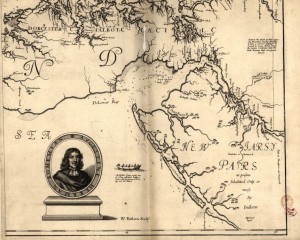

West New Jersey

Essay

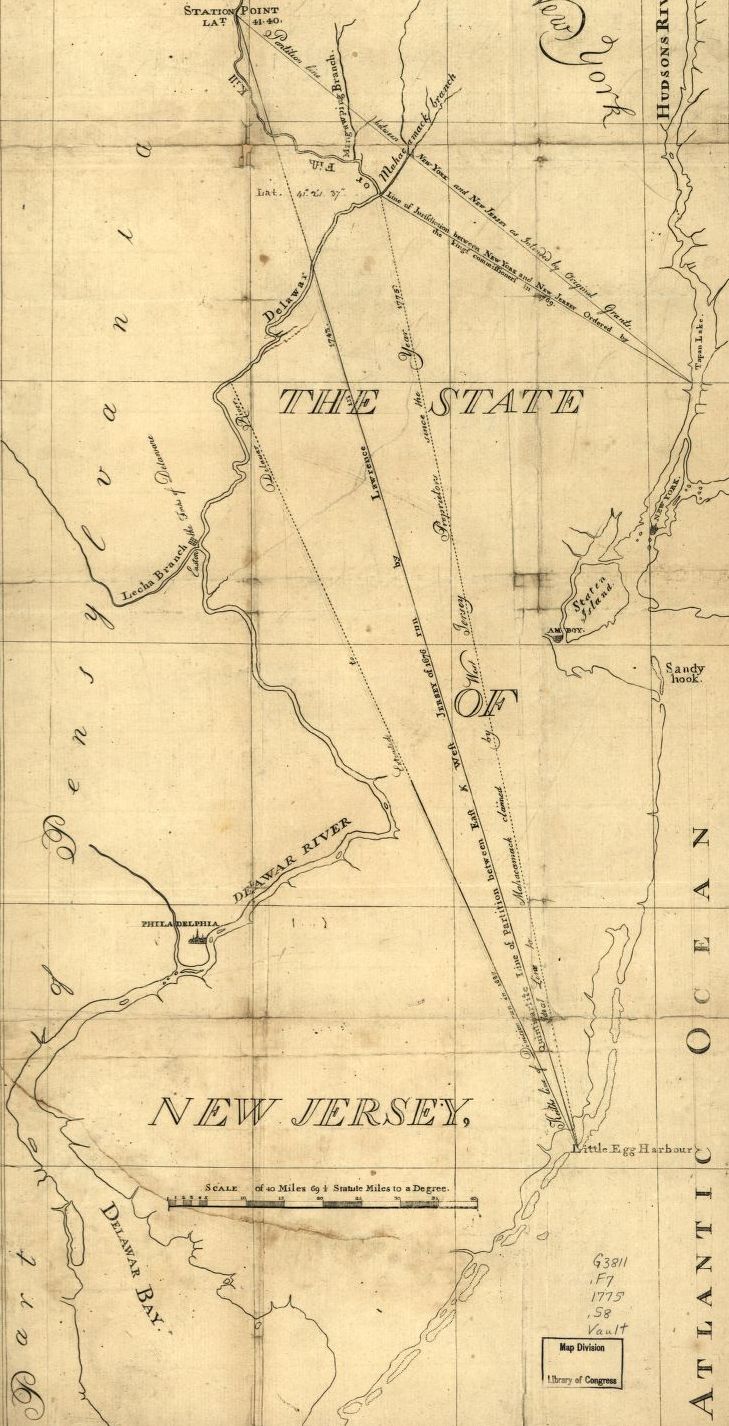

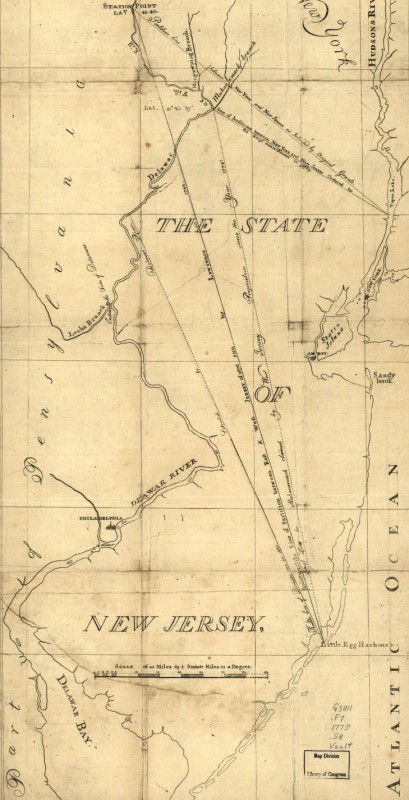

Between 1674 and 1702, New Jersey was divided in half: The proprietary West Jersey colony faced the Delaware River while East Jersey looked toward the Hudson. Although this political division lasted less than three decades, it represented long-standing geographical orientations of the Lenape and Munsee native inhabitants and European colonists. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) reputedly called New Jersey “a barrel tapped at both ends,” a productive countryside exploited by Philadelphia and New York. While West New Jersey quickly came within Philadelphia’s economic orbit, the region nonetheless retained a distinct political and social identity.

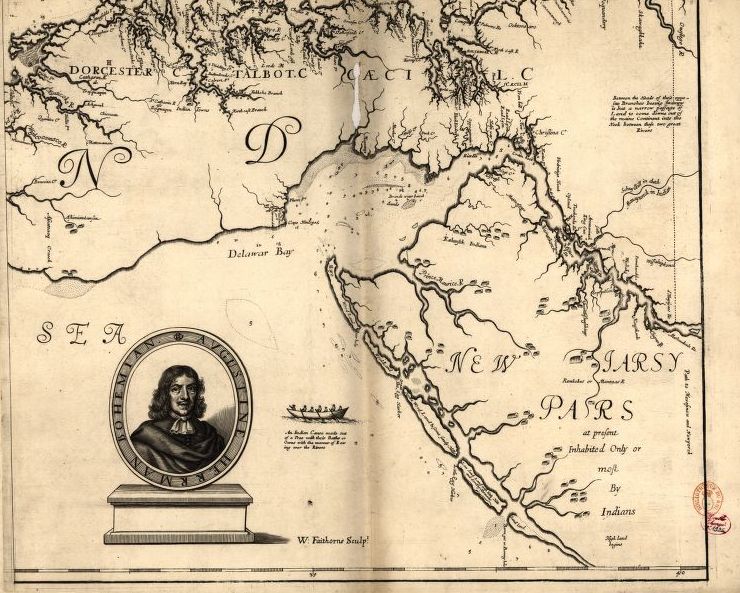

Native Americans lived in the Delaware Valley at least 10,000 years before the Dutch, Swedes, Finns, and English arrived in the seventeenth century. The Lenapes, who controlled southern and western New Jersey, lived in autonomous towns along creeks leading to the Delaware River and along the Atlantic coast near Delaware Bay. Some Lenape peoples, such as the Armewamese and Cohanseys, possessed land on both sides of the river in what are now Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. Because Lenapes traveled frequently by canoe, they viewed rivers and streams as highways rather than obstacles.

