Delaware Bay

Essay

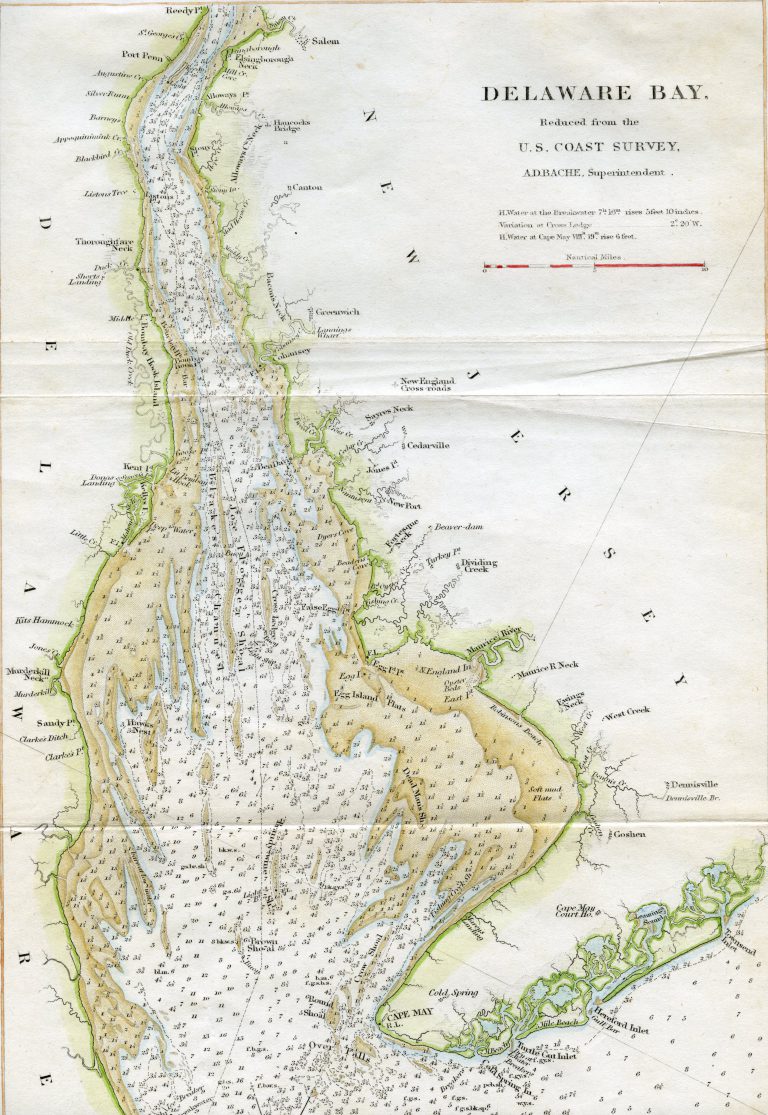

The Delaware Bay does not often get the historical acknowledgement received by its estuarine neighbor, the Delaware River, but it exerted equal weight in shaping the Philadelphia region’s cultural and economic development. Over seven hundred square miles in size and bordered by New Jersey and Delaware, the Delaware Bay is one of America’s premier maritime gateways, connecting the Philadelphia region to both international and domestic trade. While the bay’s extensive salt marshes, along with limited sheltered harbors, prevented certain economic and military uses, its natural resources duly compensated for these environmental obstacles. The bay’s waters fostered an array of navigational skills among shoreline residents, a tradition that would later pay dividends when sail and steam transport expanded in the nineteenth century. Stands of timber lining the bay’s shoreline and tributaries facilitated the growth of shipbuilding, an industry that flourished until almost the end of the twentieth century. Most notable, the use of the bay’s marine resources—from its well-known oysters to salt hay—formed the backbone of its economic fortunes for the four centuries following European contact.

