Black Lives Matter

Essay

Black Lives Matter (BLM) as an organization and a movement came to public attention after the deaths of two young Black men, Trayvon Martin (1995-2012) in Sanford, Florida, and Mike Brown (1996-2014) in Ferguson, Missouri. A Philadelphia chapter of the decentralized, nonhierarchical movement officially formed in May 2015. With direct ties to earlier civil rights era organizations, the movement has continued the Black freedom struggle against systemic racism and anti-Black violence, and its manifesto echoed the politics of Black Feminist groups like the Combahee River Collective and the Third World Women’s Alliance. Within a decade, Black Lives Matter grew from a social media hashtag to a movement estimated between fifteen million and twenty-six million people in the United States alone by 2020, when worldwide protests responded to the murder of another Black man, George Floyd (1973-2020), in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The movement began in 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman (b. 1983), a white vigilante, for the killing of Trayvon Martin. Three Black women, Alicia Garza (b. 1981), Patrisse Cullors (b. 1984), and Opal Tometi (b.1984), originated the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on social media. The hashtag initiated protests the next year following the killings of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner (1970-2014) in New York City at the hands of police officers. Subsequently, between 2014 and 2016 Black Lives Matter exploded into a national network of organizations, including the Black Lives Matter Global Network, the Dream Defenders, and the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, among many others. In August 2014 organizers in St. Louis issued a call for Black activists to take part in the Black Life Matters Freedom Ride. Started by Cullors, this ride took place on August 28 when about thirty activists from New York, Philadelphia, and New Jersey traveled by bus from New York City to Ferguson, Missouri, and attended ongoing protests there.

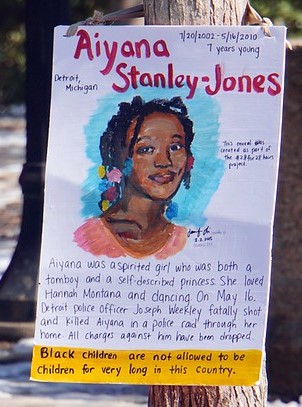

Philadelphia’s chapter of Black Lives Matter formed through the work of community activists Azsherae Gary (b.1988) and Taylor Johnson-Gordon (b.1988) in 2015. The first meeting, in May, focused on the initiatives of abolition of police and educational justice. The local group also supported the #AiyanasDreams annual campaign, named after seven-year old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, who died at the hands of the Detroit Police Department Special Response Team on May 16, 2010. The campaign emphasized that although Black women and girls constituted only 13 percent of the population, they made up a third of police killings of all women.

The George Floyd Protests

In 2020, in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, the Philadelphia chapter of BLM led mass protests that resulted in multiple clashes with police and numerous arrests. Philadelphia police, often clad in riot gear, arrested over two hundred people on May 30, the majority for breaking a city-imposed curfew or failing to disperse. On June 1, police responded to marchers on the Vine Street Expressway with pepper spray and tear gas. Similar to protests in New York City and Portland, Oregon, officials in the city brought in the National Guard to quell protests. In June 2020, BLM Philly and eleven other organizations in the Black Philly Radical Collective, announced thirteen demands to the city of Philadelphia. They wanted police departments defunded and abolished, the release of political prisoners, and economic justice, among other demands. The American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania later criticized the police response in Philadelphia as “overwhelming, racially-targeted, and excessive,” and subsequent lawsuits cost the city settlements totaling $9.25 million.

BLM protests during the summer of 2020 also sparked calls to remove statues in several American cities on the basis that the monuments represented an erasure of the harm done by white supremacy. In Philadelphia, protesters tried to topple the statue of former Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91). A former police commissioner, to many Rizzo represented a legacy of racial intolerance and oppression tied to past police violence, his call for Philadelphians to “vote white” in the 1970s, and the 1978 police standoff with the Black liberation group MOVE. Efforts to remove the Rizzo statue began in 2017, but it was not taken down until June 2020. Black Lives Matter actions that year also included murals painted in cities with historic Black communities. In Camden, New Jersey, a mural painted on Broadway covered four blocks of the city. The momentum from the summer of protests also hastened placement of a marker at Cooper Poynt commemorating a site where enslaved Africans were bought and sold.

The Camden Scenario

While BLM Philly protested in their city and were met by police in riot gear, in Camden Police Chief Joseph Wysocki (b. 1970) marched with protesters over the murder of George Floyd. This reflected changed police-community relations forged in Camden during the previous decade. The city had a long history of community organizing amid an ineffective relationship with police. In 1967, Charles “Poppy” Sharp (1932-99) founded the Black People’s Unity Movement, which tackled the power structure and police brutality in the city. Elmer Winston (1925-2006) helped found and run the Camden Neighborhood Renaissance Organization. Camden residents, many of them elderly, formed block patrols, challenged drug dealers, and improved their community on their terms. In 2012, when murder rates were eighteen times the national average and scores of excessive-force complaints were lodged against police, the residents, City Council, and mayor joined together to dissolve the Camden Police Department and replace it in 2013 with a countywide department. Homicides decreased from sixty-seven in 2012 to twenty-five in 2019, with only three excessive force complaints in 2020.

The results of Camden’s new policing system predated the Black Lives Matter movement but came to the forefront during BLM protests in 2020 amid calls to defund the police. Camden showcased an example of how community-led policing could change a city’s trajectory in the wake of a worldwide reckoning with police brutality and anti-Blackness.

Gwendolyn Fowler is a Ph.D. student at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, where she studies African American and Women’s and Gender History. Her research focuses on the welfare rights movement in the United States. She is currently researching the Westside Mothers of Detroit, Michigan. Her dissertation is titled, tentatively, “Without Mother You’d Have No People: Mother Power and Welfare Rights in the Motor City.” (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University