Prior to the founding of West New Jersey in 1674, European population in the region remained sparse. A small Dutch settlement on Matinicum (now Burlington) Island lasted only from 1624 until 1626 when, on a site across the river from current Philadelphia, Dutch traders established Fort Nassau. A group of New Englanders in 1641 obtained the Lenapes’ permission to colonize several Delaware Valley locations, one at Varkens Kill (now Salem Creek). Dutch opposition and disease destroyed the colony; a small remnant of English settlers became part of the population of New Sweden, which existed from 1638 to 1655 primarily on the west bank of the Delaware. The Dutch conquered New Sweden in 1655 and held the Delaware colony until 1664, when English forces of James, Duke of York (1633-1701) took control. A few Dutch and French colonists moved to southwestern New Jersey in the late 1660s, purchasing land from the Lenapes. A few years later, Swedish and Finnish settlers followed suit, departing from the west bank of the Delaware River in rebellion against English land policies, including assessment of quitrents and expropriation of common lands.

The Colony of New Jersey, 1664

The English king Charles II (1630-85) initiated the proprietary colony of New Jersey in 1664 when he granted his brother James, Duke of York the rights of proprietorship, including the power to govern and ability to own and sell land. The duke in turn granted New Jersey to Sir John Berkeley (1602-78) and Sir George Carteret (c. 1610-80). In 1674, the proprietorship of New Jersey was divided in half, with Berkeley taking West New Jersey, which he promptly sold to John Fenwick (c. 1618-1683) in trust for Edward Byllynge (c. 1623-1687). When the English Quakers Fenwick and Byllynge quarreled, three Quaker trustees, including William Penn (1644-1718), mediated the dispute. Adding to these difficulties, the Duke of York refused to transfer the power to govern West New Jersey to the Quaker proprietors.

