Occupy Philadelphia

By John E. Smith III | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

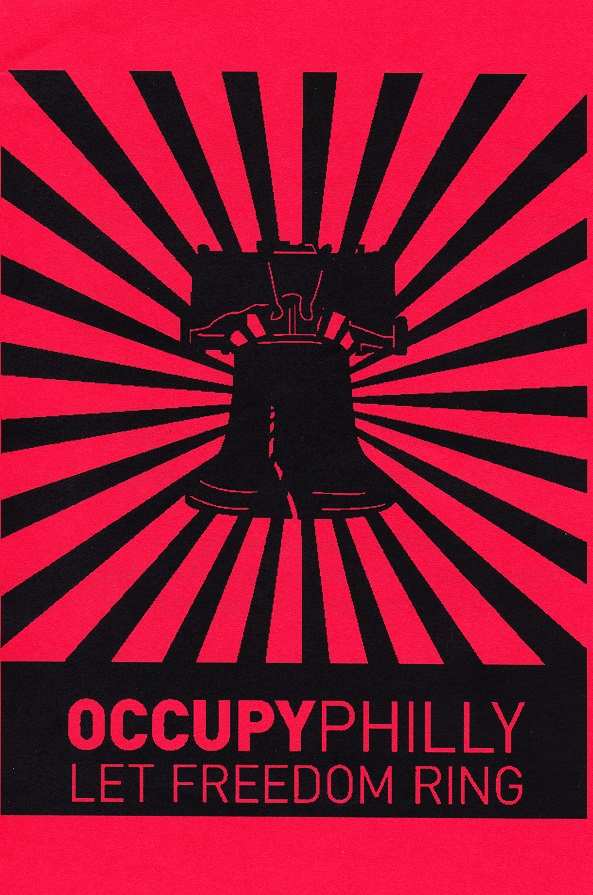

For fifty-six days between October 6 and November 30, 2011, local activists participated in Occupy Philadelphia—a leaderless, decentralized movement against social and economic inequality. Their action joined an international wave of dissent against political and economic corruption that ranged from anti-austerity protests in Europe to the Arab Spring demonstrations throughout North Africa and the Middle East. Occupy movements in cities across the globe united protesters and inspired change.

In Philadelphia, the Occupy movement unofficially began on September 29, 2011, when a general assembly of activists gathered at the Arch Street United Methodist Church. A few days later on October 4, a second meeting attracted an even larger crowd to plan a protest similar to the ongoing, nearly month-long Occupy Wall Street demonstration in New York City’s Zuccotti Park. At the meeting, the group determined where and when to begin the occupation of a public space in Philadelphia. Possible locations included Love Park, Rittenhouse Square, Independence Hall, and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. After much discussion, the group agreed to begin the demonstration on October 6 at Dilworth Plaza adjacent to City Hall—the epicenter of Philadelphia’s political bureaucracy.

Occupy Philadelphia transcended age, race, religion, and political affiliation, and this diversity generated incoherent messages, as some protested against corporate greed, bank bailouts, big money’s influence on elections, and other economic injustices while others protested police brutality, foreign wars, and social conservatism. Although many joined the movement for vastly different reasons, collectively the group identified as “the 99 percent.” They argued that a disproportionate 1 percent of the population controlled the majority of political power and wealth. While some opponents criticized the group’s lack of specific goals, members emphasized the movement’s ability to unite dissimilar political factions and rally around a broader message.

Tent City at City Hall

A city of tents occupied Dilworth Plaza on the west side of City Hall for eight weeks as Occupy Philadelphia activists executed their public protest with no anticipated end date. The camp included a first-aid station, library and education center, food station, and meeting areas for various subcommittees. Over time, the camp attracted the participation of many of the city’s homeless population and raised public concern regarding crime and sanitation.