Taking note of what was already apparent to local Native American populations, colonial observers envisioned the bay’s far-reaching potential. Referring to the Delaware Bay as part of a “Terrestrial Canaan,” a 1676 promotional broadside for West New Jersey singled out the bay’s “great numbers of Sturgions, Lobsters, Oysters, and many other Sea-Fish,” as well as its capacity to serve as a gateway for natural resource use “a hundred Miles into the Country.” William Penn (1644–1718) cast the Delaware Bay and its resources as an organizing agent of Philadelphia’s regional dynamics and the city’s rise as an international entrepôt.

Following the pattern of the Dutch and Swedes who preceded them, English settlers continued the practice of harvesting the Delaware Bay’s rich stores of fur-bearing animals and coordinated these activities with trade among the Lenape Indians. But being intent on permanent settlement, the British instituted the commercial use of the bay’s waterborne and terrestrial resources. Wider consumption of shellfish (oysters, clams) and finfish (shad, sturgeon, rockfish) raised concern over the sustainability of these stocks enough to prompt New Jersey to enact in 1719 one of the first laws in America regulating the use of natural oyster beds.

Soils along the bay’s shore were not as fertile as those along the Delaware River, but some areas did produce profitable yields of grain crops and corn, and farmers working along the Delaware Bay and its tributaries during the colonial and early national periods availed themselves of vessel transport afforded by this estuarine system. The environs around Greenwich, New Jersey—which straddled the colony/state’s inner and outer coastal plains—was most notable in this regard, and Greenwich emerged as the Delaware Bay’s most prominent eighteenth-century port and supplier to Philadelphia..

Amid these agricultural developments, construction of earthen dikes and banks enabled farmers to reclaim tidal marshes and meadows, transforming the bay’s shoreline. Once drained, these banked meadows allowed efficient harvesting of cordgrass, provided grazing for livestock and sheep, and, when sufficiently relieved of prior salt water content, could be used to raise a variety of crops. The bay’s moderate climate allowed colonial settlers—particularly those who arrived from New England’s colder temperatures—to pasture animals at longer monthly intervals in salt meadows and reclaimed tidal lands.

Shallops and flatboats brought agricultural commodities from the bay shore to Philadelphia, as well as a variety of products derived from the region’s timber supply. Eighteenth-century newspaper accounts and wills from the Delaware Valley highlight the importance of woodlots, particularly important in bay shore areas where soil conditions hindered profitable agriculture. Among those who prepared timber for market were the area’s Swedish and Finnish settlers. Having brought their well-known woodman’s skills to the New World, they were conspicuous participants in the Delaware Bay region’s wood economy. Delaware Bay residents harvested merchantable cordwood for export to Philadelphia and provided other wood products such as barrel staves, ship planking, naval stores (tar, pitch), and charcoal. The bay region’s impressive stands of Atlantic white cedar provided valuable roof shingles and house sheathing as well as material for boatbuilding, a regional tradition that endured until the end of the twentieth century.

While agriculture and wood harvesting carried forward into the nineteenth century, joined by an increasing emphasis on truck farming that continued into the twentieth century, the economic ambitions gripping the Philadelphia region transformed the use of the bay’s waters. Central to these commercial and industrial goals was the need to move commodities, particularly in bulk, to and from Philadelphia through the Delaware Bay to points all along the East Coast of the United States. The Navigation Act of 1817 limited such shipping, known as the coastwise trade, to American-flagged vessels. Duly incentivized by shipping demand and legal protections, bay shore residents from New Jersey and Delaware built, crewed, and owned coastal schooners (principally two- and three-masted). Experienced in working the water, they seized on the opportunities presented by this emerging maritime economy.

Arguably the Delaware Bay’s most significant tributary, New Jersey’s Maurice River sported a robust schedule of coastal schooner and barkentine construction between the 1830s and 1880s. An important 1882 survey of U.S. shipbuilding by Henry Hall (1845–1920) showed the Maurice River towns of Mauricetown, Dorchester, and Leesburg were the beneficiaries of these activities and singled out Mauricetown as “being dependent on building [vessels] and navigation [coastwise trade]” with “50 to 60 sea captains living in the place, [where] almost everybody owns shares in vessels.”