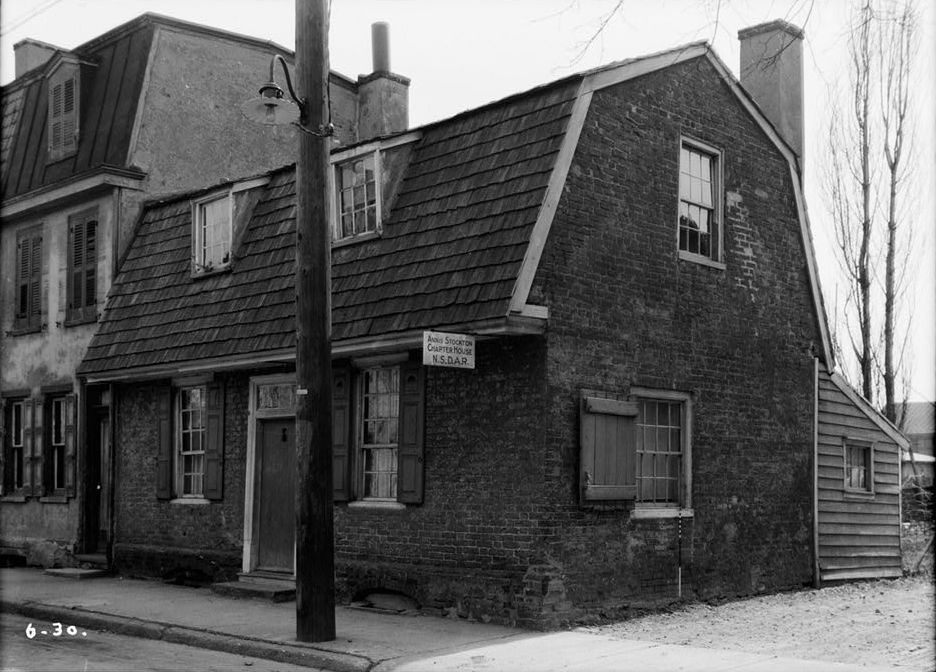

Complicated financial deals and lawsuits arising from the dispute between Fenwick and Byllynge resulted in two initial Quaker settlements in West New Jersey: Salem, founded in 1675, and Burlington in 1677. Fenwick demanded one-tenth of the West New Jersey proprietorship to launch his own settlement, which conflicted with the intentions of Byllynge and the trustees for a unified colony. Byllynge wanted to give Fenwick his tenth in scattered places across West New Jersey, but instead, without Byllynge’s assent, Fenwick took his one-tenth in a single location, which he called Salem, and sold 148,000 acres to about 50 purchasers. The Quaker colonists arrived in southern New Jersey in 1675, entering a country dominated by Lenapes where some Europeans, mostly Swedes, Finns, and Dutch, had settled during the previous decade. Fenwick promptly purchased land from the Lenapes of the region—the Cohanseys—with whom he maintained good relations. Land conveyances of 1675 and 1676 specified that Fenwick would receive territory, “excepted always … the plantations in which [the natives] now inhabit,” in return for cloth, rum, guns, and other items.

Despite these conveyances, Salem’s status remained insecure because Fenwick, as a result of financial difficulties and legal challenges, lacked English title, deeds, and the right to govern. Governor Edmund Andros (1637-1714) of New York, who for the Duke of York until 1680 claimed authority over both banks of the Delaware, jailed Fenwick in New York for two extended periods, leaving the land claims of the Salem colonists unclear.

The West New Jersey Concessions

In 1676, the Quaker trustees and Edward Byllynge implemented plans for settling the other ninety percent of West New Jersey. Byllynge probably drafted the innovative West New Jersey Concessions (1676) that described the process for distributing land, granted religious freedom and trial by jury, and set out a plan for mediation of disputes between Lenapes and Europeans. Male property owners resident in West New Jersey would annually elect a general assembly by putting balls into ballot boxes rather than by “the confused way of cries and voices” that was common in other places. The Duke of York delayed implementation of the Concessions by not transferring until 1680 the right of government to Byllynge, who then renounced the Concessions by becoming governor, an office not included in the document. Nevertheless, though the Concessions failed to become the official West Jersey constitution, the document suggests the ideals of the colonists who signed it. Many provisions of the Concessions, including the elected assembly, religious freedom, and trial by jury, became West New Jersey law.