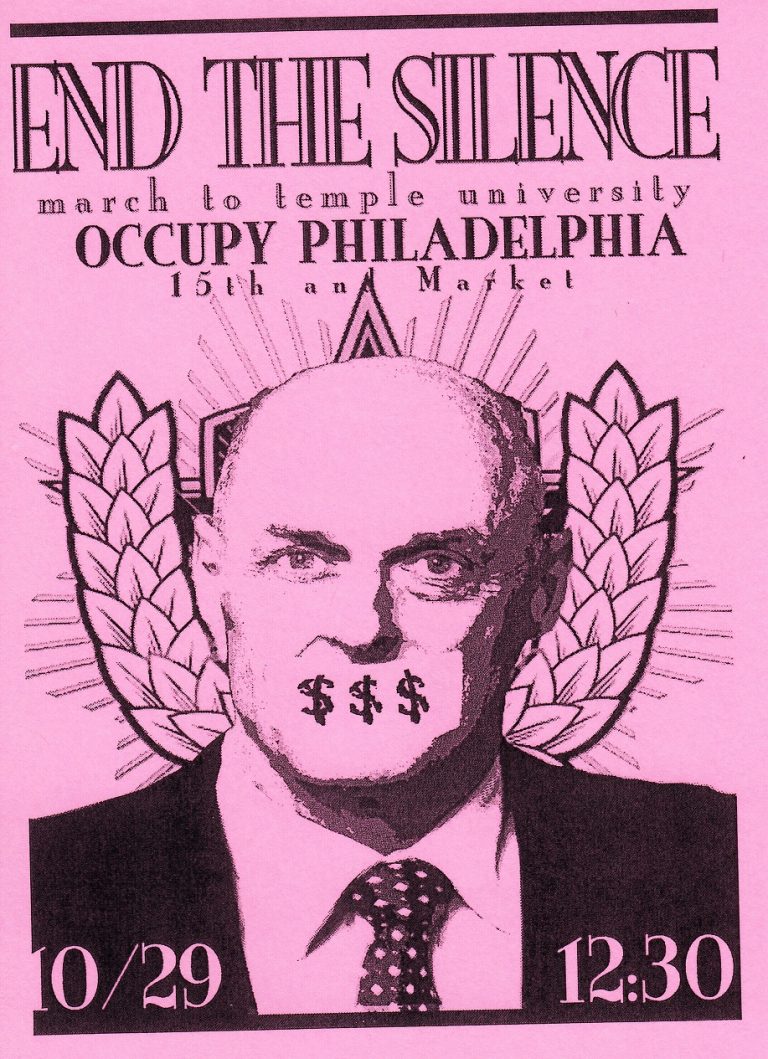

Throughout the occupation, demonstrators practiced peaceful, nonviolent protest methods including chanting slogans, raising signs, and practicing civil disobedience. Many felt empowered to join the movement because of the support from the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Lawyers Guild, who led “Know Your Rights” trainings during the early days of the occupation. The group organized several marches across the city to parade their strength in numbers to locations including to the Liberty Bell, Wells Fargo, the Comcast Center, and the Rittenhouse Hotel where Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney (b. 1947) held a fundraising event. On October 21, U.S. House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (b. 1963) of Virginia canceled a scheduled talk at the University of Pennsylvania when protesters announced plans to rally outside Penn’s Huntsman Hall in an event dubbed “Occupy Cantor.”

Occupy Philadelphia attracted the attention of both local and national progressive leaders who spoke in support of the movement. Visitors to the encampment included scholar-activist and author Angela Davis (b. 1944), City University of New York Professor Frances Fox Piven (b. 1932), and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson (b.1941). Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957), who was up for reelection on November 8, 2011, expressed support throughout the occupation, stating that he too identified as the 99 percent. Despite the endorsement, many Occupy protesters questioned whether the mayor served as a genuine ally or simply offered his sympathies to avoid becoming a target. Opponents criticized the mayor’s legislative track record and suggested his policies did not align with his public statements. They pointed specifically to Nutter’s cuts to education and public services like libraries, pools, recreation centers, and the Fire Department.

Dispersal Ordered

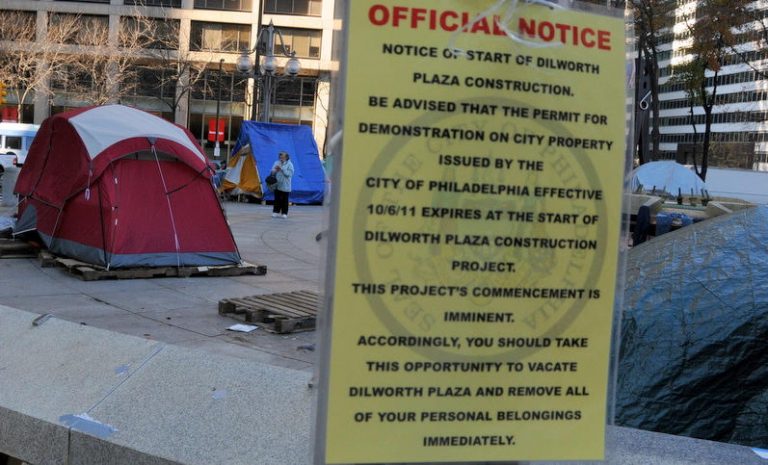

On November 15, city officials posted public notices throughout the encampment ordering protesters to evacuate Dilworth Plaza so a previously planned $50 million renovation project could commence. Unsure of when the police would raid the camp, anticipation grew and many of the occupiers dispersed. Two weeks later, in the early morning hours of November 30, Philadelphia police evacuated the Occupy Philadelphia encampment using heavy equipment to remove the remaining debris. Lingering protestors trekked around Center City until 5 a.m., when police arrested around 50 people on charges including obstruction of a highway, failure to disperse, and conspiracy (most were later acquitted on all charges). At 7 a.m., Nutter spoke with the media and declared the occupation “over.”

Although Occupy Philadelphia failed to produce direct legislation, it helped introduce economic inequality into a broader political discourse. The widening gap between rich and poor became a major talking point during the 2012 presidential election. Locally, the 2011 Occupy Philadelphia movement mobilized progressive activists and prepared them for future protests, including demonstrations following the 2016 presidential election and the 2018 “Occupy ICE” protest at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency’s office in Philadelphia. Occupy Philadelphia may have only lasted for a few weeks in the fall of 2011, but the movement’s ideas and messages remained relevant in shaping Philadelphia’s image as a progressive American city.

John E. Smith III is a 2018 graduate from Temple University’s Center for Public History. He is the Assistant Archivist at the Chester County Archives in West Chester, PA. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Occupation Begins (hiddencityphila.org)

- Game Change at Occupy Philly (hiddencityphila.org)

- Occupy Philly Archives (Temple Libraries' Blog)

- Occupy Philly Archives (Philadelphia Magazine)

- Occupy Penn Statement of Principles (The Daily Pennsylvanian)

- Dilworth Plaza Through the Years (Philly History Blog)