These same economic ambitions ultimately impacted the Delaware Bay’s most valuable marine resource—the oyster. Well-established as a culinary staple throughout the Delaware Bay/River corridor—from Philadelphia’s finest dining rooms to an array of oyster bars and cellars serving ordinary citizens—New Jersey stood ready to exploit the market potential of its rich oyster beds. Legislation in the mid-nineteenth century authorized the transplanting of seed oysters from natural spawning areas to barren bay bottoms privately leased from the state. Oystermen found that transplanting oysters to the higher salinity levels of Maurice River Cove improved growth, enhanced the quality of their meats, and offered greater control in cultivating their product for market. When ready for market, schooners and sloops transported oysters to Philadelphia.

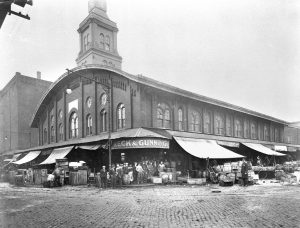

The arrival and improvement of rail connections along New Jersey’s Delaware Bay shoreline, from the 1870s through the early 1900s, dramatically transformed the oyster industry and attracted unprecedented levels of investment from throughout the region. The West Jersey and Seashore Railroad (WJSR), a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CRRNJ) financed the construction of modern shipping facilities at, respectively, “Maurice River” on the eastern side of the Maurice River and at “Bivalve” on the river’s western side. Servicing far-flung markets from rail connections in Philadelphia and New York City, these facilities helped drive an ever-increasing volume of oyster harvests. Each of these multiunit facilities teemed with activity as workers bagged, barreled, and shipped oysters and, eventually, removed them from their shells and canned them in new shucking houses. This work linked Philadelphia’s commission merchants and restaurateurs—many of whom operated from the city’s Dock Street Market—to vessel captains, policy makers, and scientists, as well as to African Americans who arrived from the Chesapeake to work on oyster boats and as shuckers. All this activity reflected the oyster industry’s one-time status as the economic bedrock of the Delaware Bay region with its inextricable ties to Philadelphia.

New transportation methods also transformed the Delaware Bay’s shad and sturgeon fisheries. Each species returned to its natal grounds to spawn in the spring, a ritual that energized a number of small communities on the New Jersey and Delaware sides of the bay. Of all these fishing sites, Bayside—outside of Greenwich—was arguably the most prominent due to CRRNJ rail connections linking it to Philadelphia and New York markets. The combination of shad and sturgeon skiffs, floating cabins, and shoreside processing buildings defined this amphibious extension of Philadelphia’s economic sphere. But neither fishery was immune from overfishing and pollution. When sturgeon fishermen met in Philadelphia around 1900 to organize the Sturgeon Fishermen’s Protective Society, it was too late to stem the tide of depletion. The combined effect of pollution and fishermen unwilling to curb their catch meant that the sturgeon fishery—once plentiful enough to allow people to affordably purchase caviar sandwiches—was in the midst of its final days.

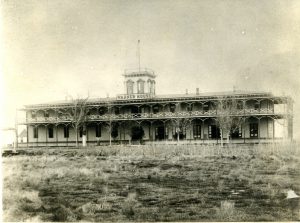

Rail and steamship service operating from Philadelphia opened the Delaware Bay to recreational activity during the second half of the nineteenth century, and this trend continued in the twentieth as automobiles further democratized leisure pursuits. Hotels, such as the Warner House at the confluence of the Delaware Bay and New Jersey’s Cohansey River, were emblematic of this enthusiasm and accommodated visitors from throughout the mid-Atlantic region and beyond. But smaller guesthouses and cottages were more the norm. By the late nineteenth century, Fortescue, New Jersey—centrally located on the Delaware Bay—epitomized the modest accommodations that typified vacation life along the bay. Some visitors swam, others engaged in recreational fishing and crabbing, while others simply sat on the beach and gazed at the bay’s glistening waters. The bay shore’s plentiful waterfowl and shore birds attracted hunters from Philadelphia’s most prominent social circles, and they frequented plush accommodations such as the Sora Gun Club on the Cohansey River. Thomas Eakins’s (1844–1916) paintings of hunting scenes on the bay brought national attention to these activities and, in turn, fostered interest from the Philadelphia Sketch Club, the Philadelphia Watercolor Society, and a host of documentary photographers and writers motivated by the region’s local color. The Delaware Bay inspired participants of the nature study movement, including writer Dallas Lore Sharp (1870–1929), a Delaware Bay native whose rise to national prominence was grounded in experiencing the bay’s natural endowments. The cumulative effect of cultural and environmental commentary laid the foundation for conservation of the bay’s tidal marshes throughout the twentieth century, as well as promoting the roots of ecotourism at birding sites whose reputation garnered international fame.

