second quarter of the eighteenth century, admissions to the Philadelphia Almshouse increased steadily as the general population grew. By the 1760s, the almshouse was vastly overcrowded, with a population exceeding 200 persons, and the building proved too small to implement new philosophies regarding poor relief. As the city expanded, the almshouse property also became prime real estate in the neighborhood later known as Society Hill. In 1767, the institution moved to less-expensive land more distant from the city core: a plot bounded by Tenth and Eleventh Streets from Spruce to Pine. Officially known as the Philadelphia Almshouse and House of Employment, the new complex was most often called the Bettering House, with more than a little hint of irony.

The Bettering House was, at the time, the largest building in the American colonies and a source of great pride for Philadelphia. Surrounded by lavish pleasure gardens, the institution was an attraction visited by wealthy Philadelphians and travelers, who reported in their diaries about having dined or taken tea in the gardens. Some, however, were repulsed to be surrounded by such splendor while observing the poor as though they were animals in a zoo.

Unlike the first almshouse, the Bettering House rigorously controlled inmates’ lives. Authorities segregated the population by age, race, gender and even “good” versus “bad” poor, with a goal of reforming the “failed” indigents, who were increasingly seen as criminal. The poor were expected to accept their place in society and taught how to properly fulfill their role once released. Punishment, religious instruction, task work, and, at times, solitary reflection, were employed to this end. Those who were capable were to work six days a week, between eight and ten hours a day, not including a half-hour break for breakfast and an hour for dinner. The overseers complained in daily journals that the population swelled during the tough winter months, and inmates departed in droves once they were clothed, fed, the weather improved, or they were cured of their particular ailments, often to return again the following year. It was not uncommon for prospective inmates to complain of “sore legs” upon entry in order to gain shelter for a few cold months and avoid labor.

Rural Almshouses

While the greatest concentration of those in need tended to center in cities, almshouses or “poor farms,” as they were often called, also opened during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in rural areas, including Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties. Countryside institutions became necessary as cities passed poor laws specifying that the infirm and impoverished seeking aid could only obtain it from the county in which they had legal residence. Although industrialization drew many individuals seeking jobs to cities, those who fell on hard times had to be transported back to their hometowns. Rural almshouses differed somewhat from their urban counterparts by placing greater emphasis on being self-sufficient institutions and assigning work centered on farming and related tasks.

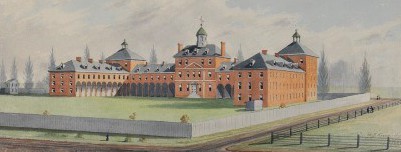

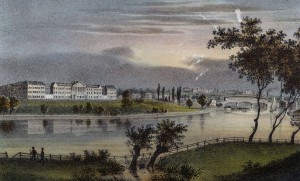

Meanwhile the Bettering House, thought to be the solution to eliminating Philadelphia’s poor population, fell to the same corruption, lack of funding, and overcrowding as the city’s first almshouse and closed in 1835. The same year, its replacement opened. With this next iteration of the Philadelphia Almshouse, founders hoped to succeed by completely institutionalizing the poor. Located in West Philadelphia in an area formerly known as Blockley Township between Thirty-Fourth Street and Cleveland Avenue (later renamed University Avenue), the new “Blockley Almshouse” had no formal gardens. It looked out over the Schuylkill River, which served as an effective barrier between the city and its poor. A massive complex of four main buildings, Blockley included a traditional poorhouse, insane asylum, infirmary, and orphanage. Showing off industrious paupers was no longer of importance. All activities occurred privately within the compound, including numerous dissections of bodies of deceased inmates by doctors and their anatomy students. With a well-developed infirmary to treat the sick poor, Blockley Almshouse evolved into the Philadelphia General Hospital in 1919. Similarly, by the 1960s many of the surrounding rural almshouses were converted to nursing homes.

The almshouses’ role as free hospitals for the sick indigent may be their most positive legacy. The first Philadelphia City Almshouse essentially served as the first public hospital in the colonies. Almshouses did not turn away those with ailments viewed as “sinful,” such as venereal diseases or complications from alcoholism. For ailing prostitutes and unwed pregnant mothers, the almshouses were often the only choice available. Many doctors in the Philadelphia area learned their trade from practicing on inmates. That being said, almshouses were institutions of last resort for many who turned to them during difficult times. The use of almshouses and the practice of institutionalizing the poor ended throughout the United States in the mid-twentieth century after three centuries of failed policy.

Mara Kaktins is a historical archaeologist who holds an M.A. from Temple University. Her graduate work focused on the changing treatment of the poor throughout the colonial period. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Pennsylvania programs for welfare-to-work push job seekers, but offer less support (WHYY, May 8, 2012)

- Name change again under consideration for Pa. Department of Public Welfare (WHYY, March 15, 2013)

- With Corbett's approval, Pa.'s Public Welfare getting new moniker (WHYY, September 21, 2014)

- Explainer: How New Jersey's welfare program works (WHYY, February 23, 2016)

Links

- Paupers and Poor Relief: Studying the Poor in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (Department of Records)

- The Bettering House (Free Library of Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: Philadelphia General Hospital (Old Blockley) (Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Blockley Almshouse (Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network)

- Blockley: The Memory Lingers On (University City Historical Society)

- History of the Philadelphia Almshouses and Hospitals (1905) (Archive.org)

- Pennsylvania Welfare Services (Pennsylvania Department of Human Services)

- New Jersey Welfare Services (New Jersey Department of Human Services)