In 1677, Byllynge and the trustees sent the ship Kent with 230 Friends to establish the Burlington colony, appointing nine commissioners to govern until an assembly could be elected. When the Kent stopped first to inform Andros of their plans to settle, he denied liberty to the Quakers to establish their own government, but agreed to appoint the trustees’ commissioners as magistrates to report to him. Andros also charged the passengers duties on their cargo, creating considerable ill-will. In response to appeals from Byllynge and the trustees, in 1680 the Duke of York transferred the right of government to Edward Byllynge, ending the customs fees and meddling of the New York government. An estimated 1,760 Friends settled in West New Jersey by 1682, but after that date most Quaker immigrants accepted William Penn’s invitation to settle his new Quaker colony of Pennsylvania.

The Swedes, Finns, and Lenapes offered the Burlington colonists assistance despite worry about their increasing numbers. The Swedes and Finns provided shelter soon after the Kent arrived and helped the West Jersey commissioners acquire land from the Lenapes. The winter of 1677-78 came before the new settlers could begin constructing Burlington, so they built wigwams like the Lenapes’ and depended upon the natives for corn, vegetables, venison, fish, and fowl. Unfortunately the Burlington colonists brought smallpox that, like earlier epidemics, killed many Lenapes.

Autonomous Communities

During the proprietary period from 1674 to 1702, the West New Jersey colonists organized themselves much like their Lenape neighbors—in autonomous communities governed by local officials, loosely affiliated with neighboring colonial and native settlements. Byllynge and the trustees founded Burlington as the seat of West New Jersey government, but county courts in Burlington, Salem, Gloucester, and Cape May provided stability during the proprietary years. Centralized government from Burlington was impossible because of the distance between small dispersed settlements and because contested land claims, power struggles, and the English government’s efforts to repeal the proprietorship created a power vacuum at the top.

The county courts, as demonstrated by their minutes, provided effective government by punishing crime, hearing disputes, and collecting taxes for roads, bridges, and public buildings. A murder case in Salem in 1691-92 provides one example of how the local magistrates sustained government despite chaos at the provincial level. The Salem court tried and executed a carpenter Thomas Lutherland (c. 1652-92) though only the provincial government, not county courts, had legal authority in capital cases. Rather than wait until the provincial government reorganized, the Salem justices took the power to execute a murderer into their own hands because they believed Lutherland was dangerous and would escape jail.

Although Quakers, including William Penn, founded both West New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the colonies evolved differently in their initial years. In West New Jersey, the continuing power of the Lenapes, smaller European population, and lack of unified leadership in Burlington created more room for local autonomy and intercultural alliances between natives and colonists than in Pennsylvania, where larger numbers of immigrants and a more hierarchical government held sway. Even so, the two provinces developed close economic ties, as Philadelphia’s growth quickly attracted business with West Jersey merchants and farmers, thus continuing a partnership between both sides of the Delaware River.

Dissolution of West New Jersey Colony

The proprietary colony of West New Jersey dissolved in 1702 when the proprietors of both East and West New Jersey surrendered their right of government to the English Crown. The proprietors were under numerous pressures, including charges that the colonies were ungovernable, factionalized, and defiant against imperial rule. Though English administrator Edward Randolph (1632-1703) suggested that “the country is too large, and the inhabitants too few to be continued a separate government, therefore East Jersey ought to be annexed to New York and West Jersey to Pennsylvania and the three lower counties,” the Crown decided on the unified province of New Jersey. The assembly of twenty-four members, equally divided by section, would rotate meetings between Perth Amboy and Burlington. The governor of New York, Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury (1661-1723) assumed office as the first New Jersey royal governor in 1703.

Jean R. Soderlund is a Professor of History Emeritus at Lehigh University. She is author of Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn (2015) and is currently researching a social history of colonial West Jersey. (Author information cureent at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Burlington County Historical Society

- Salem County Historical Society

- The City of Burlington Historic District

- The West Jersey Proprietors Rule Historical Marker (HMdb.org)

- New Jersey State Museum (State of New Jersey: Department of State)

- Colonial Charters, Grants, and Related Documents (Yale University: Lillian Goldman Law Library)

- West Jersey History Project

- Separate Paths: Lenapes and Colonists in West New Jersey (2022)