When, in the early nineteenth century, federal and state authorities began planning the implementation of modern navigational aids in the Delaware Bay and along its shorelines, they unabashedly signaled this estuarine system’s critical role in advancing the fortunes of the greater Philadelphia area. The city’s status as America’s largest freshwater port underscored the urgency of these measures, and the Delaware Bay became a crucible for some of the nation’s most important developments in lighthouse technology and a focal point of work conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Anchored to the bay’s floor, channel lights at Brandywine Shoals (1850), Fourteen Foot Bank (1885), Cross Ledge (1877/78), Miah Maull Shoal (1909), and Ship John Shoal (1877) epitomized the environmental dominion and economic ambition that drove these engineering measures. Joining these channel lights were a collection of shoreline lighthouses whose appearance conformed to regional vernacular building idioms in New Jersey and Delaware. These navigational aids form a technological backdrop of longstanding challenges that have confronted the Delaware Bay, such as biological invasions—most notably oyster diseases MSX (haplosporidium nelsoni) and dermo (Perkinsus marinus).

This technological context has been central to historical debates over the effects of water diversion farther up the Delaware Estuary and ecological concerns surrounding the dredging of a deeper ship channel and barge traffic on the bay’s tributaries. Passage of federal legislation in the 1880s made dredging a focal point of efforts to improve the navigability of the Delaware Bay and River. While deepening the channel allowed larger vessels greater access to Philadelphia, it also punctuated the environmental cost of accidents (oil spillage, fires) involved in such shipping. Deepening the bay and river channel also raised the possibility of elevated salinity levels farther up the estuary and the potential ecological toll of changes in its water chemistry.

Starting in the 1950s, modern environmentalism reframed the utopic vision of the Delaware Bay cast by European settlers four centuries earlier. By the dawn of the twenty-first century, the Delaware Bay was still an ever-present backdrop of economic ambitions driving redevelopment of the Port of Philadelphia, along with similar initiatives at ports in Salem, Paulsboro, Gloucester, and Camden, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware. With intermodal shipping now firmly ensconced in Philadelphia’s economy, the Delaware Bay’s shipping lanes assumed renewed importance in regional planning. But greater environmental consciousness contributed to revised perspectives on the bay’s future. Operation of the Salem and Hope Creek Nuclear Generating Station (construction started in 1968) in Lower Alloways Creek, New Jersey, did not go unchallenged. Studies in the 1980s documented the generating station’s role in Delaware Bay fish mortality. Environmentalism’s most conspicuous impact led to unprecedented emphasis on recreational uses of the Delaware Bay and the rise of ecotourism in the region. These priorities led to renewed interest in the Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge (1937) in Delaware and the creation of the Cape May National Wildlife Refuge (1989) in New Jersey. Complementing these federal measures was the active acquisition of shoreline areas by the states of New Jersey and Delaware for public use. In the twenty-first century, the bay’s present and future remained immersed in contested perspectives over how its human use and ecological health could best be sustained.

Michael J. Chiarappa is Professor of History at Quinnipiac University and co-editor (with Brian C. Black) of Nature’s Entrepot: Philadelphia’s Urban Sphere and Its Environmental Thresholds (Pittsburgh University Press, 2012). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge

- Cape May National Wildlife Refuge

- Delaware Bay & Estuary Basin (Delaware Watersheds)

- Oyster and Clam Diseases (Connecticut Department of Agriculture)

- Thomas Eakins (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- West Jersey Chapter - National Railway Historical Society

- Seed Oyster Production (New Jersey Aquaculture Innovation Center, Rutgers University)